|

|

|

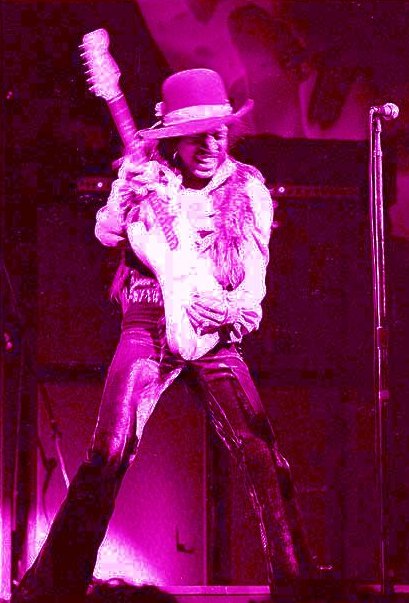

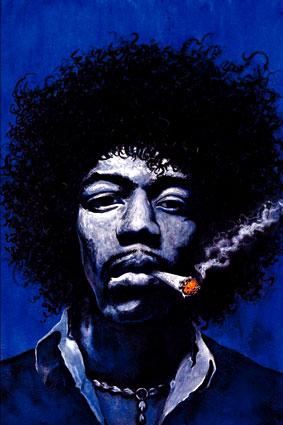

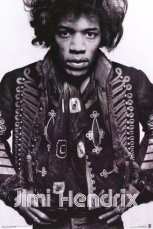

This is a tribute to Jimi Hendrix "Purple Haze, Jesus Saves"

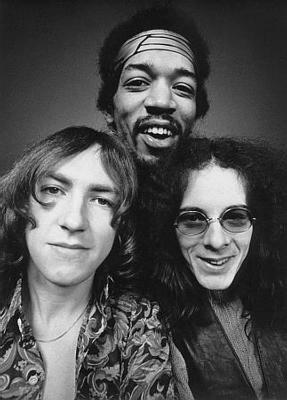

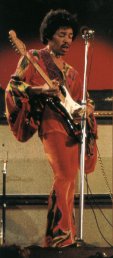

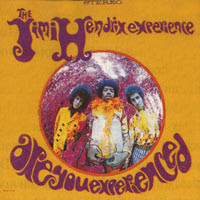

THE JIMI HENDRIX EXPERIENCE

THE JIMI HENDRIX EXPERIENCE

MITCH,JIMI,NOEL

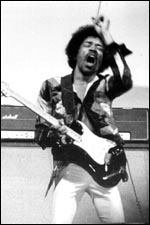

Jimi Hendrix expanded the range and vocabulary of

the electric guitar into areas no musician had ever ventured

before. Many would claim him to be the greatest guitarist

ever to pick up the instrument. At the very least his

creative drive, technical ability and painterly application

of such effects as wah-wah and distortion forever

transformed the sound of rock and roll. Hendrix helped usher

in the age of psychedelia with his 1967 debut, Are You

Experienced?, and the impact of his brief but meteoric

career on popular music continues to be felt.

More than any other musician, Jimi

Hendrix realized the fullest range of sound that

could be obtained from an amplified instrument. Many musical

currents came together in his playing. Free jazz, Delta

blues, acid rock, hardcore funk, and the songwriting of Bob

Dylan and the

Beatles all figured as influences. Yet the songs and

sounds generated by Hendrix were original, otherworldly and

virtually indescribable. In essence, Hendrix channeled the

music of the cosmos, anchoring it to the earthy beat of rock

and roll.

Hendrix was born Johnny Allen Hendrix on November 27th,

1942, in Seattle (his name was changed to James Marshall

Hendrix four years later). He acquired his first guitar at

age 16 and joined a group, the Rocking Kings, a year later.

Following an abortive stint in the Army, he hit the road

with a succession of club bands and as a backup musician for

such rhythm & blues artists as Little

Richard, the

Isley Brothers, Jackie

Wilson, the

Impressions and Sam

Cooke. In 1966 he was discovered by Chas Chandler,

the former Animals bassist, while performing at New York's

Cafe Wha? with his group, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames.

Chandler became Hendrix's manager and brought him to

England, where he absorbed the nascent psychedelic movement,

changed the spelling of his first name "Jimi" and formed a

trio with bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell.

The Jimi

Hendrix Experience recorded three landmark albums -

Are You Experienced?, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric

Ladyland - in a year and a half. Hendrix's theatrical,

incendiary performances at the Monterey Pop and Woodstock

festivals, including the ceremonial torching of his guitar

at Monterey, have become part of rock and roll legend. Under

extreme pressure due to a combination of nonstop work,

sudden celebrity and drug-taking, the trio broke up in early

1969. Hendrix commenced work on a projected double album and

debuted a new trio, Band of Gypsies, at the Fillmore East on

New Year's Eve 1969. Hendrix performed his last concert at

the Isle of Fehmarn, Germany on September 6, 1970 (though he

joined Eric Burdon and War on stage on September 16 at

Ronnie Scott's in London). On September 18, he died from

suffocation, having inhaled vomit due to barbiturate

intoxication.

In the wake of Hendrix's death, a flood of posthumous

albums - everything from old jams from his days as an R&B

journeyman to live recordings from his 1967-1970 prime to

previously unreleased or unfinished studio work - hit the

market. There have been an estimated 100 of them, including

Voodoo Soup (1995), an attempt to reconstruct First Ray of

the New Rising Sun - the album Hendrix was working on at the

time of his death - from tapes, notes, interviews and song

lists.

TIME LINE

November 27, 1942

Johnny Allen Hendrix is born at 10:15 a.m. at Seattle's King

County Hospital. His mother is Lucille Jeter, 17. His

father, James "Al" Hendrix, is in the U.S. Army, stationed

in Camp Rucker, Alabama.

November 27, 1942

Johnny Allen Hendrix is born at 10:15 a.m. at Seattle's King

County Hospital. His mother is Lucille Jeter, 17. His

father, James "Al" Hendrix, is in the U.S. Army, stationed

in Camp Rucker, Alabama.

December 25, 1945

Noel Redding was born.

September 11, 1946

Al Hendrix, now out of the service, changes his son's name

to James Marshall Hendrix. Al will take primary

responsibility for raising Jimi. "My dad was very strict and

taught me that I must respect my elders always. I couldn't

speak unless I was spoken to first by grown-ups, so I've

always been very quiet," Hendrix said of his childhood.

July 9, 1947

Mitch Mitchell was born.

September 1, 1957

Jimi Hendrix goes to see Elvis

Presley perform at Sicks Stadium.

February 2, 1958

Jimi Hendrix's mother dies.

SUMMER 1958

Jimi Hendrix's father buys him a second-hand acoustic

guitar. It costs five dollars. "Jimmy told me about it [the

guitar] and I said, ‘Okay,' and gave him the money. He

strummed away on that, working away all the time, any spare

time he had," said Al.

SUMMER 1959

Al Hendrix buys Jimi his first electric guitar, a Supro

Ozark 1560 S. Jimi joins the Rocking Kings. "My first gig

with them was at a National Guard armory. We earned like 35

cents apiece. We used to play stuff by people like the

Coasters," said Jimi.

SUMMER 1961

Jimi Hendrix enlists in the Army. Stationed at Fort Ord,

California, he writes home: "The Army's not too bad, so far.

. . . All, I mean, all my hair's cut off and I have to

shave. . . I won't be able to see you until two months from

now. . . we're going through basic training."

November 1, 1961

Now stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, Jimi Hendrix is

training to become a paratrooper. Meanwhile, he forms a

band, the King Kasuals, with a fellow soldier, Billy Cox.

July 2, 1962

After getting hurt during a jump, Jimi Hendrix gets an

honorable discharge from the Army. Over the next three

years, he will play numerous gigs and studio sessions with

such R&B stars as Little

Richard, the

Isley Brothers, Ike

and Tina Turner and Sam

Cooke.

April 1, 1965

Jimi Hendrix goes to New York with Little

Richard's band and takes a room at the Theresa

Hotel. Over the next several months, he will play with Little

Richard, King

Curtis, Joey Dee and the Starlighters and the

Isley Brothers. He also takes a job with a club band

called Curtis Knight and the Squires.

June 1, 1966

Jimi Hendrix forms a band called Jimmy James and the Blue

Flames, which also includes guitarist Randy California,

later of the group Spirit. They get a regular gig at Café

Wha? in Greenwich Village.

September 24, 1966

Jimi Hendrix and Chas Chandler, former bassist with the

Animals, fly from New York to London. There, Hendrix

will form a new band and Chandler will become the manager

of the

Jimi Hendrix Experience. En route, they decide to

change the guitarist's name from Jimmy to Jimi.

October 1, 1966

Hendrix jams with Cream at

the Regent Polytechnic College.

October 6, 1966

The Jimi Hendrix Experience holds its first rehearsal. The

group features Jimi on guitar, Mitch Mitchell, formerly of

Georgie Fame's Blue Flames, on drums, and Noel Redding on

bass. The following week, the Experience plays a four-day

French tour supporting Johnny Hallyday.

October 23, 1966

The Jimi Hendrix Experience records its first two songs,

"Hey Joe" and "Stone Free" at London's De Lane Lea Studios.

December 16, 1966

The Jimi Hendrix Experience release "Hey Joe" in England. By

February 1967, it reaches Number Four on the British charts.

The next single, "Purple Haze," reaches Number Three. The

group's debut album, Are You Experienced?, will remain near

the top of the charts through the summer of 1967.

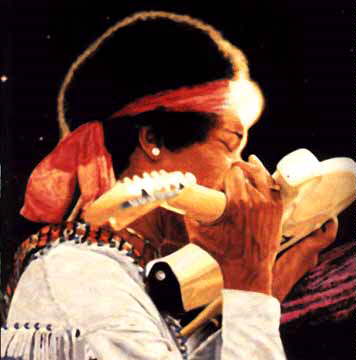

June 18, 1967

Jimi Hendrix performs at the Monterey International Pop

Festival. Brian Jones of the

Rolling Stones introduces him as "the most exciting

performer I've ever heard." At the end of his performance,

he burns his Fender Stratocaster. "The time I burned my

guitar it was like a sacrifice," Jimi said. "You sacrifice

the things you love. I love my guitar. I'd just finished

painting it that day and was really into it." Literally

overnight, the

Jimi Hendrix Experience become one of the most

popular acts in rock music.

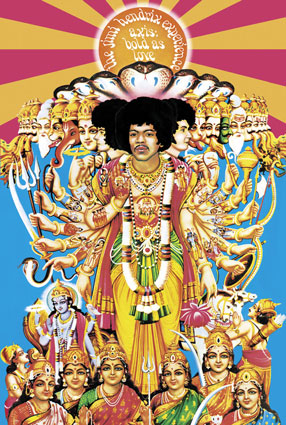

December 1, 1967

The Jimi Hendrix Experience releases 'Axis: Bold as Love'.

The album, which is released in the U.S. on January 15,

includes such songs as "Little Wing," "If Six Was Nine,"

"Castles Made of Sand" and "Spanish Castle Magic."

February 1, 1968

The Experience embarks on a major U.S. tour. The first show

is at the Fillmore, in San Francisco. On February 12, Jimi

Hendrix returns to Seattle for a show at the Center Arena.

Jimi's family is seated in the front row.

October 18, 1968

Jimi Hendrix's version of Bob

Dylan's "All Along the Watchtower" is released.

"Before I came to England, I was digging a lot of the

things Bob

Dylan was doing," Jimi said. "He is giving me

inspiration."

October 25, 1968

Electric Ladyland, a double album recorded in the

U.S. and England, is released. It becomes Hendrix's first

Number One album in the U.S. and includes such tracks as

"Voodoo Chile," "Crosstown Traffic" and "All Along the

Watchtower."

February 24, 1969

The Jimi Hendrix Experience plays its last British

performance at London's Royal Albert Hall.

June 29, 1969

The Jimi Hendrix Experience plays the final date on its last

American tour at the Denver Pop Festival. At the height of

its popularity, the group breaks up.

AUGUST 15-17, 1969

The year 1969 was the year of the rock festival. The largest

was the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, held on the weekend of

August 15-17 in the tiny town of Bethel, in upstate New

York. An estimated crowd of 450,000 attended the event,

which featured everyone from Jimi Hendrix and Joe Cocker, to

Arlo Guthrie, the Jefferson

Airplane, the

Who, Janis

Joplin, Sly

and the Family Stone, Ravi Shankar and Country Joe

McDonald. If Woodstock marked the apex of the hippie

movement in America, the

Rolling Stones' free concert in Hyde Park did the

same for England. Held on July 5, the show drew nearly

300,000 people, the largest gathering in England since V-E

Day.

August 18, 1969

Hendrix debuts a new band, Gypsy Sun and Rainbows, at the

Woodstock music festival in New York State. The group

includes old friend Billy Cox on bass, Mitch Mitchell on

drums, Larry Lee on rhythm guitar and Juma Sultan and Jerry

Velez on percussion. He takes the stage at 7:30 in the

morning, and his version of "The Star Spangled Banner"

becomes the highlight of the festival.

DECEMBER 31, 1969 - JANUARY 1, 1970

Band of Gypsys – a trio with Hendrix, Cox and drummer Buddy

Miles – plays Bill

Graham's Fillmore East in New York. Graham calls the

shows "the most brilliant, emotional display of virtuosic

electric guitar playing I have ever heard."

April 28, 1970

Jimi Hendrix and the

Band of Gypsies "The Cry of Love" tour begins at the

Forum in Los Angeles. Mitch Mitchell is back on drums.

SUMMER 1970

The Cry of Love with the

Band of Gypsies tour continues, with shows at

Berkeley, Rainbow Bridge in Hawaii and the Atlanta Pop

Festival. The group begins work on a new double album,

'First Rays of the New Rising Sun'. Though some of the

tracks are released as The Cry of Love, the album

does not get its full release until 1997.

August 25, 1970

A grand opening party is held at Electric Lady Studios,

which Jimi has designed for himself in New York.

August 30, 1970

Hendrix performs at the Isle of Wight Festival in England.

September 6, 1970

Hendrix, Cox and Mitchell play the Love and Peace Festival

in Puttgarden, Germany. Hendrix then returns to London.

September 16, 1970

Jimi Hendrix jams with Eric Burdon and War at Ronnie Scott's

Club.

September 18, 1970

Jimi Hendrix dies in his sleep at the Samarkand Hotel in

London. He was 27.

Jimi Hendrix

Band of Gypsys:

09/18/1970

The spiritual bishop of rock and roll, the man who united the streams of

R&B, blues, funk and rock into such a fantastic animal, died today.

Jimi leaves in his wake his final record. Released just five months

ago, Band of Gypsys documents one of Jimi's classic moments on stage at

the Fillmore East in New York City on New Year's Eve, 1970. Though it

serves now as a requiem, the album began its life as the promise of

birth. Jimi had grown tired of his poppier arrangements and was ready to

thrust himself into a new experimental stage with his two-man band of

Buddy Miles and Billy Cox abreast. The Fillmore East performances

suggested that Jimi was moving into new territories. He had established a

platinum reputation, and the only thing left to hold him back was his

own imagination. Band of Gypsys shows us how far that imagination may

have gone had it not been so hastily ripped from our presence.

Band of Gypsys is a tremendously organic, moody creature to invite into

the ears. Running the gamut from intense, climactic moments of intensity

to distorted, minimal suspense, Gypsys is a stunning departure from

Jimi's more wry, grittier material like "Hey Joe" or "Highway Chile." As

if the social tumult of racial strife and an unwilling war had been

swallowed by Jimi's guitar and released again by his fingertips, Gypsys'

atmosphere is introspective, regretful, frustrated, and angry-- the

cries of protest from a man whose words were his music.

Perhaps the most fantastic aspect of this record is the crowd. Though

the tempo often changes to silence excepting only a lightly tapped

hi-hat or tremblingly picked guitar, the silence in the rapt Fillmore

East captures the power of the performance. If silence is golden, the

crowd has paid Jimi, Buddy and Billy the highest ransom to express

themselves to the fullest, and the favor is returned. Remember him, my

brothers and sisters. Amen.

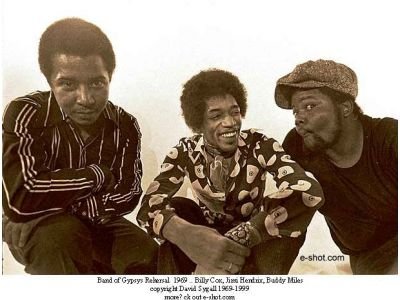

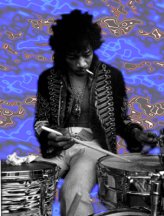

Jimi Hendrix at Band of Gypsys, 1969

Jimi Hendrix at Band of Gypsys rehearsal with Buddy Miles on drums, NYC, 1969

|

|

|

JIMI'S FUNERAL

Jimi's grave Greenwood Memorial Park, Renton, Washington USA

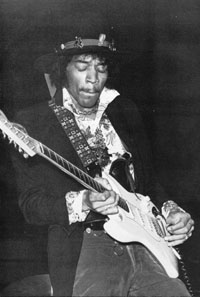

The Jimi Hendrix Experience on stage at the Fillmore East, May, 1968

Bassist for Jimi Hendrix Experience dies MAY/11/2003

DUBLIN, Ireland (AP) — Noel Redding, bass player for the legendary

Jimi Hendrix Experience from its formation in 1966 through its

dissolution three years later, has died. He was 57. Redding was found

dead Monday at his home in the town of Clonakilty in southern Ireland,

his manager, Ian Grant, said Tuesday. An autopsy was planned to

determine the cause of death.

Noel was an extremely gentle and gracious soul. He had a kind of

chivalry and nobility about him and he was kind to everyone bar none,

people and animals alike," said Deborah McNaughton, his longtime

partner.

Chas Chandler, a former bassist for The Animals who became a rock

manager, recruited Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell to form the

Experience with Hendrix in England.

The band produced three groundbreaking albums of psychedelic rock —Are

You Experienced?, Axis: Bold as Love and Electric Ladyland. Its hits

included Purple Haze, Hey Joe and Foxey Lady.

The group broke up in 1969 before the famed Woodstock appearance by

Hendrix, who died the next year from choking on his vomit after taking

sleeping pills and drinking wine.

Redding wrote two Experience songs: She's So Fine and Little Miss

Strange.

Born Dec. 25, 1945, in the English Channel port city of Folkestone,

Redding played with the Modern Jazz Group and the Loving Kind before

joining the Experience.

He has said that his greatest achievement was playing the 1967 Monterey

Pop Festival, where the Experience made its American debut and Hendrix

lit his guitar on fire, and the band's 1992 induction into the Rock and

Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland.

After the breakup of the Experience, Redding formed his own band, Fat

Mattress, which released a 1969 album of the same name, followed by Fat

Mattress 2 in 1970. Both were re-released as a set in 2000.

Later, he formed the Noel Redding Band, which recorded Clonakilty

Cowboys in 1975 and Blowin' in 1976. Other recordings included On Tour

in 2001 and last year's Live From Bunkr-Prague.

In 1990, Redding and Mitchell each published books about their

experiences.

"Jimi's death was the most lucrative act of his sad career," Redding

wrote in Are You Experienced? in which he alleged that the Hendrix

estate owed him money.

In February, Redding threatened to sue Experience Hendrix, the company

that manages the Hendrix catalogue, for up to $5 million in lost

earnings. The estate rejected the claim.

On Tuesday, the Experience Hendrix Web site mourned Redding's death,

saying, "His contributions to the Jimi Hendrix Experience shall never be

forgotten."

Redding played most Friday nights for the last 20 years at De Barra, a

local pub, Grant said, often with his friends John Coughlin from Status

Quo and Eric Bell of Thin Lizzy.

Redding had no children. A funeral was planned for the weekend in

Clonakilty.

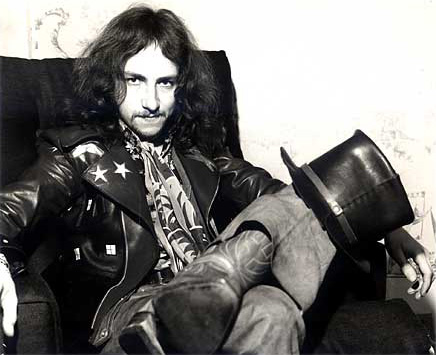

THE DRUMMER MITCH MITCHELL

John Ronald "Mitch" Mitchell (9 July 1947 – 12 November 2008) was an English drummer, best known for his work in The Jimi Hendrix Experience

Mitch Mitchell...

A child actor, Mitch was largely self taught, though he received some

lessons when he worked in Jim Marshall’s (the Amp man) music store.

Mitch did some free lance work before settling in with Georgie Fame and

the Blue Fames. One of the great UK jazz inflected R&B bands. After

18 months George fired the whole band as management wanted a change in

direction. The next day Mitch got a call from Chas Chandler to come and

try out with this American he was managing. Mitch was invited to join

for two weeks work

touring France. One of the great musical synergies was born.

Jimi Hendrix has a magnificent rhythmic drive, his playing sets the

groove. He also has a strong idea what the bass player is to play.

Indeed he is a pretty good bass player himself as on several tracks he

replaced Noel Redding and recorded the bass himself ("All Along the

Watchtower",

"1984…"). With Jimi setting the groove and the bass player holding it

and following his lead, the drummer had great opportunity to fill and

interact. Jimi and Mitch are closer to Townshend and Moon, then with

Cream (Baker had two lead guitarists!).

Mitch is a jazz influenced player, especially Elvin Jones but also Max

Roach and Joe Morello. He uses the underhand or military grip switching

to matched for tom work. He used a variety of kits: first Premier with

20" bass & 14x 8" top tom, then a Ludwig Silver Sparkle in the

classic jazz setup: 22" bass, 13x9" top, 14x14" & 16x16" floor,

Ludwig Supra-phonic snare. Cymbals varied but typically: 15" Hi-hat, 20"

ride, 20" & 22" crash and later a 22" or 24" riveted ride. In 1969

he moved to a Ludwig double bass kit with 24" bass drums and additional

12x8" top tom, then the same setup on Gretsch (possibly Ludwig

sponsorship in Europe and Gretsch in USA). The double kit didn't change

his style, it just added some tonal variety. Sticks were medium/heavy

and he played seated low in a hunched position.

Mitch plays in the Elvin Jones explosive style with fast snare and

cymbal riding coupled with more basic rock triplet bass patterns and big

bombs. In line with jazz drumming he played within the

snare/hi-hat/ride cymbal/bass drum arc with the toms as variations. His

hi-hat and cymbal work is of the highest order and he used brushes on

occasions. He is criticised as a busy drummer which is grossly

overstating the case. More restrained drumming may have been more

appropriate on a few tracks (that’s Mitch’s opinion). I really can’t

describe them as flawed, just that it could have been done differently

and that doesn’t mean better!

The thing that Mitch had was incredible stamina especially in the studio

as Hendrix endlessly worked though songs. He always responded to

Hendrix’s variations and worked from his arrangement. Mitch never

defined his arrangement within the song. Live was the same, as it was

need to follow Hendrix’s improvisations and also fill in those gaps,

especially when Hendrix did his stage act. It was behind these that

Mitch took his solo over a droning bass line, usually at an exciting

high tempo. He was a fast drummer - lightning at times and surprisingly

loud for his diminutive statue. But as a true soloist he could not

retain momentum - the solo on "Voodoo Child" looses momentum

surprisingly quickly. This is a result of the lack of thorough formal

training and the techniques that it provides to build a coherent solo - a

limitation of no relevance in this band.

Mitch’s critical asset was his explosive, intuitive responsiveness to

Jimi. He could lay down a strong, light groove but then instantly react

as Hendrix shifted gears or moved off in another direction. His style is

in stark contrast to Buddy Miles who lays down a relentless groove

which, when combined with the solid groove bass playing of Billy Cox,

stultified Hendrix.

Mitch’s return freed up Hendrix and Billy Cox as well. I really cannot

conceive of Baker playing this sort of role - his personal rhythmic

impetus would also have impeded Hendrix but not as greatly as Miles.

After Jimi died, Mitch languished in some ordinary projects. The one

that had the greatest potential was the Jack Bruce/Larry Coryell/Mitch

Mitchell/Michael Mandell jazz/rock fusion band. The available bootlegs

show Mitch playing in a jazzier style with some Bakerish inflections

with the tom fills. What I find most interesting is that the rhythmic

drive is coming from Jack, allowing Mitch to fill, reinforce and explode

but in a controlled way. That was a good band that should have gone on

but Jack got the irresistible call to join the Tony Williams Lifetime.

The third of the great British Rock drummers of the ‘60s, with a very

different style and technique. His legacy is an indispensible part of

that of Jimi Hendrix’s …’nough said.

Greatest moments: "Manic Depression", "Fire", "Crosstown Traffic" (the

groove), "Hey Baby (New Rising Sun)"and the BBC sessions.

Historical Footnote: Ginger and Mitch were not rivals, in fact they were

friendly members of the drummers club. On the night that Jimi died,

they had picked up Sly Stone from London airport and were looking for

Jimi to participate in a jam.

BUDDY MILES DRUMMER BAND OF GYPSYS.

George Allen Miles, Jr. (September 5, 1947 – February 26, 2008), known as Buddy Miles,

Miles has come a long way since his first professional gig, when at the

age of twelve he began playing drums in his father's jazz combo in

Omaha, Nebraska. It was only a matter of time before his inimitable

bottom-heavy style attracted the attention of the multitudinous R&B

and doo-wop groups who were touring the chitlin' circuit and,

eventually, the teenaged Miles landed a seat as part of Wilson Pickett's

live revue.

In 1967, while performing with Pickett, he was approached by Michael

Bloomfield and Barry Goldberg and asked to join a new psychedelic rock

band called The Electric Flag. With Miles on drums, the Flag recorded

one high-voltage slab of vinyl before parting ways in 1968. Up from the

skies came the freshly-formed Buddy Miles Express and a renewed

friendship with Jimi Hendrix, with whom Miles had been running as early

as June of 1967, when the two played the Monterey Pop Festival.

Hendrix's archetypal and apocalyptic Electric Ladyland marked the

beginning of their fruitful collaboration in the studio, with Miles

laying down a solid backbeat dripping with the blues for "Rainy Day" and

"Still Raining." Hendrix would return the favor by writing the

beautifully envisioned liner notes for BME's EXPRESSWAY TO YOUR SKULL

and producing tracks for the follow-up ELECTRIC CHURCH in 1969.

After the breakup of the Jimi Hendrix Experience in late 1969, Hendrix

recruited Miles for what would be one of the lasting musical statements

of both their careers. Over the protests of his management, who feared

the repercussions of adopting a so-called "Black Power" stance in his

music, Jimi formed the Band of Gypsys with Billy Cox on bass and Miles

on drums and backing vocals. Arguably the first true "black rock" band,

the Gypsys debuted at Bill Graham's Fillmore East on New Year's Eve 1970

and opened their historic second set with the Hendrix classic "Machine

Gun." Writer David Henderson described Miles in action in 'Scuse Me

While I Kiss the Sky, the definitive Hendrix biography:

"Buddy Miles pauses, eyes closed, like a Buddha within a silver metal

bubba flowing outward, his snare shots wide and strong. He beats into

the depths of a groove, the snare shots ratatatting stronger and

stronger. Miles captures and entrances you with his repetition. The

intensity of his shots ring out on par with Jimi's guitar."

The Fillmore set formed the basis of the Band of Gypsys live album,

which featured two tracks written by Miles "We Gotta Live Together" and

the seminal "Them Changes," which has since become the signature song of

the Express. Ironically, although Band Of Gypsys was in many ways a

breakthrough for Hendrix, the group dissolved scarcely two months later

for reasons that remain mysterious even to this day. Miles-o-philes can

dig other Gypsys cuts on the obscure Hendrix collection, "Loose Ends,"

an invaluable document of rehearsals and outtakes that features the

extended funk workout "Burning Desire."

"Twenty years ago, before Living Colour and the Black Rock Coalition,

there was Buddy Miles and his visceral Hard Soul....Hell And Back may be

an apt description of where he's been, but Buddy uses it all as

inspiration for this diverse record of behind the beat fatback funk and

hard R&B jamming." -- MODERN DRUMMER

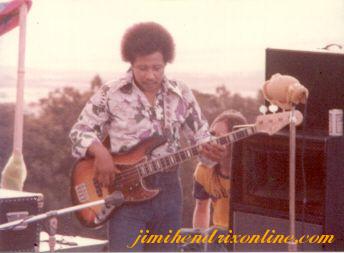

BILLY COX BASS BAND OF GYPSYS:

William "Billy" Cox (born October 18, 1941) is an American bassist, best known for performing with Jimi Hendrix.

As of November 12, 2008, he is the only surviving member of both The Jimi Hendrix Experience and the Band Of Gypsys

Billy Cox really needs no introduction. Jimi's close friend since they

met in the Army at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, Billy was the bass player in

the legendary Band of Gypsys and toured and recorded with Jimi for the

last year and a half of his life.Billy Cox

Born in West Virginia, DOB unknown.

Billy Cox holds a unique position in the life of Jimi Hendrix. Cox knew

and played in bands with Hendrix before he became famous, and after.

Billy first met Hendrix in the early part of the Sixties, when they were

both in the Army. Cox, a bass player, teamed with Hendrix in an R &

B band called the King Casuals.

They re-united musically in 1969, when Hendrix called on Cox to play

bass in the experimental funk band the Band of Gypsys.

Billy Cox played at Woodstock with Hendrix's Gypsy Sun and Rainbows, and

toured with Hendrix (with Mitch Mitchell on drums) for most of 1970 on

the Cry of Love tour.

Cox lives in Nashville TN. where he remains active in music, and acts as

an ambassador for Jimi Hendrix, his music and philosophy.

It´s like trying to get out of ROOM FULL OF MIRRORS

Despite everything written about Jimi Hendrix since his death, vital

questions remain unanswered. The Coroner's "Open Verdict" could stand as

a final

comment on his life. In the light of facts unearthed since 1970 we

present a detailed reconstruction of his last eighteen months, and his

last hours.

THE JIMI Hendrix Experience, put together by Chas Chandler in 1966, was

moribund only two years later. The Experience had gone up like a rocket,

trailing clouds of glory, sensationalism and instant success. By 1968

it had burned itself out. A handful of brilliant singles, two

crackerjack albums - the first an explosive flash, the second a slow

burn - and gigs of ferocious visual and aural pyrotechnics were its

legacy.

But Hendrix wanted to be something more than the super hippy stud guitar

hero of his media image. He felt constrained by the limitations of the

three piece - and personality problems with Noel Redding didn't help.

During their tour of Sweden in January '68 Hendrix had been incarcerated

overnight after wrecking a hotel room, following a row with Redding.

(The subsequent fine cost him the proceeds from the tour.) And neither

did his difficulties with Mike Jeffrey, Chandler's partner, who wanted

the success formula to continue.

The third album, the double 'Electric Ladyland,' recorded during 68, may

have been for Hendrix a step in the right direction with extended

'unconventional' tracks and a bunch of guest musicians contributing. But

for Mike Jeffrey it was bad news on at least two counts: it was a

double, with therefore a lower "sales profile" (the controversial nudes

cover didn't help either) and musically it was a (large) step away from

"Purple Haze" and "Are You Experienced?" It was also very uneconomically

recorded - over an extended period with much loose jamming and "wasted"

studio time.

But it wasn't only the money-minded Jeffrey who was unhappy with the way

Hendrix was going. Chas Chandler was concerned about Hendrix's

behaviour, which was becoming somewhat unpredictable. In addition, he

was eased out (or quit) as producer during the recording of 'Electric

Ladyland')and in frustration sold out his 50% interest in Hendrix to

Jeffrey.

In November '68 the Experience broke up. They played two farewell gigs

at the Albert Hall in February '69. Chapter One was ended. The only

remaining chapter was to be the epilogue.

A timetable of the last two years of Hendrix' life makes horrifying

reading. A catalogue of wrong moves, false starts, accidents,

misfortunes, contradictions, unanswered questions and downright

disasters, accelerating and intertwining more and more tightly as they

approached the final week, that pose many questions about the reasons

for and events behind Hendrix' death.

IN FEBRUARY '69, Hendrix left for the States. Jeffrey brought Chas back

in again to look after things while he was in America. Hendrix phoned

Chas up and asked him to come back as his manager. Chas refused.

In New York, Hendrix was recording at the Record Plant with Buddy Miles

on drums and Billy Cox on bass, doing a double album which was intended

to be his final statement as a 'pop star.' He desperately wanted to move

on from the rut he found himself in. Alan Douglas, a friend of his, and

who was producing John McLaughlin's 'Devotion' album in the same

building, was asked by Hendrix to be his Foducer. Douglas entered into a

verbal agreement with Jeffrey and for the moment everything was fine.

Hendrix jammed with McLaughlin and organist Larry Young (also on

'Devotion,' who had been with McLaughlin in Lifetime) and other rock

notables.

***

Then in May at Toronto International Airport arriving for a gig, Hendrix

was busted for possession of heroin. He was released on bail of $10,000

but the case was to hang over him till December.

During the Summer and Autumn, Hendrix was mainly living at a house in

Liberty in upstate New York with an 'electric family' of musicians

including Mitch Mitchell, conga player Juma Lewis and avant-garde

pianist Michael Ephron. Naturally, none of this was desirable to his

commerce consciousness management and Hendrix had to escape to Algeria

and Morocco on holiday a couple of times to avoid the presssure.

By June, he was playing again with Billy Cox and Mitch Mitchell, back

with the reassurance of familiar faces. In July they played Newport and

in August, Woodstock. ("You can leave if you want to. We're just jamming

that's all." said an obviously not overhappy Hendrix.) Also in August

was a disastrous gig in Denver which was broken up by tear gas lobbing

riot police.

In December, Hendrix' old manager, Ed Chalpin won his suit against him.

Hendrix had signed with Chaplin when he was in Curtis Knight's band and

thus had renewed on this contract when he left for Britain with

Chandler. Merely for having Hendrix' name on a piece of paper, Chaplin

was given the US rights to one album ('Band Of Gypsys' which came out on

Capitol in America); a percentage or Hendrix' earnings, past and

present; and $ 1 million upfront.

Also in December, on a happier note, Hendrix was acquitted of the

Canadian drugs charge. The defence had been that he did not know about

the heroin which had been put in his bag on his departure by a girl who

said it would be good for the cold from which he was suffering and that

he hadn't opened the package.

John Swenson in the American magazine Crawdaddy however quotes an

anonymous New York musician who says that Hendrix was afraid that the

drug was a plant and that the bust was arranged by Jeffrey to keep him

dependent on Jeffrey at a time when he was obviously slipping our of his

domination. There is however, a strong counter-claim, again anonymous,

that the dope was neither a plant nor an unfortunate present. (Although

the coroner found no needle marks whatsoever on Hendrix' body, it is

accepted that Hendrix did snort heroin. Chris Welch in his biography

'Hendrix' quotes PR man Robin Turner on this.)

On New Year's Eve the all-black Band of Gypsys (Hendrix, Miles and Cox)

debuted at Fillmore East, described by Bill Graham as some of the most

amazing music he'd ever heard but regarded typically less

enthusiastically by Hendrix. (This gig was recorded for the 'Band Of

Gypsys' album that Chalpin got).

At the end of January 1970, Band of Gypsys played their second concert

at a Peace Rally in Madison Square Garden in Front of 19,000 people.

During the second number Hendrix stopped, announced "I'm sorry but we

just can't get it together" and walked off. End of Band of Gypsys.

In May the reformation of Experience was announced. At the end of May

Hendrix played a concert at Berkeley Community Theatre - with Billy Cox

and Mitch Mitchell. No Experience reunion.

Through '69 and early '70, Hendrix was mainly in the studio and also

working towards his own 'dream' studio, Electric Lady, where he could

make his own music in his own environment. But again there were the

inevitable difficulties.

Hendrix found, to his amazement, that he didn't have enough money to

finance the studio himself and that he had to borrow from Warner Bros.

(his US record company). Biographer Curtis Knight quotes Hendrix: "I

know I have been spending a lot of money lately but I have also been

making a lot of money and I was shocked to learn what my financial

situation is. I had a lot of faith in the people that were handling my

affairs - I trusted them. But there are definitely going to be some

changes made...I am going to get in touch with my lawyer in America and

straighten everything out. The vultures have lived off me long enough."

In June, Hendrix was in Hawaii for the 'Rainbow Bridge' film, although

the soundtrack was recorded at Electric Lady at the beginning of.July.

At the end of July he played his last gig in the States, in Seattle, his

home town. Another catastrophe, with Hendrix reduced to shouting "Fuck

you! Fuck you!" at the audience.

On August 25 there was the opening party for Electric Lady with everyone

getting totally ripped. The next morning, not having slept, Hendrix

flew out for Britain and the Isle of Wight Festival. At 3 a.m. on the

cold, damp morning of 27 he came on to play his last British

performance.

It was followed almost immediately by a European tour and by preliminary

meetings to settle the Chalpin / Jeffrey contract dispute in Britain.

The tour got to Holland where the last date on September 14 in Rotterdam

was cancelled. Billy Cox had had a nervous breakdown and was flown back

to the States. Hendrix returned to London.

On Tuesday 15, Curtis Knight reports a wild party lasting all day in

which Hendrix was a participant. Knight quotes Lorraine James, a 21 year

old shop assistant who saw Hendrix that day: "He was on the coin box in

the building for hours, trying to contact people. One minute he was on

top of the world and the next minute he was moaning about his backers

and his financial affairs."

The evening of Wednesday 16 seems to have been a busy one for Hendrix.

He showed up at Ronnie Scott's club to jam rather badly with Eric Burdon

and War. He also phoned Chas Chandler to ask him to be his manager

again. And also talked with Alan Douglas "all night" trying to persuade

him to become his manager. Douglas finally agreed and left for the

States the next morning. Douglas also says that for the previous week

Hendrix was "running around talking to people and doing that thing."

Chandler has said that for four weeks previous to his death Hendrix had

asked "a dozen people to produce for him" too.

"I'm not really sure about his

death . . .I don't know if it was

an accident or suicide or murder."

The next day, Thursday 17, Hendrix cal1ed New York and set up

appointments for Douglas to see his attorney. He also called Chas about

the design for his new album cover - and he was due to leave for New

York himself to pick up the album tapes. There was a meeting scheduled

too with Chalpin but Hendrix didn't turn up.

That much perhaps is fairly certain, though the closer we appoach to his

death the less definite things become. The last few hours become

somewhat confused and contradictory. firstly, Noel Redding is quoted in

Chris Welch's book that he thinks Hendrix dropped some acid sometime

during the evening. No one else mentions it and Redding doesn't say why

he thinks so.

***

It's necessary now to introduce three of the women in Hendrix' life:

Jeannette Jacobs, Devon Wilson (who introduced Hendrix to Alan Douglas)

and Monika Danneman.

Jeannette Jacobs says in Chris Welch's book that "just before he died"

Monika showed her a ring she had been given by Hendrix, saying that she

and he were getting married. "I fell for it unfortunately," says Jacobs,

"and left the country. Jimi said, "please wait." But having heard this

from the girl right in front of me, I didn't have a leg to stand on. The

night before he died somebody told him I had gone away. In the morning

he was found dead. I just think it had to happen." Apart from the fact

that Hendrix wasn't exactly "found dead," that's straightforward enough

on its own terms. Make of it what you will.

The Wilson / Danneman situation is more confusing. Accoring to one

account, Hendrix went to see Devon Wilson before he went back with / to

Monika at the Samarkand Hotel. But John Swenson in Crawdaddy quotes from

Danneman's unpublished book where she says that Monika drove Hendrix to

Devon's where he only stayed a few minutes.

At any rate, according to the standard Danneman account he was with her

in the hotel by 8.30 p.m. where she made him a meal, during which they

drank some white wine. Hendrix washed his hair and had a bath then they

sat and talked and listened to music.

At 1.30 a.m., Hendrix called Chas Chandler's office and left a message

"I need help bad, man." (Danneman doesn't mention this - and Knight says

it happened the night of the party two days previously.)

At 1.45 a.m. Hendrix told her he had to go to some people's flat. "They

were not his friends and he did not like them but he wanted to show them

he could cope. He told me he did not want me to go with him so I

dropped him off there and picked him up an hour later, just after

three." Hendrix apparently smoked some grass there. When they returned

home, Monika made him a tunafish sandwich.

And now another divergence. According to her book, at 6 a.m. Hendrix

complains that something is wrong - that Devon had "slipped him an OD."

But apparently totally unconcerned, he takes a handful of sleeping

tablets, urges her not to commit suicide and talks until she falls

asleep.

The other account makes no mention of this. At 6.45 a.m., she takes a

sleeping tablet and they talk until she falls asleep around 7.00.

Sometime after that Hendrix apparently takes nine Vesperax sleeping

pills. (The normal dose is a half and Hendrix apparently normally took

two).

Sometime soon after 10.00 a.m. Chas calls Hendrix having listened to his

answering service as soon as he came in. "Call me a bit later, man,"

says Hendrix.

At 10.20 a.m. Monika wakes. Hendrix is asleep and she goes out for

cigarettes. When she returns at approximately 10.30 Hendrix is still

asleep but he has been sick. She calls Eric Burdon who advises her to

call an ambulance. After some thought in case Hendrix is perfectly all

right and will wake up annoyed in hospital, she phones for an ambulance

at, say, 11.00.

The ambulance arrives about 11.20. The ambulancemen instead of laying him down, sit him up with his head unsupported.

At 11.45 a.m., Jimi Hendrix is found to be dead on arrival at St. Mary Abbot's Hospital, having choked on his own vomit.

***

ON SEPTEMBER 21, Eric Burdon appears on BBC-TV talking of a 'suicide

note,' that "Jimi made his exit when he wanted to" and that "he used a

drug to phase himself out of this life and go someplace else."

On 23 the inquest at Westminster is adjourned by Coroner Dr Gavin Thurston awaiting the pathologist's report.

On 25, Hendrix was due to have completed preliminary meetings with the

brilliant jazz arranger and orchestra leader Gil Evans for them to

record Hendrix with an orchestra.

On 28 the pathologist Prof. Donald Teale reports that death was due to

"inhalation of vomit due to barbiturate intoxication." An open verdict

is declared. In his summing up, the coroner says: "The question why

Hendrix took so many sleeping pills cannot be safely answered."

Hendrix' body was flown back to Seattle where it was buried on Oct.1.

***

THE QUESTION of the pills is far from being the only one that cannot be safely answered about the end of Jimi Hendrix' life.

The seemingly inexorable gathering momentum of the last few days is

awful enough in itself - and those events pose many questions that will

never be answered.

Why did supposedly competent ambulancemen act contrary to any training

they could have had and handle Hendrix in the worst possible way? Who

were the people he went to see that night? Just dealers - or someone

else? ("He wanted to show them he could cop": does that refer to dope -

or what?) Although the 'OD' story seems fanciful, coupled with the

Redding quote, Hendrix would seem to have ingested something that night

apart from wine, grass, a tunafish sandwich and nine Vesperax.

The whole of the Redding quote appears in Chris Welch's book: "I'm not

really sure about his death. I think the night before he dropped some

acid. I don't know if it was an accident or suicide or murder. I was in

the States and I heard that Bill Cox freaked. He was convinced somebody

was trying to kill him."

Was Cox suffering from paranoia following his nervous breakdown? Or was

someone trying to kill him? Did someone try to kill Jimi Hendrix?

Or was it really just a tragic accident? That, as Germaine Greer

suggested, Hendrix just wanted to go to sleep for a long time, for a

couple of days, so that no one coud reach him, so that he wouldn't have

any problems to worry about.

To understand the full nature of these problems we must go back even before Chandler saw and met Hendrix in New York in 1966.

***

Jeffrey was involved with Chandler in the first place as manager of the

Animals. A holding company, Yameta, was set up in the Bahamas by

Jeffrey, Chandler, Eric Burdon and one Leon Dicker to keep their

earnings out of the British taxman's hands. But Rolling Stone in a

feature about Hendrix' funeral reports that Burdon accused Jeffrey of

cheating him out of his money in those Animal days. Jeffrey replied that

Yameta had been unable to account for the missing money and that he had

lost out as well. He offered to sue Yameta jointly with Burdon but

Burdon went ahead and sued Jeffrey in a New York court.

Moving forward to the early days of Experience, we can find several

instances of personal and financial mismanagement by Jeffrey. Chandler

had had to bring Jeffrey in as a financial partner because he, Chas, had

very little money indeed, hocking his guitars one by one to provide the

upfront cash needed to launch Hendrix. They had half shares in Hendrix

so that, according to Noel Redding, Hendrix got 50% of the earnings

Mitch and he got 12.5% each, and Chandler and Jeffrey got 12.5% each.

But Chandler complains in Welch's book that when he brought Hendrix to

London, Jeffrey was nowhere to be found until following April. Again in

Welch's book, Noel Redding says that when, in the Spring of '67, the

Experience were getting £1,000 a night he was on £15 a week. He had to

resign three times before it went up to £200.

And it wasn't just Redding. When in New York on his way to Monterey,

Hendrix met up again with Curtis Knight and Chalpin. Hendrix had to

borrow money from Chalpin because he didn't have any cash - and when he

asked Jeffrey it was refused. Curtis Knight reports that Hendrix didn't

know how much he had in the bank or even which bank his money was in.

(Having lent him the money, Chalpin then informed Hendrix that he would

be suing him about his broken contract.)

After the total success of the Experience at Monterey, all that Jeffrey

was concerned about was that they'd broken a 150 dollar mikestand.

Then there was the Monkees tour fiasco. Jeffrey set up a tour with the

Monkees which he thought was a great deal. The Monkees were happening at

that time and that was all that mattered to Jeffrey - the complete

mismatch didn't enter his head. When he told Chandler on the phone, Chas

hung up.

Chandler apparently manged to pull the Experience out of the tour with a

concocted story about the Daughters of the American Revolution shocked

and enraged by 'wild man' Hendrix. When he told Jeffrey, it was

Jeffrey's turn to be angry and he disappeared again - to Majorca for

seven months.

But at least Hendrix seemed aware of what was going on - perhaps as a

result of the Chalpin / Knight embarrassment. A letter was sent to

Warner Bros. in August '68 signed by Hendrix, Redding and Mitchell

stating that no money was to be paid to Yameta. Apparently it was not

obeyed.

Jumping forward to the Band of Gypsys. Again in Rolling Stone there is a

report of accusations by Buddy Miles that Jeffrey was cheating him -

with the implication that Hendrix was being ripped off too. Jeffrey

however produced papers to 'disprove' this. Jeffrey said that the

Hendrix earnings went straight to a New York accountant. He again

produced papers to prove that he didn't get any money until the

accountant paid him the standard manager's fee out of Hendrix's

earnings. But referring back to Noel Redding, neither 12.5% nor the 25%

he was now getting with Chandler's share can be described as "standard

manager's fee."

Then there were the musical differences. Jeffrey was obviously unhappy

with the way Hendrix' music was going. Although he had agreed to have

Alan Douglas acting as producer initially he soon had second thoughts.

Says Douglas: "Michael became afraid of me, became afraid of Buddy

Miles. Me and Buddy were pulling Jimi into another direction. Michael

got scared that we were pulling him away from him‹which was happening...

so that Michael made problems for Jimi all the time."

"Every time that we started up something that he wanted to do Michael

would superimpose his own shit on it. Like, if we were going to do a

date and record certain kind of tunes, Michael found a gig that Jimi had

to do that day or Mitch Mitchell was in town and he would pull Mitch

into the studio. And Jimi loved Mitch so much he would cancel everything

else so that he wouldn't hurt Mitch's feelings."

Though to be fair to Jeffrey, Chandler didn't approve of Miles' drumming

either. And it's pretty obvious that the freer style of Mitchell was

much better suited to Hendrix that the straightahead pounding of Miles.

But there was no doubt more to it than that. Douglas again: "The problem

with me and Jeffrey is that like everybody used to come to me and ask

me to do things which I didn't really have any official capacity to do.

And then Jimi wanted to do it and Mike would get in the middle and it

would get very confused and Jimi would run away from it all."

And Douglas suggests not only musical differences but sheer

mismanagement. "Jimi had a lot of respect for Chas and he loved him and

he would probably have been very happy for Chas to come back into the

scene at any time. 'Cause I think Chas really knew his music and

understood where Jimi was at and probably would have evolved with him,

if he'd stayed. But Mike, not knowing any of these things, only knew the

success formula and regardless of whatever else Jimi wanted to do, Mike

would keep pulling him back or pushing him back into it...And the way

the gigs were routed! I mean, one nighters - he would do Ontario one

night, Miami the next night, California the next night. He used to waste

him on a tour - and never make too much money because the expenses were

ridiculous."

But to return to the Buddy Miles situation. Nothing in the Hendrix story

is ever that simple or even straightforwardly complicated. It's

suggested that Miles was eased out by Jeffrey to split Band of Gypsys so

that the success formula of the Experience could be brought back. And

the Experience were definitely all together for an interview in New York

in February '70. But was it strictly Jeffrey's doing? Had not the Band

of Gypsys - or Buddy Miles at least - proved to be incompatible at the

abortive Peace Rally gig in January?

***

Perhaps. Perhaps not. Redding appears in Welch's book with another

confusing quote: "I remember going to see him at Madison Square Garden

when he was playing with Buddy Miles and Billy Cox. Somebody gave him a

tab of acid just before the show. He was completely freaked. And he

freaked the audience and made a bad name for himself. That was around

August or September 1970." Which in fact was an impossible date for

Miles, Cox and Hendrix to have been playing together. Was Redding's

memory faulty? And so can we imply was it only the acid that had ruined

that gig?

Whatever, Hendrix says it all in that February '70 Experience interview

with Cuitar Player: "It was just something where the head changes, just

going through the changes. You know sometimes there's a lot of things

that add up in your head about this and that. And they hit you at a very

peculiar time, which happened to be at that peace rally - and here I am

fighting the biggest war I've ever fought in my life - inside, y'know"

(My italics.)

An internal and external war about the way his music was going to go. In

one of his last interviews, published in the Melody Maker the day

before he died, Hendrix talks of having two bands: an Experience /

Gypsys style group and a larger conglomerate: "a big band that I can

conduct and write for. And with the music we will paint pictures of

earth and space, so that the listener can be taken somewhere.'' The Gil

Evans project was presumably a step towards this.

But he definitely knew he had to change: "I've turned full circle. I'm

right back where I started. I've given this era of music everything but I

still sound the same. My music's the same and I can't think of anything

new to add to it in its present state.

When the last American tour finished, I just wanted to go away and

forget everything. I just wanted to record and see if I could write

something. Then I started thinking. Thinking about the future. Thinking

that this era of music sparked off by the Beatles, had to come to an

end. Something new has to come and Jimi Hendrix will be there." Perhaps

the ultimate tragedy is that he isn't.

It's patently obvious that Hendrix did not trust Jeffrey on any aspect -

in spite of Jeffrey's glib statements after his death: ''People outside

the circle mistook this for discontent but it wasn't because Jimi was

intelligent and bright enough. If he wanted to split, he would have

split. As far as being artistically frustrated, Jimi had an incredible

genius about him and the common thing with most artists of that calibre

is that they are constantly artistically frustrated." (Rolling Stone)

And Hendrix had next to no reason to trust Jeffrey. There is, for

example, the fantastic story of the Hendrix "kidnapping" that Curtis

Knight relates.

Hendrix wanted to release a double album (presumably the one that he was

working on with Douglas) but his management said that ''there wasn't

enough public demand" and that they would release a single album. Says

Hendrix: "Before I realised what had happened I found myself forcibly

abducted by four men. I was blindfolded and gagged and shoved rudely

into the back of a car. I couldn't understand what the fuck was going on

as I lay there sweating with some one's knee in my back.

I was taken to some deserted building and made to believe that they

really intended to hurt me. They never did tell me why they abducted me.

The whole thing seemed very mysterious because after a while I realised

that if they really had intended to hurt me they would have already

done it by this time.

"And the whole thing seemed even more mysterious when I was rescued by

three men supposedly sent by the management. They really effected a

story book rescue."

So Hendrix knew what he wanted, needed, had to do if he was to stay

himself. But it wasn't as simple as that. Unfortunately for him his

personality was such that he was unsure of himself - he was indecisive

and hated any aggravation.

Alan Douglas: "Jimi was afraid of confrontations with people. He didn't

want arguments. He just used to walk away from it all and almost agree

to everything. He really was a nice person, and he was very shy."

And: "One of the reasons why he never left Jeffrey is because he felt

the need for somebody, regardless of who it was, just the fact that

there was somebody there."

He needed someone to look after the hassles but it also needed to be

someone he knew. He had a need for familiar faces, thus his repeated

attempts to get Chandler back and the resilience of the Mitchell /

Redding / Cox axis. PR man Robin Turner is again quoted in the Welch

biography: "He didn't trust Jeffrey but better the devil you know..."

Enter Alan Douglas, musically in sympathy with Hendrix, a friend and

familiar face and someone he could trust, not apparently a devil. So on

the Wednesday night, says Douglas, Hendrix asked him to be his manager

again. Douglas had always refused before not being into management, but

Hendrix "wasn't concerned about managers. He was concerned about

somebody coming in to say, yes I'll handle it. So I said yes." And he

left the next day to meet Hendrix' attorney in New York.

On the question of asking Chas the same thing on the same night: "He

always loved Chas, you gotta remember that. He signed with Chas

Chandler; he inherited Mike Jeffrey. He always had a really good warm

feeling for Chas. Chas really helped on that first album and he really

felt alone after Chas left so I don't doubt very much at all that he

talked to Chas about those things. Chas probably said no; that's why he

asked me that night, or something."

So things finally seemed to be coming together.

Douglas: ''I mean, he wasn't fucked up or depressed or anything like

that. I had some of the best times of my life with him in the last

couple of months when he was alive 'cause he knew it was evolving. He

knew that it was going to be over soon. And he could have done it a lot

easier but he was avoiding the confrontations with everybody and all

that mess that he knew he was going to get into. But it got so bad that

he finally left completely - he stopped recording at his own studio, he

wouldn't talk to Jeffrey anymore. Jeffrey didn't see him for the last

month before he died.

And it was straightened out. See, he had asked me a few times to go and

straighten the business out. And every time I did it he didn't make his

own presence available and left. And I got messed up with it and I told

him, hey, don't put me in this position anymore. So the last time that

happened, I said, hey, you take care of your business then I can go on

and do it.

"Because it was really a very simple situation: like, everybody put the

contracts on the table and have a good attorney sit down and straighten

everybody out. It could have taken three hours at one meeting.

"I always told him to leave the management thing alone, to let them have

their twenty per cent; it didn't matter. He was making so much money.

It was tax money anyway so let them have their percentage and when their

contracts were all over he was free of it. All we wanted to be able to

do was to work without involvement with those people. So it was all

working out - and maybe it was supposed to go down this way, I don't

know."

And Monika Danneman agreed that he was happy: "Business problems were

not worrying him because he knew what he wanted to do.'' (Rolling Stone

October 29 1970).

But Eric Burdon added a less optimistic note, speaking about the night

of the War jam: "We knew things weren't all that good with him but we

did our best to let him know that we were there to help him."

***

And Chas Chandler, quoted in Chris Welch's book, adds another less

sanguine statement: "somehow I wasn't surprised. I don't believe for one

minute that he killed himself. That was out of the question. But

something had to happen and there was no way of stopping it. You just

get a feeling sometimes. It was as if the last couple of years had

prepared us for it. It was like a message I had been waiting for."

And Joe Boyd, who made the 'Hendrix' film, also had reservations about

Hendrix' move to Douglas from Jeffrey: "From what I know of Jimi's

pattern throughout the rest of his life I don't think he was capable of

doing this - he hated confrontations so much. Then again, I think he'd

gone too far with Alan Douglas."

And there are others who have little sympathy for Douglas. Nevertheless,

Jeffrey stands out as being the easiest to typecast as the villain of

the piece. But again, it's never that simple.

Take this statement for example: "He was an up, one of the highest

people I've ever known and he was getting more and more spiritual. To my

mind, his music was the music of the new religion.

His stage image halted him though, and that was frustrating for him.

That old ghost from the past - the humping the guitar, the 'Foxy Lady'

stuff. Because that wasn't the true Jimi Hendrix, that ballsy, raunchy

image. And as he was becoming more spiritual, he wanted more to fling

that image off and just play his music." (Taken from the Rolling Stone

report on the funeral)

Who said that? Alan Douglas? Chas Chandler? Monika Danneman? In fact, Mike Jeffrey.

Or was that rationalisation after the event, mealy-mouthed bullshit?

Certainly, the unsympathetic - and downright shoddy - programming of the

postumous albums that Jeffrey compiled ('Cry of Love', 'Rainbow

Bridge', 'Hendrix In The West' and 'War Heroes') amply demonstrates

Jeffrey's lack of awareness of where Hendrix was at.

But even Alan Douglas, who should have little enough sympathy with

Jeffrey, had this to say about him: "Let me tell you something that's

very strange. Despite it all I liked what Jeffrey could have been if

he'd let himself be. That's a strange way to say it...I did not like

what he was but what he could have been...I mean, Jeffrey tried to be a

spiritual man. But he didn't know what it was, he couldn't understand."

There are still even darker theories that Jeffrey was merely a tool, a

mouthpiece for the real villains behind. But that is total conjecture.

Despite it all, Jeffrey seems to have been a rather weak-willed person,

dishonest perhaps, unscrupulous even, but not a truly evil man.

John Swenson in his Crawdaddy article spoke to Mike Goldstein, Hendrix'

PR, a man admittedly much more sympathetic to Jeffrey than Douglas. He

says: "Michael liked to think of himself as a villain but he was too

kind to ever be a villain - that was only an image. Jimi's

disenchantment with Jeffrey, if there ever was any, and I don't believe

there was, was his disenchantment with himself. Jeffrey's only problem

with Jimi was his inability to tell him what to do next."

Whoever you want to believe, Jeffrey will remain a mystery. On 5 March

1973, he was killed - in an aeroplane crash over France. The fact that

he was returning from Spain to Britain to finalise details of the estate

might lead one into paranoid theorising about whether the crash was in

fact an accident. But as far as anyone can be sure about any accident,

this one almost certainly was.

At the time Jeffrey was flying back from Palma to London aboard a

scheduled Iberia DC-9, there was a civil air traffic control strike in

France. The military ATC, working from different control centres, was

called in as a contingency replacement. Because of the different nature

of military aviation control however, this necessitated rigorous

planning limited traffic on each sector and strict compliance with

regulations.

The DC-9 however was assigned to the same flight over Nantes as a

Spantax Coronado, which "created a source of conflict "...

And because of imprecise navigation, lack of complete radar coverage and

imperfect radio communications, the two planes collided.

The Coronado was damaged but remained airworthy; no one was injured. The

DC-9 crashed, killing all 61 passengers and seven crew.

After Jeffrey's death, the estate in total reverted to Hendrix' family.

***

ALAN DOUGLAS reappears in the Hendrix story last year with the release

of the 'Crash Landing' album. Douglas had been called in by Warner Bros.

executive Don Schmitzerle to assess and catalogue the 900 hours of

Hendrix tapes placed in a warehouse by the Hendrix estate. Warners had

rejected the final compilation, done after Jeffrey's death, "Loose Ends"

(which Polydor issued here) and Schmitzerle felt there must be

something better in those tapes.

As it happens, there was. Douglas came up with "Crash Landing"; a second

album 'Midnight Lightning' is due out this month; and there is still

one (or two) albums of (roughly speaking) 'jazzrock' of Hendrix playing

with Larry Young and McLaughlin.

Douglas has also persuaded Warners to withdraw the posthumous albums in

the states (with the possible exception of 'Cry Of Love' which was more

or less complete) so that the dross can be taken out and the remaining

tracks remixed properly. They will be reissued as a single album, "Smash

Hits Volume Two".

This album, along with 'Cry Of Love', 'Crash Landing' and 'Midnight

Lightning' will make up the best of the material that Hendrix was

working on at the Record Plant with Douglas. The double album plus.

Among the tracks were 'Room Full Of Mirrors' (which appeared on 'Rainbow

Bridge' with an 'upsidedown' mix), 'Izabella' ('War Heroes), 'Stepping

Stone' ('War Heroes'), 'Dolly Dagger' ('Rainbow Bridge'), 'Belly Button

Window' (Cry Of Love') and 'Look Over Yonder' ('Rainbow Bridge').

Douglas scrubbed Cox and Miles (and occasionally Mitchell - from later

Electric Lady sessions) on some (most) tracks on 'Crash Landing' and

'Midnight Lightning' and dubbed on studio musicians when the Hendrix

rhythm track, lead line and vocal were there with the band perhaps not

gelling perfectly. Perhaps a dubious practice, depending on your ethics.

But it works. Crash Landing' is commercial / Band of Gypsys-style;

'Midnight Lightning' is looser and bluesier and the Young / McLaughlin

tapes are an indication of the direction in which Hendrix was heading.

As was the projected album with Gil Evans, 'Voodoo Child Plays The

Blues',and the fairly definite talk of his playing with Roland Kirk.

Douglas: "At least what we've got is something suggesting where he would

have gone; if not the extent of what would have happened but at least a

feeling of what he was into at the time."

After all the Douglas albums are released, that will be the end of Jimi Hendrix music of any value at all.

There is at least one piece of music which still exists, but it will

probably never appear. Called 'Black Gold', it was an autobiographical

fantasy suite. It will never reappear because it was stolen along with

everything else from Hendrix' New York apartment when he died.

Douglas: "There was so much bullshit going on in that office with

Jeffrey. Jeffrey had contacts with all the people that worked around

him. He wasn't honouring the contracts so when Jimi died, everyone who

could have from that scene burst into his apartment and stole

everything.

"I mean, there was a stack of yellow pads of paper - about 25 of them -

with tunes, things that he used to write every day. Those are gone.

"And the whole 'Black Gold' suite of ten tunes was incredible. Black Gold was himself, about a musician on the road and so on.

"It was such an incredible piece I insisted that he stay home and finish

it and clean it up before we went into the studio with it. I worked on

it with him in his bedroom. We had a beautiful little cassette machine.

And I remember the last time we did it - he put all the tunes down, put a

rhythm track down, overdubbed a little lead line and vocal.

"It was perfect. Like, forty minutes of incredible music - and his best.

Definitely the best thing he'd ever written and played. And it was very

clean - we had an engineer up there who gave us a beautiful clean

cassette sound.

"So I was desperately looking for that 'cause I knew I could have taken

that one but it got ripped off. I don't know where it is. What they were

gonna do was rip off all the stuff and then blackmail Jeffrey to get

the money out of him. So there's a couple of kids in New Jersey that got

some stuff and the two people that worked in the office they got a

bunch of stuff and then Jeffrey brought a lot of stuff up to his house

in Woodstock. It got ripped off out of there.

"But 'Black Gold' was the last thing he did. I heard it one time and it

was finished. We actually edited it there and everything, so we had

every tune down and the transitions between each tune and everything.

It's gone with him some where He's singing 'Black Gold' up there

somewhere. And strangely enough it had an ending just like that.

"Black Gold melts at the end, he melts...he disappears on stage..."

JIMI HENDRIX LIVE AT BERKLEY

5/30/1970

Wednesday, May 14, 2025

mailto:radioman2029

yahoo.com

This is a nonprofit web site it is just a tribute to Jimi Hendrix

yahoo.com

This is a nonprofit web site it is just a tribute to Jimi Hendrix

This site is © Copyright Brian Harper 2004-2016, All Rights Reserved.

myspace web counter

Free web templates

|

|

|

JIMI MOTHER

MITCH MITCHELL

AL HENDRIX JIMI'S DAD

|

|