We Begin

It took seven years to take Rent from its idea to its

previews, and the thing to know about Jonathan Larson is that the week

before the first preview at New York Theatre Workshop, when Jon felt

the first thump of the aortic aneurysm that would carry him away, he

was laughing. Silently. He was laughing on the inside. Director

Michael Greif and the cast were rehearsing the song "What You Own" (the

lyrics are about dying at the end of the millennium) when Jon collapsed

at the back of the theatre and asked for an ambulance. Fearfully, he

told his friends later that he couldn't believe that the last song he

would hear was his own song about dying. The ambulance took him to the

nearest hospital. He had eaten a turkey burger for lunch, and the

doctors diagnosed food poisoning and pumped his stomach. Then he went

home. A few days later, after another incident, doctors at a second

hospital said Jon had the flu.

The night before Rent's first preview, January 25, 1996, Jon

went to a dress rehearsal at New York Theater Workshop, where a crowd

of friends and supporters was whooping and stamping their feet. He was

interviewed by a reporter from The New York Times, who told him

off the record that he thought the play a marvelous achievement. Then

he went home, put on some water for tea, and died. His roommate found

him on the floor of the kitchen, beside his coat. Jon was 35 years

old.

Jon told an interviewer once that, "in the theater, the old thing

about how you can make a killing but you can't make a living is

absolutely true. I'm living proof of that."

You know what happened to the play next - you're part of it. The

show has become one of the biggest things ever on Broadway. It's become

the sort of thing a playwright dreams about in the middle of the night,

and in the morning is embarrassed at how wild his fantasies have run.

Rent - Jon's first produced show - is like an athlete that has

won the Rookie of the year award, a gold medal, the World Series, and

the Most Valuable Player, all in the same season. It collected the New

York Drama Critics Circle Award, the Drama Desk Award, The Obie Award,

the Tony Award, and the Pulitzer Prize. Rent was on the cover of

Newsweek. Time called it a "breakthrough," The New

York Times, "an exhilarating landmark." At the 1996 Democratic

National Convention, the cast of Rent sang "Seasons of Love."

Movie and television stars have sat in the seats you've been sitting

in, and afterwards, at the Nederlander Theater, they've gone backstage

to sign a long brick wall, a kind of Broadway Wailing Wall - Spike Lee,

and Billy Joel and Jodie Foster - forwarding their best wishes and

congratulations to Jonathan and the cast. People in the cast like

Daphne Rubin-Vega - she plays Mimi - say they recognize the same

audience members coming back to the Nederlander ten, fifteen times. If

a young playwright told you this was a fantasy of theirs, you'd smile

at their ambitions, and they'd walk away embarrassed. But here it is

true.

Rent is where Jonathan's friends feel closest to him. They

say it's like getting to spend three more hours with the playwright.

When the actors sing, they are somehow reassembling the personality of

Jonathan. And then there's the play's message about living each day as

if it is your last. Everyone wonders how a man who didn't know he was

about to die could write a play that seemed to take full account of his

own early death. There's so much of Jonathan there, but the fact

remains that it isn't only Jonathan. There are other voices here too,

other personalities that shaped Rent, who took an idea that had

been batting around at Jonathan for seven years, and gave it sets and

costumes and flesh and bones and lights and actors and life. It took

many other people to allow Jon's voice the clearest opportunity to sing

its own song. Here is how it happened:

Jon's early life isn't exactly what you expect. Nor is it what you

might have read about. Journalism has made his posthumous success seem

like a wild, out-of-nowhere surprise, but Jon was trained for it,

prepared for it. The surprise in Jon's life was the 14 years of rough-

going, not the success.

Jon was born on February 7, 1960, in White Plans, which is about

half an hour outside of New York City. His parents loved the theater,

and took Jon and his sister into town for shows a couple of times a

year. (They took him to see a puppet show of La Boheme when he

was about five years old, which probably helped him see that there was

a lot of flexibility in the old story.) By the time he was in

kindergarten, he was doing things like organizing friends into

productions of "Gilligan's Island" in their suburban backyards; by

third grade, he had written, directed and starred in a play of his own,

and been photographed for the White Plains newspaper. By high school,

he was so famous as an actor that the school, which had no musical

theater program, developed one to accommodate his talents. He won a

four-year, full-tuition acting scholarship to Adelphi University.

Adelphi's theater program was modeled on the prestigious Yale School of

Drama and Jon basically ran the place. For the first time he wrote

musicals of his own, and discovered he was quite good at it. His

professors there remembered him as the best songwriter they'd ever

seen. Senior year, he wrote a letter to Stephen Sondheim, his idol -

the kind of letter a young man writes when he is on the look-out for a

mentor. A few months before graduation, Sondheim invited Jon to his

house for some advice. Jon told the composer he had trained as an

actor but loved writing music. Sondheim advised him to dump

performing: "There are a lot more starving actors than there are

starving composers." So, college degree in hand, Jon came to New York -

the city where he'd always wanted to live - in the spring of 1982,

ready to succeed in real life as he had succeeded in academic life.

Jon was born on February 7, 1960, in White Plans, which is about

half an hour outside of New York City. His parents loved the theater,

and took Jon and his sister into town for shows a couple of times a

year. (They took him to see a puppet show of La Boheme when he

was about five years old, which probably helped him see that there was

a lot of flexibility in the old story.) By the time he was in

kindergarten, he was doing things like organizing friends into

productions of "Gilligan's Island" in their suburban backyards; by

third grade, he had written, directed and starred in a play of his own,

and been photographed for the White Plains newspaper. By high school,

he was so famous as an actor that the school, which had no musical

theater program, developed one to accommodate his talents. He won a

four-year, full-tuition acting scholarship to Adelphi University.

Adelphi's theater program was modeled on the prestigious Yale School of

Drama and Jon basically ran the place. For the first time he wrote

musicals of his own, and discovered he was quite good at it. His

professors there remembered him as the best songwriter they'd ever

seen. Senior year, he wrote a letter to Stephen Sondheim, his idol -

the kind of letter a young man writes when he is on the look-out for a

mentor. A few months before graduation, Sondheim invited Jon to his

house for some advice. Jon told the composer he had trained as an

actor but loved writing music. Sondheim advised him to dump

performing: "There are a lot more starving actors than there are

starving composers." So, college degree in hand, Jon came to New York -

the city where he'd always wanted to live - in the spring of 1982,

ready to succeed in real life as he had succeeded in academic life.

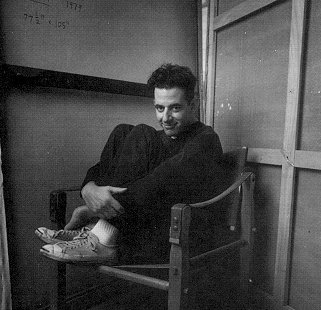

There are some things to know about Jonathan. He had a heightened

appreciation for the incidental pleasures of life. At Adelphi, theater

chairman Jaques Burdick drilled students in a Greek notion called

kefi (the word is pronounced keh-fee) and Jon treasured the

concept. If you had kefi, wherever you lived, whatever was

going on in your life, it would feel wonderful. It was an idea Jon was

going to find useful.

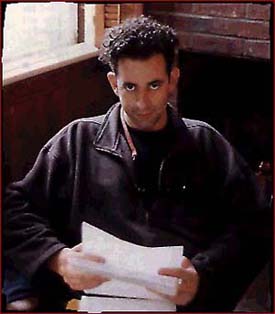

Jon lived a bohemian life in downtown New York. He rented a

scruffy loft that had a bathtub in the kitchen and a crumbling water

closet with a skylight above the toilet, and thick extension cords

running all along the baseboards to feed his computer, his synthesizer,

and his tape decks. For a while, he and his roommates kept an

illegal, wood-burning stove. He got a waiter's job at a SoHo

restaurant called the Moondance Diner. He dated a dancer for four

years who sometimes left him for other men and finally left him for

another woman.

He wrote lots of music in the years between leaving college and

mounting Rent, including two shows that didn't get produced.

And here's another thing to know about Jonathan: He wanted to

transform the musical theater, to make it more modern. He didn't like

that show music hadn't changed since the late 1940s. That

Oklahoma sounded like Oklahoma in 1943 was fine; that a

lot of musicals still sounded like Oklahoma in 1996 was

depressing. All of his downtown friends liked music but none of them

liked musicals; he would explain to them, "That isn't our music uptown

on Broadway; those aren't our characters, these aren't our stories."

Jon had grown up listening to the Who and Billy Joel and Elton John,

along with Sondheim. He wanted to make them one and the same thing.

But after seven years of writing musicals in the city, he hadn't been

able to convince anyone lese that this was the right way to go. That

was when he hit on Rent.

So now here's Billy Aronson, who was a Yale trained playwright, who

loved opera, and who had this idea. Billy wanted to write a musical

updating La Boheme. He wanted it to be about people like himself

- struggling to make art under lousy conditions. Some theatrical

acquaintances suggested Jonathan. They met a few times in 1989, sitting

on Jonathan's roof and absorbing a little kefi. Jon came up with

the title. He didn't like Billy's proposed Upper West Side setting.

Billy wanted to make the show about his friends, and Jon wanted to make

it about his. Jon won. In 1991, he called Billy up and asked if he

could take Rent for his own. Billy said sure. Jon also liked one

more thing about Rent. In La Boheme, the Parisian

bohemians are afflicted with tuberculosis; the whole opera occurs under

its specter. The modern equivalent was AIDS. Jon knew all about AIDS.

He was healthy, but a lot of good friends had HIV, like Matt O'Grady,

his pal from back home. Writing Rent provided one way to make

sense of the experience.

Jon spent a year working on the themes in Rent. Though he

set the show in the East Village, he didn't really live there. Jon

felt out of place in the punky East Village; he was West Village

through and through. Jon didn't want to go alone on tours of the East

Village so he took along Eddie Rosenstein, a filmmaker and friend, who

scouted locations with him.

Back home, he wrote his musical. He whittled his Moondance job

down to three days a week, which left four days for writing. Sunday

nights, Jon would boil a big tub of pasta and a big pot of sauce and

mix them together; he'd eat that for dinner all week. He'd buy boxes

of Shredded Wheat, and break off exactly one and a half scrubby bricks

each morning. He wanted to fuel himself like a machine - without

having to think - so all his thoughts would be reserved for writing.

One day in the summer of 1992, after he'd finished the first draft

of Rent and recorded some of the songs, he hopped onto his bike.

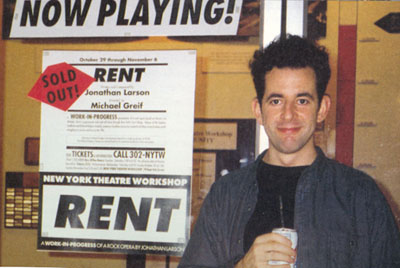

"That now legendary bike ride," remembers Jim Nicola, artistic director

of New York Theater Workshop. The Workshop has just purchased a new

theater on East Fourth Street, "and that summer we were tearing it up

to try and make it more hospitable to the kind of work we wanted to do.

Jon took a ride through the East Village, sort of scouting out

theaters. The doors were open, he heard the construction, and he

wandered in. And he immediately fell in love with the space and

thought it would be perfect for Rent."

It was the right moment for Jon to bring a musical to New York

Theatre Workshop, which had been doing mostly new plays for nine years.

Nicola thought in was high time NYTW mounted a musical. He wanted a

show reflecting the world beyond Broadway, with music that sounded the

way music does today. Jim listened to Jon's tape the night he got it.

"'Light My Candle' was there, and the title song, and 'I Should Tell

You.' The story wasn't quite there yet - there didn't seem to

be a clear story - but the music was thrilling."

It was the right moment for Jon to bring a musical to New York

Theatre Workshop, which had been doing mostly new plays for nine years.

Nicola thought in was high time NYTW mounted a musical. He wanted a

show reflecting the world beyond Broadway, with music that sounded the

way music does today. Jim listened to Jon's tape the night he got it.

"'Light My Candle' was there, and the title song, and 'I Should Tell

You.' The story wasn't quite there yet - there didn't seem to

be a clear story - but the music was thrilling."

New York Theatre Workshop put on a reading of the musical in the

spring of 1993. Nicola was struck by the intensity of responses. Some

friends though it was simply ragged, but others were in love with the

material from the first, no matter its flaws. A young producer named

Jeffrey Seller, who had met Jonathan several years earlier, also felt

the time was right to produce a musical. He had stayed in touch with

Jon, because he, too, wanted to bring rock music to Broadway, and was

convinced that one day, "Jon was going to write a brilliant musical."

He came down to Fourth Street. Jeffrey felt the play was baggy, a

collage with no narrative shape. "There were great songs," Jeffery

remembers, "but there were endless songs." Some producer friends he had

brought with him left at intermission, assuring Jeffrey the work was

unsalvageable. Jeffrey was still interested, though - as long as Jon

found a story as good as the music.

Jon sent a letter to Stephen Sondheim, asking for advice and

assistance. The older composer responded by encouraging Jonathan to

apply for a Richard Rogers Foundation grant. Jonathan eventually won

$45,000 to support of workshop production of RENT.

What they needed now was a director. Jim immediately suggested

Michael Greif, a young New York director who had recently become

artistic director of the La Jolla Playhouse in San Diego. He sent Greif

Jon's tape and script. Greif listened to the tape on a Walkman flying

from California to New York. The script seemed shaggy - "What impressed

me," he remembers, "was its youth and enthusiasm, and that it was a

musical about contemporary life. Jon was writing about some people I

felt I knew, that I sort of loved, or had loved in my life." What Jim

wanted in a director was a counterweight to Jon's kefi

philosophy, which had allowed him to treat dark subjects like AIDS,

homelessness, and drug addiction with optimism. Michael was hard-nosed

and cool-headed. He met with Jim and Jonathan in January of 1994, and

the three set to work on bringing the script to the level of the music.

"It was a very fragile material at the time," Jim recalls." And it was

so easy for it to become sentimental or hokey, or any number of things.

I felt Michael had the right sort of dryness and sharpness to balance

Jonathan's writing.

Jim saw his instincts had been right as soon as the three got down

to shaping the script in Jon's loft. They met for a week in the middle

of the spring, preparing for the workshop scheduled for November. They

went over the script scene by scene, moment by moment. Immediately, the

dynamic between Jonathan and Michael slipped into a productive yin and

yang. Michael was afraid there was something self-congratulatory about

the young bohemian heroes of the show; so Jon toned down the lyrics of

"La Vie Boheme." Michael fretted about the homeless characters - that

they not simply serve as East Village window dressing, as moral

scarecrows where Mark and Roger could drape their good social

conscience; so Jonathan wrote the new song, "On the Street," where a

homeless woman gives Mark a stern telling off. Most importantly,

Michael had reservations about the message of the show, the "No Day But

Today" cheerfulness of the Life Support meetings. Michael had friends

with HIV, just as Jon did, and they were not cheerful about it. Jon

added the new scene of Gordon questioning the Life Support credo. And

Jon himself kept Michael from becoming too hard-nosed and cool-headed.

"What Jon gave Michael was some of his hope and heart and generosity of

spirit. And what I think Michael gave Jon was some edge and realism and

complexity. It was a good marriage," remembers Anthony Rapp, who plays

Mark.

The three met again that summer at Dartmouth College, where NYTW

ran a kind of working camp for its affiliated artists. Michael and Jon

talked plot. One large problem, they agreed, was the relationship

between Maureen and Mark; in these drafts, a major plot point was Mark

winning Maureen back. Michael didn't like it. "My position was, if

they're gonna be lesbians, let them be lesbians. Don't make them about

going-back-to-their-man."

In October, back in the city, Michael worked out the "performance

vocabulary" of Rent. For budgetary reasons - and also because it

suited the nature of the characters - it was decided to have minimal

props. Michael suggested the three "Frankenstein" tables, which could

be made to serve so many functions in the show. Because it was rock,

Michael played around with microphones, with actors singing directly to

the seats: "We were very anxious to take advantage of the fact that it

would be as much a concert as it was a play."

For all its flaws, the November workshop was a tremendous success.

It ran two weeks with the audience growing larger and more enthusiastic

each night; by the last week it was sold out.

Anthony Rapp, a cast

member of the November workshop, remembers the excitement: "I kept

telling people it was going to be an event. We knew it needed work. But

people I trust and respect - friends and collaborators - would come

down and be knocked out by it."

Anthony Rapp, a cast

member of the November workshop, remembers the excitement: "I kept

telling people it was going to be an event. We knew it needed work. But

people I trust and respect - friends and collaborators - would come

down and be knocked out by it."

Jim Nicola thought it needed work, too. But the responses he was

getting from his friends were just what Anthony was hearing. "There was

a lot of passion - again, the most striking thing was the intensity of

opinion about it. There was a large segment of people whose tastes I

trusted who just loved it, and didn't care what the problems were. I

felt even more convinced that there was really something strong here."

Jim found himself moving towards an exciting, scary, stirring decision.

"Rent was the kind of show to bet the company on."

A Year in the Life

The second week, Jeffrey Seller returned to East Fourth Street. He

brought his business partner, Kevin McCollum. Sitting down in the front

row, seeing the three tables, remembering the plotless show he'd seen a

year earlier, Jeffrey had time for a crisis of confidence. He turned to

Kevin before the show and warned him, "This is either gonna be

absolutely brilliant or it's going to be a piece of crap." At

intermission Kevin nudged Jeffrey and said, "I'm loving this. Get out

the checkbook."

A couple of nights later, the two brought a business associate

named Allan Gordon to NYTW. The three had worked together previously

on the national tour of "The Real Live Brady Bunch." Allan was equally

enthusiastic - like Jeffrey and Kevin, he was overpowered by the music.

That night the three decided to work on the project together.

After the holidays, Jim, Michael and Jonathan sat down again in

Jim's office. Jim had thought it over, and talked to NYTW's board

members. The Workshop decide to stage a full production of Rent

the following year with the help of Seller, McCollum and Gordon, who

would get the commercial rights in return. The budget would be

$250,000 - twice the cost of anything NYTW had ever mounted.

After the holidays, Jim, Michael and Jonathan sat down again in

Jim's office. They spoke about what need fixing. The show had no single

story, no primary narrator - in the November workshop, all the

characters told the story; when they had something to say, they turned

around and said it right to the audience. And the characters

themselves, especially Maureen and Joanne, needed refinement. Jim gave

Jon a task: Could he boil the plot down to a single sentence? The

sentences Jon first turned in were impossibly long, crammed full of

clauses and parentheses and second thoughts. But as Jim anticipated, as

the sentence came into focus, so did the play.

Jim decided to hire a dramaturg to work with Jonathan. Dramaturgs

work with playwrights as shapers, advisers and editors. Jon did a lot

of interviews before meeting Lynn Thompson. They hit it off right away.

From the first, Lynn seemed to be on Jon's wave length. She was able to

speak in a voice that sparked Jon's enthusiasm. Jim put the two on a

schedule; Jon would deliver a revised draft by the summer's end.

Rent was to begin rehearsals in the fall.

Jon had found another strong collaborator. Lynn suggested he work

up biographies of the characters, that he write a version of

Rent told through each person's eyes. Her belief was that once

Jon understood the story completely, once he really had the characters

under his belt, the rewriting of the play would come in a simple burst.

They worked through the summer, discovering a structure for

Rent.

By October they had a new draft. Jon was confident his six years of

work were over. Actors read the script aloud to everyone. Jim and

Michael were both struck by the changes, but they knew they weren't out

of the woods. The characters were sharper, but Jon had done some

structural fiddling, turning much of the show into flashback. The first

act began with Angel's funeral and Mark wondering, "How did we get

here?", with the rest of the story catching up from there. No one was

comfortable with this except the playwright. The Maureen-Joanne

relationship was finally working, but their second act duet was by all

accounts miserable. "One of the worst songs ever written," Michael

remembers with a laugh. "The songs was a straight out cat fight, the

lovers sniping at each other, Maureen telling Joanne, 'You're the

hepatitis in my clam.'"

Jeffrey was also concerned. The show was supposed to go into

rehearsals in six weeks and Rent didn't feel ready to him. "On

the one hand, the new script made a huge, wonderful leap from the

workshop - a gigantic creative stride - but it wasn't there yet. Now

it's late October and we're in casting. And the show starts rehearsing

in December." Jeffrey dashed off some quick, blunt notes on what he

felt need to be changed in Rent before the production could move

ahead.

Jeffrey's notes were intended for Jim and Michael, but Jon got a

hold of them. What the notes called for was another rewrite. Jon didn't

want to do any more writing. "There was real terror the production

wouldn't happen," Michael remembers. "It was a tense few days. Jon was

very upset and very frustrated. But what it came down to was, we all

want this to be as strong as it can be. No one thinks this is finished,

so we should have another go at it." Jon turned to Sondheim one last

time, and Sondheim reminded him of a key proposition: theater was

collaborative. Part of Jon's job was to take into account what his

collaborators felt. So Jon signed on.

Michael wanted a simplified structure, with a clearer emotional

division between the two acts: "The first act should be much more the

celebration, and the second act should be a lot of the ramifications

and sorrows surrounding these lives." Jon finally quit his job at the

Moondance Diner. His friend Eddie Rosenstein remembers, "After he left

the diner, and he announced that he was a full-time professional

musical playwright, his spirits soared. That's all anybody wants to do

in life, isn't it? A chance to do what they do."

During Jon's rewrites the show moved in casting. Michael wanted a

youthful, sexy cast, and he and Jon leaned toward young performers who

seemed to have some connection with their characters, whose spirit

could add dimensions to the work. The cast seemed to invigorate Jon.

"He was really inspired by this company," Michael says. "We still

needed the Joanne-Maureen song. And Jon really wisely said, 'let me

just sit with these actors, and let me bring you something.' And then

what he brings me is 'Take Me Or Leave Me,' and I'm totally thrilled

out of my mind."

In December, with casting done and rehearsals about to begin, Jon

handed in the final version of Rent. Jon had worked a

succession of 20 hour days. "He had completely cleaned up the

narrative," Jeffrey says, remembering everyone's excitement with this

last creative step. "In December, when I saw the first sing-through

with the full cast, I knew we were in great shape. I gave Jon a hug

and told him, 'you done good.'"

One thing that struck Jim was how tired - even in his excitement -

Jon seemed after pulling off this final rewrite. "But I do think of

theatre as sort of an Olympic event. It's a rare moment in one's life

when you really push way beyond what you think your endurance is.

That's what Jon did." They had the draft of the show everyone had

wanted for three years. And Jon finally delivered to Jim his one

sentence summary of what story Rent told: "Rent is about

a community celebrating life, in the face of death and AIDS, at the

turn of the century."

From December on, it was a quick sprint to the show you've seen [or

at least know and love]. There were a lot of what Jon called

"programming changes": shifting songs from one position to another,

seeing where they fit best. In January, Jim watched a rehearsal with a

group of NYTW board members, and the emotional response to RENT

was extraordinary. "It continued to get even tighter and better through

rehearsals," Daphne Rubin-Vega remembers. Then The New York

Times got wind that a rock musical based on La Boheme was

going to premiere on the 100th anniversary of the original La

Boheme. No one had know this; it was a simple fluke. The night of

the final dress rehearsal, Jon was sick with a sore chest and a fever.

But he took a taxi to Fourth Street, watched the show, and sat for his

interview with the Times. The last thing Michael and Jim

remember saying to him was to take it easy and sleep well; they'd see

him and Lynn in the morning. Jon died an hour later.

After Jon's death, there were few revisions. Lynn, Jim, Michael and

music director/arranger Tim Weil (who would take charge of the show's

musical elements after Jonathan died) would meet and attempt, by

looking over the many drafts of Rent, to decide what changes

Jonathan would have approved. They would put their heads together and

out of their three component visions try to come up with a close

duplication of Jonathan's. When the show premiered, they knew they had

something special on their hands. Jon's death added an explosive,

powerful element to the cast's understanding of the play. "The company

had already come together so well, but that event of Jon dying just

brought us together that much more strongly," Daphne remembers. "It let

us remember that the bottom line is really about what you do with this

experience, because tomorrow isn't promised you. There was no more

powerful way of receiving that message than from someone who was

completely healthy and died. Someone whose life was just beginning."

Jon's friends had to go to his old loft to clean the place out.

His oldest, best loved girlfriend found a diary Jon had kept during his

last years of college. "When I die," he had written, "whenever and

wherever that may be, I wish to be cremated, and I want my ashes to be

thrown to the sunset with music and dancing and crying."

The day of Jon's death, no one at the Workshop was quite sure what

to do. The first performance was scheduled for that evening. Jim

Nicola's first inclination was to cancel, but he knew they needed to do

something for Jonathan's memory. Jim was uneasy. The first act, in

particular, involved a lot of tricky dancing and jumping on tables. It

hadn't been completely rehearsed, and he was afraid there would be

injuries. Eddie Rosenstein urged him to run the whole show full out. By

the evening, Jonathan's friends were streaming into the theatre, his

parents were there, New York Theatre workshop was filled to capacity

with people Jon loved - friends, family and colleagues. Jim decided on

a sing-through - no movement, just songs. Throughout the first act, the

cast was able to hold their seats. But very slowly, they began to rise.

They acted, they danced. "It was incredible and terrible," Anthony

remembers. "It was like we had to do it. We were all sobbing and

crying." The lighting people made their way to the lighting booth; the

sound manager began to pick up his cues. "They couldn't contain

themselves," Eddie remembers. "The audience was reaching out to the

cast. They were crying and cheering. By the second act, it was no

longer contained. It was the full show run full-out, with every line

hit for greater and greater meaning. If emotion could have become a

physical force, the roof would have blown off, the weather would have

changed." The second act ended. There was a huge ovation, the cast

slowly left the stage, and the audience stayed in the theater. No one

was sure what to do. The cast returned and sat down in the front row.

Finally, a single voice called from the audience, "Thank you, Jonathan

Larson," which brought the evening's loudest, final burst of applause.

The day of Jon's death, no one at the Workshop was quite sure what

to do. The first performance was scheduled for that evening. Jim

Nicola's first inclination was to cancel, but he knew they needed to do

something for Jonathan's memory. Jim was uneasy. The first act, in

particular, involved a lot of tricky dancing and jumping on tables. It

hadn't been completely rehearsed, and he was afraid there would be

injuries. Eddie Rosenstein urged him to run the whole show full out. By

the evening, Jonathan's friends were streaming into the theatre, his

parents were there, New York Theatre workshop was filled to capacity

with people Jon loved - friends, family and colleagues. Jim decided on

a sing-through - no movement, just songs. Throughout the first act, the

cast was able to hold their seats. But very slowly, they began to rise.

They acted, they danced. "It was incredible and terrible," Anthony

remembers. "It was like we had to do it. We were all sobbing and

crying." The lighting people made their way to the lighting booth; the

sound manager began to pick up his cues. "They couldn't contain

themselves," Eddie remembers. "The audience was reaching out to the

cast. They were crying and cheering. By the second act, it was no

longer contained. It was the full show run full-out, with every line

hit for greater and greater meaning. If emotion could have become a

physical force, the roof would have blown off, the weather would have

changed." The second act ended. There was a huge ovation, the cast

slowly left the stage, and the audience stayed in the theater. No one

was sure what to do. The cast returned and sat down in the front row.

Finally, a single voice called from the audience, "Thank you, Jonathan

Larson," which brought the evening's loudest, final burst of applause.

By David Lipsky

Thank you.

For more information, we highly recommend that you buy the Rent Book (or, as we prefer to call it, the Rent Bible.) Click here to order to the book from Amazon.com, at a 30% discount off the regular price! (Good deal for a good book!)

|