by Vincent Torley, Ph.D. Who am I?

Over at Why Evolution is True, Professor Jerry Coyne has been busily promoting the writings of a man he describes as "The First New Atheist": the acclaimed writer, H. L. Mencken (1880-1956). Professor Coyne promised his readers one week of daily posts featuring quotes from the great essayist, on the follies of religion, and he's kept his word: he's just completed Day Seven of his postings.

When I first read of Professor Coyne's choice of patron for the New Atheist movement, I quietly marveled. Professor Coyne is a very well-read man, and when he makes a choice, you can be sure that he has given it a lot of thought. It was he who officially declared Aratina Cage's logo of a red A with two horns to be the Gnu Atheist symbol, and his choice has been vindicated by the surge in the logo's popularity. I therefore have to assume that Coyne knew what he was doing when he nominated H. L. Mencken as the patron of the New Atheist movement. So far, visitors to his Web site have strongly supported Coyne's choice. Coyne has been very enthusiastic in his promotion of Mencken, even going so far as to refer to him as "the imperishable Henry". What's next, I wonder? Will we see a readers' contest for the best halo design?

Now, when one nominates a patron for one's movement, one should be careful to nominate an individual whose greatness is readily apparent and whose faults, whatever they may be, are capable of being overlooked. A patron need not be perfect, but he/she should be, at the very least, an admirable person: a pioneer in whose steps others can follow. To his credit, Professor Coyne has acknowledged Mencken's vindictiveness; but this is hardly a fatal flaw.

The reason for my quiet astonishment when I learned of Coyne's choice of a patron for the New Atheist movement was that only two weeks before, I had stumbled upon some very interesting quotes from H. L. Mencken's writings on pages 397-398 of Thomas Sowell's Intellectuals and Society (Basic Books, Revised and expanded edition, 2012). I therefore knew that Professor Coyne's nomination of H. L. Mencken as the First New Atheist was an extremely inopportune one – and that's putting it mildly. For the information I now had about Mencken could fairly be described as political dynamite. Yes, I said "dynamite."

Surely Coyne must know, I said to myself. Surely someone would have tipped him off about Mencken's opinions. And early this week, I found out that he did know. For the last few days, Coyne has been quoting from a little-known book by Mencken, titled Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1956), which was published in the final year of Mencken's life. It's an old book, but Johns Hopkins University Press issued a new edition in 2006. I strongly urge people who like collecting rare books to buy it ASAP, before the 15 remaining new copies get snapped up. Alternatively, viewers can read the book online here,which is where I discovered it. Over at his Web site, to the great delight of his readers, Professor Coyne has been gleefully quoting humorous passages from the book, in which Mencken tears apart what he regards as the patently absurd claim that science and religion are compatible.

Now, I'd be the first to acknowledge that Mencken was an extraordinarily gifted writer, even though I disagree with most of his opinions. But when I actually read Mencken's "Minority Report" for myself, I discovered that Mencken's views were even more awful than the ugly sentiments quoted in Thomas Sowell's book. I don't think Coyne's readers will thank him for nominating Mencken as the first New Atheist after they've read this post. They're more likely to ask him, "What were you thinking?" I'd say Professor Coyne definitely has some explaining to do. I sincerely hope he does so, and I am looking forward to his response.

So, who was H. L. Mencken?

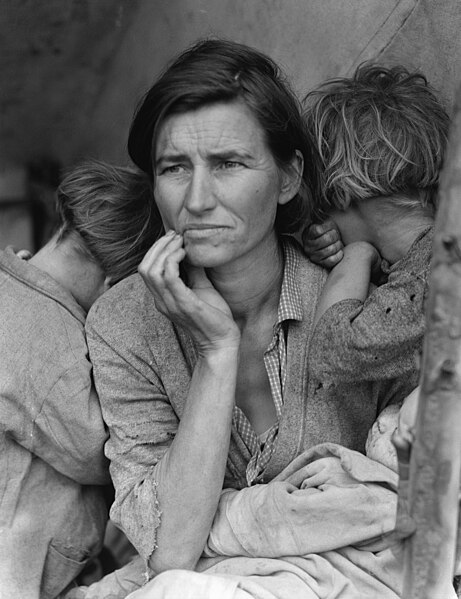

H. L. Mencken in 1932. Images courtesy of Wikipedia.

Readers under the age of 40 might not know H. L. Mencken, so I'd better introduce the man. To most people, Henry Louis Mencken is best-known as the author of The American Language, an acclaimed and highly readable study of how the English language is spoken in the United States, and for his reporting on the 1925 Scopes trial, which he dubbed the "Monkey Trial." (By the way, if you want to know what the movie Inherit the Wind got wrong about the trial, click here. Short answer: practically everything.) Mencken is also widely admired as a peerless satirist, a hard-hitting journalist and an acerbic critic of Christian fundamentalism, organized religion, anti-intellectualism and Prohibition.

But who was the real H. L. Mencken? In this post, I have put together a collection of excerpts from his writings, with the aim of demonstrating that despite his personal warmth, his generosity, his unfailing courtesy to women and his unflagging loyalty to his friends, the man held appalling and callously inhuman views, even for his time, on matters relating to race, eugenics, crime and punishment.

Mencken's good qualities

Before I detail Mencken's hideous faults, however, I think it is only fair to present the man's good side. I’d like to begin by quoting the testimony of a man who knew Mencken for several decades: the Jewish publishing giant Alfred A. Knopf, who praised him as a generous, intelligent friend in a personal tribute entitled, "For Henry With Love" (The Atlantic Monthly, May 1959). In his essay, Knopf revealed a little-known hidden side to Mencken the man:

He [Mencken] had the reputation ... of being a burly, loud, raucous fellow, rough in his speech and lacking refined manners. How mistaken this opinion as I learned a little later, when on a visit to Washington I introduced Blanche [Knopf's wife] to him. He met her with the most charming manners conceivable, manners I was to discover he always displayed in talking with women....I knew Mencken for more than forty years, intimately for well over thirty. Books have been published which describe him as a man I find it difficult to recognize. His public side was visible to everyone: tough, cynical, amusing, and exasperating by turns, but everlastingly consistent. The private man was something else again: sentimental, generous, and unwavering – sometimes almost blind – in his devotion to people he liked.

Mencken was only married for five short years of his life: his wife, Sara Haardt, a Professor of English literature at Goucher College in Baltimore, suffered from tuberculosis, but Mencken supported her writing, and he was grief-stricken when she died in 1935.

Mencken's views on the female sex were fairly "progressive" for a man of his era: he considered women to be more intelligent than men, and he wrote highly of them in his highly acclaimed work, In Defense of Women. He hailed the advance of women’s civil rights, with one notable exception: he loathed the suffragettes.

Mencken was also outspoken in his defense of the oppressed, even at times when nobody else dared to defend them. Writing for The Baltimore Sun in the 1930s, he fearlessly denounced mob lynchings of African Americans, and sharply criticized other newspapers for failing to address the issue. He later urged President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to take in all of the Jewish refugees from Hitler’s persecution who wanted to emigrate to America. Sadly, his plea was ignored, but Mencken did not stand idly by: he personally helped some Jews to flee to America.

Mencken: the bad and the ugly

I've said that Mencken had a bad side. Let me begin with his character.

Everyone has their share of personal faults and failings. One fault of Mencken's was that he was not above engaging in character assassination. This, in a journalist, is an inexcusable flaw. I realize that many readers will want to see proof of my accusation against Mencken, and I shall supply it in my next post.

I'd now like to pass on to the man's views, which were frankly horrid, and at times downright nutty. What follows is merely a short summary; I shall provide detailed documentation for my claims below.

Mencken considered the vast majority of black people to be barely above gorillas, mentally speaking. (He did acknowledge, however, that a tiny minority of blacks were intellectually gifted.) As I'll demonstrate below, Mencken's views on African Americans' mental abilities were unusually racist, even for the time in which he lived. His opinion of Native Americans was even lower than his opinion of black people: not one of them, he said, had accomplished anything of distinction in fields outside the military.

Although Mencken helped Jews who were fleeing Hitler's Germany, he regarded the Jews as second-rate thinkers, and despite his total lack of scientific training, he presumptuously believed he could show that Einstein’s theories about space and time were wrong.

Mencken, who was German-American, greatly admired the Prussians, but he held the English Anglo-Saxon race in contempt as a race of weaklings. He considered the poor Southern whites of Appalachia to be the "purest" Anglo-Saxons in America, racially speaking, because of their geographic isolation, and he loathed these people so intensely that he wrote that the world would be better off without them. Some of them, he declared, were more like apes than humans. He even referred to them as "mountain baboons."

Mencken was also an unabashed elitist, who contended that some individuals are vastly superior to others, not only in their achievements but also in their mental abilities. The capacity to think, he maintained, had appeared only in the last 10,000 years of human evolution; even today, many people were mentally little better than smart dogs. There was very little difference, he wrote, between the smartest dog and the stupidest (normal) human being, and the mental difference between the smartest and the stupidest people was much greater than the difference between men and dogs. Mencken believed that only great individuals really mattered in the scheme of things, and he regarded the great majority of human beings as mere cockroaches, who never even had a single original thought in their lives.

Although he was a fierce defender of free speech and equality before the law, Mencken utterly despised democracy, arguing that voting was a privilege that had to be earned. He maintained that only the best people should govern society, and that they deserved all the privileges they got - including the right to commit adultery with women of the lower classes (an act which, he said, benefited both the upper and lower classes).

Mencken advocated the sterilization of criminals, poor people and the unfit. Opposition to the sterilization of criminals, he said, could be justified only on religious grounds, which he abruptly dismissed. Poor people had no right to bring children into the world unless they could support them; and if anyone had a child they couldn’t support, they should be sterilized immediately. Sterilizing the unfit was simply a matter of genetic common sense: you couldn't possibly hope to improve the quality of the human race by allowing its weakest stock to breed.

Mencken also declared roundly that nine-tenths of the people whose lives were prolonged by physicians were not worth saving. Their death, he said, would be a public benefit. He was all for legalizing suicide, arguing that people who ended their lives usually had a perfectly logical reason for doing so, and that they should not be hindered from ending their lives. Consistently, he maintained that anyone wishing to put their lives at risk by taking lethal drugs should be perfectly free to indulge their habit.

Mencken was very keen on executing large numbers of criminals, too: he thought that America should execute at least 2,000 people every year, instead of the then-current level of 130. He argued that England had gotten rid of its criminals through mass executions in the 18th century, which was why the English today were so law-abiding. America should follow England's example and kill off its hardened criminals too, he said. It was the only way to achieve a well-ordered society.

As I mentioned above, Mencken despaired of democracy, but he opined that a world conqueror with a "really first-rate" mind could work wonders in reforming Europe's system of government. The only real problem, as Mencken saw it, with this plan for a benevolent world dictatorship was that there was no way to ensure that the dictator's successor would be as intelligent as he was.

Christopher Hitchens' verdict on Mencken

I hope by now my readers are convinced that Mencken suffered from an appalling lack of compassion for the great majority of his fellow human beings, whom he regarded as intellectually deficient, and therefore less human than he was. Why, one wonders, did Professor Coyne nominate this flawed individual as the First New Atheist? He might have profited from reading a review (A Smart Set of One, New York Times, November 17, 2002) written by his old friend, the late Christopher Hitchens, who perceived Mencken for what he was: a disciple of Friedrich Nietzsche who eagerly espoused the philosopher’s social Darwinism. To quote Hitchens:

...Mencken was a German nationalist, an insecure small-town petit bourgeois, a childless hypochondriac with what seems on the evidence of these pages to have been a room-temperature libido, an antihumanist as much as an atheist, a man prone to the hyperbole and sensationalism he distrusted in others and not as easy with the modern world and its many temptations and diversions as he liked it to be supposed….Nietzsche despised both Christianity and democracy, as did Mencken.... But for Mencken, the German savant played approximately the same role as does Ayn Rand for some rancorous individualists of our own day. In the celebrated confrontation with William Jennings Bryan, for example, where the superstitious old populist feared that scientific Darwinism would open the door to social Darwinism, Mencken shared the same opinion but with more gusto. He truly believed that it was a waste of time and energy for the fit to succor the unfit. When he had written about Kaiser Wilhelm in 1914 and entitled the essay 'The Mailed Fist and Its Prophet,' he had not attempted to be ironic or critical.

"Social Darwinism" is a pretty strong perjorative term, coming from a man like Hitchens, whose affection for Charles Darwin the man (who would have been appalled by Nietzsche's philosophy) is so well-known. So what did Mencken write about Kaiser Wilhelm, shortly after the beginning of World War I, in 1914? On an impulse, I decided to check out The Mailed Fist and Its Prophet. And this is what I found. The italics are Mencken’s:

I come to the war: the supreme manifestation of the new Germany, at last the great test of the gospel of strength, of great daring, of efficiency. But here, alas, the business of the expositor must suddenly cease. The streams of parallel ideas coalesce. Germany becomes Nietzsche; Nietzsche becomes Germany. Turn away from all the fruitless debates over the responsibility of this man or that, the witless straw-splitting over non-essentials. Go back to Zarathustra: 'I do not advise you to compromise and make peace, but to conquer. Let your labor be fighting, and your peace victory.... What is good? All that increases the feeling of power, the will to power, power itself in man. What is bad? All that proceeds from weakness. What is happiness? The feeling that power increases, that resistance is being overcome.... Not contentment, but more power! Not peace at any price, but war! Not virtue, but efficiency! ... The weak and the botched must perish: that is the first principle of our humanity. And they should be helped to perish! ... I am writing for the lords of the earth. You say that a good cause hallows even war? ... I tell you that a good war hallows every cause!'Barbarous? Ruthless? Unchristian? No doubt. But so is life itself. So is all progress worthy the name. Here at least is honesty to match the barbarity, and, what is more, courage, the willingness to face great hazards, the acceptance of defeat as well as victory.

Let's look at those words again: "Germany becomes Nietzsche; Nietzsche becomes Germany." "I do not advise you to compromise and make peace, but to conquer." "The weak and the botched must perish...And they should be helped to perish!" This was Mencken’s personal credo. Reading these words, I have to say they sound like the credo of a madman. It might be urged, however, that Mencken was a youthful 34 when he wrote that essay, and that there were other times in his life when he fearlessly defended the weak. Could he have undergone a dramatic change of heart in later life?

The answer, based on Mencken's own writings, is a firm and unequivocal No. Some of the most damning evidence comes from a book repeatedly cited by Professor Coyne in his recent posts: Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1956). The book, which was written around 1945 (shortly after World War II) and published in the final year of Mencken’s life, and could therefore be said to represents his mature thinking. The quotes from Mencken listed below, most of which are taken from this book, demonstrate that right up until the end of his life, Mencken held ethical views which were deeply repellent, and can fairly be described as Nietzschean.

As for Mencken's defense of the weak: I think it is reasonable to suggest that the individuals Mencken defended were precisely those who (he thought) were being unfairly hobbled by their intellectual inferiors, and because the way they were being killed by their oppressors violated Mencken’s sense of fair play. Having a sense of fair play, however, is perfectly consistent with adhering to a Nietzschean ethic.

Hitchens was also puzzled (see here and here) by the insensitivity displayed in Mencken's review of Hitler's Mein Kampf in The American Mercury (December 1933) – a review which, says Hitchens, "gravely hurt his gentle and indulgent patron, Alfred Knopf." To be sure, Mencken expressed the hope on the last page of that review that the Germans would rise up and assassinate Hitler, but the review also contained a passage which suggested that the Jews were partly to blame for anti-Semitism in Germany and the rest of Europe. In Mencken’s own words:

His [Hitler's] anti-Semitism, which has shocked so many Americans, is certainly nothing to marvel over. Anti-Semitism is latent all over Western Europe, as it is in the United States, and whenever there are public turmoils and threats of public perils it tends to flare up, as it did in France in 1894, when the French feared a new Franco German war, and in Austria during the lunatic days following the war. The disadvantage of the Jew is that, to simple men, he always seems a kind of foreigner. He practises a religion that is not common, he has customs that seem strange to the general, and only too often he indulges imprudently in talk about going back to his own country some day, and reviving the power and glory of his forefathers. He is commonly a fierce patriot in whatever land he lives in, and he certainly was, at least in most cases, in Germany during the war, but his patriotism is always ameliorated, despite its excess, by a touch of international-mindedness born of his history, and in consequence he is commonly held suspect by patriots who can't see beyond their own frontiers. Thus he is an easy mark for demagogues when the common people are uneasy, and it is useful to find a goat. He has served as such a goat a hundred times in the past, and he will probably continue in the role, off and on, until his racial differentiation disappears or he actually goes back to his fatherland.

That was a staggeringly insensitive thing for Mencken to write, in 1933. It would be quite wrong to describe this passage as racist, and Hitchens does not do so; but it was certainly thoughtless.

One has to ask, therefore, why Professor Coyne would devote an entire week of posts to quoting from the writings of a man like Mencken – a man who should be quietly buried rather than praised.

The case against Mencken, from his later writings

I declared at the beginning of this post that the evidence I'm presenting here is political dynamite, and I'm not exaggerating. Of course, many other authors have previously covered much of the evidence I'm presenting here, but as far as I'm aware, no-one has done so in a systematic manner. What I've done in this post is to collect all of the evidence together and organize it by topic, so that readers can see the "big picture."

The following quotes represent a selection of the most damning remarks in Mencken's later writings, arranged thematically for ease of reference. Let the reader be warned: the quotes listed here will be very difficult for many readers to stomach. They contain remarks that are extremely offensive and may cause acute distress to many people, especially people of color. Later in this article, I shall provide extended quotations from Mencken's Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1956), in order to situate these remarks in their full context. I shall also provide additional quotes from Mencken's Minority Report and other writings, which flesh out the picture I'm providing here. All quotes will be fully documented. The evidence I provide below will (I hope) allow the reader to decide whether I have quoted Mencken fairly or not.

Without further ado, here are some brief quotes from Mencken's writings. They speak for themselves.

Mencken on black people

In any chance crowd of Southern Negroes one is bound to note individuals who resemble apes quite as much as they resemble Modern Man, and among the inferior tribes of Africa, say the Bushmen, they are predominant. The same thing is true of any chance crowd of Southern poor whites.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1956, Section 379.)

[The following three passages are taken from Mencken’s earlier writings on black people, written when he was 30, 33 and 46 years old, respectively. - VJT]

There are exceptional negroes of intelligence and ability, I am well aware, just as there are miraculous Russian Jews who do not live in filth; but the great bulk of the race is made up of inefficients.

(Men versus the Man: A Correspondence between Robert Rives La Monte, Socialist, and H.L. Mencken, Individualist, 1910, p. 162.)

I am far from a Southerner in prejudice and sympathies, though born on the borders of the South, but it seems to me that, so long as we refrain, in the case of the negro loafer, from the measures of extermination we have adopted in the case of parasites further down the scale, we are being amply and even excessively faithful to an ethical ideal which makes constant war upon expediency and common sense.

(Men versus the Man: A Correspondence between Robert Rives La Monte, Socialist, and H.L. Mencken, Individualist, 1910, p. 163. Note: Despite the use of the very strong word "extermination" here, Mencken did not advocate any kind of violence against black people, at any time in his life. Indeed, he denounced such violence in his columns in The Baltimore Sun in the 1930s.)

The vast majority of people of their race [the black race – VJT] are but two or three inches removed from gorillas: it will be a sheer impossibility, for a long, long while, to interest them in anything above pork-chops and bootleg gin.

("The Aframerican: New Style", in The American Mercury, February 1926, pp. 254-255. These remarks of Mencken's formed part of a book review in which he praised the literary output of several black intellectuals, who had recently written a book of essays. Mencken's point was that he believed these individuals to be the exceptions to his rule.)

Mencken on Native Americans

The doctrine that there are actually differences between races is well supported by the case of the American Indians... [T]hey have not produced a single man of any genuine distinction in any field save military leadership, and even in that field, despite the opportunities thrown in their way, they have produced only a few... In brief, it has been found after long and costly experiment that the Indians cannot be brought into the American scheme of things. They apparently lack altogether the necessary potentialities. They differ from whites not only quantitatively but also qualitatively.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 378)

Mencken on the Jews

No Jewish composer has ever come within miles of Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, no Jew has ever challenged the top-flight painters of the world, and no Jewish scientist has ever equalled Newton, Darwin, Pasteur, or Mendel.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 407)

Mencken on poor Southern whites

If all the farmers in the Dust Bowl were shot tomorrow, and all the share-croppers in the South burned at the stake, every decent American would be better off, and not a soul would miss a meal.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 377)

If all the inhabitants of the Appalachian chain succumbed to some sudden pestilence tomorrow, the effect upon civilization would be but little more than that of the fall of a meteor into the Ross Sea or the jungles of the Amazon.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Section 50)

The immigration of thousands of Southern hillbillies and lintheads to Baltimore after 1941, set up by the new war plants, had at least one good effect: it convinced native Baltimoreans that the Southern poor white was a good deal worse than the Southern blackamoor... It was really shocking to Baltimore to discover that whites so thoroughly low-down existed in the country. They were filthier than anything the town had ever seen, and more ornery. The women, in particular, amazed it: they were so slatternly, so dirty and so shiftless that they seemed scarcely human.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Section 385)

Mencken on sterilizing people of inferior races

The great problem ahead of the United States is that of reducing the high differential birthrate of the inferior orders, for example, the hillbillies of Appalachia, the gimme farmers of the Middle West, the lintheads of the South, and the Negroes... The theory that inferior stocks often produce superior individuals is not supported by any known scientific facts. All of them run the other way.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 270)

Mencken on sterilizing poor people

Any man, having a child or children he can't support, who proceeds to have another should be sterilized at once.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 321)

Mencken on sterilizing criminals

The objection to sterilizing criminals is mainly theological, and hence irrational.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 6)

Mencken on capital punishment

Capital punishment has failed in America simply because it has never been tried. If all criminals of a plainly incurable sort were put to death tomorrow there would be enormously less crime in the next generation. England tried that scheme in the Eighteenth Century, and with great success.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 60)

If we had 2,000 executions a year in the United States instead of 130, there would be an immense improvement. I don't think that many innocent men would be in danger. Every one knows who the principal professional criminals are. In Germany Hitler rounded them up and beheaded them at once... The one certain, swift and cheap way to deal with them is to put them to death.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 64)

Capital punishment has probably been responsible for a good deal of human progress... [T]he overwhelming majority of those executed were of the sort whose departures for bliss eternal improved the average intelligence and decency of the race. They left the earth, to paraphrase the shrewd John Gay, for the earth's good.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Section 219)

The English hanged out their criminal class in the Eighteenth Century, and as a result England is the most orderly of all great countries today.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 262)

Mencken on suicide

I have known a good many men and women who took their own lives, but I can't think of one whose decision was illogical.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 106)

A fool who, after plain warning, persists in dosing himself with dangerous drugs should be free to do so, for his death is a benefit to the race in general.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 428)

Mencken on adultery

The prejudice against adultery arises from the inferior man's fear that he can't hold his woman. This fear, in the presence of competition from a better man, is certainly not without reason... It would be interesting to speculate about the debt civilization owes to the complaisance of married women. That complaisance has not only produced a great many able and valuable men, for a cross between the gentry and the folk is often superior to the average of either; it has also saved the lower levels from a reversion to savagery.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 9)

Mencken on homosexuals

A rational educational system would require all women who teach boys to be married... I incline to believe that men teachers should be married too, or at least that they should be persons of some worldly experience. They have enough inhibitions as it is, without adding those of sex. There is a very high percentage of homos among them... Our young are thus thrown into the hands of eunuchs, male and female.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 426)

The muscular Christian of whom so much is heard from time to time often turns out on examination to be a homosexual.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 227)

Mencken on the relative intelligence of Pentecostals and dogs

The belief that man is outfitted with an immortal soul, differing altogether from the engines which operate the lower animals, is ridiculously unjust to them. The difference between the smartest dog and the stupidest man - say a Tennessee Holy Roller - is really very small, and the difference between the decentest dog and the worst man is all in favor of the dog.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 414)

Mencken on healing the sick

As for a physician, he is one who spends his whole life trying to prolong the lives of persons whose deaths, in nine cases out of ten, would be a public benefit.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 181)

Mencken on the stupidity of the average man

Indeed, it may be said with some confidence that the average man never really thinks from end to end of his life… My guess is that well over eighty per cent of the human race goes through life without ever having a single original thought. That is to say, they never think anything that has not been thought before and by thousands.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 13)

Mencken on why smart people deserve a privileged existence, and why the rest of us are cockroaches

Every contribution to human progress on record has been made by some individual who differed sharply from the general, and was thus, almost ipso facto, superior to the general. Perhaps the palpably insane must be excepted here, but I can think of no others. Such exceptional individuals should be permitted, it seems to me, to enjoy every advantage that goes with their superiority, even when enjoying it deprives the general. They alone are of any significance to history. The rest are as negligible as the race of cockroaches, who have gone unchanged for a million years.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 344)

Mencken on American stupidity

The belief that man is immortal is a vestige of the childish egoism which once made him believe that the earth is the center of the solar system. This last is probably still cherished by four Americans out of five.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 144)

Mencken on the need for a world conqueror

Mankind has failed miserably in its effort to devise a rational system of government... My belief is that the nearest approach to a solution that is conceivable will have to be provided by something on the order of a world conqueror. If a really first-rate man got control of all Europe he could vastly improve the government of every country, and immensely diminish its cost. Unfortunately, such a man could achieve only a transient reform.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 201)

Mencken on the injustice of America’s entry into World War II

The United States got into both World War I and World War II by devices that would disgrace a gangster. Both times it made a foe by gross violations of elementary fair play, and both times its contribution to his overthrow consisted of stabbings in the back.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 353)

Mencken on the mildness of Soviet totalitarianism

In many ways Prohibition was more oppressive than anything ever seen in the totalitarian countries, or even in Russia.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 304)

To what extent, if any, was Darwin's theory of evolution responsible for Mencken's ethical views?

|

|

Charles Darwin and Ernst Haeckel. Images courtesy of Wikipedia.

There can be no doubt that Charles Darwin would have been appalled by Nietzsche's ethical philosophy, which Mencken eagerly espoused. Being a Darwinian evolutionist certainly does not make someone a Nietzschean.

Historically speaking, however, it is true that Nietzsche's philosophy could never have arisen without Darwin's Origin of Species, and was developed in response to Darwin's discoveries. Nietzsche first became aware of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection as a result of reading Friedrich Albert Lange's History of Materialism (1866). Its impact on the young Nietzsche was a dramatic one. As Richard Holbrooke narrates in Nietzsche: The Man and his philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 1965; revised 1999, pp. 72-73):

Darwin had shown that the higher animals and man could have evolved in just the way they did entirely by fortuitous variations in individuals. Natural selection was for Nietzsche essentially evolution freed from every metaphysical implication: before Darwin's simple but fundamental discovery it had been difficult to deny that the world seemed to be following some course laid down by a directing agency; after it, the necessity for such a directing agency disappeared, and what seemed to be order could be explained as random change. 'The total nature of the world,' Nietzsche wrote in Die frohliche Wissenschaft, 'is . . . to all eternity chaos' (FW 109), and this thought, basic to his philosophy, arose directly from his interpretation of Darwin.... Now God and man, as hitherto understood, no longer existed. The universe and the earth were without meaning. The sense that meaning had evaporated was what seemed to escape those who welcomed Darwin as a benefactor of mankind. Nietzsche considered that evolution presented a correct picture of the world, but that it was a disastrous picture. His philosophy was an attempt to produce a new world-picture which took Darwinism into account but was not nullified by it.

Nietzsche was certainly not a pure Darwinian. Indeed, in his Will to Power (paragraphs 684-685), he expressly rejected the sufficiency of Darwinian selection, and argued that superior specimens had to be carefully nurtured. (For an in-depth discussion of this point, I’d like to recommend a paper titled, Nietzsche’s Anti-Darwin by John S. Moore, which was presented to the 11th annual conference of the Friedrich Nietzsche Society, Emmanuel College Cambridge,8th September 2001.)

However, the term "Darwinian" can be understood in a narrow and a broad sense; and it is certainly true that Nietzsche owed an intellectual debt to Darwin for having (as he saw it) demolished the last traces of natural theology, thereby making atheism a much more defensible position. In his essay, Moore cites Lange's History of Materialism, which points out that with atheism tended to go egoism. Nietzsche's will to power is a doctrine of radical egoism.

It is certainly true that Charles Darwin himself was no egoist, basing his ethic on the Golden Rule. But once one accepts the claim that there are enormous inequalities among human beings, it is difficult to see how a Darwinist could avoid drawing elitist conclusions. Leaving the issue of race aside for a moment, it is an undeniable fact that within each race of human beings, some individuals are far more intelligent than others: Einstein could do far more with his brain than I ever could with mine. It is also a fact that some individuals are far more productive than others, a few of these individuals (I'm thinking here of entrepreneurs who are also philanthropists, such as Bill Gates and Warren Buffett) contribute much more to the betterment of the human species than the average person. What sense, one might ask, is there in the democratic principle of "one person, one vote" if human beings are fundamentally unequal? Aren't Nietzsche and H. L. Mencken right on this point? And why shouldn't the "cognitive elite" enjoy their perks, as Mencken thought they should, if they create and produce more of lasting benefit for the human race than their fellow human beings?

As I see it, the only adequate response to this line of argument is to deny the premise: human beings are not fundamentally unequal, after all. The intellectual differences between individuals are superficial: they merely reflect differences in their brains. My brain, however, is not who I am; it is simply a part of me. As the late Mortimer Adler was wont to remark: "You can’t think without your brain, but you don’t think with it." Thinking, defined as an act of pure understanding, is an immaterial operation of the soul. Our thoughts have an intrinsic meaning in their own right. Neural processes have no meaning in their own right; hence they cannot be identified with thoughts. (The Thomist philosopher Edward Feser elaborates on this argument here, here, here, here and here.) Nevertheless, the operation of the intellect presupposes the existence of sensory information from which it can abstract its concepts. In a human being, this information can only be collected and co-ordinated by the brain, which is why we are incapable of thought when our brains are severely damaged by disease or some other impairment. But it is perfectly conceivable that my brain could be "rewired" for greater efficiency of information processing, without altering who I am. Indeed, future surgeons may one day be able to accomplish just that: and if they can, then what we call "stupidity" would turn out to be a curable disease.

What follows from all this, then, is that the people Mencken despised as "stupid" were not essentially stupid (i.e. stupid by nature), but merely accidentally so. This is the insight preserved by the Judeo-Christian tradition, when it declares that we are all equal in the sight of God. Given that premise, democracy becomes the only form of government which is fully compatible with human dignity.

Mencken's views on race

Stephen Jay Gould wrote that human equality is a contingent fact of history - which is perfectly true, for those who espouse a materialist view of human nature. Unlike Gould, H. L. Mencken did not believe that all human beings are equal. He drew the conclusion that the strong should govern the weak. He believed that the vast majority of black people and Native Americans were mentally inferior, and he encouraged the sterilization of what he saw as "the stupidest" segments of the population. Even for his time, though, Mencken's views on race were rather extreme. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Turning now to Mencken's views on race: New Atheists may reasonably object that some of Mencken's views regarding evolution and race turned out to be factually incorrect, and that science has shown them to be so. Yes – but my point is that "turned out to be" is the operative phrase here. "Human equality," as the late Stephen Jay Gould used to often remind his readers, "is a contingent fact of history." That statement is certainly true, if you accept a materialist account of who we are, as Gould did. And on that account, it becomes difficult to see why Neanderthal man should be considered the equal of modern Homo sapiens, even if it turns out that all races of Homo sapiens alive today are roughly equal in their intellectual capacities. Would it have been murder, for instance, for a Cro-Magnon to kill a Neanderthal? Mencken, as we’ll see below, thought it wouldn't have been. To him, Neanderthals were no cleverer than smart dogs.

However, if you believe, as many religious people do, that each of us was created with an immortal soul made in the image of God, then you could argue that any intellectual inequalities which may exist between people, whether they be prehistoric or present-day people, are of no consequence in the ultimate scheme of things. A prehistoric human who was capable of grasping any abstract concept at all, as a rule to be followed, would therefore qualify as human, no matter how rudimentary his/her tools. Neanderthals, unlike dogs or gorillas, were certainly capable of long-term planning, as was Homo ergaster, 1.8 million years ago. It is less certain whether Homo habilis had this capacity, but there is every reason to expect that archaeologists will be able to answer this question in the foreseeable future, by examining his tools more carefully.

But Mencken was an atheist, and atheists don't believe in souls – unless of course they're Jains. An atheistic evolutionist, writing in the first half of the twentieth century, would have had to acknowledge that Mencken’s views on race were scientifically tenable – and he/she would have been very hard put to say why the ethical conclusions Mencken drew from those views were wrong. Certainly his belief that the different races of man had diverged from the apes at different times was a respectable one, propounded by scientists of the stature of Ernst Haeckel (who did much to popularize Darwin's work in Germany) and Henry Fairfield Osborn (President of the American Museum of Natural History from 1908 to 1933) in the United States. However, Charles Darwin himself held a very different view: in his work The Descent of Man (1871), Darwin argued for a common origin of all human beings on scientific grounds. An entire chapter of his The Descent of Man was devoted to refuting the arguments of the polygenists and providing evidence for the common ancestry for all races. Most scholars found Darwin’s arguments persuasive on this point. Wikipedia provides an excellent summary of the scientific debate at that time in its article on Polygenism.

I would, however, like to point out that Mencken’s views on the intellectual inferiority of black people were extreme, even for his time. As far as I am aware, Mencken never abandoned his repugnant view, which he expressed in 1926, that "The vast majority of people of their race are but two or three inches removed from gorillas," even as he praised the literary achievements of a talented minority of black intellectuals. ("The Aframerican: New Style", in The American Mercury, February 1926, p. 255.) By way of comparison, let the reader turn to H. G. Wells’ The Outline of History (Macmillan: New York, 1921). In Chapter XII, Wells engages in a scientific discussion of the races of mankind which is remarkable for its detachment and fairness. In Chapter VII, on page 46, Wells writes:

Some "anthropologists" have even indulged in a speculation whether mankind may not have a double or treble origin; the negro (sic) being descended from a gorilla-like ancestor, the Chinese from a chimpanzee-like ancestor, and so on. These are very fanciful ideas, to be mentioned only to be dismissed.

In religious circles, too, the belief that all races are equal in the sight of God was widespread in Mencken’s day, as a glance at the following article from the 1911 Catholic Encyclopedia will confirm. Despite the stereotypes, the article steers well clear of the racism espoused by Mencken.

Even if we examine the writings of scientists at that time who were racists, we find that they compared what they regarded the "lower" races to man’s ancestors, rather than to apes. The racist anthropologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, for instance, drew parallels between the brains of Australian Aborigines (whom he regarded as primitive) and Java man, or Homo erectus as he is now called. Osborn’s bizarre views are described in a 2011 article at Strange Science by Michon Scott.

The only scientist of note whose racist views came anywhere near to those of Mencken was Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919). Michon Scott describes Haeckel's racism in another article:

...[M]odern readers must recoil at his [Haeckel's] views of race. He hypothesized that humans comprised multiple species, perhaps evolved from an ancestor who had lived on a now submerged continent called Lemuria. Haeckel expected — and wasn't very upset by the idea — that the "superior" Germanic peoples would eventually drive out the "inferior" groups. He also gauged the intellectual abilities of contemporary Papuans, "Hottentots" and Aboriginal Australians as below those of horses, elephants and dogs. Looking at the title page of the 1868 edition of Naturliche Schopfungsgeschichte, which showed a diagram of human races and various apes, even Charles Lyell thought the Africans looked too simian. Embarrassed, Haeckel agreed.

Haeckel's ridiculous assertions do indeed sound like Mencken’s statement, cited above, that "the vast majority" of blacks were "but two or three inches removed from gorillas." But it is important to note that Haeckel's remarks were made in 1868 – some 58 years before Mencken’s racist assertion in 1926. By then, science had moved on from crudely equating humans’ intellectual abilities with those of other animals. Such an equation would have seemed anthropomorphic.

The case against Mencken, then, is a pretty strong one. Even when judged by the standards of his day, he held ethical views which were downright repellent. And as Christopher Hitchens correctly observed in the review I cited above, Mencken was "an antihumanist as much as an atheist."

It might be urged that Mencken’s racism is tempered by the fact that he despised white Anglo-Saxons too. But this would be to misunderstand Mencken’s racial thinking. Judging from what I have read of the man’s writings, Mencken seems to have ranked races according to three main criteria: their contribution to science and the arts; their ability to adapt quickly and learn new things; and their martial, warlike spirit. Germans (and especially Prussians) were at the top of Mencken's racial hierarchy, and he had a healthy respect for the Japanese too, on account of the rapidity with which they had picked up Western learning, and their newly acquired military prowess. The English, by contrast, appeared to be a rather lazy race, to Mencken: their cultural achievements were inferior to those of the Germans, and they were reluctant to do their own fighting, if they could avoid it. For this reason, he had a special loathing for what he regarded as the "pure Anglo-Saxons" of Appalachia, whom he despised as much as he did Southern blacks.

So on behalf of Christopher Hitchens, I would once again like to ask Professor Coyne: what prompted you to nominate H. L. Mencken as the First New Atheist? Why celebrate a man like that?

Six Ways in which Mencken differed from today's New Atheists

For all his faults, however, Mencken’s views on religious matters were much fairer and more reasonable than those of today's New Atheists. Mencken differed from them on six vital points.

First, Mencken utterly despised converts. Unlike today's New Atheists, who want everyone to give up religion, Mencken believed that a virtuous person should display constancy in his/her behavior. Mencken disliked conversion of any kind, precisely because it smacked of inconstancy. He even wrote: "When a reader writes in to say that some writing of mine has shown him the light and cured him of former errors I feel disgust for him, and never have anything to do with him if I can help it."

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 162)

Second, Mencken was reluctant to convert people to atheism, even writing: "The loss of faith, to many minds, involves a stupendous upset - indeed, that upset goes so far in some cases that it results in something hard to distinguish from temporary insanity... For this reason I have always been chary about attempting to shake religious faith. It seems to me that the gain to truth it involves is trivial when set beside the damage to the individual. To be sure, he is also improved, but he is almost wrecked in the process."

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 194)

Third, Mencken had a hearty dislike of fanaticism: for him, the culture of the civilized man is based on the maxim, "I am not too sure." For that reason, he praised religions which did not claim to know the will of God, declaring that "The most satisfying and ecstatic faith is almost purely agnostic." (“Damn! A Book of Calumny”, ch. XLII, “Quid Est Veritas”, p. 95. Philip Goodman Company, Third Printing, 1918.) The religions he condemned were those which claimed to know the will of God with certainty. For today's New Atheists, by contrast, the claims of all religions are demonstrably false. Deism is the only belief system which might conceivably be true.

Fourth, despite his admiration of Nietzsche, Mencken struggled all his life with the thought that there might be an afterlife, and perhaps even a Hell. In this respect, he differed vitally from today’s New Atheists, who seem to be 100% certain that this life is all there is.

Fifth, Mencken had a genuine appreciation of the appeal of religion (which he described as “a transcendental solace in the presence of the intolerable”) and of Christianity (which he said "organizes and gives a meaning to life"). He was happy for the plebs to believe it, if that was what they wanted. In this respect, Mencken was closer in outlook to Alain de Botton, author of Religion for Atheists, than to today's "New Atheists," who (sadly) appear to be incapable of perceiving anything beautiful in religion at all.

Finally, Mencken was generous about the benefits religion had brought to mankind, even though he rejected its claims: "There is a considerable plausibility in the argument that religion serves a useful purpose in the world."

It gives me no delight to chronicle the faults of a man whose satirical writings I can still enjoy. He had his serious shortcomings, but he had his virtues too: he was a reliable, dependable individual, a loyal friend, a faithful husband and fearless in confronting what he perceived as injustice. But he was no role model, even for atheists, and his writings on evolution and against religion are best forgotten. The right thing to do would be to simply bid him adieu: Requiescat in pace.

At this point, many of my readers will have decided that they have seen enough evidence to form their own opinion of the man. But the quotes I have listed above are just the tip of the iceberg. Those who would like to see Mencken’s quotes situated in their full context, along with dozens of other supporting quotes, are welcome to read on. I have also included a discussion and critical commentary on Mencken’s anti-religious arguments. The quotes below, most of which are taken from Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks (1956), are divided into six themes:

1. Mencken's racism.

2. Mencken's ethical views

3. Mencken's contempt for humanity, for the common man and for Americans

4. Mencken's political views

5. Mencken's anti-religious arguments

6. Six Ways in which Mencken differed from the New Atheists.

MENCKEN'S BIZARRE BELIEFS - THE BIG PICTURE

Ceramic Tile Tessellations in Marrakech, Morocco. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In the remainder of this essay, I'm going to present H. L. Mencken's racism, his ethical views, his contempt for humanity and for the common man, his political views and his religious views as an ensemble. My aim is to give my readers a sense of the "big picture." I want them to see how the various pieces of the jigsaw puzzle fit together, and make up their own minds about the man.

1. MENCKEN'S RACISM

(a) Mencken's racism was driven by his belief that the different races of man had diverged from the apes at different times in history

Background: Charles Darwin, in his work The Descent of Man (1871), argued that the human race was descended from a single stock – a view known as monogenism or monogenesis. Most evolutionists followed him in this regard; however, quite a few prominent scientists disagreed with Darwin, and held that the different races of humans had evolved independently, from separate species of apes, and that they had diverged from the apes at different times in history, making some human races more primitive than others. The German naturalist Ernst Haeckel was of this view, maintaining that Caucasoids were the most civilized race, and that Africans were savages. Likewise, the American anthropologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, in his The Origin and Evolution of Life (1916) claimed that blacks and whites both evolved from different primates. H. L. Mencken was of a similar view, arguing that "man emerged from the primordial apes in two or three or even four or five distinct races."

According to Mencken, all races are not equal. As a German-American, Mencken had a deep love for all things Teutonic. He despised Appalachians (who were of English blood) as "pure Anglo-Saxons", whom he regarded as inferior racial stock, when compared to the average American. Mencken also declared that Southern blacks and Southern poor whites are on average more ape-like than "the common run of Americans", and he denigrated the Kalahari Bushmen (known today as the San people) of Africa as an "inferior tribe." In his own words:

The theory that all the races of mankind have descended from one stock is whooped up assiduously by the prophets of egalitarianism, but there is really no support for it in the known facts. On the contrary, there is every evidence that man emerged from the primordial apes in two or three or even four or five distinct races, and that they survive more or less to this day, despite the wholesale intermingling that has gone on in civilized countries. In many of the isolated backwaters of Europe - and of America too, as Appalachia witnesses -the traces of Neanderthal Man are much more evident than those of Cro-Magnon Man, who was vastly his superior. In any chance crowd of Southern Negroes one is bound to note individuals who resemble apes quite as much as they resemble Modern Man, and among the inferior tribes of Africa, say the Bushmen, they are predominant. The same thing is true of any chance crowd of Southern poor whites. It offers individuals so plainly inferior to the common run of Americans that it is hard to imagine them descending wholly from the same stock.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 379)

And what was Mencken's opinion of Neanderthal man? As the following passage shows, he believed him to be no more intelligent than a smart dog. It follows that Mencken held that the San people of the Kalahari were not much better than dogs in their intelligence, and that quite a few Appalachians and Southern blacks were on the canine level, as well:

After all, the art of thinking must be a relatively recent acquirement. Certainly it was not possessed by Neanderthal man, at least in our sense. Neanderthal man undoubtedly had a brain, but its operations were comparable to those of a smart dog's rather than to those of an intelligent man's. It was not until skepticism arose in the world that genuine intelligence dawned. When that happened no one knows, but it was probably not more than ten thousand years ago.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 84)

Mencken also thought that racial prejudice made good sense, on many occasions:

What is commonly described as racial or religious prejudices is sometimes only a reasonable prudence. At the bottom of it there is nothing more wicked than a desire to prevent dominance by a strange and more or less hostile minority. This was true, certainly, of the old animosity to the Irish Catholics, and it is true again of much American anti-Semitism. In the South it is even true, at least to some extent, of the violent feeling against the Negro.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 184)

(b) Mencken's views on black people

W. E. Du Bois (1868-1963), the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard. Du Bois was also an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author and editor.

Although H. L. Mencken respected the accomplishments of African Americans like DuBois, he also declared that the vast majority of blacks were mentally just above gorillas.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Mencken believed that the vast majority of people of African descent were inherently inferior to the average American. He would be considered a 'scientific' racist by today's standards. Furthermore, he opposed efforts to remove African Americans from what he considered their natural state of servitude.

Mencken's stated views on black people in the 1910s

In 1910, Mencken engaged in a literary debate with a socialist named Robert Rives La Monte. In the course of their correspondence, Mencken spelt out very plainly his views on the inferiority of black people. He also made it quite clear that he rejected the Christian view that blacks and whites were equal in the sight of God, as well as the socialist view that the differences between blacks and whites were the result of environment rather than heredity:

I admit freely enough that, by careful breeding, supervision of environment and education, extending over many generations, it might be possible to make an appreciable improvement in the stock of the American negro, for example, but I must maintain that this enterprise would be a ridiculous waste of energy, for there is a high-caste white stock ready at hand, and it is inconceivable that the negro stock, however carefully it might be nurtured, could ever even remotely approach it. The educated negro of today is a failure, not because he meets insuperable difficulties in life, but because he is a negro. His brain is not fitted for the higher forms of mental effort; his ideals, no matter how laboriously he is trained and sheltered, remain those of the clown. He is, in brief, a low-caste man, to the manner born, and he will remain inert and inefficient until fifty generations of him have lived in civilization. And even then, the superior white race will be fifty generations ahead of him.

(Men versus the Man: A Correspondence between Robert Rives La Monte, Socialist, and H.L. Mencken, Individualist, 1910, p. 116.)

Here's another excerpt from the same correspondence:

The negro loafer is not a victim of restricted opportunity and oppression. There are schools for him, and there is work for him, and he disdains both. That his forty-odd years of freedom have given him too little opportunity to show his mettle is a mere theory of the chair. As a matter of fact, the negro, in the mass, seems to be going backward. The most complimentary thing that can be said of an individual of the race today is that he is as industrious and honest a man as his grandfather, who was a slave. There are exceptional negroes of intelligence and ability, I am well aware, just as there are miraculous Russian Jews who do not live in filth; but the great bulk of the race is made up of inefficients. In the biological phrase, the negro runs true to type. There are few variations, except downward. I have known, I should say, at least five hundred negroes in my time, and of all these not more than ten have displayed any inclination whatever to rise above their racial level. ...I am far from a Southerner in prejudice and sympathies, though born on the borders of the South, but it seems to me that, so long as we refrain, in the case of the negro loafer, from the measures of extermination we have adopted in the case of parasites further down the scale, we are being amply and even excessively faithful to an ethical ideal which makes constant war upon expediency and common sense.

(Men versus the Man: A Correspondence between Robert Rives La Monte, Socialist, and H.L. Mencken, Individualist, 1910, p. 162.)

To illustrate his belief in racial inequality, Mencken drew a striking literary contrast between a fictional black preacher named Jasper Johnson and the Caucasian whom he esteemed most: the evolutionist Thomas Henry Huxley:

As examples of these unlike things, I can do no better than mention Thomas Henry Huxley and a man whom we may call the Rev. Jasper Johnson... In every characteristic, instinct, habit, and quality which serves to differentiate any man from any ape, Huxley was more lavishly endowed, perhaps, than any other individual man that ever lived; but in Johnson these characteristics, instinct, habits, and qualities, when they appear at all, are so faint that it is well-nigh impossible to detect them. Huxley, in a word, was an intellectual colossus; while Johnson, intellectually, scarcely exists at all.According to the Christian seers, they will kneel before the throne of God side by side, and spend eternity as brothers. According to the Socialist seers, they are equally fitted to deal with the great problems of society and the state, equally worthy of ease, protection, and leisure, and equally entitled to have the aid of their fellow-men in the achievement of their ambitions.

I am unable, my dear La Monte, to grant this much. It seems to me, indeed, that the man who attempts to prove merely that Huxley and Johnson belong to the same order of living creatures has a staggering task ahead of him. The gap between them, I am convinced, is greater than that between Johnson and the anthropoid apes. Physically, true enough, there is probably only a difference in degree, but mentally there is an abysmal difference in kind. No conceivable course of training, however protracted, could convert Johnson into an imitation of Huxley. The one came into the world with certain inherited traits, certain invaluable forms of congenital efficiency, which the other can never hope to acquire.

(Men versus the Man: A Correspondence between Robert Rives La Monte, Socialist, and H.L. Mencken, Individualist , 1910, pp. 233-235.)

Note that in the above passage, Mencken specifically mentions the Christian belief that black and white people are spiritually equal, and then declares that he simply cannot believe such a notion.

In 1913, Mencken argued that most blacks were doomed to servitude, and that there was little point in educating them, as it would make them discontent with their lot:

. . . the negro, no matter how much he is educated, must remain, as a race, in a condition of subservience; that he must remain the inferior of the stronger and more intelligent white man so long as he retains racial differentiation. Therefore, the effort to educate him has awakened in his mind ambitions and aspirations which, in the very nature of things, must go unrealized, and so, while gaining nothing whatever materially, he has lost all his old contentment, peace of mind and happiness.

(The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche,1913, pp. 167-168)

Mencken's views on black people during the 1920s

Despite his racist views, Mencken believed that black and white people should be equal before the law, as is shown by the following passage from the introduction to his literary masterpiece, In Defense of Women:

For an American to question any of the articles of fundamental faith cherished by the majority is for him to run grave risks of social disaster. The old English offence of "imagining the King's death" has been formally revived by the American courts, and hundreds of men and women are in jail for committing it, and it has been so enormously extended that, in some parts of the country at least, it now embraces such remote acts as believing that the negroes should have equality before the law, and speaking the language of countries recently at war with the Republic, and conveying to a private friend a formula for making synthetic gin. All such toyings with illicit ideas are construed as attentats against democracy, which, in a sense, perhaps they are. For democracy is grounded upon so childish a complex of fallacies that they must be protected by a rigid system of taboos, else even half-wits would argue it to pieces. Its first concern must thus be to penalize the free play of ideas. In the United States this is not only its first concern, but also its last concern.

(In Defense of Women, Introduction, p. xi. New York: A. A. Knopf, Revised edition, 1922.)

In later years, Mencken partially modified his views of the intellectual capacities of African Americans, and came to recognize that some of them were every bit as talented as whites. In 1926, a collection of essays by black intellectuals, edited by a black author named Alain Locke was published under the title, The New Negro: An Interpretation (New York: Albert and Charles Boni). In his review of the book, Mencken declared himself to be greatly impressed by the authors of the essays:

The Negroes who contribute to this dignified and impressive volume (including Dr. du Bois himself) have very little to say about their race’s wrongs: their attention is all on its merits. They show no sign of being sorry that they are Negroes; they take a fierce sort of pride in it. For the first time one hears clearly the imposing doctrine that in more than one way, the Negro is superior to the white man...Well, where is the evidence to support that superb contumacy? I believe that a great deal of it is to be found between the covers of this very book… Here a Negro of a quite new sort comes upon the scene – a Negro full of easy grace and not at all flustered by good society. He discusses the problems of his people soberly, shrewdly and without heat. He rehearses their achievements in the arts, and compares it dispassionately with that of whites. He speculates upon their economic future with no more than a passing glance at the special difficulties which beset them. He makes frank acknowledgement of their weaknesses. He pokes fun at their follies. And all this he says with good manners and in sound and often eloquent English…

As I have said, go read the book. And, having read it, ask yourself this: could you imagine a posse of white Southerners doing anything so dignified, so dispassionate, so striking? I don’t mean, of course, Southerners who have cast off the Southern tradition; I mean Southerners who are still tenaciously of the South, and profess to speak for it whenever it comes into question. As one who knows the South better than most, and has had contact with most of its intellectuals, real and Confederate, I must say frankly that I can imagine no such thing. Here, indeed, the Negro challenges the white Southerner on a common ground, and beats him hands down.

("The Aframerican: New Style", in The American Mercury, February 1926, pp. 254-255.)

However, in the very same review, Mencken also made it clear that he still believed the vast majority of black people to be inferior to the average white, and little better than gorillas:

How far the gentlemen of dark complexion will get with their independence, now that they have declared it, I don’t know. There are serious difficulties in their way. The vast majority of people of their race are but two or three inches removed from gorillas: it will be a sheer impossibility, for a long, long while, to interest them in anything above pork-chops and bootleg gin.

("The Aframerican: New Style", in The American Mercury, February 1926, p. 255.)

Mencken takes a stand: his defense of Southern blacks in the 1930s

But there was another side to Mencken’s character: the man loathed racial injustice, and fought against it tooth and nail. In the 1930s, Mencken courageously denounced violence against blacks, even putting his safety at risk in the process. Mencken was particularly critical of the lack of press coverage given to the Maryland lynching of Matthew Williams, which took place on December 4, 1931.

In 1989, in accordance with his instructions, Alfred A. Knopf published Mencken's "secret diary" as The Diary of H. L. Mencken. Here is what Mencken noted in his diary about the lynching of Matthew Williams:

Not a single bigwig came forward in the emergency, though the whole town knew what was afoot. Any one of a score of such bigwigs might have halted the crime, if only by threatening to denounce its perpetrators, but none spoke. So Williams was duly hanged, burned and mutilated.

(Quoted in the Wikipedia biography of H. L. Mencken. From The Diary of H. L. Mencken, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1989.)

Almost alone among white journalists, Mencken vigorously denounced the lynching of African Americans in the 1930s, when writing for The Baltimore Sun. He wrote no less than ten critical columns in The Baltimore Sun about lynchings of black men on the Eastern shore of Maryland in 1931. The Eastern Shore, Mencken wrote, was being run by "its poor white trash" that still accepted "the brutish imbecilities" of the Ku Klux Klan. Mentally and morally, he said, "it has been sliding out of Maryland and into the orbit of Arkansas and Tennessee, Mississippi and the more flea-bitten half of Virginia." (The reader will recall that Mencken viewed Appalachians as inferior racial stock.)

Mencken also criticized "the cowardice" of some newspapers on the Eastern Shore for their failure to accurately report on the violence, singling out The Salisbury Times and The Cambridge Daily Banner as examples of "a degenerating process" that had been undermining the region for years. The Banner, Mencken said, had criticized the lynching "formally, but only formally." The Salisbury Times, he wrote, "went to the almost incredible length of dismissing the atrocity as a 'demonstration.'"

Shore residents were outraged. They canceled subscriptions to The Baltimore Sun, burned the paper, beat up newspaper deliverers, and boycotted Baltimore businesses. Mencken refused to apologize, even after he was warned that he might be lynched if he traveled to the Eastern Shore.

Mencken's racism in the 1940s

In 1940, Happy Days, the first volume of Mencken's autobiography, was published. In that book, Mencken wrote disparagingly of both African blacks and rural Southern whites, referring to them as "anthropoid blacks" and "mountain baboons" respectively. White author Hal Crowther frankly addresses Mencken's racism in his book, Gather At The River: Notes From The Post-millennial South (Louisiana State University Press, 2005, p. 148):

Yet it was my own tribe, the rural Anglo-Saxon, that he despised most venomously and to whom, in his most spirited moments, he scarcely granted full membership in the human race. There's a classic passage in [Mencken’s autobiography] "Happy Days," classic for the way it unites the redneck and the African-American, cringing together under Mencken's lash:

"... a great many anthropoid blacks from the South have come to town since the city dole began to rise above what they could hope to earn at home, and soon or late some effort may be made to chase them back. But if that time ever comes the uprising will probably be led, not by native Baltimoreans, but by the Anglo-Saxon baboons from the West Virginia mountains who have flocked in for the same reason, and are now competing with the blacks for the poorer sort of jobs."Isn't that refreshing? My people, the mountain baboons. The truth is that Mencken, in his beleaguered German-American chauvinism, so loathed the Anglo-Saxons on both sides of the Atlantic that he'd have exulted to see our Motherland overrun by the Kaiser—or even, at one point, by the Fuhrer—and Buckingham Palace converted to a Biergarten and Hofbrauhaus.

Right up to the end of his life, Mencken continued to hold a very dim view of racial intermarriage:

No Southerner, save an occasional fanatic like Lillian Smith, author of "Strange Fruit," has ever argued seriously that intermarriage between the races should be tolerated. Even in the North partisans who go so far are rare, and most of them are obvious psychopaths.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 187)

(c) Mencken's belief that Native Americans are an innately inferior race

Sequoyah was a Cherokee silversmith. In 1821 he completed his independent creation of a Cherokee syllabic alphabet, making reading and writing in Cherokee possible. This was the only time in recorded history that a member of a non-literate people independently created an effective writing system. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Native Americans were an inferior race, in Mencken's view:

The doctrine that there are actually differences between races is well supported by the case of the American Indians. For a century or more they had every opportunity to embrace and adorn the American Kultur, with free education for the ambitious and social security for all. Yet they have not produced a single man of any genuine distinction in any field save military leadership, and even in that field, despite the opportunities thrown in their way, they have produced only a few. The Negroes, during the same time, have shown a very definite capacity for progress, though their opportunities have been much less. A few whites with some admixture of Indian blood have come to prominence on the old frontier, especially in politics, but all of them have been predominantly white, not Indian. Perhaps the flowers of this flock have been Robert L. Owen and Will Rogers, neither of them, it must be manifest, a really first-rate man. The Carlisle Indian School, maintained from 1879 to about 1930 for the training of likely Indians, produced a once famous football eleven, but not a single graduate of even the slightest distinction. Large numbers of its graduates, after their expensive education at the taxpayers' expense, returned to their tribes and became blanket Indians. In 1930 the Indian Bureau, convinced that the experiment of trying to turn Indians into useful Americans was a failure, closed the school, and took to educating its charges on a new plan, more consonant with their limited capacities. In brief, it has been found after long and costly experiment that the Indians cannot be brought into the American scheme of things. They apparently lack altogether the necessary potentialities. They differ from whites not only quantitatively but also qualitatively.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 378)

(d) Mencken's contempt for the Jewish race

|

|

H. L. Mencken considered Einstein's theories about space and time to be no more scientific than phrenology. According to Mencken, Jews were incapable of first-rate scientific and accomplishments. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Even in his mature years, Mencken held that the Jews, while gifted, could never be first-rate thinkers or artists.

The Jewish theory that the Goyim [Gentiles - VJT] envy the superior ability of Jews is not borne out by the facts. Most Goyim, in fact, deny that the Jew is superior, and point in evidence to his failure to take the first prizes: he has to be content with the seconds. No Jewish composer has ever come within miles of Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, no Jew has ever challenged the top-flight painters of the world, and no Jewish scientist has ever equalled Newton, Darwin, Pasteur, or Mendel. In the latter bracket such apparent exceptions as Ehrlich, Freud and Einstein are only apparent. Ehrlich, in fact, contributed less to biochemical fact than to biochemical theory, and most of his theory was dubious. Freud was nine-tenths quack, and there is sound reason for believing that even Einstein will not hold up: in the long run his curved space may be classed with the psychosomatic bumps of Gall and Spurzheim. But whether this inferiority of the Jew is real or only a delusion, it must be manifest that it is generally accepted. The Goy does not, in fact, believe that the Jew is better than the non-Jew; the most he will admit is that the Jew is smarter at achieving worldly success. But this he ascribes to sharp practices, not to superior abilities.

(Minority Report: H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1956, Section 407)

Viewed from a contemporary perspective, Mencken's remarks are amusingly wide of the mark. Nobel Prizes have actually been awarded to over 800 individuals to date, of whom at least 20% were Jews, although Jews comprise only 0.2% of the world's population. The list of Jewish Nobel Laureates is here.

There are also a couple of passages in Mencken's earlier writings which can only be described as anti-Semitic, such as the following statement from Mencken's introduction to his translation of Nietzsche's The Anti-Christ: