I have searched the internet high & low - there just isn't much information on Keith Ferguson.

Here are a couple of articles published shortly after Keith's death. I have taken these from the Austin Chronicle in hopes that someone might read them & learn a little about this great & sadly overlooked bassist. Preston Hubbard has told me that Keith was one of the sweetest guys that ever lived. RIP Keith Ferguson.

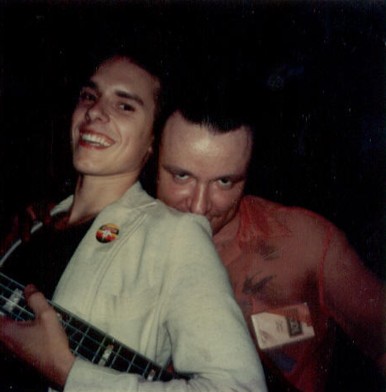

The postcard announcing Ferguson's 40th birthday Keith Ferguson's Legacy

Con Safos

by Dan Forte, c/s

Keith Ferguson died with a monkey on his back. I'm not speaking figuratively; the man literally died with a picture of a monkey on his back. It was tattooed there, the head of a fang-toothed baboon permanently inked into his shoulder. That was Keith Ferguson's statement to the world. So, when a friend called last week to tell me that Ferguson was in the hospital and probably wouldn't make it out alive, it didn't come as much of a surprise. Not to me, and probably not to Ferguson, either. The obituary in last week's Chronicle cited liver failure as the cause of death -- and that may indeed be what's on the death certificate -- but that's like jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge and having the resultant death termed a swimming accident. Liver failure was the cause of death in name only, because for 30 of his 50 years, Ferguson shot heroin.

True, for much of that time, he subsided on an exclusive diet of cigarettes and alcohol (specifically beer, typically Busch), and whether it was his liver that eventually called it quits, or his heart, or a leg badly infected from shooting up (the usable veins in his arms having long since collapsed), is irrelevant: Ferguson killed himself. The surprising thing about his death was that it hadn't happened years earlier.

Junkies die every day without meriting a paragraph, let alone a feature article, in the local newspaper. The reason you're reading about this particular junkie is that he also happened to be one of most talented and original musicians Texas has ever produced. That his music career took a back seat to his drinking and drugging career, especially in recent years, is a senseless waste of a human life.

The fact that behind the talent was an extremely intelligent and articulate person, one who could be generous, respectful, incredibly funny, and downright charming, makes that waste all the more colossal, not to mention inexcusable. At one time, Ferguson and I were good friends. When I moved to Austin in 1987, I lived upstairs in the converted attic of his house on South Second Street, and we spent many a 24-hour day together. But it had been several years since we last spoke, and when we'd cross paths in public there was an uncomfortable tension -- sometimes accompanied by an expressionless nod, if one of us forgot for a moment who wasn't speaking to whom.

The most recent and last such time our paths crossed was at the Carousel Lounge last summer. "See that guy?" I asked my wife, pointing across the room at a man who had once been fairly tall, but now seemed tiny. His once-handsome face was now gaunt, his skin a translucent, pasty gray covered with a layer of greasy sweat. His cool swagger was replaced by quick, nervous, in-need-of-a-fix gestures. "That's Keith Ferguson."

It wouldn't suprise me in the least if anyone who hadn't seen the bassist in his prime -- glimpsing instead the cartoonish character who played with undistinguished and indistinguishable blues bands on Sixth Street from time to time in recent years -- were as shocked as my wife upon first seeing Ferguson. "That's who you've been talking about?" Typical reaction, probably. Yet when I first saw Ferguson with the Fabulous Thunderbirds at Rome Inn in 1976, about a year after they'd formed, it was one of the most memorable musical experiences of my life.

Not quite 30, Ferguson was the oldest member of the band, yet he, like the rest of them, played the blues like a grown man -- and they sure as hell didn't sound like a bunch of "white kids." Still a decade away from commercial success (there were about 25 disinterested patrons at Rome Inn that night), Ferguson, Kim Wilson, Jimmie Vaughan, and the soon-to-join Mike Buck already showcased the indelible influence they would have on blues bands coast to coast and around the world. Collectively and individually, the original T-Birds sired cults and mini-cults, changing the way musicians played, dressed, stood, combed their hair.

At the center of all this was Ferguson, a unique, colorful, even charismatic persona, but that was just the icing on the mystique. At its core was one simple truth: He was as good a blues bass player as there was in the history of blues bass players. Even in capable hands, the subtle art of blues bass can be the musical equivalent of the witness protection program, yet Ferguson carved out a singular niche without ever saying "look at me" with his instrument.

"A roar in the right key" is how he described his unorthodox philosophy when I interviewed him for a 1986 Guitar Player magazine article on the Tailgators, the swamp-rock trio he joined after leaving the Thunderbirds. "I believe a bass player ought to be heard," he elaborated, "but not listened to. Unless you're into, `Man, did you hear that line?' You do that with a band that's playing Jimmy Reed and shuffles, and there's something seriously wrong with you. You can talk about virtuosity all you want, but what it comes down to is you're supposed to back up the other guys. They're not supposed to notice you until you stop."

Just as his playing had an incalculable impact on countless bassists, his look and personality spawned a legion of tattooed, leopard-shoed clones, who elevated him to a guru of sorts. (It might be years before some of these junior Fergusons can put on a shirt without wondering if it would pass the Keith test.) He sometimes got a kick out of seeing just how far these cult members would go to get his stamp of approval, like the time he urged Anson Funderburgh's bassist to paint his '58 Fender Precision aqua-marine metal-flake. "It was the same color as this house," he smiled sarcastically, "only metal-flake -- like a Mexican gang's dream."

There were three things things Ferguson rarely did: eat, sleep, or sit down. He paced constantly, and when he did nod off, it was often standing up. I'd sit there taking silent bets with myself on which would succumb to gravity first: his back, which could bend back farther than a limbo champion's, or the three-inch ash on his cigarette.

When I first moved in, Ferguson would close the door to the kitchen when he needed a fix. He knew that I knew he was a junkie, it just wasn't something we talked about. I could see the results; I had no morbid curiosity in viewing the process. But if you're around an addict 24 hours a day, at some point they're going to have to shoot up, so inevitably we'd be in the kitchen talking and Ferguson would feel (and fulfill) the need. There were no slow-motion, Pulp Fiction closeups of needle puncturing skin, and his eyes didn't roll back as he drifted off to dreamland; this was purely maintenance. It was about as romantic or glamorous as watching someone take a dump.

Over the course of any given all-nighter, he would go through every mood swing imaginable -- animated and energized one minute, dull and morose the next. And night after night, I was the one-man audience to a one-man show that rivalled anything you'd see on Broadway. Eric Bogosian on his best night had nothing on this kitchen monologist, as he documented and created characters, complete with dead-on voices, accents, and mannerisms. I half-seriously entertained the idea of wiring the kitchen so I could record him in action. The stories were fascinating, but it was Ferguson's "stage presence" that made you wonder if he'd missed his true calling.

Long after dawn, I'd pack it in and head upstairs, still hearing the bassist pacing downstairs. I'd wake up around commute time, head downstairs in my bathrobe, and find Ferguson sitting (finally) on the porch in his robe, sipping a Busch. I'd get one out of the refrigerator, and we'd watch the "squares," as he called them, drive to work. Ferguson especially got a laugh out of the days when we'd still be sitting there in our robes, beers in hand, when the same nine-to-fivers drove by in the opposite direction, heading home.

Ferguson was very knowledgeable and well-read, having no patience for ignorance, and yet he surrounded himself with parasites several evolutionary levels beneath him (otherwise known as drug dealers). He attached a lot of pride and sentiment to his friendships with famed musicians, but would pawn gifts they sent him for drug money: in Billy Gibbons' case, this included a custom-made, metallic red "gator" bass. He proudly displayed the hand-written letter Stevie Ray Vaughan had sent him from a rehab clinic in 1986 -- on the refrigerator, just a few feet from the kitchen table where he'd tie off and shoot up.

In his lifetime, Ferguson saw countless friends meet drug and/or alcohol-related deaths. He saw others clean up, but viewed them as wusses, as though they'd sold out to the squares, unable to tough it out or some such -- even though he was a grown man in his forties whose rent and phone were subsidized by his grandmother, his beer and cigarettes comped by friends.

Keith Ferguson was the most bitter man I ever met and had the least reason to be. Although he was gifted with talent, brains, looks, and some of the most loyal friends I've ever witnessed, he had a persecution complex the size of his drug habit and blamed the world for the life he had chosen. Nevertheless, in all the nights I stayed up listening to him curse the gods, I never saw anyone else tie off his arm with a dirty stocking. I never saw anyone else cook the dope and draw it into the syringe. I never saw anyone but him shoot heroin into his arm. He was solely responsible for squandering and ultimately ending the most precious of all gifts: a human life.

In the week since Keith's passing, I've alternately been torn between bitterness and sentiment, disgust and sadness. I've looked at pictures, listened to his music, played back tapes of interviews with him, and found an autograph he gave me nearly 20 years ago. Under his name he wrote "c/s." "That stands for con safos," he said, "like, `There to stay.'" That best describes my memories of Keith Ferguson. He's someone I'll remember for the rest of my life.

part two:

Keith Ferguson: No Apologies, No Regrets

Beautiful Loser

by Josh Alan Friedman

This story originally appeared in the Dallas Observer dated March 28, 1996.

"I have to admit, there's a guaranteed future in dirty dishes, which there ain't in blues," concedes Keith Ferguson. "I seem to be the only one who regards himself as a professional musician. Our lead singer's a dishwasher in the back of some restaurant. If he put half the energy into booking our band that he puts into scrubbin' dishes, we'd be fartin' through silk. But he'd rather do dishes."

Ferguson, Austin's once-reigning blues bassist and ultimate hipster, is out to pasture. His pasture is a rustic wooded estate in the hills below downtown Austin. His voice is a dead ringer for that of William Holden narrating Sunset Boulevard.

Some wonder whether Ferguson's fall from grace was conspiratorial, orchestrated by the blues Nazis who run Austin. But prison wisdom dictates that you don't fuck with an old wolf. Hear Ye Whomever Keith Has Offended: The man offers no apologies or regrets.

He welcomes me to his front porch, the center of his universe. His current band is the Solid Senders. Fronted by the singing dishwasher, they rarely work, particularly since Ferguson will only play cities south of Austin -- or Amsterdam. With its sane drug laws and hardly any cops, crime, poverty, or AIDS, Amsterdam is a tailor-made utopia. The Solid Senders did a blissful tour there. Ferguson pines to return: "If I hustled up some job washing dishes in Amsterdam -- hell, I'll supply the Palmolive -- we'd be back in a shot."

Ferguson, 49, was the founding bass player of both the Fabulous Thunderbirds and the Tail Gators, and played with a dozen Texas virtuosos in their formative years including Johnny Winter, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Junior Brown. "He's a cracker's cracker," Ferguson says of his old boss Brown. "Thinks that Waylon and them are commie fags." Ferguson keeps a band honest. When he departed the T-Birds, that band was ready to compromise and play the pop charts; he'd have none of it.

No bass player ever layered so much bottom. Ferguson's trademark wasn't licks, riffs, slapping, or thumb popping -- just a swinging elephant trunk of bottom beneath every song. This deceptive gift earned him a lower pedigree than "musician's musician," itself a poverty-stricken but honorable curse: Ferguson is a bass player's bassist.

Now, however, he's host of this dark, sun-proofed crash pad and halfway house for down-on-their-luck friends. Sweet old hippies and beautiful losers recline on his front porch to chew the fat, bird watch, and discuss the weather. Not that he wants them here; people sort of just move right in. Many who visit this front porch, be they from the dust bowl, barrio, or music biz, regard Ferguson as Numero Uno.

Inside, walls are covered by roadside artifacts -- South-of-the-Border Sammy and the Fabulous Erections are sneaking across the border for One Night Only -- club posters from the Tex-Mex frontier circuit: Los Alegres de Teran! Los Tornados del Norte! Los Castigadores! Ferguson knew them all. His words contain accents of Calo -- street language of the pachucos he grew up with, a sort of Mexican Yiddish.

A few years back, the house became knee-deep in such hipster compost, burying him alive in coolness. Live-in archivist Liz Henry led a mercy mission of volunteers that bulldozed through, organizing Ferguson's worldly possessions into three archival categories: "Negro," "Mexican," and "Other." Ferguson whips out his huge vintage Gretsch bass. "It's called the John Holmes model," he explains. "It's loud." He's healthy, proud, and fit in 1996, but reduced to playing the meat-rack clubs on Sixth Street. Still, some consider this miraculous. A few years ago, cats in Austin were predicting the end of this man's career, even his death.

Flashback: 1992

Ferguson paces his pastoral porch, hunched backward, scratching, chain-smoking, downing one cup of Kool Aid after another, looking like an old Indian. His body ails, and his tattoos have worn out their camouflage. A rooster claw adorns the front door, like wolfsbane. "Gotta keep the neighbors pacified." Next door lives a bookie for cock fights; a few doors down, an unlicensed bad-debt collector. A Mexican Day of the Dead skeleton stares through his window, with a sign: "La Plaza -- Closed -- Call Again."

The Ferguson estate is verboten, like Castle Dracula, as few musicians in Austin will have anything to do with him. I make this road stop after my gig in town. A festive trio of German blues fans have also made a pilgrimage, but no music plays in this household. Ferguson's basses are all in the hockshop. Horst, Otto, and Gretchen are star-struck before Texas blues royalty, as Ferguson signs a few T-Birds albums. The left-handed '52 Fender Precision bass that Europeans remember him by is long gone. He's a normal 180 pounds on the Chrysalis album covers he signs, 130 now.

Ferguson soberly inspects the festering tattooed arm of a young Chicano nodding out on the couch. "Gotta clean out that abscess," he advises, shaking the fellow. "You can die." Old hombres, in tank-top undershirts, are always present. They slink in and out, from another zone. Retired bullfighters, Ferguson tells the tourists. The old men study a black phone. They sit and wait. And watch. Then the phone rings once. Ferguson disappears with them in a supernatural eye-blink. No one says goodbye, ever. Musicians avoid the Ferguson ranch for fear of having their cars commandeered for a barrio run.

During one visit, it's my job to drive Ferguson to some urgent destination. Though banished from the Antone's blues community, Ferguson is highly received in the Mexican ghetto like some kind of shaman. He was raised in the Sexto, or Sixth Ward, a barrio of Houston -- the odd Anglo in a Mexican gang back in San Jacinto High, class of '64. Our ride, through dusty roads, conjures up childhood. Summers were spent with his grandmother in San Antonio, totally gaucho.

"It was great in the Fifties, pre-Beatles, before everybody had bands," he says. "There were only about eight bands in the whole area: Doug Sahm and the Pharaohs, Sammy Jay and the Tiffanaires, Eddie Luna. You had Mexicans, blacks, and whites in the same band, which was unheard of." Electric guitars were rare and exotic sights until the mid-Sixties. "I remember hearing Dino, Desi, & Billy do `Scratch My Back' on Shindig. Good, too. I was one of two left-handed bass players in all of Houston when I started in 1966, at the age of 20." Few musicians start so late.

In high school, Ferguson had been tight with the best mariachis in town, heavy-duty lounge acts. A member of the Compians, Houston's leading Hispanic entertainment family, taught him to play. Ferguson turned professional mere days after first picking up a bass. He worked the Suburban Lounge, the Polka Dot, Guys & Dolls -- Houston blue-collar joints, frequented by characters from the Overton Gang and the Laura Coppe Gang.

"They would rob places," he says. "They dressed like Mexicans, listened to black music, and hated both of 'em." Where was your father? I ask as Ferguson directs me off the main road through dirt alleys. "My father was a bum," he shrugs. "I hated him with a passion. He didn't live with us. I never saw him growing up. But he would be called whenever I was deemed unmanageable -- hangin' out with someone with a natural tan. My mother would panic: `You've got to talk to him, John!'

"Once when I was 15, I was supposed to get a haircut but didn't. When he arrived, I asked him to get the hell out. He pulled me out of a chair by my hair. So I cut him with a metal rat-tail comb, the one with the end bent into a hook. Then I tried to get to my room for something better -- my big Italian, spiked, carbon-steel switchblade. He managed to knock me out before I reached my room. My mother was shaking me, blubbering all over me when I awoke. It was a nasty scene. I'd cut him in the throat, but unfortunately missed the carotid artery. I was a little off."

photograph by Lone Star Silver

No bass player ever layered so much bottom. Ferguson's trademark wasn't licks, riffs, slapping, or thumb popping -- just a swinging elephant trunk of bottom beneath every song.

Ferguson escaped from his bedroom window that day to gang quarters over an ice house, a place where Mando, Mario, Ladislado, Alfonso, and Parrot could crash, drink, smoke, and inhale paint. "The side of my face was bent out of shape when I showed up. They decided to kill him. I had to talk fast. He was my father. I said, `He didn't really come to discipline me. Don't kill somebody for that,' 'cause they would have been caught in a second. My father was a white guy. They wouldn't have stood a chance.

"They drafted the guys with a gang history out of my school into the Marines. The other option was jail. They were perfect cannon fodder, 'cause it was the ideal chance for them to become Americans if they fought for their country. But they came back with one leg and were still Mexicans. Most of `em got killed in the war. Idiots."

Ferguson was destined for Mexico, his spiritual homeland, not Canada, to evade the draft during Vietnam. A week before his draft-board physical, he tore the cartilage in his knee during a fight in Laredo. He got his deferment.

It wasn't until his mid-twenties that Ferguson found out who his father was: John William Ferguson, concert pianist with the Chicago Symphony. He never even knew his father was a musician. "You ass-wipe," he told the maestro during their next encounter. "I've been beat, ripped off a thousand times playin' clubs. There's so much you could have taught me." After the Thunderbirds tore up the Houston Juneteenth Festival, being the only white band there, they received a four-page spread in the Houston Post. From then on, the elder Ferguson began showing up at Thunderbirds gigs.

"He would point me out to his friends: `My son, the rock star,'" recalls Ferguson. "He picked up girls at our shows. Johnny Winter and Z.Z. Top sent their limos for him to attend concerts. After I left the T-Birds, I never heard from him again." John Ferguson died a few years ago. His son directs my car through the barrio.

Somewhere in these hills beneath Austin remain the last of the old pachucos, time-honored Mexican families who dealt heroin to Texas Hill Country junkies for decades in relative peace, until the era of crack arrived. The old-timers were overwhelmed, their quaint Norman Rockwell-era heroin days over. Colombians moved in with machine guns. Ferguson describes the current transitional wars, directing me through a Mexican shantytown.

We finally reach a tin shack. Ferguson has been summoned to visit an old friend's dying boy. At least that's what I'm told as I wait outside in a spanking-new white Honda Accord. Sure enough, 15 minutes later, Ferguson emerges. A worried madre and padre follow, gratefully embracing him for paying his respects. This is Texas, not Mexico. I ask why the boy wasn't in a hospital. "They prefer their own medicina," he says.

Back in Time

"This is about the only thing my dad gave me as a kid that I saved." Back on the front porch, Ferguson shows me a cherished, yellowed 1945 paperback by madcap cartoonist VIP. "This and a few old records. People would kid me about my large collection of blues records. That's all I listened to -- I was fanatic -- that and Mexican stuff. Like in sixth grade, people would bring 45s to parties, but they never wanted me to bring my Otis Rush or John Lee Hooker records."

Johnny Winter moved from Beaumont to Houston when Ferguson was in high school. "Since blues was all Johnny liked, these local musicians thought it would be hysterical if we got together: `Let's put these two freaks, these two mutants together.' Johnny flipped out. He never saw that many 78s in his life. He had records, too, but I had more."

Ferguson began backing Winter at small lesbian bars like Club L'mour. Ferguson was dazzled by Winter's virtuosity -- it was "alarming," he says now -- and often had to tell himself not to stop and stare at his playing during the middle of a song. "We used to call him The Stork," Ferguson says. "Nobody messed with him. One night he knocked out an off-duty cop for callin' him a girl. I saw Johnny Winter fight many times, he was real strong and mean. He'd go until you quit breathing and couldn't hurt him anymore."

Ferguson made Austin his home in 1972, after his stint with Winter had ended. He moved because the aggressive Houston Police made him uncomfortable -- and he wanted into the Storm, Jimmie Vaughan's old band. After a brief stint, he joined up instead with Stevie Ray Vaughan and Doyle Bramhall. "Nobody wanted to hear us," Ferguson recalls. "Nobody."

In 1975, Kim Wilson left Minnesota to play with Jimmie, and Ferguson rejoined Storm. "We couldn't get arrested either, but we were doin' a helluva lot better than me and Stevie and Doyle did locally. It was the `Cosmic Cowboy, Willie-Waylon-and-the-Boys' outlaw town then, but we were the outlaws. People wondered how we survived: `Well, they never work.' We were so hard-core [blues], nobody knew what to do with us. But Antone's came along, sort of saved us. At least we could get some food. They served lots of poboy sandwiches.

"Muddy Waters heard us at Antone's. We fried him. We were told we sounded like his best band from the Fifties, with Jimmy Rogers. We weren't trying to. It was innate. He went back North ravin' about us, and Jimmie started gettin' calls. So we got in our little van from Austin to Boston, nowhere in between. We started openin' for [Kansas City jump-blues revivalists] Roomful of Blues. Then it got to where they were openin' for us. People seemed astonished by us."

The Fabulous Thunderbirds were the first white blues group that didn't look and play like hippies. The T-Birds took it back 20 years. Jimmie Vaughan exorcised all the rock-guitar innovations -- as if Beck, Hendrix, Clapton, Winter, and Bloomfield never existed -- and threw it back to a long-abandoned, spare, Fifties Chicago groove, more authentic than early Stones. Countless guitarists took heed.

Kim Wilson applied no fake rasp to his voice, no black affectations, no phonetic imitations of slurred words. He sang it straight. The Fabulous Thunderbirds spearheaded a re-animation that stabilized the course of blues, spawning back-to-basics bands that proliferate to this day. Blues cognoscenti even began to emulate Jimmie Vaughan's slicked-back hair and open-collar, Fifties rayon shirts, newly designed and imported from India by Trash & Vaudeville in the East Village. Ferguson's transparent camisas tripled in price at Austin clothing stores. "That's just the way we dressed in high school," Ferguson says. "The fashion of pachucos and thugs who've long since died -- or gone double-knit.

"Pretty soon everyone up in Boston wanted to be us," Ferguson recalls. "We still couldn't get arrested here in Austin, but we went from floors to motels in Boston. Everyone in the band but me wanted to move to Boston. They followed the record company line: `You guys are fine, but all you have to do is change.' They think blues is a stone to step on to get somewhere else. You'll notice each one of our records got more expensive to make -- and more diluted, as far as I'm concerned. I thought we should have held out for an art subsidy, 'cause there wasn't anybody else out there doin' it except Roomful of Blues. But we were more primitive, playing like skeletons."

"Muddy Waters heard us at Antone's. We fried him." photograph by Watt Casey

Tuff-chick/hick blues shouter Lou Ann Barton was in the T-Birds for a spell. She even married Ferguson in Rhode Island, though their union lasted only a short while. "She told people she and I could be happy in a pile of shit," Ferguson says. "She kept a good house for a white girl her age. Since I was always gone, and she was fixin' to be, marriage would give us some sort of stability. But it worked just the opposite, blew us apart."

It's whispered that the T-Birds were the only white blues band that intimidated the Stones, for whom they opened twice at the Dallas Cotton Bowl and twice at the Houston Astrodome during the 1981 tour. Pussy flowed, perhaps more abundantly than for any mere blues group ever. "I'm the only one in the band who actually talked with girls, too," he says.

Ferguson played bass on the first four Thunderbirds albums -- the essential ones -- as well as on the Havana Moon collaboration with Santana. He was fired in the mid-Eighties, about the period when the Thunderbirds switched to CBS Records and began scoring on Top 40. Ferguson leveled a lawsuit at the T-Birds claiming owed money, refused to settle, and was trounced in court. For many years, there was acrimony and scorched earth.

The Fabulous Thunderbirds spearheaded a re-animation that stabilized the course of blues, spawning back-to-basics bands that proliferate to this day.

Jimmie Vaughan and Kim Wilson would not discuss Ferguson for this article. Clifford Antone says nothing for the record, other than swearing, "Jimmie Vaughan and Kim Wilson never did anything to hurt him. You can't guess at this. It's too deep. Don't even try." Perhaps he was too bluesy, too primitive, too tattooed -- The Illustrated Man, The Man With the Golden Arm -- or couldn't cross borders. Maybe he got so hip, he just hipped himself right off the planet.

Yet there were knock-down, drag-out, shit-kicking fist-fights between Ferguson and Wilson -- the distinguished, sharply dressed ambassadors of the blues. "They wanted somebody else," shrugs Ferguson. "That's what [Jimmie Vaughan] told me. Just wanted to do somethin' new. So I went lookin' for other work. I found it. Anyway, I quit drinkin' liquor when I left the T-Birds, and lost 50 pounds," he claims, as if that fact made the departure a good health move. But it was 50 pounds he needed.

Another Day in Paradise

The legendary out-of-work bass player arises another day to click on Real Stories of the Highway Patrol. Commissioner Maury Hannigan, our host, represents The Man -- every man empowered to break Ferguson's balls. This fatherly, mature voice of law enforcement embodies everything that's ever kept Ferguson down: a sprinkle of absent and abusive father, perhaps a dash of Sixties draft board, a few shakes of burr-headed gym coach, the customs officers who make Ferguson miss planes, the Austin cops who ticket local musicians unloading amps on Sixth Street, narcs who've interrogated and beaten him, who couldn't give a shit how many landmark albums he played bass on. They all form a composite of this brown-uniformed, hair-dyed, show-biz cop.

"Look, they're on a roll," observes Ferguson, as state troopers hunt down some truckdriver's roach. The next segment has New York's Finest surrounding a maniac, about to toss the Net -- a humane method to capture PCP freaks. Ferguson sits transfixed as the maniac flails, rendered helpless. "That's nothin'," comes one of Ferguson's roadside cronies. "They got a blanket called the Wrap for smelly winos, so's not to befoul the back of the squad car."

Commissioner Hannigan is back on the screen with contempt for everything Ferguson stands for: the 17 lizard tattoos snaking up and down his right arm, his glistening "We-don't-need-no-steenking-badges" gold tooth, his born-cynical sneer. Such cops were put on earth to make life miserable for Ferguson, a once studly rock star who now resembles a withering Aztec Indian, a poster boy of ethnic suspicion. Avoiding the Highway Patrol is one reason he doesn't drive. You want the legendary Ferguson on your gig, you gotta come fetch him.

The Classic Thunderbirds: Jimmie Vaughan, Kim Wilson, Fran Christina, and Keith Ferguson

"I was drivin' alone in 1970, and this big voice came outta nowhere and said, `When you get to where your goin', you need to quit, or you're gonna die,'" he recounts. Don't cop shows give you nightmares?, I wonder. "No. We get stopped, pulled over, and humiliated for real." Ferguson was jailed en route to a gig with the Excellos several blues bands ago. He had moved a roadblock on Sixth Street to avoid a construction detour in front of the club.

"Cops were staked out there, waiting to fight crime. They fucked with me the whole ride to the station about how I look. Textbook Batman and Robin pigology: Some little booger half my age, heavily armed, baiting me while I'm handcuffed, tells his partner, `Would you mind takin' this down to the station?' Then he tells me, `I don't know why you're pissed off. You're makin' $700 a night.' He thought it was a riot I only had 16 cents." I ask him if he's picked up any tips from our host, Hannigan. "Yeah," he responds. "Move, leave the country."

On another day's visit, I drop by the porch with New York rock diva Phoebe Legere. She straps on her "squeezey-gut" accordion, about to launch into "La Vie En Rose." Ferguson lies in a hammock. Sweet Liz Henry, who organized his house, is slumbering on the couch. Others lie across the porch in various zones of consciousness. Il ne parle tous bas.

"Je vois la vie en rose," sings Legere.

Ferguson opens one eye. Then the next.

"Oh, I like your smile," says Legere.

"Cost me $200," Ferguson answers.

At the very last note of the waltz, absolutely on cue, the transformer near the top of a tree that intersects the roof begins to explode. Showers of sparks rain down on the porch. Hippies scurry from all points through the front door. Sweet Liz and Ferguson offer permanent residence to Legere. Some other fellow eyes the squeezey-gut, perhaps wondering how much it might fetch downtown at Rockinghorse Pawn.

Ethnic musicians have a tendency to serenade Ferguson, if only to watch his spectacular, gold-toothed smile. When the Tail Gators toured with Los Lobos, there was the unforgettable image of that band from East L.A. circled 'round Ferguson's hotel mattress one evening to awaken him for the stage. Each had their conjunto instruments -- the bajo sexto, the guitarron -- mariachis harmonizing in Ferguson's beloved Spanish. It's been a few years since Ferguson sojourned to the guitar-making town of Paracho, in the pine-forest mountains of Michoac�n.

"I never had any trouble with Mexican customs, but America's convinced everyone's bringin' back tons of dope," says Ferguson, offering one more reason he now shuns touring. "Don't ever say you have a plane to catch. Believe me. You might as well just arrest yourself. When I came back on Christmas through Houston, I brought a custom-built bass. They took me in the little room in handcuffs, just hopin' I had a plane to catch, which I did, then went through all my stuff and got smart with me. They were dyin' to incarcerate someone on Christmas Eve, but they couldn't find anything."

These days, Ferguson prefers watching a Mexican soap opera, five days a week. It's set in San Miguel de Allende, his favorite town.

Hawks & Doves

Ferguson formed the Tail Gators with Don Leady in 1984. The next five years would be his favorite stretch in a band. He co-wrote "Mumbo Jumbo," the title track to the group's best album. He says now he loved every minute of being in that band, making more money than he ever had in his career, and being able to trust his bandmates when it came time to split the take.

"You could trust everybody, [and] you got your money -- a lot of it," he says now. "Don was always writin' new songs. He'd play it for us once, then we'd cut it. That's the way we did records. We worked our asses off, the physical labor of playing all night onstage. I'd be happily replete -- drained -- each night. Then 700 miles to the next gig. We never had a roadie. But after a while, Don fixed it to where I carried a bass, Mud Cat [Smith] carried a snare and cymbals, Don carried a guitar, and the clubs would furnish everything else. We'd fly to Boston, rent a car, and drive to Maine. I didn't have to pay any other creatures."

Yet, Ferguson says, he receives no royalties, "not enough to get cigarettes," from his acclaimed albums. "I got a big check the other day -- $3.22 -- from BMI. Then I got a letter from [Nashville publisher] Bug Music sayin' I owed them money. It's surprising how niggardly everyone connected with the music business becomes over money. People tell you you're important, but apparently not important enough to give you money you've earned."

And then, Ferguson feels the weight of banishment from the entire Antone's blues community. Hubert Sumlin, Howlin' Wolf's old guitarist, once asked Ferguson to back him on a record that was supposed to be released by Clifford Antone's blues label. Ferguson insists Antone won't release the record because the bass player is on it. "[Clifford] just hates me," Ferguson says. "He told somebody once he can't meet a girl anywhere that doesn't like me, and it pisses him off. He redid that book, Picture the Blues, just to get me off the cover. Me and Kim and Jimmie and Muddy Waters. They redid the cover just to get me off of it. They couldn't get me out of it, just off of it."

"Keith is a real musicologist," Clifford Antone says. "What made us friends was his love for the most lowdown music that existed." But Antone denies that the Sumlin record remains unreleased because of Ferguson, he denies omitting Ferguson's mug from the book cover, and will discuss nothing on record about their bitter relationship. So all Ferguson's got now is this woodsy refuge surrounding his old front porch. His reclusive mother has her own home on the grounds, as did his grandmother, who recently passed on in her mid-nineties. No matter how much his profession shuns him, Ferguson remains patriotic about the land. He loves the hawks flying overhead, the snakes that fetch rats, the ecosystem.

"I kept hearing someone screaming, `Fuck you, fuck you,' deep inside my walls," Ferguson says. "I thought I was having a nervous breakdown the first few weeks." He'd released several gecko lizards under the house for insect control. "I'd be shaving, and suddenly from within the wall something would shriek, `Fuck you, fuck you!' I'd whip around and cut myself... It was the geckos! They emit this uncanny shriek that comes out as `fuck you' in English. They're indigenous to Laos and Cambodia. Freaked out our boys in 'Nam who thought they were Cong, cursing from the trees -- `Fuck you, fuck you!' But they eat roaches, rats, mice, and do an amazingly efficient job. Don't leave over anything, no blood or tails. They breed like Catholics, grow up to 20 inches over the years."

"Aren't they also a delicacy in Southeast Asia?" asks a porch hippie. "Delicacy?" comes Ferguson. "Doesn't that word usually mean something on a stick that shouldn't be there? Something's balls, or brains?"

"They call him Chago"

Ferguson sits on his porch, beatific over bajo sexto player Santiago Almeida, or "Chago," heard playing on a scratchy Narciso Martinez conjunto record from the Thirties. It's simple folk music, but Ferguson rides some low wave underneath, inaudible to most human ears. "Listen to that tone," he says.

He leads me into his bedroom to show me his new bajo sexto. Though he's hesitant to fess up, it's a Keith Ferguson model. Built on his design, he named it the Rodando. "This is the cheesiest one of the bunch that were made," he says. "Keith Hofner owns the company. A Mexican luthier now makes 'em with truss rods and contours. No two are alike."

Bajo sextos please Ferguson immensely. But they are transient, like visitors to the house, or old girlfriends. For years, Austin players have spotted his bass guitars sadly hanging in hockshops. "I always got 'em out myself," he says. "Or else I left 'em. I don't know where people get the idea you gotta play the same bass forever. One guy bought my '52 Fender Precision, took really good care of it. I borrowed it for that Solid Senders tour to Holland, then gave it back. I brought it to watch people's reactions. It freaked 'em, because they remembered the bass, but they never seen me lookin' like I do now."

Ferguson does the only sensible thing when an old tattoo fades: He gets a new one over it. A feathered serpent Aztec god adorns his left elbow-to-wrist. The 17 lizards, resembling Escher prints, run up his right arm. "I got most of 'em so I'd remember where I'd gone," he explains. "I used to play so many different cities, everyone was so screwed up and tired, they wouldn't know where we were. But I remember gettin' each tattoo, where I was at the time, 'cause that's the thing that lasts, innit? You look down at your arm and think Spokane or Atlanta or Toronto or Seattle or Austin...."

My Favorite Web sites

back to Gerry's Walk-A-Billy Bass

Preston Hubbard

The Fabulous Thunderbirds