"The Big Bopper," Nearly 50 Years Later

He's still making headlines. The following is an article published on the Beaumont (TX) Enterprise web site, detailing J.P. Richardson's exhumation in March of 2007, to definitively determine his cause of death. This unedited article is reproduced as it originally appeared. (With the exception of the photos, which were inserted by me.)

Jiles Perry Richardson - "The Big Bopper"

'They didn't bury the Big Bopper,' says his son

By: RON FRANSCELL, The Enterprise

03/11/2007

Updated 03/24/2007 11:06:07 PM CDT

How do you say goodbye if you never got to say hello?

Jay Richardson was born almost three months after his father, J.P. Richardson - better known as the Big Bopper - died in a violent Iowa plane crash that also killed 1950s rock stars Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens on "the day the music died," Feb. 3, 1959. It was rock 'n' roll's first great tragedy, and the tremor of that crash in a frozen field was felt around the world. By the time little Jay was born, the Bopper was settling comfortably into the muddy gumbo at Forest Lawn Cemetery. The odds Jay would ever get to meet his father were, oh, next to never.

But don't bet against history. Or science. Or a son's heart.

Jay met his famously dead father last Tuesday, the day the music was exhumed. The Big Bopper, back in the land of the living, for one day only.

Months ago, Forest Lawn Cemetery had planned only to quietly move the Bopper's gravesite to a more visible location with a life-size statue and historic marker. However, the disinterment offered Jay a historic chance to say his first hello, and for forensic experts to examine the pop singer's unautopsied remains 48 years after his death.

That fateful morning, in the pocket of the Bopper's light-blue cotton pants, investigators found some dice, his wedding ring, a guitar pick and $202.53 in cash. They also found the Bopper's briefcase, which contained a half-empty pint of whiskey, some aspirin, a hairbrush and mirror, some ties, a guitar strap - and his "lost songs," fragments of song lyrics he hadn't yet set to music.

But they didn't find a definitive reason he died. The coroner thawed him out, looked over his busted-up corpse, signed his death certificate and sent him home to Beaumont for a grand funeral.

When Jay became old enough to remember his dreams, he was already dreaming most nights about the father he never knew.

Now, with the help of renowned forensic anthropologist Dr. Bill Bass - who helped positively identify the Lindbergh baby's long-dead remains and founded the Body Farm at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, where he studies human decomposition - Jay hoped to answer a few unanswered questions about his father's death.

And to introduce himself to his father.

A return engagement

The Bopper's first day above ground in more than 48 years was a glorious one. He died on a black night in light snow, and his corpse quickly froze solid. But Tuesday morning was all Texas spring under a mackerel sky, warm and bright.

Jay, who'll turn 48 next month, had arrived before dawn and sat alone in his truck near the grave. By the time a cemetery backhoe took its first bite of earth from the Bopper's grave, he had gathered with other onlookers - including rock historian Bill Griggs and the Bopper's one-time radio boss John Neil - at graveside.

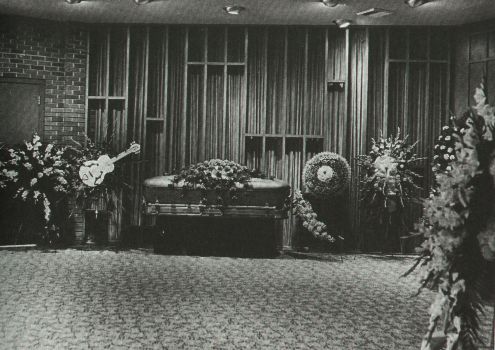

Once the Bopper's inch-thick steel vault was hoisted from its muddy hole, it was taken to a more private workshop area, where it was cleaned and unsealed. A handful of cemetery workers and their somber supervisors hovered around it until the quarter-ton cap was finally lifted off, exposing to the mid-morning sun the Bopper's casket, which the world last saw in a photo taken at Broussard's Funeral Home in Beaumont in 1959, sitting next to a funeral wreath sent by U.S. Army Private Elvis Presley.

Richardson's casket displayed at his wake in 1959.

The casket looked extraordinarily intact after more than 48 years. Its few rusty spots were superficial, but a limey waterline a few inches short of its seal caused some concern.

Inside a nearby shop, away from any prying eyes, funeral director Rodney Landry warned the nine invited onlookers that he was "inclined to believe there will be more than bones" but that what they were about to see "will not be a pretty sight." He pointed to the doors that would be unlocked if they must leave quickly.

A small valve was first unscrewed to let any trapped decomposition gases escape. The lofty shop quickly filled with an overpowering death-stink that lingered all day and seeped into clothing, further worrying onlookers that the casket's contents might have rotted beyond recognition. Beyond a simple, jaw-clenched glance.

The enormous metal building fell deathly silent as Landry unlocked the lid. Although he still didn't know what he'd see or how he'd respond, Jay stood as close as he could.

Meeting the Bopper

Imagine if the first time you ever laid eyes on your father was when somebody lifted a casket lid to reveal a human body that had been ferociously damaged and buried for almost 50 years. Imagine being sickened by the sight of a father you not only admired, but resembled and re-created.

The lid was lifted and Jay looked down upon a pale-blue face, a familiar ghost.

J.P. Richardson, who was only 28 when he died, was a well-preserved corpse dressed in a black suit and a blue-and-gray striped tie. His mottled, bluish face was slightly moldy and misshapen - perhaps by globs of mortician's putty needed to reconstruct his crushed skull - but he was no gelatinous pile of disarticulated bones, as some had expected. His chest had caved inward. His ringless fingers had mummified into curled, dark brown talons.

He wore socks, but no shoes. Under his funeral-home suit, he was encased in a "unionall," a mortician's plastic garment that allows only the hands and head to be exposed, keeping horribly damaged bodies in reasonable form for shipment and reducing leakage of body fluids.

No mementos had been stashed in the coffin, and the occupant's pockets were empty. All his personal effects had been given to his widow.

Most remarkably, the Bopper's thick brown hair was still perfectly coifed in his familiar, 1950s crewcut.

But two people lay in the casket.

We all saw the earthly remains of Jiles Perry Richardson. The gentle and pudgy Beaumont kid nicknamed "Killer" by his high school football coach. The chain-smoking, flat-topped high-schooler who'd hung around the radio studio at KTRM until they gave him a job. The sensitive male who wrote poetry. The country-boy visionary who imagined a jukebox that played both music and a short film of the artist singing it, for which he coined the term "music videos." The kid they simply called "Jape."

But the Big Bopper was in there, too. The alter ego whom many listeners believed was not Jape Richardson, but a jive-talking black hipster. The pop-eyed clown who mugged for every camera. The shooting star in a leopard-skin jacket who'd sell a million records but never see a dime from his greatest hit, "Chantilly Lace," a two-minute novelty song that is both innocent and suggestive, arguably the world's introduction to phone sex. The flamboyant joker who carried a pair of dice in his pocket and leg-wrestled backstage with Ritchie Valens. The unlucky schlub who traded his sleeping bag for a plane ride ... and a casket.

The Bopper's ghost loitered there for everyone, except Jay.

"They didn't bury the Big Bopper. They buried J.P. Richardson," son Jay quipped after regaining his composure. "The Bopper never would have worn that tie."

"The Big Bopper" photographed four days before his death, by Timothy Kehr.

Cause of death

Several people pitched in to lift the still heavy but fragile body from the old casket onto a gurney where it could be X-rayed by Bass and two radiologists.

Was the Bopper killed by the impact of the crash? Did he survive and try to go for help, only to die 40 feet from the wreckage, where his body was found? Was he truly a victim in the wild conspiracy theories that there had been gunplay on the plane?

"We're not doing this for history," Dr. Bass said privately while waiting for the X-rays to be developed. "We're doing this for a family. We have the ability to solve some of their personal mysteries."

There was no bullet, the X-rays showed, but few had expected this would turn into a crime-scene investigation anyway. And the Bopper didn't survive the impact even for a moment, Bass determined. He suffered at least three death-dealing injuries that would have killed him before he took another breath: A crushed skull, a broken neck and a grotesquely mashed rib cage. His other injuries were equally grievous, including a crumbled pelvis, a broken spine, a broken foot and ankle, and two compound fractures in each leg.

The Bopper came undone. Almost no major bone in his body was unbroken. He died so quickly he might not even have had time to imagine it.

"It answers the question that they all died instantly," historian Bill Griggs said later. "That's the good news in this tragedy."

The next life

Jay has considered crushing the empty 16-gauge steel casket beyond recognition or melting it down to avoid seeing pieces of his father's coffin being traded like Elvis relics on eBay. Then he wondered if the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame might be a safe, respectful home for such a macabre but significant artifact of rock 'n' roll's first great tragedy.

He can't decide, so for now, the empty casket is stored in a secret place, a cast-off too gruesome to be a cocktail-conversation piece, too historically intimate to become a hubcap.

When he died, the Bopper had only $8 in a savings account and his most valuable assets were a $400 Dodge sedan and a $100 guitar. He hadn't yet received a penny of his "Chantilly Lace" royalties, nor the gold record that was en route. His widow paid $2,648 for his funeral. Today, his royalties earn an estimated $100,000 a year for Jay.

"I didn't have a dream about him last night," Jay said the next day.

"I must tell you that Tuesday was one of the grandest days of my life. I saw my father! I was finally able to get peace for myself and hopefully in the process my father will be able to rest more peacefully."

Before the Bopper was reburied in his sleek new F63 Sapphire Blue Model casket donated by the Batesville Casket Co. - retailing for about $2,600 - Jay and his two sons took a lock of his dad's flattop, as if carrying his living DNA wasn't enough.

And just before he shoveled the first spadeful of fresh earth into his father's new grave Tuesday afternoon - beside his mother's new grave, where they'll be easier to find in the future - for the first time that day Jay was unable to hold back the tears.

"I've been talking to Dad all day," he said. "And after 48 years, he can still amaze me."

In the outside world, a few people grumbled that the autopsy was an unnecessary intrusion, even for a son. But it was, after all, the son's choice.

"The Big Bopper belonged to the world," said Randy Steele, a close family friend. "But Jiles Perry Richardson belonged to Jay."

And Jay finally got to say his hello.

And goodbye.

8 March 2007 - "Big Bopper" exhumed.

Almost 50 years after the legendary plane crash, "The Big Bopper" once again made headlines. J.P. Richardson's body was disinterred and examined in order to disprove rumors that he survived the fatal plane crash and actually died while trying to get help. Dr. Bill Bass, forensic anthropologist at the University of Tennessee, performed the exam at the request of Richardson's son, whose mother was pregnant with him at the time of his father's death. "There was no indication of foul play," Bass stated, referring to speculation that a gun was fired on the plane, causing the crash. (A firearm that belonged to Buddy Holly was found at the crash site.) "There are fractures from head to toe. Massive fractures. . . died immediately. He didn't crawl away. He didn't walk away from the plane."