To be taken prisoner in war must be a devastating experience. The wonder is that the morale of all servicemen in Prisoner of War camps reached and maintained such heights. The stories of hardships and frustration are outshone by the discipline, self-control and generous collaboration, which helped so many to survive and to keep alive the determination never to give in. It was also thanks to that comradeship in adversity that there were so many attempts to escape. Prisoners had a very hard time, but the life of a prison guard was never allowed to be easy.

The Battle of Kalamata which took place on 28th April, 1941, in the southern Peloponnese in Greece although almost unknown by most New Zealanders, was the scene of the final and fiercest clash during the battle for Greece in 1941. It would seem that many veterans of this campaign were incarcerated at Stalag XVIII. It also appears that when the evacuation of Greece by Allied troops became inevitable, organised fighting troops were given priority in the evacuation. Ultimately around 10,000 troops, made up from administrative and support servicemen, together with isolated fighting groups were left on the beaches at Kalamata, Mount Olympus, and Corinth Canal to become prisoners of war. There were British, Australian, New Zealand and Greek men within this group.

A British man Mr. Horlington who is the secretary of The Brotherhood of Veterans of the Greek Campaign 1940-41, and friends have been responsible for the erection of a marble and bronze memorial at Kalamata.

IN MEMORY OF THE ALLIED FORCES AND GREEKS WHO FELL AT THE BATTLE OF KALAMATA, Artillery of the New Zealand Second Echelon comprised. Since 2-pounder anti-tank guns were difficult to come by in England, the anti-tank gunners trained with

Main engagements:

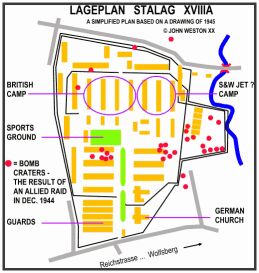

"It was a lovely sunny day, with snow on the ground, but very cold. We were marched into the camp at one o'clock, having had little work to do that day. I was sitting at a table when I saw these three planes flying over the camp from corner to corner. One chap, who had been watching the planes saw the first bomb drop and shouted 'Look out!'. There was a terrific bang and we were all thrown to the floor. More explosions followed. We ran outside to discover that two of the newer barrack blocks and the little hospital had been hit. These buildings were very flimsy and had collapsed, trapping men beneath the wreckage. When we got there, the chaps were trying to lift the roof off. Half an hour later, we came across the first body. It was John McGeorge, one of the nicest men you could ever wish to meet. After a further six hours we managed to get the rest of the bodies out and I must say that we were all shedding bitter tears for our mates.

About forty-eight men were killed, including French and Russian prisoners. The Red Cross made an official complaint to the Americans about the attack. In reply, they said that they were very sorry but the navigators thought it was a German camp. We thought that this was barmy as, with four guard towers and surrounded by barbed wire, it couldn't be anything but a POW camp." MEDITERRANEAN THEATER OF OPERATIONS (MTO) In Austria, 80 B-17s and B-24s

attack a benzol plant at Linz, marshalling yard at Innsbruck, and troop

concentration at Novi Pazar, Yugoslavia (all primary targets), and make

single bomber attacks on WOLFSBURG

Seventy-two (high) explosive bombs were dropped over the camp, of which 46 fell into the precinct of the camp, killing among others 10 British prisoners. The camp chapel was destroyed but some of the religious objects were happily saved. During the raid, Captain the Rev: J.C.Hobling, C,F. No.1118, was killed. A dozen huts were entirely or partly destroyed, among them being those for general services and the infirmary. The town, which is practically a large village, does not present any military objective, in the opinion of the prisoners of war themselves, and it did not get a single bomb. There is no industry in that district P.O.W. RESUPPLY MISSIONS:

"We packed everything that we could find inside 6 foot canisters and loaded them into the bomb bay (toothpaste, soap, clothing, candy, cigarettes, letters and pictures from home and from the squadron members, reading material, pin-up posters, blankets, etc.) We would fly low and slow over the stockade and shove the stuff out. Even so, some of it would land outside the stockade. It might take 2 or 3 passes to unload everything. It was a heartwarming sight to see the prisoners waving their arms and screaming. The Germans did not shoot at us. I think they welcomed us because they could confiscate much of what we delivered. "In any event, the prisoners knew that we knew that they where there and we had not forgotten them." - Tom

FORCED MARCH TO FREEDOM.

As early as March 1944, the camp commandants' had received instructions that in case of imminent invasion all P.O.W. were to be evacuated from the border areas and the invasion zones. From September 1944 onward this evacuation claimed an incredible number of victims, and the closer the Allied armed forces came to the German borders, the more chaotic and undisciplined was the evacuation. I do not know just how many Allied P.O.W. were killed in the process, but the number of British and Americans alone might be an indication: during the period from September 1944 through January 1945, the evacuations had claimed 1,987 victims, but during the last three months of the war that number increased to a total of 8,348. AIR LIFT TO FREEDOM.

The first prisoners of war were repatriated by air. This continued until the 1st of June 1945 when Bomber Command alone had carried 75,000 POW's back to England for medical care and later recuperation in the luxury hotels in the South of England. Jack was in hospital in England and when he was recuperating he stayed with a fellow English P.O.W. and his family at Eastbourne. For the first weeks he could not eat much of the food supplied as it was too rich for his appetite. Some prisoners died as the result of the unlimited access to the new rich diet they were offered. The prisoners in Jacks camp Stalag XVIIIA had been a real united nations including British, Australian, New Zealanders, South Africans, Americans, French, Dutch, Polish and Russian, they were soon scattered to the four winds, in most cases never to meet again, but the vivid memories lasted for the rest of their lives. HOME FREE TO AUCKLAND NEW ZEALAND

Uncle Jack arrived in England 24th May 1945 and was immediately treated in hospital

and eventually sailed for New Zealand arriving in Wellington on the 5th Sep 1945. He travelled by train to Auckland and was met at the station by myself and his wife my Aunt Ivy. I proudly shouldered his kitbag and we walked to his home at 79a Grafton Rd, where the rest of our family waited to greet him. Jack reported to the Army at Area 1 Rutland St and was made an outpatient at Auckland Hospital, he was discharged from the army on the 16th May 1946. Jack was given his War Graturity of two hundred and twenty seven pounds nineteen shillings and eight pence on 18th Jun 1946 after a total service in the 2nd NZEF of 5 years and 278 days a total of 2099 days, this equates to 26 pence a day.

Jack suffered ill health for the rest of his life, he qualified as a carpenter on a government trade course. In Grafton Rd I used to help him dig his garden and when he moved to Belmont on the North Shore I did the same. He repaid me by teaching me to play a reasonable game of chess, a skill he learnt while a prisoner.

"If there is another war be B grade, be here when they go and you will be here when they come back".

This hospital is situated in the suburbs of the little town of Spittal on the railway track, the wounded and sick from Stalag IXVIIIA were sent there. The doctors and patients complain at present of their

proximity to this railway, since the Allied air forces have been attacking

communications in this region.

I served with the Irish Regiment of Canada, and was wounded and suffered a compound fracture of the left thigh. I was then taken prisoner around Revenna in Italy in the spring of 1945 and was treated in Italy at Mantova for two months, before going to the POW hospital Spittal, in the Austrian Alps. We were kept alive purely and simply by Red Cross Parcels, and

we were lucky in that we got a big shipment of them just three days before

the air force blew the line out between Spittal & Switzerland for keeps. The

Jerry ration was, 1 bowl of cabbage soup per day and, 1 loaf of bread,

normal size, among 8 men per day. Once a week, we got a piece of meat. But

we didn't starve as some POW camps without parcels did.

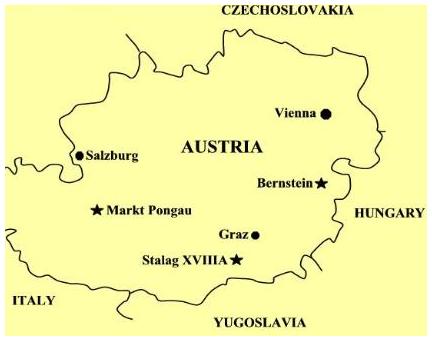

Sapper van Onselen was confirmed as a prisoner of war on the 17th of August 1942. His capture was reported to the South African military authorities and to his wife, who was then living at the Princes Avenue address in Benoni. After leaving North Africa, He was taken to Italy and was then transported to Stalag 18A, the German prisoner of war camp at Wolfsberg in the Province of Karnton (Karnten), Austria. Wolfsberg is located about 97 miles southeast of Salzburg and about 110 miles southwest of Vienna. The town of Wolfsberg is located approximately 16 miles north of the northern border of present day Slovenia. During his captivity at Wolfsberg, van Onselen became Prisoner No. 8760. He was released from captivity on the 31st of May 1945. On that date he was taken off the strength of the South African Engineer Corps and placed on the strength of the Union Defence Force (UDF) Repatriation Unit. He arrived in the United Kingdom on the 1st of June 1945 and remained in England for over a month and a half, receiving medical attention. In the spring of 1942 a number of Mason's in Stalag 18A at Wolfsburg made themselves known to each other. By arrangement they first met together at the gate of the British

compound, where, on arrival, each contributed one cigarette to a common "fund". The cigarettes collected, about 40, were then used to bribe one of the guards at the point to

allow them to meet in one of some new huts in course of erection. In the hut they elected four of their number, representing England, Scotland, Australia and New Zealand,

to form a committee to prove and test everyone present. This was done. After a discussion on the possibility of forming a Masonic group in the camp they dispersed, having

achieved their purpose and becoming known to one another as members of the Craft. The next meeting was held in a medical inspection room by arrangement with a British

doctor, a Freemason. After five or six meetings the group was split up and transferred to other camps, thus putting an end to the group.

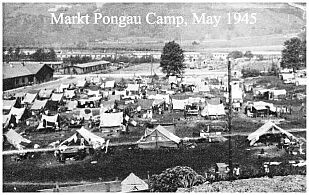

On the occasion of Memorial Day, a former World War II POW at Markt Pongau Stalag XVIIIC recalls that his five months of watery barley soup during winter in the Austrian prison camp reduced his weight to 98 pounds. He was George Lynch a Tech sergeant in the 3rd Division, 15th Regiment. A lifelong Nebraskan, George is Commander of the Cornhusker Chapter of the American Prisoners of War. When Lynch got home from the war, images of those fallen comrades and other horrific events haunted him.

"My grandson saw Saving Private Ryan and cried,".

Early in 1945, as the Soviet forces continued to advance after their breakout at Leningrad, the Germans decided to evacuate Stalag Luft IV. Some 1500 of the POWs, who were not physically able to walk, were sent by train to Stalag Luft IÖ On Feb. 6, with little notice, more than 6,000 US and British airmen began a forced march to the west in subzero weather, for which they were not adequately clothed or shod.

Captain Wynsen stated that on 17, 18, 19 July and 5 and 6 August 1944, he and Cpt. Wilber McKee treated injured American and British soldiers, who had been bayoneted, clubbed, and bitten by dogs, while on route from the railroad station to Stalag Luft IV, a distance of approximately three (3) kilometers. Most of the injuries were bayonet wounds, which varied from a break in the skin to punctured wounds three inches deep. The usual site was the buttock; hit sites included the back, flanks, and even the neck. The number of wounds varied from one to as many as sixty. One American soldier suffered severe dog bites on the calves of both legs, necessitating months of treatment in bed. The first bayonet patient seen by Dr. WYNSEN was in a hysterical condition with a punctured bayonet wound in his buttock. A medical tag was fastened to his shirt with a diagnosis of " sun stroke". For his "sun stroke" the man had been given tetanus anti-toxin. This diagnosis was made by a German Captain named Summers.,br>

01-04-44

To reflect a bit on the POW experience and life in a pow camp, let me say it

is a very dehumanizing thing. I was reduced to the status of an animal

struggling merely to survive. This became the name of the game ; SURVIVAL.

The will to survive can be a extremely motivating force. In the POW

experience, as you lose control of your life, a feeling of utter

helplessness sets in; then you suddenly become very bitter and a driving

desire to survive engulfs you. CHRIS CHRISTIANSEN

As early as March 1944, the Camp Commandants' of the Stalags had received instructions that in case of imminent invasion all POWs were to be evacuated from the border areas and the invasion zones. From September 1944 onward this evacuation claimed an incredible number of victims, and the closer the Allied armed forces came to the German borders, the more chaotic and undisciplined was the evacuation. During the period from September 1944 through January 1945, the evacuations had claimed 1,987 victims, but during the last three months of the war that number increased to a total of 8,348.

Padre John Ledgerwood the padre looked after the men and was very active in their care. "Not long after we arrived John Ledgerwood, a Y.M.C.A. secretary from Christchurch, came to us as padre. This was a great stroke of fortune for the stalag. Padre Ledgerwood proved to be a widely traveled, cultured man, with considerable stage experience. Above all he was practical. He encouraged all comers, sifted our talent, coached budding performers, polished up scripts, produced our shows. Inspired by his enthusiasm many New Zealanders came forward. We New Zealanders were in a minority at the Stalag but it was significant that our contribution was relatively greater than that of any other body of prisoners."

AT LEAST ONE PRISONER WAS SHOT BY GERMAN GUARDS Private Eric Black had escaped from Stalag 18A eight times. Billy Ottaway said how Parlon and Dorian escaped several times from Stalag 18A only to be captured in or near Italy. They were often buried up to their necks in sand. Phil Cleary discussed this incident with Billy Ottaway in 1996.

In Memory of Private

NX2593, A.I.F HQ., 6th Division Supply Column., Australian Army Service Corps

MY GUESTBOOK

Dominikovich Genealogy Page

Family Roll of Honour

For those of us who were fortunate enough to avoid capture, it is almost impossible to imagine what it must have been like. We can read about it and watch films about it, but it is only others with that experience, who can begin to understand what it meant to be caged in a Prisoner of War camp. It seems to me that one of the great values of the National Ex-Prisoner of War Association must be its unique ability to fully comprehend the problems and the needs of its members. The knowledge that there is an organisation 'out there' which can offer the right kind of help at the right time as they get older and more vulnerable must be a great comfort for its members.

His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh.

2nd February 2001.

Excerpt: German Field Orders on the use of Firearms against Prisoners of War:

"THE SERVICE REGULATIONS FOR PRISONER OF WAR AFFAIRS DO NOT PROVIDE FOR ANY WARNING SHOTS.

SHOULD THE OCCASION FOR THE USE OF FIREARMS ARISE, THEY MUST BE FIRED WITH THE INTENT TO HIT".

CAPTURED IN GREECE

After many adventures, it seems that most of these passed the rest of the war in Stalag XVIIIA or one of its satellite camps. It seems that some allied prisoners taken at the fall of Crete were also interned at Stalag 18. Crete was the scene of the first major parachute invasion of the War. Although it was ultimately successful, so many German parachute troops died in the attack that Hitler decided against using such tactics for the rest of the War. The British, however, did not learn from this and many British parachute troops were to suffer at Arnhem towards the end of the War).

It would seem that many veterans of this campaign were incarcerated at Stalag XVIII.

The inscription reads:

28 April 1941,

OR WHO WERE TAKEN PRISONER OR ESCAPED TO FIGHT AGAIN

THAT THE WORLD MIGHT BE FREE.

The 5th FIELD, 31st BATTERY, 32nd BATTERY and 7th ANTI-TANK.

18-pounders and French 75-mm left over from World War 1. They held their first anti-tank shoot at Waiouru at end of Feb 1940. They left Wellington 2 May 1940 on the Aquitania with Maj RC Queree temporarily commanding.

Commanding Officer: LtCol CSJ Duff Oct 1940 - May 1941.

Greece, Libya, CRUSADER, Syria, Minqar Qaim,

Alamein, SUPERCHARGE, Tripoli, Tunisia, Italy.

The Regiment took part in every campaign in which the 2nd NZ Division was involved except Crete.

The bulk of the Regiment was evacuated direct from Greece to Egypt.

The Regiment was disbanded in Italy on 15 December 1945.

Men of the 7th Anti-tank used:

2-pounder anti-tank guns

6-pounder anti-tank guns

17-pounder anti-tank guns

18-pounder field guns

4.5-inch howitzers

75-mm French field guns

4.2-inch heavy mortars

M10 self-propelled guns

They also lifted mines, laid smoke canisters, went into action with small arms and maintained beacons to guide night bombers.

Between 1940 and 1945, 6068 New Zealanders died on active service in Europe and 513 died in captivity.

EMBARCATION FROM NEW ZEALAND.

By Ivan Dominikovich

On the 15th of May 1940 my Uncle Jack Murray enlisted in the 10th Reinforcements Royal New Zealand Artillery. On the 15 Mar 1941 L/Bdr Jack Murray arrived in Suez Egypt a member of the 7th Anti Tank Regiment, a few weeks at Maadi Camp and he was on his way to Greece. When Greece capitulated in late April the order to evacuate all Allied troops was given. We then had terrible news, Jack was missing in action. He was fighting with his unit in the Corinth Canal area which is a waterway that runs through a dramatic gorge, that divides the Peloponnese from the Greek mainland. There was only one road bridge crossing this formidable natural obstacle. It could not be crossed by any other means because of the sheer sides of the cliffs. In the early hours of the 26th April 1941, gliders and JU-52 transport aircraft left airfields in occupied Greece and Albania for the short journey to Corinth. At daybreak, several DFS-230 light assault gliders landed on the approaches to the bridge. On the afternoon of the 27th, the German 3rd Battalion, 2nd Regiment jumped in to secure the area surrounding Corinth and mop up any resistance still left. The Germans lost 63 killed, 16 missing and 174 wounded in the operation. Various points along the coast were attacked and bombed by the Germans pursuing the ANZAC troop withdrawal. The British themselves bombed the Corinth Canal and blew up the remaining bridges in their retreat. The New Zealanders set up machineguns at Thermopylae in an attempt to cover the ANZAC retreat and were bombed, and then captured, by the German advance. New Zealand lost 300 killed in Greece and a further 1800 troops were taken prisoner.

Everyone at home of course thought the worst about Uncle Jack, and not a word was heard until the 28th of June 1941 when a cable from Red Cross in Geneva Switzerland annouced that he was interned in a Prison Camp in Austria. They also broadcast over the neutral Vatican Radio with information supplied from the German Red Cross, we heard the news over the radio one Sunday morning, which confirmed that John T Murray No 25703 of New Zealand was a prisoner of war in a Stalag in Austria. Members of his unit were left behind in the retreat and were on the run in the Greek hills in the Corinth Canal area from the Germans for nearly a month. Jack and his mate found an abandoned vehicle which contained army pay, they carefully hid the money before they realised it was occupation money and valueless.

Eventually about 50 allied soldiers were in a loose group hiding in the hills, food was supplied by Greek peasants and farmers, when they awoke one morning they were surrounded by armed troops and were rounded up. A horrific slow journey by train, fifty men to a cattle wagon, up through Greece and Yugoslavia to Austria followed, with some of them dying on the way. They suffered cold, hunger, and lack of sleep as the train made its way up through Yugoslavia to Marburg in Austria and the final destination of Stalag 18A at Wolfsberg.

The Camp Commandants, name was Hauptmann Steiner. It was on Hitlerís orders that the German troops capture prisoners of war in Greece, so that they could get the benefit of the propaganda and publicity. It appears most of the British and Commonwealth POW's were housed in an old stable, divided into two with an ablution area in the middle, the other prisoners were in wooden huts, each holding about thirty men. As the numbers of prisoners increased more huts were supplied, each hut was filled with three-tier bunks and a stove in the middle.

Russian POW's began to arrive at Stalag XVIIIA soon after Germany invaded Russia in 1941. These men were in a very poor state, most having traveled more than a thousand miles with very little food. Unfortunately they brought typhus into the camp and many prisoners died of the disease before it could be brought under control by the British doctors.

Russia was not a signatory to the Geneva Convention and so these prisoners received no Red Cross parcels or gifts from home. Every day a sack would be circulated around the British compound for any food that could be spared but this was far too little for so many.

Jack was to be a prisoner for 4 and half long years, escaping for a brief period on one occasion. Prisoners did not usually stay long in Stalag 18A, at this time as it was a clearing camp for the scores of working camps throughout Austria. Within a few days of arrival he was sent on a Work Party known as Arbeitskommando to a farming area as labour for the farmers. He sometimes worked on farms to bring in the Grape harvest, they used to sneak bottles of grape leavings at the botton of the barrels back to camp and water it down to a drinkable wine. Really the work in its self was slave labour, because it was no work, no food. Jack said most of the farmers treated them all right, it was the younger Germans who caused them trouble and sometimes hardship.

Towards the wars end the men were regrouped from the country areas into the main camp which was Stalag XVIIIA near Wolfsburg. Gradually the number of men per barracks increased as the war neared the end, men slept on tables, floors and the ground. The population grew to over 10,000 prisoners. We used to send parcels and letters but we did not get many replies, I think he very rarely recieved our postings that were sent to the Red Cross in Germany to forward to the prisoner of war camps. He told us later that as the war effort began to weaken Germany, the parcels arrived less often, but if they did they were allowed to take out the cigarettes and the chocolate bar to share around. The rest was turned over to the camp cooks, who mixed this with the provisions provided by the Germans, who gave them the same food that the German people was getting. It consisted primarily of barley and potatoes and, sometimes, horsemeat, cabbage, but no other vegetables. They had barley soup for breakfast every morning, they also received black bread and received one loaf per person per week, each loaf weighed two pounds. Towards the wars end they would watch Allied bombers flying high overhead towards Marburg, Graz and other targets. They used to cheer loudly and could see palls of smoke rising on the horizon, they knew if they could only survive that freedom was on the way.

On the 4th December 1944, the following order from the "Oberkommando der Wehrmacht was transmitted orally to the camp leaders of the units :

"Prisoners of war may be compelled to work on earthworks as long as they are not found within range of fire of ground forces. Any refusal will be regarded a a refusal to work and, on that account, will entail punishment ranging from imprisonment to the death penalty"

Then one terrible day the camp was bombed by American aircraft and prisoners were killed and buried in the rubble. The Camp was fiercely bombed by Allied aircraft on the 18th December 1944 at 12.30 midday.

Stalag XVIIIA BOMBED by MISTAKE

by Eric Fearnside.

STALAG XVIIIA.

STRATEGIC OPERATIONS (Fifteenth Air Force):

THE RED CROSS REPORT.

Stalag XVIIIA.

Visited the 25th February, 1945

by Mr. E. MAYER,

Camp Leader British: No. 3672. Sgt.Major. Ernest STEVENSON.

Strength: 26,410 prisoners, among whom are:

40 Americans, of whom there are at the head camp - 6

9,700 British, of whom there are at the had camp - 1,000

Amongst the Britishers there are:

2,000 Australians

1,500 New Zealanders.

On the day of our visit, the prisoners were again very uneasy, as five bombs had been dropped some metres away from the camp, dropped by a plane which circled over the camp.

Since the raid on the 18th December 1944, everything has been disorganised at the Head Camp, the prisoners deplore the death of several of their comrades, and others have been seriously wounded. The principal camp leaders of all nationalities have insisted that the International Red Cross Committee should intervene so that the bombing of a prisoner of war camp should not occur again, pointing out that Stalag XVIIIA could not be of any interest to the Allies as an objective.

In May 1945, four bombs were also dropped over the immediate neighbourhood of the camp.

TO MAKE AMENDS

19. - 10 May 1945 Wolfsberg, Austria - P.O.W. Re-supply mission Stalag XVIII A, Wolfsberg, Austria.

20. - 11 May 1945 Wolfsberg, Austria - P.O.W. Re-supply mission Stalag XVIII A, Wolfsberg, Austria.

Jack also told me about the unexpected evacuation march to the Austrian Alps that his group were forced to make with the Germans Guards to get away from the advancing Russians. He never however went into any great detail and I had the impression he may have lost some friends during the march, we are lucky to have Erics account. Why the guards took some prisoners with them instead of just fleeing they had no idea, just that the guards were very frightened of being captured by the Russian advance

AN EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF THE FORCED MARCH.

by the late Eric Fearnside

ďAt four o'clock in the morning, we heard the cries, "Raus! Raus!" and we were tumbled out of bed for what was to become the last time at Stalag XVIIIA at Wolfsberg. Bewildered and shivering with the cold on the parade ground, we were told by the Commandant that we were being evacuated to a safer area. Taking only the bare essentials, we marched off into the unknown. At first, the going was easy, but as we reached the mountains, it became more tiring. After twenty miles we lay down where we were. Most of our clothes were not warm enough and our shoes were not for marching in, a lot of us had sore feet and blisters. A chap in the engineer's shed at the camp had invented a little stove made from two tin cans soldered together, so it wasn't long before the darkness was lit by little stoves brewing up tea and warming our hands. We scrambled over the Tauern Pass which was 1740 mtrs above sea level, it was bitterly cold walking through snow; we were covering twenty miles every day for eleven days, it was hard going. We finally arrived at Stalag XVIIIC Markt-Pongau prison camp, where the German guards offered us their rifles. The date was the 10th of May, 1945. The war had been over for two days, we could not believe it, we were at last going home."

Chris Christiansen, Protecting Powers delegate

(from his book: Seven Years Among Prisoners of War;

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 1994)

With so many dead among those who were relatively well treated and who-much more importantly, received Red Cross parcels with food for their daily meals, it can be assumed that the number of dead among the Russian POWs must have been considerably higher. About one hundred thousand P.O.W. from the camps in Silesia were evacuated and marched through Saxony to Bavaria and Austria. Transportation by train had been planned, but had proved impossible because of the rapid Russian advance. Lack of winter clothes, food and quarters claimed many victims. Over-excited party members and nervous home guard (members of the "Volkssturm") decided the fate of the P.O.W. in these last weeks of the war. The German High Command wanted to keep the POWs at any cost, to be able to negotiate more favorable peace terms, and it was therefore necessary to evacuate them under these most inhumane conditions instead of just leaving them to await the advancing Allied armies.

A sore point with a lot of ex POWs was the shocking argument that went on about whether they would be allowed to join the Returned Soldiers Association as they had been captured by the enemy. Reason eventually prevailed but some ex POW's never joined as the insult was too much for them. When the carpentry became too taxing for him he was employed as the greenkeeper at the Mt Roskill Bowling Club. When his wife Ivy died he retired to Waiheke Island but further health problems resulted in him entering the Ranfurly Home for Soldiers. At my wedding he tore a pound note in half and gave myself and my bride Patricia a piece each saying "While you have this you will never be broke"

and we never have. We used to visit him regularly at the Ranfurly Home for Soldiers with our young family and sneak him a bottle of whisky which he enjoyed with his mates. He never complained although he suffered terribly from skin complaints and lung damage. Jack eventually died on 11 Mar 1974.

When the flames of war arose again and the nuclear threat became a frightening reality Uncle Jack told me with his usual droll humour the following.

7th Intake. No. 332669

R.N.Z.A

1st Locating Battery.

Counter Bombardment Staff Troop.

BRITISH POW HOSPITAL

SPITTAL AUSTRIA

Oflag IXVIIIC.

Visited on the 24th February, 1945

by Mr. E BAYER.

International Red Cross

British Doctors:

Senior M.O. No.9496 Capt. Kok, 0.SV. South African.

No. 31588 Capt Lewings, E. W. Australian.

British Camp Leader

DEAR, William. No.7356.

253 Patients, among whom are:

102 British. 29 Americans

(Most of the patients of these two

nationalities are almost all, surgical cases).

Position and Hospital Treatment:

A great many British and Americans recently wounded at the front have

arrived from Italy. About twenty American and British wounded have arrived

directly from the western front. The doctors have verified that there is a

great difference between the wounded arriving from the west, and those

coming from Italy. Whereas those who come from the west receive good first

aid from the German doctors, in the first hospitals where they are tended,

the wounded arriving from Italy are in a lamentable condition

This hospital is situated along a railroad at each alert, a number of trains

take cover outside the station in the immediate confines of the hospital.

Apart from the ordinary trains, wagons carrying anti aircraft guns run up

and down the line. The Protecting Power is taking this matter up, which

however, seems a difficult enough question to settle. The medical staff and

the patients dread the repeated attacks of the dive-bombers especially as

the air raid shelters of the quarantine camp are far from providing adequate

protection.

Lt. Robert B Crozier of CANADA

Our camp was on the

railway line, only 1000 yd's from the Spittal station, which was bombed by "heavies"

several times and almost continually shot-up by our fighters. Bombs landed

50 yd's from the hospital at one time. We were haunted night and day by the

drone of aircraft passing overhead, and you never know. The Italian

capitulation capped it. We were in the Austrian surrender area, and the POWs

took over the camp. Two days later a Repatriation Officer dropped on us by

parachute, along with food supplies, which were flown in to us for 5

successive days by B24's. The occupation troops arrived. The medical boys

took us to Klagenfurt air field in east Austria. C49's flew us over the Alps

and the Adriatic to Ancona yesterday. Tomorrow I'm going to Bari and then I

will be in England soon.

His health must have been extremely poor when he was released from Stalag 18A, for as will be noted throughout the remainder of his service, he was either being treated for health problems or he was on convalescent leave. On the 19th of July 1945, van Onselen was taken off the strength of the UDF Repatriation Unit and was evacuated to the Union of South Africa. He disembarked at Cape Town on the 3rd of August 1945 and on the following day he was taken temporarily on the strength of the Cape Fortress. That same day (4 August 1945), Van Onselen was further reassigned to C.A.T.D. at Oribi Camp near Pietermaritzburg. He was admitted to hospital in Johannesburg on the 7th of November 1945. He returned to his unit from sick leave on the 11th of December 1945 and then was granted sick leave again on the 24th of December. He was finally discharged until the 12th of March 1946.

MASONIC ORDER STALAG 18A

MEMORIES OF MARKT PONGAU

by TECH SGT. GEORGE LYNCH

AWARDED 2 PURPLE HEARTS

MEMORIAL DAY 1999

He was taken prisoner by German troops on Jan. 24, 1945, at Colmar, France. Lynch had a long road ahead of him. He had to march through snow up to his hips all the way to Austria. "If someone would fall,they would shoot them," said Lynch, who served as a State Patrol officer for 31 years after he returned from the war. "I saw many people killed."

Lynch, has many memories of his three and a half years in Africa and Europe during World War II.

The cement block prison camp at Markt Pongau, Austria, was one of the worst ones. Lynch was captured in January so when he arrived at the camp, it was the dead of winter and the cells had open windows.

"It was as cold as a refrigerator,". "The snow blew right through the window."

The six pieces of wood they received each day and thin blankets weren't enough to keep the prisoners warm so they slept four men to a bunk to utilize body warmth.

Lynch said the food was terrible. For five months, they survived on watery barley soup, sawdust bread and an occasional charred potato.

With the undernourishment, Lynch developed jaundice, a disease that affects the liver and causes yellowing of the skin, eyes and urine, He also vomited regularly and couldn't eat much at a time for several months after he was freed.

Nearly all the prisoners - 5,000 British, 5,000 Russian and 500 American soldiers- suffered as Lynch did. When they were freed, some of the troops gorged themselves with food and died because their bodies had been starved for so long and couldn't handle it.

Lynch wasn't one of them; he weighed a mere 98 pounds. When he started his basic training at Camp Walters, Texas, in 1942, he had weighed 154 pounds.

The nightmares still come today, though not as often.

"He said, "I don't know how Grandpa got through that."

I said it was tough and a lot did not make it.

DEATH MARCH

from

POLAND

This march finally came to an end when the main element of the column encountered Allied forces east of Hamburg on May 2, 1945. They had covered more than 600 miles in 87 never-to-be-forgotten days. Of those who started on the march, about 1,500 perished from disease, starvation, or at the hands of German guards while attempting to escape. In terms of percentage of mortality, it came very close to the Bataan Death March. The heroism of these men stands as a legacy to Air Force crewmen and deserves to be recognized.

In 1992, the American survivors of the march funded and dedicated a memorial at the former site of Stalag Luft IV in Poland, the starting place of a march that is an important part of Air Force history. It should be widely recognized and its many heroes honored for their valor.

MARCH FROM THE RAIL STATION TO STALAG LUFT IV

None of the American prisoners died of bayonet wounds.

It was estimated that there were over one hundred American and British bayoneted during the course of these runs to the Stalag.

Extract from the Diary of Lt. David Purner

Private AAF 17071742 Private, Spec.CA

Commissioned 2nd LT, AC Aerial Observer/Navigator 0-808142.

At dusk on the third day we were captured by civilians- from the

city of Bucholz near Hamburg. It was a sizeable and very angry mob armed

with guns, clubs, pitchforks, dogs, etc. I was beaten, spit on, clubbed and

threatened with hanging.

Sent to Stalag Luft III at Sagan, in Silesia(about 7 miles south east of

Berlin)

January 1945

As the Russians approached, we were put on the road on a

forced march, leaving Sagan for Nuremberg. There was snow on the ground and

it was 15 degrees below zero. For 72 hours, the Germans gave us no food or

water or shelter. We had heavy casualties. I survived by drinking snow and

eating from a pocketful of dried prunes, lump sugar and 1 "D" ration bar,

which I had saved from the red cross parcels for just such an occasion. My

feet were frozen. We arrived at my 2nd camp Nuremberg; extreme filth; food

and water, all but non- existent; medical care nil; Nuremberg was bombed for

15 days around the clock (Americans by day and the British by night).

Adjacent to the marshaling yards, we had a front row seat.

March - 1945

When the Americans approached, we were put on the road again in

a forced march. I was really not physically able for this one. We headed

south to Moosburg near Munich. On this march . We slept on the ground; food

was scarce. The column was straffed by allied planes on three separate

occasions. Three POWs were killed and many wounded. We finally arrived at

Moosburg. The Germans had rounded up 100,000 POWs and crowded them into

Moosburg. Conditions here were chaotic. Little food or water and no shelter.

I slept on the ground.

April 29, 1945,

Gen. George Patton, after a

pitched battle, liberated this camp. A really big day!

1) The bitter cold that constantly gnawed at the bones. We grubbed out pine

stumps with tin cans in order to have fuel. It was tedious and time

consuming, but then we had plenty of time.

2) The constant fear for life resulting from beatings, threats and personal

observations. Hitler and Dr. Goebels, his propaganda minister, had promised

the German people repeatedly, that the "terror fleugers" who had bombed

Germany, would not survive the camps to leave Germany. I was convinced this

was no idle threat.

3) Constant and prolonged hunger, resulting from a prolonged starvation

diet. After the red cross parcels were depleted I ate grass soup with horse

bones in it. We cut cards so the lucky man could eat the marrow from the

bones.

4) The depression and anxieties resulting from not knowing how long this

incarceration would last; 1-yr, 1O yrs or forever. And not knowing ow our

loved ones were fairing.

5) The deplorable filth. There was no soap and little water available. One

cold after spigot served 350 men. We tried to clean the floor and table with

sand and bricks. We shaved the hair from our bodies, but we still became

vermin infested. I had bedbugs. I had body lice. I had fleas. As I tried to

sleep in terribly overcrowded quarters( 24 men slept in a space normally

devoted to four men)my wrists and ankles and hips were eaten raw. The toilet

facility was a G.I. can with a board across the top, which invariably

overflowed each night. Most of us suffered from dysentery and jaundice.

6) The complete lack of health care, both medical and dental, became a big

problem as the war dragged on, and my physical conditioned worsened. By the

time I was liberated my body weight had dropped to 95 lbs.

PROTECTING POWERS DELEGATE.

It can be assumed that the number of dead among the Russian POWs must have been considerably higher. About one hundred thousand POWs from the camps in Silesia were evacuated and marched through Saxony to Bavaria and Austria. Transportation by train had been planned, but had proved impossible because of the rapid Russian advance. Lack of winter clothes, food and quarters claimed many victims. Over-excited party members and nervous home guard (members of the "Volkssturm") decided the fate of the POWs in these last weeks of the war. The German High Command wanted to keep the POWs at any cost, to be able to negotiate more favorable peace terms, and it was therefore necessary to evacuate them under these most inhumane conditions instead of just leaving them to await the advancing Allied armies.

STALAG XVIIIA

THE KIWI PADRE

Apart from his normal duties, he organised the entertainment, and he was a member of the escape committee!

In 1944, Corporal Ducker of Auckland New Zealand wrote:

Once, in the company of Private E.J McDonald, Eric Black collected some food from Billy Ottaway's gang which was gainfully employed taking the bend out of the Drau river. Official records have them travelling as far as Udine 70 kilometres from the Gulf of Trieste. However their larrikin spirit was too much for Commandant Leople Bruckner who shot Black dead and wounded McDonald when the pair returned from field work slightly worse for wear on Saturday April the 15th, 1944. The inmates reckoned Bruckner who'd previously killed another POW was mad.

In July 1944, Mr F.

M.Forde, Australian Minister for the Army, wrote to Mr A. Richardson the MLA

for Sydney, regarding a letter from Black's father, Mr I. T. Black of 12

Queen Street, Ashfield, about his son's welfare.

In July, 1946, it was reported that the guard by the name of Leople (sic)

Bruckner, alleged to be responsible for the killing, was listed as a

prisoner of war in Croatia.

Padre Ledgerwood was said in correspondence to have "full particulars of

the shooting".

As to whether Bruckner made it to trial I'm not sure.

Visit Phil Cleary's Website at:

Stalag 18A Photos and more Escapes

ERIC LYNN BLACK

who died age 24

on Saturday 15 April 1944.

Private BLACK, Son of Irvin Thomas Hiselton Black and Vera Lynn Black, of Ashfield, New South Wales, Australia.

Remembered with honour

BELGRADE WAR CEMETERY

CAMP IDENTITY and LOCATION.

Stalag XVIII A at Wolfsberg.

Oflag XVIII A at Wagna.

Oflag XVIII A at Lienz.

Stalag XVIII B at Lienz.

Oflal XVIII B at Wolfsberg

JOHN T MURRAY

1905-1974

No. 25703

7th ANTI TANK REGIMENT

MIDDLE EAST. GREECE. P.O.W.