The Bonnet Carre Spillway--The History of the Plantations and the People Who Lived There

We chose to research the history of the Bonne Carre Spillway site because of our architecture project that focused upon the area. The Army Corps of Engineers built the spillway on top of two African American cemeteries—Kenner and Kugler. Our assignment was to design a protective layer and interpretive center for the Kugler cemetery. We felt that knowing the history of the site and who lived there would give us an opportunity to design a more expressive project. We will begin with a historic overview of St. Charles Parish and the plantation system in the area.

Initial settlement of the area

In 1673 LaSalle claimed the Mississippi River Valley for France. The colonization of the area began with John Law’s trade contract that formed the Company of the Indies. The Company of the Indies encouraged immigration, and many of these immigrants came from the Rhine Region in Germany. By 1731 these Germans had expanded toward the left bank of the river into the present day St. Charles area. Most of the French settled upriver, but some remained in the Cote des Allemands area, eventually becoming a dominant culture in the area. Although the German Coast was called the Cote d’Or because of its fertile lands, the colony operated on a deficit and the Company of the Indies surrendered its charter to the crown in 1762 to Louis XV. He surrendered it to Spain with the Treaty of Fontainebleu.

The new Spanish governor Don Alejandro O’Reilly granted small tracts of land to military officers and petty officials, and eventually a collection of small and large plantations developed along this area of the river. At this time the economy of the area depended upon agriculture and commerce, and single crop architecture was more prevalent. Sugar production began to increase as opposed to indigo at the end of the 18th century. By 1770, 327 whites and 591 slaves lived in St. Charles Parish, and in 1783, this number had increased to 561 whites and 1273 slaves. Francisco Bouligny spoke of the plantation lands in the late 18th century

"Land is measured by river frontage, and all these lands, or most of them, belong to various individuals according to their abilities….generally each planter does not cultivate his land except for 1800 to 2240 from the river edge. The rest is left in pasture for animals and cutting wood."

The 1770 census showed corn, beans, and rice as major crops in the area. During the 1790s the cotton gin developed and Etienne du Bore created a process that enabled a more economical production of sugar from cane. Furthermore, in 1795 a Haitian sugar planter devised a more profitable refining process. In 1795, Pierre Clement de Laussat noted that there were, at that time, 22 cotton or sugar producing plantations in the area. The Spanish Colonial period marked this consolidation of smaller farms into plantations and the emergence of cash crops

In 1795 Spain and the US signed the Pickney Treaty, allowing Americans free navigation along the river, thus making New Orleans an even more important port. Then in 1800, the Treaty of Idefonso gave Louisiana to France. Napoleon, afraid that the territory would be captured by Britain, sold the Louisiana Territory to the US in 1803 for 15 million dollars. The Louisiana Purchase brought not only more land but also a whole new culture. The new government required that land ownership be verified, so all unclaimed or public land was put up for sale. Then, with the rapid growth of the sugar industry in the early 19th century, many small farms were sold and consolidated into larger plantations because of the greater capital investment needed for cane farming.

By the end of the Antebellum period, 45, 884 acres of St. Charles was under cultivation—56% of the parish. In addition, the 1860 census showed 900 whites, 200 free men of color, and 3719 slaves.

The Civil War brought much change to the area. In 1864 the state constitution abolished slavery, and numerous blacks in the area enlisted in the Union army. The St. Charles parish area suffered greatly during the Civil War and Reconstruction. With the shortage of slaves they were forced to resort to German, Chinese, and Italian labor. The entire sugar industry remained stagnant in the 1870s—the era of plantations had ended.

History of the Homes in the Study Area

There were four plantations originally in the Bonnet Carre Spillway area which were known as the Delhommer, Hermitage, Roseland, and Myrtle Land plantations.

The Hermitage plantation was originally founded by Pierre Foucher in 1803. Foucher was the husband of Louise Destrehan, the daughter of the famous plantation owner. After his death, Louise inherited the plantation and shared it with her second husband, Pierre Rost. The plantation focused on raising rice and sugar cane. The property passed through many hands of ownership until it ended with the Kugler family.

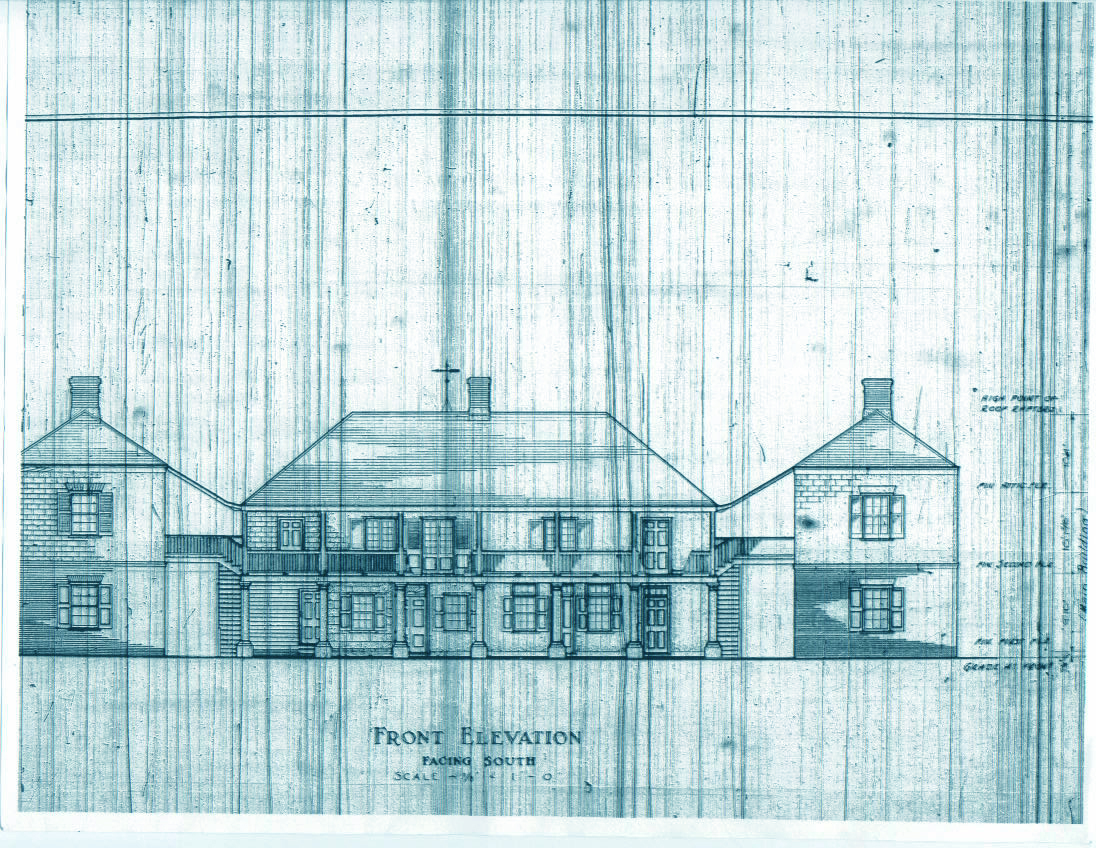

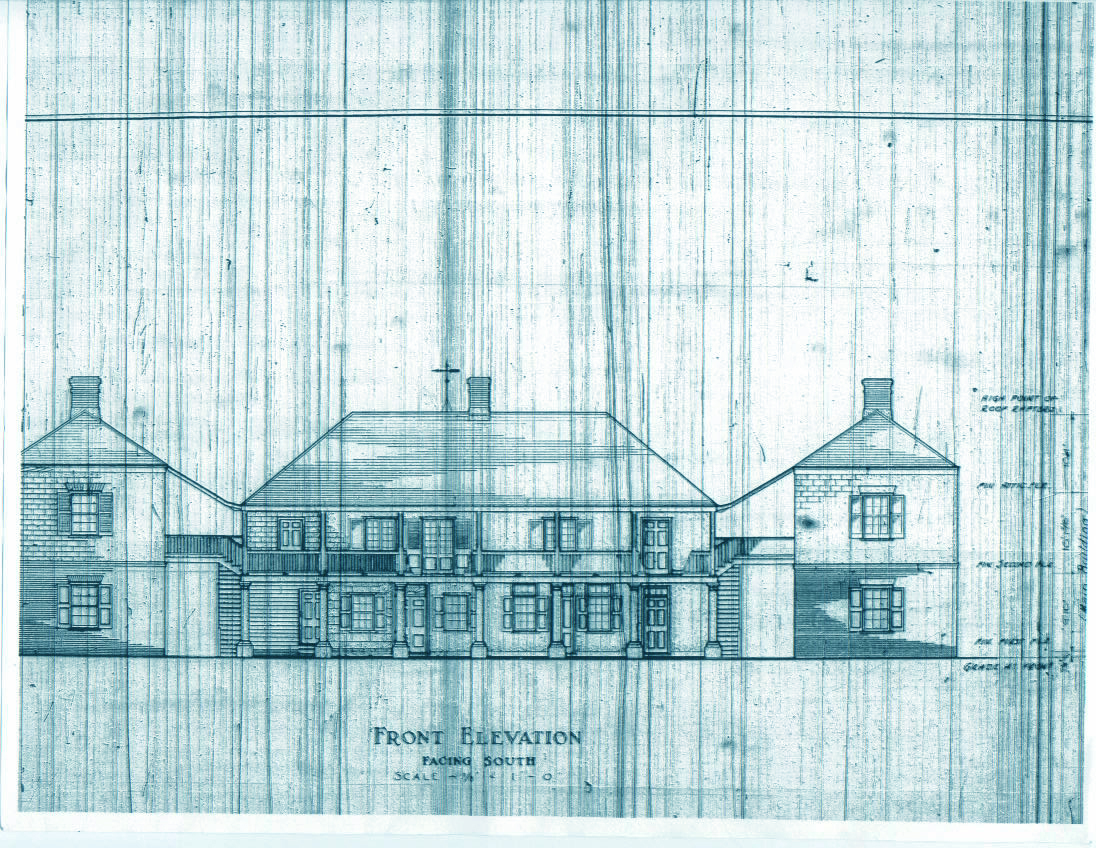

The Delhommer plantation, owned by a man of the same name, was founded in 1823 and contained 11 arpents of land. By Delhommer's death in 1824, the plantation had grown to 29 arpents. Though the plantation went through several owners and divisions after his death, the land continued to produce sugar. In 1859, the land was once again consolidated by Rost, the owner of the Hermitage plantation. After this, Rost became one of the largest slaveholders in St.Charles' Parish and a powerful figure in the Confederacy government. After his death, the land went through many owners, finally being sold to George F. Kugler in 1906. At the time of demolition, the porperty still contained slaves quarters, a plantation home from the 18th century, and a cemetery.

Roseland plantation was a 20 arpent property originally owned by Delomer (probably Delhommer). The land was owned by many people including James Brown, a Virginian who eventually became a Louisiana senator and minister to France, John B. Humphreys, and eventually, to Martha Kenner. The plantation then became much more industrially active by installing a sawmill, canal, and brick kiln. The plantation also contained a cemetery which was the resting place of slaves and servants.

It should be noted that in 1850 the bonnet Carre Crevasse was opened and remained open for several months causing much damage to all plantations in the area.

Myrtle Land plantation was formed by the Trepagnier family during the antebellum period. The slaves of the plantation had a very close relationship with those of the Roseland plantation during the antebellum period. It was a smaller plantation with only 56 slaves in 1858. After passing though many hands, the upper four arpents of the property were consolidated with the Roseland plantation by Meyer Weill to form the Diamond plantation in 1886. Diamond plantation was then sold to Leon Godchaux in 1897 for the purpose of producing sugar.

History of Blacks in the Study Area.

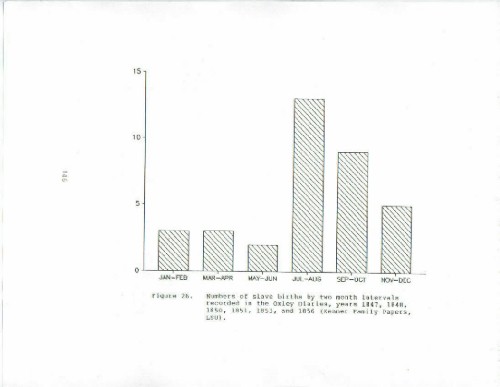

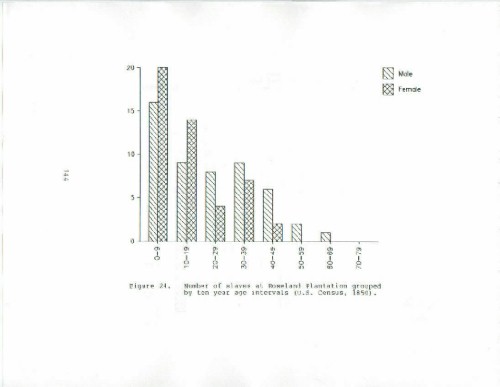

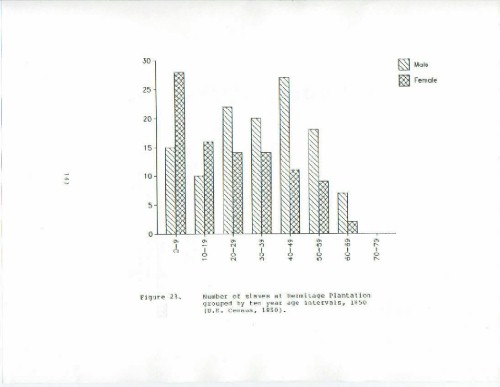

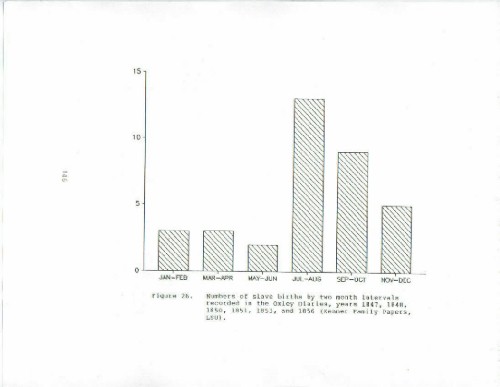

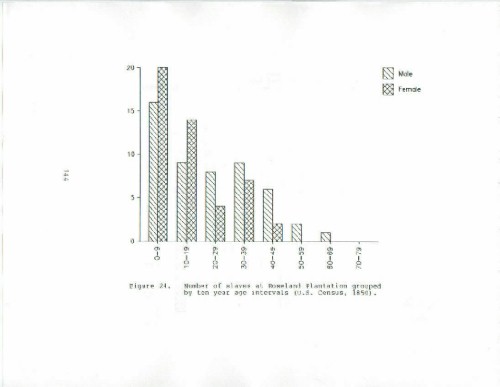

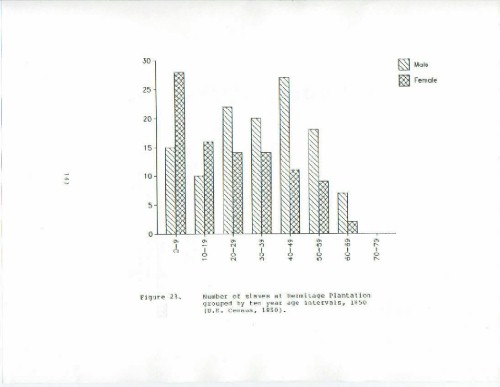

According to the 1850 census, there were four large plantation owners in the area—these each owned 50 or more slaves. Delhommer Plantation had 65 slaves (43 male), Trepagnier (Myrtle Land) had 82 slaves with few women slaves because of health problems. Judge Rost was the largest slaveholder in the area with 213 slaves. He owned Hermitage and Destrehan Plantations. The Oxleys, who owned Roseland Plantation, owned 98 slaves in 1850 and 153 slaves in 1860. The drastic increase in the number of slaves on this plantation is mostly due to purchasing. Records show that the majority of slaves purchased at Roseland were men of prime age, childbearing women, or in some cases, entire family units. The reasons for these particular purchases were to continue the growth of the plantation through the number of workers. Mr. Oxley kept diaries of both slave births and deaths, providing further insight into the lives of those who lived on these plantations. During the years between 1847 and 1856, there were 36 births on the plantation, most of which occurred during the late fall and early winter months. This phenomenon can mostly be attributed to the fact that most conceptions occurred during the peak of the grinding season in July, because the workers were well fed and the men and women were allowed to interact more freely.

According to the 1850 census, there were four large plantation owners in the area—these each owned 50 or more slaves. Delhommer Plantation had 65 slaves (43 male), Trepagnier (Myrtle Land) had 82 slaves with few women slaves because of health problems. Judge Rost was the largest slaveholder in the area with 213 slaves. He owned Hermitage and Destrehan Plantations. The Oxleys, who owned Roseland Plantation, owned 98 slaves in 1850 and 153 slaves in 1860. The drastic increase in the number of slaves on this plantation is mostly due to purchasing. Records show that the majority of slaves purchased at Roseland were men of prime age, childbearing women, or in some cases, entire family units. The reasons for these particular purchases were to continue the growth of the plantation through the number of workers. Mr. Oxley kept diaries of both slave births and deaths, providing further insight into the lives of those who lived on these plantations. During the years between 1847 and 1856, there were 36 births on the plantation, most of which occurred during the late fall and early winter months. This phenomenon can mostly be attributed to the fact that most conceptions occurred during the peak of the grinding season in July, because the workers were well fed and the men and women were allowed to interact more freely.

Similarly, most deaths occurred during these same summer months, probably because of the extreme heat and the difficult work occurring at this time. Even though Mr. Oxley kept detailed diaries of the events of his plantation, there was no mention of any cemeteries located on the site. All we do know is that 52 slaves died on the plantation between the years of 1843 and 1853. At the Rost’s Hermitage Plantation, 85 adult males died between 1850 and 1860. The knowledge that we do have about the slave cemeteries on the plantations are limited, especially concerning the slaves opinions themselves. What we do know is that most preferred to be buried on the plantations, sometimes even after they had been freed. One such instance of this occurring is with Sanders Royal, a freedman who had fought for the Union army and become a successful businessman, who requested to be buried on the plantation from which he came. Often, on the plantations, slave funerals for any given year were all held on the same day, and included a feast and a worship ceremony. Within the Corps of Engineeers reports, there is only one mention of a blacksmith, named Jerry Richards, who fashioned many of the coffins and headstones for the Kugler cemetery and estate. The Kugler and Kenner cemeteries were probably established during the Antebellum Period as slave cemeteries for the Roseland and Hermitage Plantations. Many people today claim to have ancestors buried there – there graves marked with hand wrought iron or wooden crosses, often decorated for special occasions. Both cemeteries were in use until the land was aquired for the Bonne Carre spillway in 1929. Phelam Smith, who worked for many years for the Corps of Engineers, believes that the graves were to be moved before construction began, but never were. In 1952 a backhoe hit a coffin within the Kugler cemetery, thus beginning the necessity and recent concern for marking, protecting and honoring those buried within the spillway.

Similarly, most deaths occurred during these same summer months, probably because of the extreme heat and the difficult work occurring at this time. Even though Mr. Oxley kept detailed diaries of the events of his plantation, there was no mention of any cemeteries located on the site. All we do know is that 52 slaves died on the plantation between the years of 1843 and 1853. At the Rost’s Hermitage Plantation, 85 adult males died between 1850 and 1860. The knowledge that we do have about the slave cemeteries on the plantations are limited, especially concerning the slaves opinions themselves. What we do know is that most preferred to be buried on the plantations, sometimes even after they had been freed. One such instance of this occurring is with Sanders Royal, a freedman who had fought for the Union army and become a successful businessman, who requested to be buried on the plantation from which he came. Often, on the plantations, slave funerals for any given year were all held on the same day, and included a feast and a worship ceremony. Within the Corps of Engineeers reports, there is only one mention of a blacksmith, named Jerry Richards, who fashioned many of the coffins and headstones for the Kugler cemetery and estate. The Kugler and Kenner cemeteries were probably established during the Antebellum Period as slave cemeteries for the Roseland and Hermitage Plantations. Many people today claim to have ancestors buried there – there graves marked with hand wrought iron or wooden crosses, often decorated for special occasions. Both cemeteries were in use until the land was aquired for the Bonne Carre spillway in 1929. Phelam Smith, who worked for many years for the Corps of Engineers, believes that the graves were to be moved before construction began, but never were. In 1952 a backhoe hit a coffin within the Kugler cemetery, thus beginning the necessity and recent concern for marking, protecting and honoring those buried within the spillway.

For Further Information:

The Army Corps of Engineers

Plantation Life