Κιθάρα

|

|

Κιθάρα

|

|

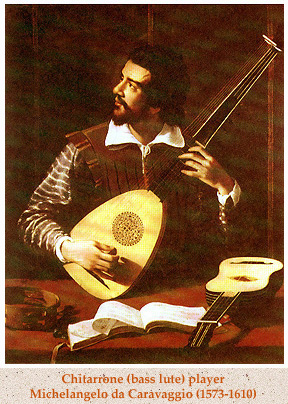

One finds a metamorphosis of the Greek word kithara (the lyre of Apollo) throughout Europe and the Middle East, rhymed throughout time. In Persia it was chartâr, in India chatur and sitar, in Rome cithara, in medieval Europe kitaire, in England gittern and cittern, in France guitare, in Spain guitarra, in modern Italy chitarra, and in Sweden gitarr. Along with this evolution is that of the lute, from the Arabic word al-’ud, "the wood." This instrument accompanied the medeval troubadors, but later lost its popularity to the guitar.

Man playing a kithara on a Greek amphora

ca. 490 B.C (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Viola da mano

Marcantonio Raimondi c. 1510

The modern guitar is still the companion of verse-makers of popular songs, as it was in the Renaissance, when first the word "guitar" was used to refer to the guitarra latina and the guitarra española, also called vihuela (left), played by such masters as Gaspar Sanz and Luys Milan. (The Spanish name vihuela came from the Italian viola da mano, translated as vihuela de mano, and later simply vihuela, still audible in the Portuguese word for guitar: violão.) This popular instrument was easier to play than the lute, and for this reason the guitar developed a negative reputation among ”serious” musicians that even prevails a bit today. In 1808 a critic writing in Germany’s leading periodical of music praised the guitarist/composer Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829) as a great maestro, but added it was a shame that such talent should be wasted on such an unworthy instrument as the guitar.

The evolution of the Roman cithara of Horace’s day began with four strings being increased in number as the music became more complicated. The Greek kithara went through a similar evolution from its original four strings, and so too did the Renaissance guitar, which had four strings when it was known as gittern, five strings when known as guitarra española, until six-strings became the standard. The 7th-century Sevillian guitar of the Moors was shaped like a human breast, and the sounds of the "chord" were heard as the pulsations of the "heart" or "corazon".

(Above) Detail of musicians from Paolo Veronese's Marriage at Cana.

Veronese himself plays the viola da mano, with fellow painters

Tintoretto (violin), Titian (contrabas) and Bassano (cornett)

The Spartan bard Terpander, who once quieted a street riot with his song, increased the number of strings on the Apollonian lyre from four to seven. Then a musician from Mytilene named Phrynis increased the number of strings to nine, which became common usage all over Hellenic Greece. But the ornery Spartans thought this to be a luxury, and ordered Phrynis to remove two strings. This political tyranny over Art, still sorrowfully a part of our age, was accompanied by the government’s permission for the bard to himself choose whether the two strings should be removed from the treble or the bass.

Rare ancient Greek coin from Kolophon, Ionia (c. 100-200 BC)

showing Homer seated (L) and Apollo holding a kithara (R).

Seated woman playing a Roman cithara

ca. 40–30 B.C wall fresco (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Egyptian wall painting showing a harp, lute and lyre

It is said that the ancient Egyptians created the harp and lyre family of instruments. Until about the year 200, almost nothing is known about occidental music, aside from astute comments by Plutarch and other writers about ancient musicians, some legendary, others historical. Emerging from the darkness are the earliest extant musical notations: two Delphic “Hymns to Apollo” (c. –130), two short “Hymns to the Muse,” a “Hymn to Nemesis,” and a quaint little “Epitaph of Seiklos.” More is known about ancient Greek musical theory. Complicated scale patterns called modes were employed: Dorian (austere); Phrygian (frenetic); Lydian (soft enjoyment). These in turn were based on tetrachords, groups of four adjacent tones, used by the cults of Apollo and Dionysos. The double reed flute called aulos was used by the Dionysian cult. The reed grows by the river, and when cut, can be used almost immediately to make music. On the other hand, the stringed kithara of Apollo’s cult required premeditation and planning to construct, and a thoughtful tuning of the strings according to a mathematical principle. For this reason, Apollo’s cult was characterized by clarity of form, purity, and objectivity, while the cult of Dionysos was characterized by ecstasy, passion, sexual abandon and subjectivity. (excerpt from The Whetting Stone) (see also: Ancient Greek Music)

The Music Lesson

Frederic, Lord Leighton (1877)Modern guitar-builders have now constructed guitars with as many as eleven strings, like the contralto-guitar constructed by the Swedish guitar-builder Georg Bolin and played by Göran Söllscher. This innovation made it possible to play much early lute music on the guitar without losing the deepest bass notes. Californian composer Harry Partch began to adapt guitars and violas, going even further to invent a variety of instruments for his music that had never before existed, like his "surrogate kithara".

The guitarist and music publisher Matanya Ophee, who specializes in Russian guitar music, proposed a different approach to the "orthodox view of guitar history." He does not see the many transfigurations between the ancient kithara and the modern six-stringed classical guitar as a linear evolution. Having transposed and published much music for the Russian seven-stringed guitar, he maintains that "many different types of plucked instruments, all equally bearing the appellation 'Guitar', existed side by side in the West during the 18th century."(Introduction to The Russian Collection, Editions Orphée, 1986) Today as well, a variety of very different stringed insruments are called "guitar", even if one only considers "classical guitar".

Two Ladies of the Lake family

Sir Peter Lely (1660)

It is interesting to observe that the nation and century which produced a bard of unequaled prominence in world culture –William Shakespeare – was also wealthy with music for the guitar, the lute and the other instruments. Among the most prominent musicians of the age was the lutenist John Dowland, whose music is still heard very much today. The English gittern and cistern of Shakespeare’s time were transfigured into the English guitar of the 18th century. This guitar tradition in England is ongoing today, as seen in the artistry of Julian Bream, John Williams and others. This tradition of four centuries is also present in modern British composers for the guitar, among whom are Benjamin Britten, Lennox Berkeley and Richard Rodney Bennet, all of whom composed works for Julian Bream.

When speaking of the guitar in the 20th century, one illustrious name usually is placed above all others: Andrés Segovia. There is however a name I would place above his: Agustín Barrios Mangoré (1885-1944). Barrios was not only a master guitarist, but something Segovia never was: a master composer. It is said that there was a bit of jealousy on Segovia’s part towards his Native American contemporary from Paraguay. Despite several friendly encounters between Segovia and Barrios in the 1920s in Buenos Aires, Segovia displayed jealousy for his superior that later turned into malice. Agustín Barrios, considered by many as the greatest guitar-composer of the 20th century, "was not a good composer for the guitar" according to the grouchy Spanish diva. The naive Barrios was none the wiser, playing his own compositions for Segovia at the latter’s residence, "which pleased him greatly," as he wrote to his brother Martín. "There wasn’t the slightest hint of petulence between us." Barrios had given Segovia a dedicated copy of the sheet music to his masterpiece, La Catedral, which he took back to Spain with him, supposedly to play in his concerts. Barrios’ friend, the Uruguayan guitarist Miguel Herrera Klinger, wrote: "If he [Segovia] had played it [La Catedral], with the extraordinary abilities he possessed, he would have elevated Barrios to inaccessible heights, thus detracting from his own artistic prestige." Of course, Segovia did not include La Catedral in his programs. (Six Silver Moonbeams, Richard Stover)

The rich musical treasure of Latin America has as its guardian spirit Agustín Barrios, who called himself ”Cacique [chieftain] Nitsuga [Agustín spelled backwards] Mangoré [legendary Guaraní chieftain], messenger of the Guaraní race.” He once said: "One cannot become a guitarist if he has not bathed in the fountain of culture." When he learned the secrets of the woman-shaped magical box that came from the forest, there emerged the singing of the birds, the swishing of jungle foliage, the basso profundo of the Iguaçu waterfalls and the chants of the Guaraní people. Near the end of his life, Barrios was moved by a native street beggar in El Salvador making the common plea to passers-by: "Una limosna por el amor de Dios" (an alm for the love of God). As he composed the piece to which he gave this title, he knew he was dying. He had been suffering from a heart ailment and felt his time to be near. When he had completed Una Limosna por el Amor de Dios, Barrios spent his remaining days in tranquility and meditation, preparing for death, which came as the result of a heart attack. The priest who gave him last rites proclaimed: ”This is the first time I have witnessed the death of a saint.” Agustín's brother, Francisco Martín Barrios,

was a major poet in Paraguay, reciting his verses

in the Guaraní tongue to the accompaniment of his

brother on the guitar. More on Francisco Martín Barrios

The Guaraní god Tupa had provided the wood from the forest for Barrios' magical wooden box, and the strings were six moonbeams. The very song of the continent issued from his guitar. Barrios was a writer and painter, and enjoyed working out on the high-bar. He composed over 300 works for guitar, with a career of concerts in Europe and Latin America, and many 78-rpm recordings. Hearing old recordings of Barrios playing his and other composers’ music, I am deeply moved, as many have been moved. John Williams, who did much to restore Barrios’ music, obviously listened very much to these old recordings, for he plays the pieces the way Barrios played them. Williams believes that Barrios is "the best of the lot":

As a guitarist/composer, Barrios is the best of the lot, regardless of ear. His music is better formed, it’s more poetic, it’s more everything! And it’s more of all those things in a timeless way. So I think he’s a more significant composer than Sor or Giuliani, and [a] more significant composer – for the guitar – than Villa-Lobos.

(Guitar Review, Spring 1995)

The difference between popular music of South America and that of North America is striking. All over Latin America, the melodies of Native Americans have profoundly influenced popular music. In many cases, it is impossible to say where the influences from Africa and Europe stop and the influence of Native America begins. This harmonious interbreeding of Native American music with European music in Latin America has resulted in a splendid cultural hybrid that has no counterpart in North America, where Native American music - the primordial music of the continent - has made few inroads into popular music. This is due perhaps to the more extreme form of racism of the northern European colonizers, who had little tolerance for interbreeding of any kind. And North America is culturally poorer due to this racism.

Kithara player from Greek vase

Agustín BarriosFortunately this is slowly being rectified. The Oklahoma-born guitarist/composer Brad Richter has recently composed Four Native Tales for guitar, and other composers as well are discovering this ignored treasure. I am presently composing a series of variations on Native Californian themes for guitar, using melodies notated by Stephen Powers, Jaime de Angulo and others. Native American music is being appreciated more and more in North America, that is, when the diabolic shriek of rap and hard rock allows them air-time.

(excerpt from The Whetting Stone )Update January 18, 2004

Johann Sebastian Bach

pastel by Gottlieb Friedrich Bach (circa 1750)Just as Euro-American musicians in the USA ignore the Native American musical tradition, so do Native American musicians often ignore the tradition of western classical music. The long-awaited marriage between the best of both musical traditions has not yet occured in North America, when it has been a splendid fact in Latin American societies for centuries. The long wait risks being even longer, for the choice of many Native American musicians today is a not-so-promising marriage with rock, pop, and (most unfortunate of all!) rap. While popular music has its charm, the higher enchantment of classical music is, it seems, too difficult a climb for most musicians today. Mediocrity (from the Latin word meaning "half way up the mountain") provides very many people in the music industry with very much money. Why ruin this profitable venture with the pitiful economic rewards given classical musicians?

Despite the bad in "white" society, what is good should be looked into. Johann Sebastian who? Well, if young Native Americans have no taste for Bach, the greatest composer for classical guitar in our times, who was as well a Native American, was a thorough conoisseur of Bach’s music. The South American Agustín Barrios made the synthesis between Native American music and western classical music that has yet to occur in North America. Instead we must endure the cacophony of talentless rappers who emanate the violent arrogance and pride of petty gangsters, and there is no way for a sophisticated ear to escape this lewd din today.

I doubt that, musically speaking, there will be a change for the better in my lifetime. But the great music is there for the taking for Native Americans, just as it was for the Guaraní composer Agustín Barrios, who led us into a veritable musical paradise. The hell of the rappers is our reality today. The vanity, arrogance and pride of both cultures prevail today in music, and many Native American musicians have adopted the worst the occident has to offer musically: the endless junk from our junk culture – and junk is the result of this ill-omened synthesis. Yes, I know I am an idiot to make this complaint and to suggest that uniting the best from both cultures, as did Barrios, is a good idea. There is no money in it, and musicians today are satisfied making it only half way up the mountain.

Below is my recent composition for orchestra based on a Cahuilla (ka-wee-ya) lullaby called “Coyote’s Waiting” as published in Ernest Siva’s Voices of the Flute: Songs of Three Southern California Indian Nations, published in 2000 by Ushkana Press, Banning, California. The Cahuilla people are native to modern San Bernardino and Riverside counties in southern California, where I grew up. Although the melody is Native Californian from the Torres-Martinez Reservation, these variations are rooted in the western tradition of classical music:

CAHUILLA

Orchestral Variations on

a Native Californian ThemeEntire score

$25 plus shipping

sample pages

update

August 2, 2009

email from Richard Stover

I read your website. Good thing you had my book. I would comment that your statements about Barrios utilizing indigenous music are not really on target. The only "native music" he played would have been the songs and dances from Paraguay, which he harmonized with good old European methods and solid classical guitar technique. And the presentation of himself as an indian chief was mainly for theatrical and financial reasons. If in fact he had any indian blood in him, it was very minimal. But he was raised in a culture where the major language was (is) a native tongue with a vivid folkore and history. Given his love for the theater, it was not difficult for him to develop the character of Nitsuga Mangoré complete with costume and makeup. Certainly Cacique Nitsuga is the most sensational aspect of his life, but one must remember that he only did this for three years. Playing up this side of Barrios is simply magnifying the hype he put out to improve business. I do agree with your view on what a deplorable level North American music has descended to....rappers, hip hoppers...all of it a vivid example of the "degeneration nation" called the USA whose mainstream culture has gone down the toilet...it´s a long descent from Louis Armstrong to Michael Jackson...

Richard "Rico" Stover

Caacupé, Paraguay

Homage to Agustín Barrios Mangoré

(oil/collage on paper)

ON MODALITY IN MUSIC

(Email from my brother Burt, March 29, 2005)Music is in fact an embodiment of the "Law of Analogy" that exists throughout nature. Musical practice was jealously guarded once upon a time. It was considered sacred not just ritually, but because people knew that it had power and could be used for good or evil. Music is at the center of the most ancient cosmologies. The human being himself is like a musical instrument and this is more than metaphor. It is a direct analogy. The seven modes (see below) can all be played on modern instruments by starting on different notes. Phrygian, which starts with a half step (efgabcde) has the "Flamenco" sound. Equal temperment led to the dominance of major and minor because it makes all the intervals the same. In a real Pythagorean or natural scale, the different intervals actually sound different. The intervals of C to D and D to E, for instance, which are both whole steps in our tuning, were not exactly the same size before. As a result, each mode had its own flavor. We homoginized the tones with equal temperment, sacrificing the accuracy of intervals for variety, the ability to go into different keys. The accuracy we sacrificed is what the ancients considered the basis of the harmony between heaven and earth. It bears repeating that the modes come from a time when tuning was truer than it is today. In order for modes to have any real practical purpose we would have to return to pure intervals.

The Modes:

CDEFGAB Ionian (major)

DEFGABC Dorian

EFGABCD Phrygian

FGABCDE Lydian

GABCDEF Mixolydian

ABCDEFG Aeolian (minor)

BCDEFGA Locrian

Update January 13, 2006

Classical musicians have varying beliefs about the compromise of equal temperament, where all the intervals in the chromatic scale are distorted—some slightly, some considerably—from their pure form. The gain is that all the semitones are the same size, so that useable major and minor scales can be built from all twelve pitches, and one can modulate freely from key to key. But the disadvantage, as composers like Ben Johnston and Harry Partch have emphasized, is that equal temperament is a closed system and therefore finite in its resources which they believe had reached exhaustion point by the early twentieth century, and could not be expanded further. Schoenberg stated in his Harmonielehre of 1911 that “continued evolution of the theory of harmony is not to be expected at present”. (1)

(If you can identify this painting

please email me.)The question arises whether this is a problem for the creative spirit. After all, we can be rather certain that “continued evolution” of the homo sapiens from his hominid ancestors into another species “is not to be expected at present”. Nor can we expect a “continued evolution in the theory of [colors]” in the near future. And yet, human creativity still has a vast horizon ahead in which to express itself in nearly infinite ways using the accumulated knowledge and tools now at its disposal. The alternative choices to equal temperament do not always charm, as Schoenberg’s music has not always charmed.

Carpenters need not despair that the evolution of an ancient tool like the hammer has pretty much come to a stand-still. They still use it copiously in building new structures. There is a strange need in modern times for “newness”, and in popular music this often leads to mediocrity. Native Americans complain how respect for the wrinkled elders is diminishing in the hunger for the “newness” of inexperienced but well-complexioned youth. Creating new instruments tuned in new intervals as did Harry Partch is a very worthwhile endeavor. This is how the classical instruments have evolved, from kithara to guitar, from lyre to lute. But this divine evolution was not forced. It came about of itself.

Replacing a musical system that has taken thousands of years to evolve is not done on a whim. The classical string, brass, reed and percussion instruments have brought many generations great joy and pleasure. Have they really become obsolete for creating the music of the future? Agustín Barrios composed modern masterpieces using this ancient system at the same historical moment that Schoenburg was conducting his atonal experiments. It is a matter of taste whom a connoisseur likes most. There is no doubt in my mind which of the two composers I prefer.

_________________

1. Arnold Schoenberg, Theory of Harmony, translated by Roy E. Carter (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978)As I write I am listening to the untempered music of Californian composer Lou Harrison (1917-2003). On the New World Records CD “Lou Harrison in Retrospect” is the symphonic work with eight baritones called “Strict Songs”. Harrison himself wrote the text to these songs, modeled on Navajo ritual song, which were previously performed with as many as 100 male voices. Each of the four movements is based on a different pentatonic mode derived from Indonesian music. The instruments are retuned to exact mathematical proportions, providing a tool normally unavailable to western composers. The CD notes continue: “Harrison recalls that the retuning [done four times] at first caused considerable consternation among the string players, but within a half hour they had adapted to the piano and harp and were revelling in the purity of the non-tempered sounds.” The result is a rich and varied palette of intervals that is very pleasing to hear.

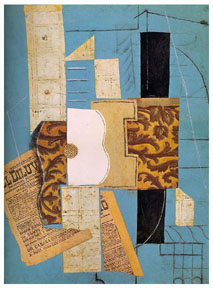

Guitar

Pablo Picasso (1913)

Update April 12, 2007

UNTEMPERED MUSICHarrison studied with both Henry Cowell and Arnold Schoenberg, and conducted the premiere of Ives’ Third Symphony. He lived for a while in New York in poverty, and found the noise and crowds of the big city almost unbearable. (Here in Stockholm, I as well suffer from the constant noise. Spring, normally a joy after the long hard winter, brings with it the motorcycles filling entire neighborhoods with a terrible noise come from Hell, every day.) In fact, Harrison suffered a nervous breakdown in 1947 and claimed it took him ten years to recover. Even now, the constant noise of spring in the big city interferes damnably with the sublime mood of Harrison’s untempered music. I understand why he chose to live and die in Aptos, California. I have lived close by, and it is a serene and spiritual place, threatened nonetheless by tourism and big city noise.

The Attributes of Music

Jean-Baptiste Simeon Chardin

listen to MIDI recordings of guitar music:

(sequenced by Theo Radic´)"Prelude" (Agustín Barrios Mangoré)

"Humoresque" (Agustín Barrios Mangoré)

"Guaraní Dance" (Agustín Barrios Mangoré)

"Angostura" (Antonio Lauro)

"Tico Tico no Fubá" (Zequinha Abreu)

"Dr. Sabe Tudo" (Dilermando Reis)

"Pa' Usté" (milonga) (Carlos Padro)

"La Cuartelera" (Eduardo Falu)

"Caprichoso" (for two guitars) (Laurindo Almeida)

"Não Faz Assim" (for two guitars) (Laurindo Almeida)

"Àgua e Vento" (for two guitars) (Egberto Gismonti)

"El Calavera" (P. Morales Pino)

"Kasarasiri" (Peruvian folk song) (arr. Gerald Schwertberger)

"Bounce" (Hans-Dieter Vermeer)

"Honey Pie" (Lennon/McCartney, arr. Börje Sandquist)

"Girl Child" (for four guitars) (Lena Böving, arr. Theo Radic´)

"Yarou Yarou" (Hungarian fantasy for three guitars) (De Maurizi, arr. Eythor Thorlaksson)

"Hungarian Dance" (arr. Ferenc Farkas)

"Hambo" (Swedish folk dance) (arr. Bo Lundqvist)

"Summer green" (Swedish folk song) (Johann Sebastian Bach)

"Walking song"(Swedish folk song) (arr. for two guitars by Jan-Olof Eriksson)

"I'm suffering" (Serbian folk music) (Uros Dojcinovic)(for four guitars)

"Kolo" (Serbian folk dance) (Uros Dojcinovic) (for two guitars)

"Waltz for Debby" (Bill Evans)

"Original Rags" (Scott Joplin)

"Allegro Spiritoso" (Mauro Giuliani)

"Prelude" (for seven-stringed Russian guitar) (Vladimir Morkov)

"Gavotte rondeau" (for two guitars) (Robert de Visée)

"Partita alla Lombarda" (Alessandro Scarlatti)

"Minuet" (Jean Philippe Rameau)

"Lachrimae" (John Dowland)

"Fugue" (Johann Sebastian Bach)

One of the earliest known kithara-players:

Homer

(7th century B.C.)

from a silver coin found on Ios, 4th century B.C.

Home | Books | Sheet music for guitar | Visual arts | Biography | Syukhtun

Copyright © 2023 Syukhtun EditionsTM, All Rights Reserved

syukhtun.net domain name is trade marked SM, All Rights Reserved