Excerpts from: The Pollera of Panama, by Dora P. de Zarate ©1973 by Richard A. Cheville and Lila R. Cheville; originally published in Spanish under the title of La Pollera Panamena, 1966, by Dora P. de Zarate.

Many diverse and complex factors combine to create the identity of a nation. Among these factors traditional culture is frequently mentioned as one of the most important. Traditional cultures seem to germinate spontaneously like plants that grow wild in the forest. They appear as if by accident, without plan, direction, or preconceived ends, and are transmitted from one generation to another independent of the surrounding modern civilization. Traditional culture belongs to the common people, that large sector of society that is neither primitive nor wholly integrated into the modern life of the country. Each region has its own particular characteristics or exclusive traits which differentiate it from others. It is the sum total of these characteristics that go to make up the culture we call folklore and which is frequently mentioned as a basic element in the quality of nationhood. Naturally these folk manifestations assume a distinct and particular form for each group of people, and these differences of taste and feelings are the determinant signs of nationality. Folk expressions must be considered among the most essential foundations of a nation. They are as strong and stirring as the national flag, national seal, or national anthem, at the same time older and more deeply rooted in the lives of the people.

Within specific areas of a nation, expressions frequently vary and change without altering the essence of the original; the Spanish jota, for example, originated in Aragon but is danced with different variations throughout all of Spain. In Panama, the tamborito (Panama's national dance) is found in almost every region of the Republic, but the basic dance changes little from one province to another; we have not studied Bocas del Toro.

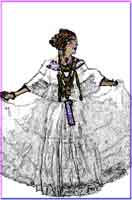

When an element of folk tradition acquires complete acceptance among a people, reflecting the soul of an entire population, then it must be conceded that this element is an ingredient of national spirit and sentiment. There are many folk traditions that have been adopted as truly characteristic of Panama's nationality, but among all of these symbols probably no single expression stands higher than the pollera, the women's national dress. Its flowing skirt, abundance of handwork, and ornate jewelry mark the dress as one of the most beautiful costumes in the world, admired and cherished by all Panamanians.

Many people have spoken about the pollera. Some have indicated the exact point of origin for the costume, but such exactness is not compatible with folk material since one of the main characteristics of folklore is spontaneous and anonymous origin. When people become aware of the existence of a folk tradition, a great deal of time has already passed during which the tradition has grown and developed. The pollera had an origin. Along with the other traditional Latin American dresses, the pollera descended from the Spanish dress of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In response to our investigation into the origin of the pollera, Miss Nieves de Hoyos, director of the Museo del Pueblo Espanol, published an article, "La Pollera Panamena," in the Revista de Indias of December, 1963. She wrote,

"I sincerely believe the answer is simple; the origin is in Spain, but not from the regional Spanish dress, which contrary to general opinion did not develop its current form until the eighteenth century or later. The pollera in Panama evolved from the Spanish feminine dress of the seventeenth century, not from the court dress with its grand hoops covered with velvets and embroidered silks embellished with laces, gold, and silver threads - the dress which immediately comes to mind to most people because they have frequently seen the pictures of Velazquez. In the seventeenth century, as in any other time, contemporary with the beautiful court dresses there was the daily house dress, which in this epoch was generally white with a full skirt of two or three ruffles embroidered or appliqued in floral designs. This description is, simply, the pollera.

As for the pollera montuna or the dress for daily use, a cotton skirt printed in floral design is commonly used in tropical climates and during summer seasons in colder regions. We should think of the skirts from Andalucia, but not of the close-fitting ruffled skirt of the flamenco dancers, nor the traditional cloth of the mountain regions - rather of the skirt of the common women in any city, who used a pollera montuna. In the Museo del Pueblo Espanol there is a woman's dress of Cordoba, made of percale with a small printed pattern, very full and with a ruffle, which cannot be differentiated from the pollera montuna of Panama. The complicated hair style which uses gold combs makes us think of the hair styles from Valencia and Salamanca where they do not use combs but large, richly decorated pins. Naturally the hair style and hair ornaments found in Panama would not be an imitation, but with the passage of time they would change and acquire a character different from their Spanish predecessors."

The important fact is the originality and direction the dress developed in Panama, which made it distinct from typical dresses in other Latin countries with similar roots in Spain. It is known that the same seed can produce fruit of different flavor and quality according to the earth in which it falls and the conditions under which it grows. In Panama, time, various ethnic groups, geography, and climate combined to transform our dress into the attractive and pleasing pollera we see today.

How did the pollera come to be the dress it is today? At what moment did the dress of our Spanish or mestizo grandmothers change into this lovely dress of the tropics? The answer lies in the passage of time, which allowed a gradual evolution of the pollera into what we have today. It is fitting to propose several questions concerning the origin and evolution of the pollera. Did it appear in Old Panama, as some people think, or in Acla and Nata? These regions are not the centers for making polleras today. Was it truly the dress for the servant class? If so, by what process was it adopted as the regular dress of peasants in the rural towns of the central provinces and mountain regions? Provinces of Los Santos and Herrera jealously guard the pollera tradition, so much so that models from these provinces have been adopted by all regions of the Republic. Why should these regions be the guardians and not the towns in which the pollera supposedly originated? Year after year, the seamstresses of the central provinces have sent innumerable polleras to Panama City, Colon, Chiriqui, and all points of the Isthmus. One must see the satisfaction and pride the woman dressed in pollera, empollerada, displays as she affirms that her dress was made in one of these provinces, and her confidence in the knowledge that her pollera follows all aspects of tradition. Since Herrera and Los Santos Provinces have conserved other folklore elements descending from Spain, it could explain why the pollera has been so carefully preserved in these areas.

A DEFINITION OF "POLLERA"

The dictionary defines "pollera" as a long, full skirt with many gathers. We commonly use "pollera" to mean any full skirt. As history and paintings clearly demonstrate, this style of skirt has been found in the women's dress of Europe since time immemorial. By the law of synthesis found among common people, the name for the skirt was applied gradually to the entire dress; there is nothing new, difficult, or novel about this process. None of the legends concerning the origin of the name "pollera" have any concrete base. All the suppositions and fantasies which pass freely from one person to another have no documented foundation. Furthermore, the dates given by some writers for the origin of the name, around 1900, are completely false; the name "pollera" was used for the typical dress in Panama as early as 1846.

EARLY REFERENCES TO THE POLLERA

Throughout the writings of a number of national investigators who have been interested in this theme, there are some early references to the pollera. These writers include Lady Matilde Obarrio de Mallet, whose writings were published in the Loteria magazine; Miss Nicolle Garay, who presented data in the book Tradiciones y Cantares de Panama written by D. Narciso Garay; Rodrigo Miro; Aurelio A. Dutary; Ruben D. Carles; D. Ernesto Morales; D. Roman B. Reyes; D. Samuel lewis; and poets such as Tomas Martin Feullet, Ana Isabel Illueca, and others-too many to enumerate. Among foreigners we have Armando Reclus, a Frenchman who came to explore the Isthmus and make early canal surveys for France.

Matilde Obarrio de Mallet affirmed that the pollera must have been worn in Old Panama. She did not offer any documents to substantiate her statement other than her own writings in which she delcared that her great-greandmothers had polleras. In addition to information concerning the pollera, Lady Mallet describes colonial life in Panama.

D. Samuel Lewis found a reference to the pollera in the Spanish newspaper Diario de Madrid, March 12 and 13, 1815. The article describes celebrations which occurred in Panama to commeorate the restoration of Fernando VII to the throne. He quotes, "The picture of the King was placed in an exquisitely decorated cart, which left from the courthouse on its way to Santa Ana, pulled by thirty women of the town richly dressed in polleras." If the statement is true, this is the oldest written reference to the pollera known to the present time. The article appeared in 1915, but the celebrations occurred in July, 1814, when D. Pedro de Olesarraga arrived on the Isthmus with the news of the restoration. The time of the celebration was seven years before Panama was to gain her independence from Spain in 1821. Already the pollera was known by the name we know it today and was the dress customarily used for festive occasions.

Armando Reclus, Director of the French Commission that made explorations throughout the Isthmus, described the pollera in almost complete detail. One must admire this French engineer who divided his time between scientific investigations, and a study of the customs which he found in his travels. Referring to celebrations commemorating Panama's independence from Spain, Reclus writes, "The colored ladies wear the pollera, a skirt gathered at the waist with large ruffles which are very full." Later, reviewing his experiences in the Darien, he adds, "the women wear the old dress of the criollas, that is, a white petticoat made of lightweight cotton, adorned with one or more ruffles on which are stamped brightly colored floral designs. Over the shorth sleeved blouse are three ruffles similar in appearance but so low that the upper chest and back are left practically nude. Their hair is parted down the middle, drawn to either side and braided if not too curly; but if the hair is extremely curly or wooly and cannot be braided, they divide the hair into ten sections and make little puffs of each one. Many of the women proudly wear large gold combs and earrings made in Choco area (Darien province), decorated with low cost pearls from the pearl fisheries of Panama, but the favorite arrangement is natural flowers in the hair. Frequently they wear a straw hat, similar in appearance to a man's hat; most of them do not wear shoes, reserving tiny green and pink slippers for fiestas." It would be difficult to find a better description of the pollera than this one difficult to find a better description of the pollera than this one presented by Reclus, who viewed his surroundings with sympathy and interest.

From the middle of the nineteenth century until the present, references to the pollera occur frequently. Designs made by artists around 1879 are still preserved, and their details coincide with descriptions of the dress written during that period. Two prints portraying a lady in pollera wearing a hat and shawl are included in N. Garay's book; the drawings were done by the author's father, D. Epifanio Garay. Another example occurs in the descriptions left by Armando Reclus

.

THE POLLERA, A DRESS OF THE COMMON PEOPLE

After reading the references left by writers interested in the pollera, it is possible to appreciate one important fact; every writer insisted that it was the dress of the lower classes. Lady Mallet described it as "the usual attire of the woman servants; it was especially the dress of the wet nurses who nursed the children of the family. The dress was generally white, almost without adornments. The cooks and wash ladies used colored skirts, usually purple, with a white blouse. . . It was a custom among some families to decorate the clothes of the domestic help with special types of handwork; some used an embroidery stitch, others a cross-stitch, and others applique."

If we pay special attention to the article in the Diario de Madrid referring to celebrations here in Panama mentioned by D. Samuel Lewis, we find it speaks of thirty women of the town richly dressed in polleras. It does not say the higher class, but the townspeople. Reclus also referred to the town: "the colored women wear the pollera" and "the women wear the old dress of the criollas." Who are the criollas for Reclus? The person born in America of Spanish descent? The native aristocracy? From the drawings he presents in his writings, the criolla appears to be neither Spanish nor the native aristocracy. The pollera was the dress of the common people, and here lies its strength, its continuity, and its permanence. As a creation of the common people, it reflected the vitality and spirit of that class, and extended into every city, town, and farm. From its humble beginning the pollera gradually was adopted by the women in the upper classes. Once accepting the pollera, this class adopted it as their own almost as if it had always been their traditional costume. Today the daughters of the aristocracy are just as proud to wear their polleras during days of fiestas as the women in rural areas.

VOCABULARY USED IN THE POLLERA

Arendela: Ruffles on the blouse, trimmed with insertion and edging laces.

Botones de Enaguas: Solid gold buttons used on the waistband of the skirt.

Botones de Filigrana: Gold filigree earrings shaped as buttons.

Cabestrillo: Gold chain adorned with numerous coins.

Cadena Bruja: Gold chain with "Z" shaped links.

Caden Chata Abierta: Same as the cadena chata except it is not closed. Each end has a dome-shaped tassel with thin, tearshaped pieces placed around the lower edge.

Calados: Neddlework used in the polleras in which the white background threads are removed and designs are worked around the open places.

Coca: Refers to the section of hair, tied in a bun behind the ears.

Cola 'e Pato: Gold necklace having wedge shaped links overlayed to make a thick cord.

Cuerpo de Camisa: Body or lower section of the blouse.

Cuerpo de Pollera: Upper tier of the skirt.

Dolores: Small gold squares, circles, half-moons, or shamrocks placed over the temples.

Dormilonas: Earrings.

Escapulario: Gold scapulary necklace.

Gallos: Ribbons placed at the center front and back of the waistband.

Guachapali: A fragile chain having thick gold links; it is said the links are shaped like seeds from the guachapali tree which grows profusely in Panama.

Guarda: The area covered with needlework on the blouse and skirt.

Media Naranja: A gold necklace having links simulating orange slices.

Melindre: Edging lace made locally on the mundillo.

Mosqueta: Gold and pearl rosette made as earrings, tembleques, or a pin worn in the front pompon of the blouse.

Monedero:Coin purse knitted from silk thread tucked over the waistband.

Mota: Wool pompons placed over the front and back neck openings of the blouse.

Mundillo: A small padded wheel set on a wooden stand used for making pollera laces.

Pajuela: Hair ornament shaped like a palm leaf.

Parches: Same as the dolores, small gold placques placed over the temples.

Peacillo: Narrow insertion lace made on the mundillo.

Peinetas de Balcon: Turtle shell combs having a gold border, sometimes decorated with pearls and other gold work.

Pelotas: The hair buns which are secured behind the ears.

Pepinos: Another name for the pelotas.

Picarona: The ruffle sewn around the lower edge of the montuna skirt.

Pretina de Boca: The neck binding in the blouse.

Puntada de Bolillo: Rolled hem stitch used for gathering the ruffles.

Rosario: The rosary, usually made in gold filigree.

Salomonica: A heavy, twisted chain having the same form as the columns on Solomon's temple.

Sombreada: Talco en sombra, white material appliqued on the wrong side of white cloth.

Solitaria: A long thin necklace resembling a tape worm.

Susto: The lower tier of the pollera skirt.

Talco: Applique needlework.

Tapabalazo: The lower section of the blouse yoke to which the ruffles are sewn.

Tapahueso: Black ribbon or ribbon-like gold chain fastened around the base of the neck to which is suspended a cross, medal, coin, or locket.

Tapa-oreja: Trembleques that cover the ears.

Tapa-pelota: Large trembleques used to cover the buns in the hair.

Trembleques: Hair ornaments made of wires and beads, resembling artificial flowers.

Zarcillos: Earrings.

Run your mouse over the picture to see another one!

The Tamborito

The Art of BEING Kuna

Folklore - The Revolt of the Chagres

Front Page - Fly With Me to the Canal Zone

Email: czangel@czbrats.com