October Bizarre Horror Issue

Interview #7: Michael A. Arnzen

We

are pleased to present you with this exclusive interview from the

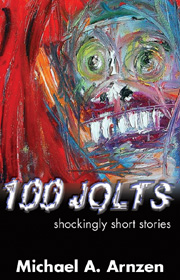

author of 100 Jolts: Shockingly Short Stories,

due April, 2004. Turn on the lights, grab a crucifix, and read on...

We

are pleased to present you with this exclusive interview from the

author of 100 Jolts: Shockingly Short Stories,

due April, 2004. Turn on the lights, grab a crucifix, and read on...

Q: You are quite prolific with both fiction and

poetry. Do you have a favorite between the two? Is there any difference

between creating verse and prose?

A: I'm bitextual. I write both ways.

But seriously: I'm just a lover of language. I enjoy both approaches

because they're different pathways that lead into the same dark

forest of the imagination. Writing is a way of discovering things

(like, just how sick I really can be) and I enjoy the expedition,

no matter what route I take. Poetry is something of an under-appreciated

and disreputable art lately, but its method frees me to explore

ideas because it has no hard-set rules—readers don't know

what to expect of it anymore. And neither do I as I write—it's

like building a magic puzzle box or something. Even in highly structured,

formal verse. The payoffs of poetry writing are different than storytelling,

but not any lesser or greater—just different. For me, storytelling's

pleasure lies is in the tricks of plot and the insights into character.

By writing fiction, I can inquire into why people commit the evil

that men do. And I can think more cinematically, not just capturing

an image but setting it into motion. Poetry can get away with being

less interested in person and more interested in abstract phenomena.

Regardless, in both, I find surprises as I go. That's the fun part.

And I've found that most of my readers are willing to go with me

there, either way.

Q: The Gorelets site managed to establish you as

a cutting edge author by featuring PDA material when few people

even knew what PDAs were. What has been the response to Gorelets?

A: The response was much stronger than I expected,

but I think publishing still has far to go before e-books and handheld

computers are really used to their fullest capacity. It starts with

realizing that the e-book format isn't better or worse—it's

just different than the printed book and requires a different way

of reading. It requires that readers change their habits of reading;

and maybe writers also could take the form of the medium into account.

Let me explain: I started Gorelets as a challenge to myself (to

write at least one good new poem a week) and a way to address the

lack of poetry I was seeing in the burgeoning e-book market. (Oh,

okay—just the subversive thought of some business type reading

a twisted poem during a board meeting sort of appealled to me, too).

One of the reasons e-books haven't taken off is that they're a little

cumbersome to read on a handheld computer or a cell phone. But not

poems! They can be short and sweet. But no one, really, seemed to

be writing them from what I could tell. So Gorelets began—little

horror poems, written to fit the small screens of Portable Digital

Assistants. The response was pretty strong because people with these

devices (Palm Pilots, Clie's, etc.) didn't have much cool content

to download beyond business and technology newspapers, so I was

providing something unique for them on a "subscription"

basis. Donations paid for everything; the site got more media coverage

than I expected. And I generated a book's worth of poems that sold

to Fairwood Press—http://www.fairwoodpress.com—who

is releasing it around Halloween. (Not to privilege one medium over

the other, Double Dragon Publishing—http://www.double-dragon-ebooks.com—will

release an e-book version with a bonus section of twenty-one poems

at the same time, too). I like to think that there's an audience

out there for horror and even horror poetry that just isn't being

reached by traditional publishing and I'm exploring new media as

a way to get there.

Q: Many people claim that it is the "violence

in media" which has spawned the seemingly desensitized public.

Is this true? Do you feel that readers are numbed to the horror

genre?

A: No. When I saw the film 28 DAYS LATER about,

well, 28 days ago, the audience in the theater was scared shitless.

They also harbored a silent respect of the movie—usually it's

all a silly spectacle for the theatergoers, but 28 DAYS LATER really

held their rapt attention. I take that as a positive sign of not

only the capacity of the horror genre to address our fears and desires

through violence, but also as a positive sign that humanity—even

in jaded teen culture—is still alert and sensitive to life.

If the public was desensitized, then terrorism wouldn't have the

hold it does over so many Americans. I don't think it's true that

the public is jaded; I think we have the attitude that we don't

want to >look< scared. That makes you vulnerable. Uncool.

Besides, violence in the media is sometimes more about the medium

itself as an art form—the way that lights flash out of a gun

barrel, the way bloodspatter artistically Pollocks on the wall behind

the victim...these are what we marvel at, abstractly, rather than

simply the act that happens in the narrative. The tragic loss of

life is sometimes placed secondary to other concerns. Or sometimes

it's impact is underscored by it. Art can do that. There's nothing

inherently wrong with doing so. It allows us to see death in a new

way. If any representation of violence is itself inherently bad,

then let's ban all photography, network news, and, hell, America's

Funniest Pets.

Q: Does surrealism—or the unexplainable—have

a place in horror? Or are readers only moved by tangible, real-world

terrors?

A: It's all always already surrealism, isn't it?

Life is but a dream. But to the point: Horror—the genre of

dark fantasy—has the capacity to be the most avant garde of

the popular genres, in my opinion. The connection is the psychology

of the nightmare. We dream about fish swimming in the air. Seems

normal in a dream. When we encounter it in art—while awake—we

call it "surreal." It's funny. Uncanny. Marvelous. But

then give that air fish teeth and have it swimming toward a human

on a hook and suddenly you've got a horror story. The momentary

confusion between reality and fantasy—felt as something uncanny—really

gives this stuff its impact. It's all about the unexpected. And,

like surrealism in the arts, horror tends to slap us in the face

and wake us up out of our habitual ways of seeing the world.

Q: One of the remarkable aspects of your writing

is the unyielding stream of untapped concepts. Where do you draw

your inspiration?

A: I'm deathly afraid of being boring. I'm afraid

of writing something that's been done already to death. The anxiety

of influence haunts me, so, likewise, I'm always striving to do

something new. Besides, I only respect writers who are original

and I strive to be one worthy of a reader's respect.

Reading inspires me a lot. And by "reading," I include

films, music, and TV.

Beyond that, the ideas come from everyday life, more often than

not. I always have my radar on, pinging reality for the unreal.

I look for things to twist as I make my way through the day; words

to play with; social habits that I can call attention to. I'm always

seeking to pull the rug out from people who take themselves too

seriously and I love to make them land on their chin. And I like

readers to feel like "anything can happen" so when I'm

planning to write, I constantly ask "What if anything could?"

Q: It seems uncommon to have a horror author entrenched

in the world of academia. How are you received by your peers? By

your students?

A: I'm very lucky to be working in a liberal arts

college that houses a program in writing >popular< fiction.

It's a dream job. Most of my peers understand that what I'm doing

is at once educational and important, so most respect it—usually

from a comfortable distance. But I always encounter a little bit

of academic snobbery here and there—I think that would happen

no matter what I did in academia. Likewise, there's a smattering

of suspicion among fiction writers, too, who wonder what on earth

an "academic" is doing writing horror stories... he can't

possibly be authentic, they suspect, because he's not out there

wrestling with his muse full time. Even some students harbor the

old "those who can, do; those who can't, teach" mentality.

But I only bump into these biases occasionally and I find them laughable,

really. The fact is, "those who can teach, teach." Regardless,

ultimately, I get respect from students and colleagues for being

both a widely published, award-winning author and a well-published

literary critic who can also teach without being boring. I'm in

the right place, across the board, and I'm thriving.

Q: There are rumors afoot about Mike Arnzen, the

rocker. I can only imagine what your songs would be about! Care

to comment?

A: Charles Manson was asked this same question

by Tom Brokaw once. Manson said, "Yeah, I do it. I do it. But

the way I do it, ain't the same way you guys do it. And the way

I do it scares you guys."

The way I play bass is pretty scary, too—like a percussive

instrument more than a guitar. Scary, because I'm quite terrible

at it. I can't really read music; I have no formal training at all;

I'm virtually tone deaf. I just like to bang on the thing and make

loud noises. But I did play in two bands—once in the Army,

and once in grad school—as a means toward escaping my general

suffering. Some of the sloppiest fun I've ever had. I still play

around with the guitar from time to time, but NEVER in front of

an audience. It's just a method of woolgathering for me. Maybe it

supports my poetry writing, I don't know.

It's ironic that you bring this up. Rock-and-roll was a recurring

motif in all the talk about horror writing at a recent conference

I attended in Pittsburgh (called Confluence). I saw Lawrence Connolly

do a one-man performance called "Songs of the Horror Writer"

equipped with nothing but a guitar and a microphone. He sang songs

about Lizzie Borden and insects and crimes of passion...and everybody

loved it. It was a hilarious subversion of the con's filk programming.

Later at that conference, I sat on a panel for "Horror in the

21st Century" with Lawrence and David Hartwell. David—a

senior editor at TOR and long-time scholar of the genre—was

very down on horror, claiming over and over again how dead it was.

He articulated how the market has bottomed out and everyone in the

room seemed depressed as hell by it all—which was pretty much

the truth. But in an effort of optimism, I suggested that horror

was the rock-and-roll of literature, and that it just comes in and

goes out of fashion, along with the latest taboos. David sang "The

Day the Music Died" in response, ending the panel on a bittersweet

note. Afterwards, I realized that I should have sang Neil Young

in response ("My My, Hey Hey"). Or maybe just classic

Ozzy.

Q: I’m living in a box. Somebody stops by

daily to shove water and scraps of food in through a crack. Eventually

they cram a book in for me to read by the marginal light provided

by said crack. What book should it be?

A: Houdini On Magic by Harry Houdini might help.

But if that's not available, then maybe something like Pilgrim at

Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard. It captures nature so well that you

wouldn't need to go outside of your box to touch it. Dillard's language

could make the blind see. The way she contemplates the meaning of

life and death is profound and spellbinding. You might think that

a book like Tinker Creek isn't a horror story, but it does contain

one of the best gross-out passage ever written—about a frog

whose body has been eaten from the inside-out. There's a lot of

grotesque description. No stylist I've read has more poetic power

of Dillard.

Q: Where can readers find your work?

A: I'm all over the map—from mass market

anthologies on the shelves at Barnes and Noble to small garage mimeograph

publications. It's hard to track me down, but I try to facilitate

the hunt for my work on my website, http://gorelets.com. Shocklines.com

is another good site for acquiring the books and magazines I appear

in. And I've got a number of e-books available at http://fictionwise.com.

Generally speaking, readers can expect tons of poetry short-term,

and more long fiction, long term. By the end of summer, my long-awaited

collection, Freakcidents: A Surrealist Sideshow, should be out from

DarkVesper Publishing. It's a book I'm really proud of and I'm hoping

others will see why. Then in the fall comes an e-book full of weird

poems about sports—aptly titled Sportuary—published

by CyberPulp Digital. That'll be exclusively in e-book form. And

then there's Gorelets: Unpleasant Poetry, which I already mentioned.

That'll be out in a neat collectable little chapbook by Fairwood

Press (and in e-book form from Double Dragon) around Halloween.

I've also just started putting up some interesting things for sale

on a section of my website called The Sickolodeon! Open 24 hours

at http://www.gorelets.com

Q: Can we look forward to any forthcoming projects?

A: I've been on a poetry and short-short kick for

a year and a half, and I have some plans for releasing some new

material exclusively on my website for The Sickolodeon (mostly multimedia

pieces), but I'm beginning to turn my focus back toward longer fiction.

I just wrapped up a collection of one hundred short-shorts called

100 Jolts which is making the rounds with new publishers. While

I market that, I'm putting together an as-of-now untitled horror

novella that will be released in a collectable chapbook next Winter

from Dark Animus in Australia and I'm still working on a twisted

kidnapping novel called Hoarder which I hope to finish before too

long and try to get into the dead mass market. If that market is

dead, well, it's coming back as one helluva zombie, that's all I

know.

Click the following links for two stories from Mike's forthcoming

collection, 100 JOLTS!

-A

Donation

-Mustachio

Moon