Britain was invaded early in its history by Celtic tribes originating from the european continent. They migrated from the Danube basin and the northern Alps from about the 6th to the 4th centuries b.c. The first arrivals were probably identified with the Picts or the Gaels. Known as the "painted people," the Picts covered their bodies with images or tattoos. The Gaels were less spectacularly adorned and were known for their fierce bravery in battle. The Scots were the third tribe of people. All originated in the Black Sea area and had migrated overland to the British Isles, crossing the channel at its narrowest point. In the ancient annals these same people were called scythians, kelts or keltoi, and other names to indicate their tribal nature and characteristics.

Most of them raised cattle, farmed to a limited degree, and had an extensive agricultural knowledge because of their long history observing the seasons, planets and stars, and the movement of the sun. But they also had a warlike constitution that was prone to violence. Their primary religion was pagan Druidism which admitted to worship of the great god Taranus and his pantheon. They believed also in a type of reincarnation that was based on a type of spirit worship and admitted to human possession by spirits of the dead. Eusebius lived three hundred years before St. Augustine was sent to Britain. He is known as the father of church history and explains in his works that the apostles "passed beyond the ocean to the Isles called the Brittanic Isles." It is also confirmed by early British historian Gildas who lived between 516 and 570 AD. He states that "these islands ... received the beams of light that is, the Holy precepts of Christ, the true Sun at the latter part, as we know, of the reign of Tiberius Caesar."

Tiberius Caesar reigned as Emperor when Christ was crucified. Gildas’ words indicate that he records what was regarded as the introduction of christianity in Britain was in "his day" a matter of "common intelligence". Tiberius reigned from about 14 to 37 AD and so Gildas says "in the latter part of the reign of Tiberius" to show his readers that christianity was introduced as early as 37 AD if not slightly before that time.

Julius Caesar was the first Roman Emperor to court the Celts for his own ambitions when he desired not only to unite Gaul but to invade the British Isles to extend the empire there. But it wasn't until Claudius led the Roman forces to conquor Britain in 43 BC. that occupation and civilization ensued. He inaugurated Roman Temple Worship at Camelodinum, but later the natives burned down the temple after its inauguration, and he and his forces withdrew from England. Although the legions sought to invade Wales and Scotland, they were intimidated by the wild erratic behavior of the tribal people they found there and chose to remain in the south instead, pursuing a civilizing influence, and promoting trade in various native products such as tin, other metals, chalk, etc.

The gospel came via Hebrew people who bore out this by two medals bearing the effigies of our Lord without a halo unearthed at Cork in 1812. This was found under the foundation of the very first Christian monastery built in Ireland. Another was discovered in the ruins of a druid circle in Bryngwin at Anglesey at the same time thereabouts.

The Hebrew letter "A" on the back and to the right of the image of Christ offers the date as the first year, after the other Hebrew letters which signify Jesus. The word Messiah is around the neck of the image and on the other side of the coin there is an inscription "Messiah, Prince, came in peace, and man, life for man became". The inscription on the other is different reading "Nought in Thee was found worthy of Divine Wrath."

When Agricola became governor of the Isles he assisted and promoted learning and culture among the people and gradually Roman ways were adopted which caused them to eventually reject all Druidism and it soon gradually faded out, replaced by more enlightened religious learning. Christianity made its appearance as early as the first or the second century, but primarily it remained among the educated and civilized classes in the Roman domain. Christianity's arrival instead of coming through a western gateway on the continent came directly from the East. Since there were few written documents at the time the domain of privilege and preservation resided with the educated, and the period remains a bit speculative.

We do know however that King Lucius asked for missionaries to Briton about 156 AD and that passages in both Tertullian and Origen regarding this were written in early and mid century 200 AD indicating that the Church was already being established in Briton during that time. Britain nonetheless was a fortress of 'secret christianity' since from the time of the Crucifixion of Christ up to the empirical proclamation establishing Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire by the Emperor, was a forbidden religion. Christians variously were blamed for the ills of the Empire. Persecutions and death abounded for any who professed openly such a christian faith, and so it existed in secret, its members were necessitated only to reveal through signs or symbols that they were christians.

The first english martyr was St. Alban. He was a pagan who helped a christian priest to avoid his persecutors by hiding him in his home and after he observed what was transpiring and learned the story of christianity, he himself converted to the faith. When soldiers invaded his home where the priest was hiding, St. Alban, dressed in the priest's clothing, was taken into custody and later martyred. His dominant and arduous faith steeled him, and after trying to convert the judge to christianity at his trial by reasoning and explaining the faith to him, Alban was killed.

In the reign of Diocletian in which a persecution ensued from 303-313 AD the British church supplied this list of martyrs: Amphibalus, Bishop of Llandaff, Alban of Verulam, Aaron and Julius the Presbyters of Caerleon, Socrates who was Archbishop of York, Stephen the Archbishop of London, Augulius his successor, Nicholas the Bishop of Penrhyn Glasgow, Melior the Bishop of Carlisle and about over 10,000 communicants in different levels of society at large. The Diocletian era according to a concensus of authorities fixes the establishment of christianity in Britain somewhere about the middle of the second century. From about 33 up to around 150, there is a space of 120 years for the propagation of faith and gradual national conversion. The person who baptised Lucius, or Lleeuer Mawr as he is called, who was the monarch responsible for establishing the church, was his uncle St. Timotheus, the son of Pudens and Claudia, who was brought up on "knees of the Apostles" as stated in the book "St Paul in Britain".

The zealous fervor of early converts is assessed by the fact that missionaries from Britain founded the Churches of Gaul (France), Lotharingia (Lorraine), and Helvetia (Switzerland). And the 29th Chapter of Acts which was only discovered in Turkey within the last century also relates that St. Paul himself traveled to the far countries and ended his journey at Lake Lucerne in Switzerland. That it is the same lake which is shaped like the crucified Christ from the air, and that Mount Pilate there was where Pilate himself committed suicide (see our page on Acts Chapter 29). So it was a good 5 to 5 & 1/2 centuries later that the first papal emissary set foot in Britain claiming a supremacy of the bishop of Rome which was rejected by the existent christian church. The mission ministry among the Angles, Jutes and Saxons had only recently begun when they immigrated and although of the same stock as the Britons, were still pagans. This enabled him to gain a footing and establish a Church on the Island but the nation was the last and least influenced by the papacy as evidenced by the annals.

About 314 AD a Council of Bishops met at Arles in Gaul. Three British bishops participated, coming primarily from York, London and Lincoln -- which clearly demonstrates the strength of the church in Britain and the extent of christianization there. In 359 AD, the English bishops also signified their approval of the Nicene Creed and it is from this time onwards that the Church in Britain was documented historically in both secular and ecclesiastical annals.

Saints Ninian and Patrick worked in the early missionary church, -- Ninian among the Picts at Whithern, and Patrick among the Irish Gaels. It was in about 401 AD that the Roman legions withdrew and the former territorial lands to the south again were invaded by the Scots from the north and west country. Each time they invaded, the civilized populace pleaded for assistance from Rome against these pagan hordes. But each time they received the assistance, it failed and in time they were warned by the Emperor that there would be no more help from the Empire again. The pagan strategy was such that each time the legions departed, the Scots and the Gaels waited until they were certain they would not return and then they would strike again. Eventually it fell to the populace to fight the pagans themselves to preserve their civilization intact.

When the errors of Arian and Apollinarus threatened the faith of the people, the Britons petitioned Gaul for two bishops to assist in teaching the correct faith and countering any heresy among the people and clergy. Again when the errors of Pelagius affected the faith these same bishops enlightened the people to the danger of that error as well. The heresies and their fight had a strong effect and it not only stimulated a desire in the people for a stronger, clearer faith understanding but resulted in an interest in education among the people to counter these errors.

When the Isles were invaded by the Angles and the Saxons from 449 onward the British believers were forced to retreat from them in order to preserve their lives and faith intact. Although there was a stronger organization to their politics the country became divided into small crude kingdoms. There also was an influx of renewed pagan belief in the religions of the northern peoples -- Thor and his pantheon -- but in 563 Saint Columba and 12 monks left the monasteries of Ireland and sailed to Iona where they built monasteries and began to convert the Scots to christianity and countered this pagan religion. It was St. Columba who left Ireland and the British Isles to venture further and convert King Brude. His journey took him variously to Burgundy, Switzerland and even to the very heart of Italy.

Saint David was born in Wales and he established 12 monasteries in the Isles. He succeeded the Bishop of Llandaff at Caerleon. His see was not only in south Wales, but he also affected Montgomeryshire and Herefordshire, and he traveled outside his orginal preserve into Devon and Cornwall too as far as Glastonbury.

It was not until Pope Gregory ordered Augustine to be consecrated in France and appointed him bishop to spearhead the conversion of Britain to christianity that the native faith in England became imperiled by foreign incursion. What was at stake was the independence of the British church and the bishops who were already laboring for the faith. They were from the original wave of conversions from the East, and they held the true faith, strongly refusing to allow it to be supplanted by the bishop of Rome with his own brand of christianity.

Augustine arrived along with 40 monks, settled on an island while waiting for permission to land, and thinking that the nation he was sent to was still totally pagan, he sought to win over the national population and especially the hierarchy of whoever existed from the native church which he found already there. Augustine first approached King Ethelbert of Kent, and he found that the Queen was a christian and indeed had already brought a bishop with her from the Frankish Kingdom when she came to England to marry. When the King found Augustine sincere, he allowed him to leave the island and to have a house at Canterbury in which his "see" would then be established. Although Augustine was accepted in the south he still needed to speak to the other celtic bishops from the north and west. He met with them in 603 under an oak at Gloucester. Seven of them came to meet him, along with many learned men from the monastery at Bangor.

On their journey to the meeting the men of religion counciled with a holy and respected hermit who warned them that if Augustine "were a man of God they should bow to his wishes," but if he was prideful and unyeilding "they should go against his wishes." For them to determine how this could be discovered, the hermit told them that if he refused "to rise from his chair and ignored them, then he was not a man of God." When the bishops saw him under the tree he did not rise to greet them and this angered the bishops considerably chich caused them to refuse to accept the authority of the pope or to change their customs of the faith which had already existed in the Isles since the time of their conversion. Augustine refused to compromise at all and also threatened them, but he could not unite the church under himself and there ensued another sixty years before the uniting of the church was finally completed.

The protest of the church signed by the Archbishop of St. David’s and six other bishops, as well as the abbot of Bangor, who conducted the conference with Augustine at the oak explains it clearly:

"Be it known and declared that we all, individually and collectively, are in all humility prepared to defer to the Church of God, and to the Bishop of Rome, and to every sincere and godly Christian, so far as to love everyone according to his degree, in perfect charity, and to assist them all by word and in deed, in becoming the children of God. But as for any other obedience, we know of none that he whom you term the pope or Bishop of Bishops, can demand."

Instead of being deterred by this failing of his diplomatic skills, he nevertheless continued to labor in the south and the celtic bishops labored in the north, apart in their religious duties.

The last bastion of paganism fell when Oswin was murdered in 651 AD and Penda who succeeded him was brought to his knees, which ended the wars for good. Christianity finally triumphed over the whole of Britain.

The early British, Irish, Scottish, and Gallic Churches formed one Church in one communion. The assumption of the Roman papacy about 606 to 610 is that the celtic church had previously been in communion with a primitive Roman church and the pope refused in the most insulting terms to acknowledge the prior existence of such a church. Of course the church which St. Augustine introduced into Britain in 597 AD particularly Kent and among the pagan saxons must be understood in this context as well. Such a primitive church existed already on a national scale and it was antagonistic to Rome in its new form and by the usurpation that Augustine represented to them.

St. Bede states that "Britons are contrary to the whole Roman world, and enemies to the Roman customs, not only in their Mass but in their tonsure." But Britons refused to recognise Augustine or to acquiesce in his demands. "We cannot," the bishops said "depart from our ancient customs without the consent and leave of our people." And Laurentius, Augustine's successor, speaks bitterly of the antagonism existing among the Scots -- "We have found the Scottish bishops worse even that the British" These Scots only occupied Dal-riata, which was the new territory that is now called Argyll.

Theodore of Tarsus put all of the church of the British Isles under the See of Canterbury and in 673 at the Synod of Hertford the Church of England succeeded in uniting and replacing the Old British Church as sole inheritor of the faith and hierarchy of Britain. At this same synod the territory was better organized into a number of sees for administrative purposes. But it was also Theodore himself who opposed Papal authority, since he felt as Archbishop of Canterbury that the Church in Britain had its own traditions that were not the same as that of the general Roman Church. This was because the original faith was received from the East directly and had no continental mediator.

Bishop Wilford of Northumbria who stood to lose much of his current territory by these divisions decided to journey to Rome in order to have the pope mediate the dispute and to decide on the issue in his favor. But the pope clearly had no authority to do this, since his see was at Rome, and all bishops were of equal status. Later Bishop Wilfred was imprisoned and finally banished, but before he died he made peace with the Church of England only on his deathbed.

After the Norman Invasion of 1066 there was another disagreement with Rome over Peter's Pence. Donations were to be sent to Rome to help rebuild St. Peter's Basilica which was in disrepair. Although William the Conqueror agreed to pay the pence to Rome he refused to accept the soveriengnty of Rome over the British Church. To make this clearly understood he instituted his own laws to demark the independence of the traditional English Church. So when during the reign of William II, Anselm was made Archbishop of Canterbury, it was Anselm's desire to place the church of England under Rome's authority, and there arose numerous problems. Only after two years when Anselm was dethroned and left England did the conflict lessen. But the king was killed by an arrow during a hunt and it was rumored that perhaps the arrow belonged to his brother Henry.

Henry I succeeded his brother William II and he sought to restore the church and the treasury to its former glory. Anselm returned to assist and take up his role again as Archbishop but Henry would not allow him to do so since he insisted only the king should decide and have authority over the church. He let Anselm remain without any authority and eventually he again left Britain. King Stephen succeeded to the throne then.

At Stephen's death about 1154 AD, Henry II was accorded the throne. Being a highly educated man he desired to restore the power of the Crown which seemed to have slipped during the last reign and he succeeded in this. He put forth the Constitutions of Clarendon which contained 16 points that clarified the relationship between Church and State. The purpose was to put the clergy directly under the authority of the king by transferring all criminal cases against the clergy to civil courts. Other articles dealt with the royal regulation of excommunications, the outlawing of appeals to the pope, and the reinstatement of the king with the right to appoint bishops and abbots.

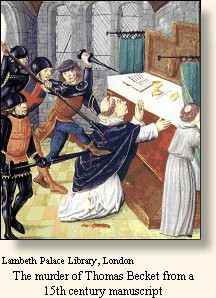

Thomas a Beckett was made Archbishop of Canterbury since he was a close friend of the king. But when he was consecrated, he refused to accept the document and in retaliation the king brought charges against him for a former post which he held as Chancellor. He was accused of mismanagement and squandering funds. Thomas fled to France and was granted asylum by the King of France. From there Thomas began to excommunicate any bishops who were disobedient to his rulings. When the Bishop of York coronated Henry's son, which was strictly the prerogative of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas sent papal letters suspending all the bishops and then he returned to England and was welcomed joyously by the people.

Since he refused to absolve any of the deposed bishops unless they pledge to the pope as supreme head of the church, four of Henry's knights murdered him at the altar on December 29th, 1170.

When miracles ensued at Becket's tomb and the pope canonized him as a saint, King Henry did public penance and allowed himself to be whipped publicly at the tomb in 1174. The tomb remained a shrine to the faith until the rise of Henry VIII when it was torn down. In 1205 during the reign of King John, when the Archbishop of Canterbury died, the monks of Christ Church Convent elected a successor in secret and immediately sent him to Rome to receive the pall at the hands of the pope himself. When John heard of this he had another bishop elected and so there was a dispute as to which of the two were the true Archbishop of Canterbury. The pope viewed this as an opportunity to exert authority and so he, instead of accepting either one of the electees, chose Stephen Langton, an English Cardinal as the successor to Canterbury.

This infuriated the king who then banished the monks of Christ Church to Flanders and warned that any popish adherents would be imprisoned, mutilated and executed. In 1208 the pope ignoring the kings outburst issued an interdict which closed all the churches of England and stopped the Eucharist, public prayer services and all christian burials. John in retaliation confiscated all property of the clergy, had them beaten, and even kidnapped the wives of the clergy as well for ransom, thus profiting by the dispute, -- to which the pope replied by excommunicating him.

When the pope threatened to send an invading army to England to restore order among the faithful and reinforce subservience to Rome, King John unable to raise an army to fight, finally received Stephen Langton as the Archbishop of Canterbury. The clergy were reinstated, and England and Ireland became vassals of the papacy as well, but not without turmoil within which continued to seethe. The king, the clergy, the nobles and the people felt this power over them was obtained at a price and that the king had no right to do this since the English people were free. The Church, taking the lead, called a meeting of the Barons and Clergy of St. Paul's and at the encouragement of the new Archbishop himself who informed them that the Charter of Henry I guaranteed them liberty to all people, they took a blood oath to not rest until the liberties were restored. Two years later at Runnymeade the Magna Carta was signed and the first and last paragraphs of this important document stated that the first place is granted to God and it is in the Church of England to be free with liberties unimpaired. And that the English Church is to be free from foreign influence, justice was for everyone, taxes must be collected by legal means and every man was entitled to a legal trial if needed. But Pope Innocent III declared the Magna Carta null and void and excommunicated the Barons who signed it. He suspended Langton as well who refused to publish the excommunications while he declared the king true to the church. Both King John and Pope Innocent died in 1216 AD and after their deaths peace reigned in England again once more.

Henry III succeeded John but he was only nine years old, and so he was influenced heavily by his advisers who actually ruled. Although the throne's power was reinforced by papal authority, the popes often demanded 10 percent of all money and possessions. But when Edward I came to the throne in 1271, he was called the greatest of the Plantagenet Kings, and it was he who strengthened Parliament so that English liberty would be increased. One of the consequences was that Parliament had representatives in the church itself in the offices of bishops and abbots who sought to remedy the sellout of the king to the pope. The statute of Mortmain was introduced which forbade any religious corporations from inheriting property or lands when the principal died. Many monasteries collected rents and taxes and sent money out of England because the orders were not native English orders but headquartered in other countries on the Continent. If this continued the economy of England would be impoverished completely. The popes however continued to remove assets and were the primary source of all claims of this sort. This amounted to great misery for the people -- anyone appointed by the pope to ecclesiastical office paid the pope his first year's benefice, and indulgences were being sold and the money sent to Rome, monastic houses owned one third of all lands, rents and taxes and they sent these to Rome too. Although many bishops held office, they rarely visited their charges, but collected all the privileges undeterred. These ills as well as the Crusades sapped the strength and vitality of the English people and society. Over the centuries new laws were passed to try to change this.

The War of the Roses was essentially a civil conflict. When it was over the people discovered the country and the church were extensively weakened. Henry VII came to the throne and sought an alliance with Spain by the marriage of Catharine of Aragon to his son Arthur. But when Arthur died, according to biblical tradition it was the brother (Henry VIII) who must sire children on the widow by marriage. Henry VIII being then only eleven was betrothed and finally married to Catherine so that the alliance would be preserved. When Henry reached majority he petitioned the pope to annul the marriage to his brother's widow. He wished to marry a woman of his own choice but the old Jewish law prevailed and to prevent this applying to him he wanted the annulment as quickly as possible.

Historically then the church in Britain existed from the earliest times to the present, and had a history of its own apart from the Roman Church. Vergil Polydore during the reign of Henry VII and after him Cardinal Pole in about 1555 AD both rigidly adhered to Roman Catholicism. Yet Cardinal Pole affirmed in his address to Parliament and Phillip and Mary that "Britain was the first of all countries to receive the Christian faith." Genebrard also relates that “The glory of Britain consists not only in this, that she was the first country which in a national capacity publicly professed herself Christian but that she made this confession when the Roman Empire itself was pagan and a real persecutor of Christianity."

The antiquity of the Church in England was questioned once by ambassadors from France and Spain at the Council of Pisa in 1417 AD. And the Council confirmed that the Church in England was one of the first to experience christianity after the crucifixion of Christ. These ambassadors also appealed to the Council of Constance in 1419 AD and the Council again confirmed the decision of former Council. This was confirmed again a third time at Siena in 1423 and a fourth time at Basle in 1431 -- that the British Church took precedence of all others because it was founded by Joseph of Arimathaea. This decision elucidated the fact to the Churches of France and Spain who were bound to give way in these points. Joseph of Arimathaea after the passion of Christ journeyed to Britain and being a well respected, high ranking, Roman provincial mining official, laid the church foundation. The jsuit Robert Parsons in the treatise "Three Conversions of England" admits in common with the great majority of Roman Catholic writers that christianity came to Britain directly from Jerusalem.

To Be Continued

Map of the early people.

Pictish Wolf

Saint Augustine

King Henry II

Murder of Thomas a'Becket

Pope Innocent III

King Henry VIII

Cranmer .... and ....... Wolsey