KAMIKAZE - Divine Wind ==========================================================================

The Japanese word kamikaze is usually translated as "divine wind" (kami is the word for "god", "spirit", or "divinity", and kaze for "wind"). The word kamikaze originated as the name of major typhoons in 1274 and 1281, which dispersed Mongolian invasion fleets.

The attempted Mongol invasions of Japan of 1274 and 1281 were major military invasions and conquests undertaken by Kublai Khan to take the Japanese islands after the capitulation of Goryeo (Korea). Despite their ultimate failure, the invasion attempts are of macrohistorical importance, setting a limit on Mongol expansion, and ranking as nation-defining events in Japanese history. The Japanese were successful, which was helped by the Mongols losing up to 75% of their invading troops and supplies both times on the oceans because of huge storms sinking the ships carrying the invasion force. The invasions are referred to in many works of fiction, and are the earliest events for which the word kamikaze, or "divine wind", is widely used. In addition, with the exception of the Occupation at the end of World War II, these failed invasion attempts are the closest Japan has ever come to being invaded within the last 1500 years.

From a military perspective, the failed invasions of Kublai Khan were the first of only two instances (the other being the Japanese invasion of Korea in 1592) where the samurai would fight foreign troops rather than amongst themselves. It is also the first time samurai clans fought for the sake of Japan itself instead of more narrowly defined clan interests. The invasions also exposed the Japanese to an alien fighting style which, devoid of the single combats that characterized traditional samurai combat, they saw as inferior.

This also marks the first use of the word kamikaze ("Divine Wind") It also perpetuated the Japanese belief that they could not be defeated, which remained an important aspect of Japanese foreign policy until the end of the Second World War. The invasions were also the only time that enemy nations would mount an invasion of any of the main four islands of Japan.

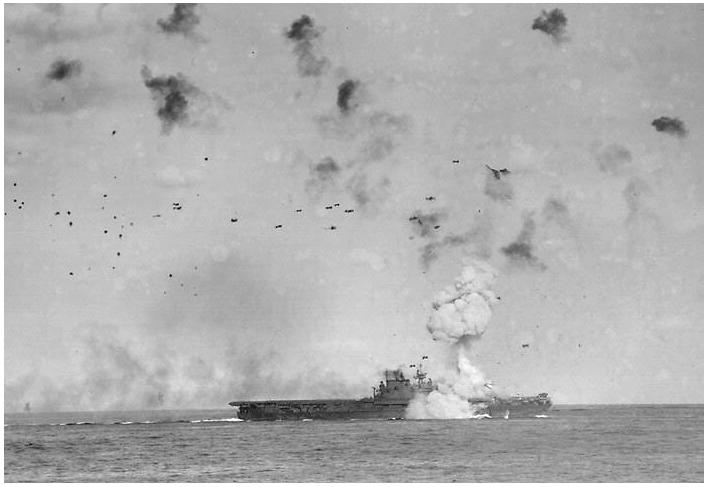

The Kamikaze ("divine wind") were suicide attacks by military aviators from the Empire of Japan against Allied shipping, in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, their goal was to destroy as many enemy warships as possible.

In Japanese, the formal term used for units carrying out suicide attacks during 1944-45 is tokubetsu kogeki tai, which literally means "special attack unit". This is usually abbreviated to tokkotai. More specifically, air suicide attack units from the Imperial Japanese Navy were officially called shinpu tokubetsu kogeki tai ("divine wind special attack units"). Shinpu is the on-reading (on'yomi or Chinese-derived pronunciation) of the same characters that form the word kamikaze in Japanese. During World War II, the pronunciation kamikaze was used in Japan only informally in relation to suicide attacks, but after the war this usage gained acceptance worldwide and was re-imported into Japan. As a result, the special attack units are sometimes known in Japan as kamikaze tokubetsu kogeki tai.

Kamikaze pilots would attempt to intentionally crash their aircraft — often laden with explosives, bombs, torpedoes and full fuel tanks – into Allied ships. The aircraft's normal role was essentially converted to that of a manned missile in a desperate attempt to reap the benefits of greatly increased accuracy and payload over that of a normal bomb. The goal of crippling as many Allied capital ships as possible was considered critical enough to warrant the sacrifice of an aviator and his aircraft.

These attacks, beginning in October 1944, followed several critical military defeats for Japan. A combination of a decreasing capacity to wage war – along with the loss of experienced pilots – and rapidly declining industrial capacity relative to the United States, as well as the Japanese government's reluctance to surrender, led to the use of kamikaze tactics as Allied forces advanced towards the Japanese home islands.

Kamikazes were the most common and best-known form of Japanese suicide attack during World War II. They were similar to the "banzai charge" used by Japanese soldiers. In addition, the Japanese military used or made plans for various suicide attacks, including submarines, human torpedoes, speedboats and divers.

The tradition of suicide instead of defeat and capture and perceived shame was deeply entrenched in the Japanese military culture. For instance, it was one of the main traditions in the Samurai life and the Bushido code, particularly loyalty and honor unto death.

Prior to the formation of kamikaze units, deliberate crashes had been used as a last effort when a pilot’s plane was severely damaged and he did not want to risk being captured — this was the case in both the Japanese and Allied air forces. According to Axell & Kase, these suicides “were individual, impromptu decisions by men who were mentally prepared to die.” In most cases, there is little evidence that these hits were more than accidental collisions, of the kind likely to happen in intense sea-air battles. One example of this occurred on December 7, 1941 during the attack on Pearl Harbor. First Lieutenant Fusata Iida’s plane had been hit and was leaking fuel, when he apparently used it to make a suicide attack on Kaneohe Naval Air Station. Before taking off, he had told his men that if his plane was badly damaged he would crash it into a "worthy enemy target".

During 1943-44, United States forces were steadily advancing towards Japan. Japan's fighter planes were becoming outnumbered and outclassed by newer U.S.-made planes, especially the F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair. The Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) was worn down by air battles against the Allies during the Solomons and New Guinea campaigns. Finally, in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the Japanese lost over 400 carrier-based planes and pilots, an action referred to by the Allies as the "Great Marianas Turkey Shoot". Skilled fighter pilots were also becoming scarce. Tropical diseases, as well as shortages of spare parts and fuel, made operations more and more difficult for the IJNAS.

On June 19, 1944, planes from the carrier Chiyoda approached a US task group. According to some accounts, two made suicide attacks, one of which hit the USS Indiana.

The important Japanese base of Saipan fell to the Allied forces on July 15, 1944. Its capture provided adequate forward bases which enabled U.S. air forces using B-29 Superfortress long-range bombers to strike the Japanese home islands. After the fall of Saipan, the Japanese high command predicted that the Allies would try to capture the Philippines, which were strategically important because of their location between the oil fields of Southeast Asia and Japan.

In August 1944, it was announced by the Domei news agency that a flight instructor named Takeo Tagata was training pilots in Taiwan for suicide missions.

Another source claims that the first kamikaze mission occurred on September 13, 1944. A group of pilots from the army's 31st Fighter Squadron on Negros Island decided to launch a suicide attack the following morning. First Lieutenant Takeshi Kosai and a sergeant were selected. Two 100-kilogram bombs were attached to two fighters, and the pilots took off before dawn, planning to crash into carriers. They never returned, and there is no record of an enemy plane hitting an Allied ship that day.

According to some sources, on October 14, 1944, USS Reno was hit by a deliberately-crashed Japanese plane. However, there is no evidence that this was a deliberate attack.

Captain Masafumi Arima, the commander of the 26th Air Flotilla (part of the 11th Air Fleet), is also sometimes credited with inventing the kamikaze tactic. Arima personally led an attack by about 100 Yokosuka D4Y Suisei (or "Judy") dive bombers against a large Essex class aircraft carrier, USS Franklin near Leyte Gulf, on (or about, accounts vary) October 15, 1944. Arima was killed and part of a plane hit the Franklin. The Japanese high command and propagandists seized on Arima's example: he was promoted posthumously to Admiral and was given official credit for making the first kamikaze attack. However, it is not clear that this was a planned suicide attack, and official Japanese accounts of Arima's attack bore little resemblance to the actual events.

On October 17, 1944, Allied forces assaulted Suluan Island, beginning the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The Imperial Japanese Navy's 1st Air Fleet, based at Manila was assigned the task of assisting the Japanese ships which would attempt to destroy Allied forces in Leyte Gulf. However, the 1st Air Fleet at that time only had 40 aircraft: 34 Mitsubishi Zero carrier-based fighters, three Nakajima B6N torpedo bombers, one Mitsubishi G4M and two Yokosuka P1Y land-based bombers, with one additional reconnaissance plane. The task facing the Japanese air forces seemed impossible. The 1st Air Fleet commandant, Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi decided to form a suicide attack force, the Special Attack Unit. In a meeting at Mabalacat Airfield (known to the U.S. military as Clark Air Base) near Manila, on October 19, Onishi told officers of the 201st Flying Group headquarters: "I don't think there would be any other certain way to carry out the operation [to hold the Philippines], than to put a 250 kg bomb on a Zero and let it crash into a U.S. carrier, in order to disable her for a week."

Commander Asaiki Tamai asked a group of 23 talented student pilots, all of whom he had trained, to volunteer for the special attack force. All of the pilots raised both of their hands, thereby volunteering to join the operation. Later, Tamai asked Lt Yukio Seki to command the special attack force. Seki is said to have closed his eyes, lowered his head and thought for ten seconds, before saying: "Please do appoint me to the post." Seki thereby became the 24th kamikaze pilot to be chosen. However, Seki later wrote: "Japan's future is bleak if it is forced to kill one of its best pilots. I am not going on this mission for the Emperor or for the Empire... I am going because I was ordered to!" During his flight, his commanders heard him say "It is better to die, rather than to live as a coward."

The establishment of kamikaze forces required recruiting men for the task — this proved easier than the commanders had expected. Qualifications were simple: "youth, alertness and zeal. Flight experience was of minimal importance and expertise in landing a luxury". Captain Motoharu Okamura commented that "there were so many volunteers for suicide missions that he referred to them as a swarm of bees, explaining: ‘Bees die after they have stung’".

When the volunteers arrived for duty in the corps there were twice as many persons as aircraft. "After the war, some commanders would express regret for allowing superfluous crews to accompany sorties, sometimes squeezing themselves aboard bombers and fighters so as to encourage the suicide pilots and, it seems, join in the exultation of sinking a large enemy vessel". Many of the Kamikaze believed their death would pay the debt they owed and show the love they had for their families, friends, and emperor. "So eager were many minimally trained pilots to take part in suicide missions that when their sorties were delayed or aborted, the pilots became deeply despondent. Many of those who were selected for a bodycrashing mission were described as being extraordinarily blissful immediately before their final sortie".

Tokkôtai pilot training, as described by Kasuga Takeo, generally "consisted of incredibly strenuous training, coupled with cruel and torturous corporal punishment as a daily routine." Irokawa Daikichi, who trained at Tsuchiura Naval Air Base, recalled that he "was struck on the face so hard and frequently that [his] face was no longer recognizable." He also wrote: "I was hit so hard that I could no longer see and fell on the floor. The minute I got up, I was hit again by a club so that I would confess." This brutal "training" was justified by the idea that it would instill a "soldier's fighting spirit." However, daily beatings and corporal punishment would eliminate patriotism among many pilots.

Pilots were given a manual which detailed how they were supposed to think, prepare, and attack. From this manual, pilots were told to "attain a high level of spiritual training", and to "keep [their] health in the very best condition". These things, among others, were meant to put the pilot into the mindset in which he would be mentally ready to die.

The tokkôtai pilot's manual also explained how a pilot may turn back if the pilot could not locate a target and that "[a pilot] should not waste [his] life lightly". However, one pilot who continually came back to base was shot after his ninth return.

The manual was very detailed in how a pilot should attack. A pilot would dive towards his target and would "aim for a point between the bridge tower and the smoke stacks". Entering a smoke stack was also said to be "effective". Pilots were told not to aim at a ship's bridge tower or gun turret but instead to look for elevators or the flight deck to crash into. For horizontal attacks, the pilot was to "aim at the middle of the vessel, slightly higher than the waterline" or to "aim at the entrance to the aircraft hangar, or the bottom of the stack" if the former was too difficult.

The tokkôtai pilot's manual told pilots to never close their eyes. This was because if a pilot closed his eyes he would lower the chances of hitting his target. In the final moments before the crash, the pilot was to yell "Hissatsu" at the top of his lungs which roughly translates to "Sink without fail".

By the end of World War II, the IJN had sacrificed 2,525 kamikaze pilots, and the IJA had lost 1,387.

The number of ships sunk is a matter of debate. According to a wartime Japanese propaganda announcement, the missions sank 81 ships and damaged 195, and according to a Japanese tally, suicide attacks accounted for up to 80 percent of the U.S. losses in the final phase of the war in the Pacific. In a 2004 book, World War II, the historians Wilmott, Cross & Messenger stated that more than 70 U.S. vessels were "sunk or damaged beyond repair" by kamikazes.

Official US sources put the toll much lower. According to a U.S. Air Force webpage: Approximately 2,800 Kamikaze attackers sunk 34 Navy ships, damaged 368 others, killed 4,900 sailors, and wounded over 4,800. Despite radar detection and cuing, airborne interception and attrition, and massive anti-aircraft barrages, a distressing 14 percent of Kamikazes survived to score a hit on a ship; nearly 8.5 percent of all ships hit by Kamikazes sank.

Australian journalists Denis and Peggy Warner, in a 1982 book with Japanese naval historian Seno Sadao (The Sacred Warriors: Japan’s Suicide Legions), arrived at a total of 57 ships sunk by kamikazes. However, Bill Gordon, a US Japanologist who specialises in kamikazes, states in a 2007 article that 49 ships were sunk by kamikaze aircraft. Gordon says that the Warners and Sadao included eight ships that did not sink.

The Ohka suicide rocket-missles of the Thunder-Gods Corps.

The Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka, ("cherry blossom" ) was a purpose-built, rocket powered kamikaze suicide missile employed by Japan towards the end of World War II. The United States gave the aircraft the name Baka (Japanese for "idiot").

It was a manned flying bomb that was carried underneath a Mitsubishi G4M "Betty", Yokosuka P1Y Ginga "Frances" (guided Type 22) or planned Heavy Nakajima G8N Renzan "Rita" (transport type 43A/B) bomber to within range of its target; on release, the pilot would first glide toward the target and when close enough he would fire the Ohka's rocket engine and guide the missile towards the ship that he intended to destroy. The final approach was almost unstoppable (especially for Type 11) because the aircraft gained tremendous speed. Later versions were designed to be launched from coastal air bases and caves, and even from submarines equipped with aircraft catapults, although none were actually used this way.

Conceived by Ensign Mitsuo Ohta of the 405th Kokutai, and aided by students of the Aeronautical Research Institute at the University of Tokyo, Ohta submitted his plans to the Yokosuka research facility. The Imperial Japanese Navy decided the idea had merit and Yokosuka engineers of the First Naval Air Technical Bureau (Kugisho) created formal blueprints for what was to be the MXY7. The only variant which saw service was the Type 11, and was powered by three Type 4 Mark 1 Model 20 rockets. 150 were built at Yokosuka, and another 600 were built at the Kasumigaura Naval Air Arsenal.

Essentially a 1200 kg (2,646 lb) bomb with wooden wings powered by three Type 4 Model 1 Mark 20 solid-fuel rocket motors, the Type 11 achieved great speed but with limited range. This was problematic as it required the slow heavily laden mother aircraft to approach within 20 nautical miles (40 km) of the target, making them very vulnerable to defending fighters.

It appears that the operational record of Ohkas used in action includes three ships sunk or damaged beyond repair and three other ships with significant damage. Seven US ships were damaged or sunk by Ohkas throughout the war.

=================================================================================

NB: The above text has been collected / excerpted / edited / mangled / tangled / re-compiled / etc ... from the following online sources :

KAMIKAZE - Divine Wind - wikipedia article #1

KAMIKAZE - Divine Wind - wikipedia article #2

OHKA suicide rocket-missle - wikipedia article #3