IJN Long Lance - Type 93 Torpedo ==========================================================================

A torpedo is a self-propelled projectile carrying a warhead which detonates against a ship's side below the waterline. It was the most destructive naval weapon of the Second World War and the best of these was the Japanese Long-Lance.

In 1941 the Japanese Navy was the third largest navy in the world, after the US Navy and the Royal Navy. It had 100 destroyers, 18 heavy cruisers and 18 light cruisers. Most destroyers and cruisers were fitted with the 24-inch Long Lance torpedo. This oxygen-powered weapon could deliver a 1,000lb warhead at 49 knots over almost 11 miles.

At the outbreak of the war, the Japanese Navy possessed some of the world's finest torpedoes, including the fabled Long Lance. The quality of these weapons was no accident, but rather the result of Japan's intensive efforts during the 1920's and 30's to make good the shortcomings of her battle fleet. Laboring as she did under the unfavorable 5:5:3 ratio of capital ships imposed by the Washington Naval Treaty, Japan would most likely be at a disadvantage in any Pacific conflict with the United States. She also knew well enough that the U.S. modeled its fighting doctrine on the famous 'Plan Orange', which called for an advance of the American battle fleet across the Pacific to relieve the Phillipines. It was anticipated that at some location in the Western Pacific a decisive battle would be fought. In Japan's view, some means must be found to offset its disadvantage in capital ships before this battle occurred, or its inferior batle line would be destroyed by the American force. Torpedo tactics and night combat were seized upon as one way to whittle down the American battle line as it made its way across the Pacific. Accordingly, Japan worked diligently to develop the tactics needed to implement this new doctrine, and also to create the weapons with which to carry it out. The result was that Japanese torpedoes showed a steady progression of improvements throughout the 1930's, culminating in the devlopment of the famous 'Long Lance' in 1935.

Designing and perfecting the Long Lance required solving some extremely difficult technical problems, most of which centered around the usage of pure oxygen as a fuel (rather than compressed air). Compressed air is nearly 77% nitrogen, which is useless for combustion, and also contributes to the visibility of the torpedo by leaving a bubble track on the surface. The usage of pure oxygen promised far greater power and propulsive efficiency, but it came with certain costs. The most glaring of these was how to use pure oxygen safely aboard a ship or submarine, given its inherently inflammable nature. Premature detonation of the torpedo upon firing was also a problem. However, the Japanese overcame these hurdles. Further, through meticulous live-testing of their weapons against ship targets, they perfected a warhead detonator that was rugged and reliable (The U.S. Navy's BuOrd could certainly have taken a lesson or two here). The resulting weapon, the Type 93 torpedo, was fantastically advanced in comparison with its Western counterparts, possessing an unequaled combination of speed, range, and hitting power. This weapon, coupled with the flexible battle tactics practiced by Japan's cruisers and destroyers, led to victory after victory in the early stages of the war. Only as American radar and gunfire control became increasingly sophisticated would the Japanese advantage in night battles begin to disappear, and even then a Long Lance-armed Japanese destroyer was still a thing to be feared.

Bottom line: the US fish had a decent-sized warhead, but nowhere near the range of the Long Lance, and the reliability was not as good. I know which one I'd rather be shootin', pardner...

Japanese warships mounted their torpedoes in several different types of mounts, ranging from dual-tube configurations, all the way up to quintuple tube mounts. Destroyers most often carried triples (in the Fubuki's (1928) thru the Hatsuharu's (1935)) and quads (Shiratsuyu (1936) on) thereafter (except for Shimakaze, which carried three quintuple mounts). Cruisers carried doubles, triples, or quadruples.

The Type 93 was a 610 mm (24 inch) diameter torpedo of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Called the "Long Lance" by most modern English language naval histories (a nickname given by Samuel E. Morison, a historian who spent much of the war in the Pacific theater), it was the most advanced torpedo in the world at the time.

The Type 93's development (in tandem with the submarine model, Type 95) began in Japan in 1928, under the auspices of Rear Admiral Kaneji Kishimoto and Captain Toshihide Asakuma. At the time, the most powerful potential enemy of the Japanese Navy was the United States Navy's Pacific Fleet. U.S. doctrine, presuming a move by Japan against the Philippines (then a U.S. possession), called for the U.S. battle line to fight its way across the Pacific Ocean, relieve or recapture the Philippines, and destroy the Japanese fleet. Since Japan possessed fewer battleships than the United States, the Japanese Navy planned to use light forces such as cruisers and destroyers to whittle down the U.S. fleet in a succession of night actions. After U.S. numbers were sufficiently reduced, Japan would commit her own fresh and undamaged battleships to finish off the U.S. remnants in a climactic engagement. (Curiously, this is essentially what American War Plan Orange expected.)

The Japanese Navy invested heavily in developing the torpedo; it was one of the main naval weapons capable of damaging a battleship. Japan's research focused on using compressed oxygen instead of compressed air for its propulsion oxidizer, feeding this into an otherwise normal wet-heater engine. Air is only about 21% oxygen, so a torpedo using compressed oxygen instead of air would hold about five times as much oxidizer in the same size tank. This meant that the torpedo could travel further and faster. Additionally, uncombusted normal air, principally nitrogen, bubbled to the surface and left a trail pointing back at the launcher. With oxygen, the gas was almost completely burned and left an almost invisible bubble trail.

However, compressed oxygen is more dangerous to handle and it required lengthy testing and experimentation for operational use to be possible. Finally, engineers discovered that by starting the engine with compressed air and gradually switching over to pure oxygen, they were able to overcome the uncontrollable explosions that had hampered its development. To conceal the use of oxygen, the oxygen tank was named Secondary Air Tank. It was first deployed in 1935.

The Type 93 had a maximum range of 40,000 m (21.5 nm) at 38 knots (70 km/h) with a 1,080 lb (490 kg) warhead. By contrast, the standard U.S. destroyer-launched torpedo of World War II, the Mark XV, had a maximum range of 15,000 yards (13,500 m) at 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h), or 6,000 yards (5,500 m) at 45 knots (83 km/h), with a 825 lb (375 kg) warhead. Too large to fit in the standard 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes on submarines, the Type 93 was usually launched from 24-inch (610 mm) tubes mounted on the decks of surface ships.

The Japanese Navy outfitted many of its destroyers and cruisers with Type 93s. The long range, speed, and heavy warhead of the Type 93 gave these warships a formidable punch. Most also carried reloads and equipment for rapidly inserting them into the tubes—a practice unique among navies of the era.

In early battles, Japanese destroyers and cruisers were able to launch their torpedoes from over 20,000 metres away at unsuspecting Allied ships that were attempting to close to gun range, expecting torpedoes to be fired at less than 10,000 metres, the typical range of that era. The losses sustained in such engagements led to a belief among the Allies that the torpedoes were being fired from submarines operating in concert with the surface ships, but at much closer ranges. On rare occasions, the very long range of the torpedo caused it to strike a ship that was far behind the intended target. The Type 93's capabilities were not recognized by the Allies until one was captured intact in 1943.

A 17.7 inch (450 mm) version designated the Type 97 was later developed for use by midget submarines, but it was not a success and was replaced operationally by the Type 91. A 21 inch (53 cm) version for use by submarines was designated Type 95 and was highly successful.

The Type 93 was not without faults. They had a significant tendency to explode, compared to compressed air weapons, and a single explosion from one was enough to sink destroyers or heavily damage cruisers that carried them. As air raids became common, captains of destroyers under attack were faced with the decision of whether to ditch the torpedoes to better survive the air attack, or carry them to have much better odds against heavier or more numerous opponents in surface battles.

Japanese destroyers in World War II enjoyed well-deserved reputations for excellence in combat, particularly in night fighting and torpedo actions. Yet the fate of Japan's 'tin cans' was a grim one. Japan began the war with 113 destroyers, and built 63 more during the course of the conflict. Of these, a total of 134 were sunk, and many of the survivors were badly damaged by the end of the war. Allied aircraft and submarines, in particular, exacted a very heavy toll.

IJN Type 93 Long Lance Torpedo ==========================================================================

In 1942 few Americans had ever heard of Guadalcanal, The Slot, the Solomon Islands, or one unassuming island called Savo that found itself squeezed between the aforementioned Guadalcanal (off the shoulder of Cape Esperance), and Florida Island. The only real asset these steaming jungle-bound lumps of earth offered was either their strategic position or the fact that airfields could be, or had been, carved from their inhospitable surface. Where there is land, of course, there are Marines and Soldiers, but where there are islands, there must naturally come sailors and ships. It was all very simple; the Japanese held the Solomons and the Americans wanted them, starting with the Canal.

Once the Japanese found American marines had invaded Guadalcanal they began a fierce campaign to dislodge them from the island. The Imperial Japanese Navy’s role in this effort was to destroy the enemy’s landing force and supply the Japanese army units fighting not only the Americans, but also the jungle.

Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa led the first major attempt (Japanese army and naval aircraft had struck first but they lacked the numbers and firepower to drive off the Americans), from Rabaul on August 7, 1942. In late afternoon the heavy cruiser Chokai (flying Mikawa’s flag) leading light cruisers Tenryu and Yubari, and the destroyer Yunagi, sailed out of Simpson Harbor. Four hours later they rendezvoused with Cruiser Division 6, increasing the task force by an additional four heavy cruisers.

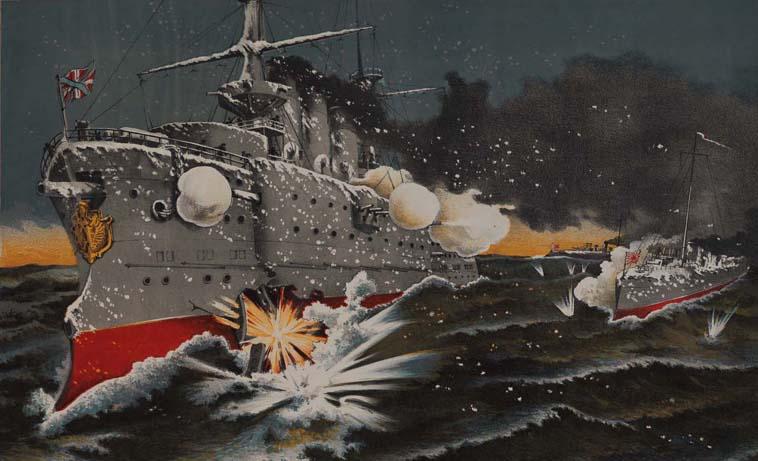

The three allied forces (Australian and American) guarding the waters around Savo were, combined, on paper, more powerful than the Japanese task force that approached the area that would soon be known as Iron Bottom Bay (or Iron Bottom Sound.) The Northern Force, closest to Florida, consisted of three heavy cruisers and three destroyers. The Southern Force, just off the Canal, had a similar complement. The Eastern Force, which would not be involved in the engagement, consisted of two cruisers and two destroyers. The heavy cruisers mounted 8 and 5-inch guns in a variety of complements, depending on the class and nationality. The destroyers, an all-American show, carried 5-inch guns and an array of torpedoes. The Americans also had the advantage of radar although it, and its potential, were fairly new to the sailors using this wondrous weapon, so while it gave them the capability to see over the horizon, it was still an imperfect instrument. What the Japanese brought to the engagement was a startling, and very successful, introduction to the Long Lance torpedo.

This was not the name that the Imperial Japanese Navy gave this deadly weapon; that title, ironically, came from noted naval historian Samuel Eliot Morrison. The Long Lance was a brute, a 24” diameter at its bulbous nose, nearly 30 feet long; it weighed almost 3 tons and carried an explosive payload a shade over half-a-ton. It was described as “the most lethal torpedo in the world.” Later versions saw the Type 93 modified to carry a human pilot—the Kaiten manned torpedo, but for now this unconventional torpedo was going to be used in a most conventional way: to sink enemy ships. While most torpedoes were driven by compressed air, a means of propulsion that left a bubbly trail right back to the sender, the Type 93 used compressed oxygen. Air is only about 21% oxygen and is inert. Oxygen can be explosive. It was discovered after a series of tests that if the Type 93 started its engine with compressed air and then switched over to oxygen, the likelihood of explosion as the torpedo was launched was greatly reduced. Its speed, when launched, was phenomenal—the Type 93 could travel about twelve miles at top speed, 49 knots or approximately 25 miles at 36 knots. Both American and British torpedoes were smaller, slower and had only the fraction of the range. Torpedoes used by the U.S. Navy the first two years of the war were unreliable; the exploder and depth regulating mechanism often failed to function as designed. The Americans had decided that torpedo tubes aboard anything larger than a destroyer were a waste of space and armament so only the smaller vessels carried torpedo tubes. At one time, as unlikely as it seems, even some battleships had underwater tubes but then the sight of big guns swinging into action dazzled the navy brass, and they were removed.

Every Imperial Japanese Navy vessel that steamed to meet the combined fleet in the darkness around Savo Island carried torpedoes. Not all were Long Lance because these monsters required special tubes and other equipment and at least two of the vessels, the Tenryu and the Yunagi, were as yet unfitted. But 52 of the 62 torpedo tubes aboard the Japanese vessels carried the Long Lance. A weapon, any weapon, no matter how much potential it promised is only as good as the warriors that employ it, and unfortunately for the crews of the H.M.A.S. Canberra, U.S.S. Quincy, U.S.S. Vincennes, and U.S.S. Astoria, the Japanese sailors were very, very good.

Before the war, the Japanese navy had practiced night fighting religiously. They had also conducted aggressive maneuvers in severe weather that resulted in the loss of men but reinforced the ability to fight in a coordinated fashion regardless of the circumstance. Japanese optics were substantially better than American, as were Japanese star shells, which illuminated enemy ships at night. In comparison during the Battle of Savo Island, only six of the forty-four star shells fired by American vessels worked. The Japanese also used searchlights to their fullest advantage, sometimes blinding the crews of opposing ships. The tactic when approaching an enemy force at night was simple; get within torpedo range, utilize these weapons first, and then engage with guns.

In the early morning of August 9, 1942 the stage was set in the waters around Savo Island. At 0043, the U.S.S. Blue, a Craven Class DD, was spotted by the lookouts on the lead Japanese ship, the Chokai. Mikawa ordered a course adjustment, and the Japanese fleet slipped between the Blue and the U.S.S. Ralph Talbot. Minutes later Mikawa was notified that there were enemy ships south of Savo Island. The Americans and Australians are not aware of the enemy’s approach. Mikawa ordered torpedoes and independent fire as the Japanese closed on the unsuspecting combined fleet at 1,400 yards a minute. Captain Toshikazu Ohme remembered the action. “Soon after we passed around Savo Island, we sighted your southern force of cruisers. About two minutes after sighting we fired torpedoes and then opened with guns.” It was the Imperial Navy’s classic tactic, and it worked splendidly that day.

Two torpedoes struck H.M.A.S. Canberra and shells destroyed her bridge, killing or wounding everyone at their station. She was out of the fight before having time to get into the fight. U.S.S. Patterson was trapped by enemy searchlights and struck several times. U.S.S. Chicago, a Northampton Class heavy cruiser, had a portion of her bow blown off by a Long Lance. After six minutes, Mikawa turned on the Northern Force, who, inexplicably had not been warned of the enemy’s approach.

Astoria found out the hard way, falling not to the torpedoes of the enemy but gunfire. Set on fire, she became a beacon for every Japanese gun close enough to get a shot in. U.S.S. Quincy was next, dealt a lethal blow from a combination of torpedoes and shellfire. She managed to get off nearly two-dozen rounds but only one of these was telling, striking Chokai’s operations room.

Vincennes soon found herself the object of the enemy fleet. She was just to starboard of the burning Quincy when two torpedoes struck her. And then the shells came. “We were heavily hit,” Captain Frederick Riefkohl of the Vincennes reported. “Shells landed all around the bridge. The barrage continued as we turned, then as we swung right with the torpedo hits, an additional one or possibly two, struck at the same time, and all power went off the ship.”

By 0240 it was over. Mikawa ordered a withdrawal. The Chokai had been roughly handled as well as the Tenryu (she would be torpedoed the next day and sunk), but the Imperial Japanese Navy had handed the combined forces of the Royal Australian Navy and the United States Navy a defeat. Mikawa could have pushed his way to the virtually undefended landing fleet; but he chose to disengage. That could be identified as a victory of sorts by the allies. In fact, it gave the marines on the Canal a reprieve, and made all the difference in the world to the future of Guadalcanal.

Writing later of the various actions around Guadalcanal, Samuel Eliot Morrison summed it up quite nicely. “In torpedo tactics and night actions, this series of engagements showed that tactically the Japanese were still a couple of semesters ahead of the United States Navy, but their class standing took a decided drop in the subject of war-plan execution.”

=================================================================================

NB: The above text has been collected / excerpted / edited / mangled / tangled / re-compiled / etc ... from the following online sources :

IJN Long Lance - Type 93 Heavy Torpedo - wikipedia

IJN Long Lance - Type 93 Heavy Torpedo - www.combinedfleet.com article #1

IJN Long Lance - Type 93 Heavy Torpedo - www.combinedfleet.com article #2

IJN Long Lance - Type 93 Heavy Torpedo - www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk

IJN Long Lance - Type 93 Heavy Torpedo - www.military.com/