undefined

undefined

Norsemen - The Viking Voyagers

==========================================================================

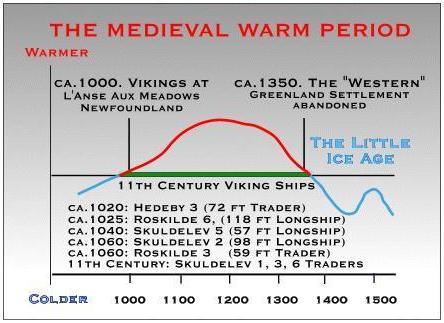

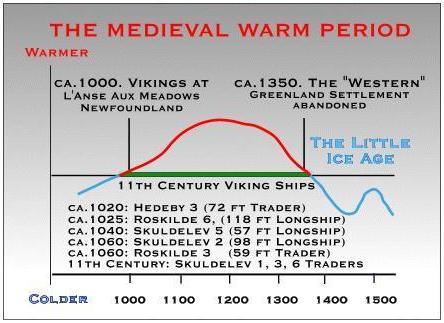

Arguably the greatest achievement of the Vikings was their boat and shipbuilding mastery. The Vikings were not the first people to build ships but they did build the best ships anyone had made up to that time.

The longship is part of the popular image of the Vikings today but there were many different types of boat for different purposes. so far no two boats have been found that are the same.

There are some characteristics that make Viking boats distinctive.

The hull is made up of overlapping planks of wood that are held together with iron rivets. This construction is both strong and flexible, qualities necessary for ocean going vessels.

To maintain this flexibility, the hull of some ships was fixed to the main timber frame with ties rather than nails.

Viking ships were pointed at each end and wide in the middle, this often meant that they could sail in relatively shallow waters.

To date no sail has survived intact but we have much pictorial evidence that they bore a square sail. Modern reconstruction’s prove that this is a fast and manoeuvrable combination and if wind was lacking most ships carried oars, also useful for close handling.

It would appear that ships did not have permanent oar benches so the crew must have sat on sea chests to row the ship. In practice this is quite useful as it gives each crew member a space for personal equipment which can be moved about when needed.

At the right side of the ship near the back is a large paddle tied to the hull for steering. This practice gives us the term still used for the right side of a boat “starboard” from the old words “steor”- rudder or steering paddle + “bord”- ship’s side. For many years the left side was called “larboard” from the words “laden”- to load + “bord” this arises because to prevent the steering paddle from being damaged the boat was landed with the quay on the left so they could be loaded.

Having seen for myself the confusion caused by the similar sound of the words starboard and larboard at sea, it is no surprise to me that “port” replaced “larboard” in the sixteenth century. Interestingly the meaning remained basically the same.

Sea going vessels were often mounted with a dragon or serpents head on the prow. It is important to remember that most people of the Viking age were very superstitious by our standards. The dragon head was simply to frighten away sea monsters and spirits. When approaching land the head could be removed to prevent scaring off the friendly land spirits

This tradition survived for many years and is shown on the Bayeux Tapestry to have be practiced even by supposedly Christian sailors.

Viking longboats were by far the best ships before the age of sail.

Using this superior sea-faring technology the Vikings were world travelers in an age when most men never ventured more than a few miles from the place of their birth. Powered by both a square sail and oars, and usually filled with a war party of Norsemen with their shields arrayed along the sides, these serpent headed shallow draft ships could travel on both rivers and the open sea. Viking warriors traveled far and wide seeking plunder, trade, and a glorious death in battle to assure them a place in Valhalla.

Longboats were built on a long keel and rib design that was covered with planking using an overlapping technique which was called "klinker." Klinker hulls are not solidly nailed, but flexibly riveted with hand made iron rivets through drilled holes. They usually had a single central mast with a large square sail and about eighteen oars. They were strongly built with a high bow and stern, and were the most seaworthy craft of their day. They often traveled in fleets and their ability to arrive and escape by water before military resistance could be organized, coupled with their desire for plunder, made them greatly feared raiders throughout Dark Age Europe.

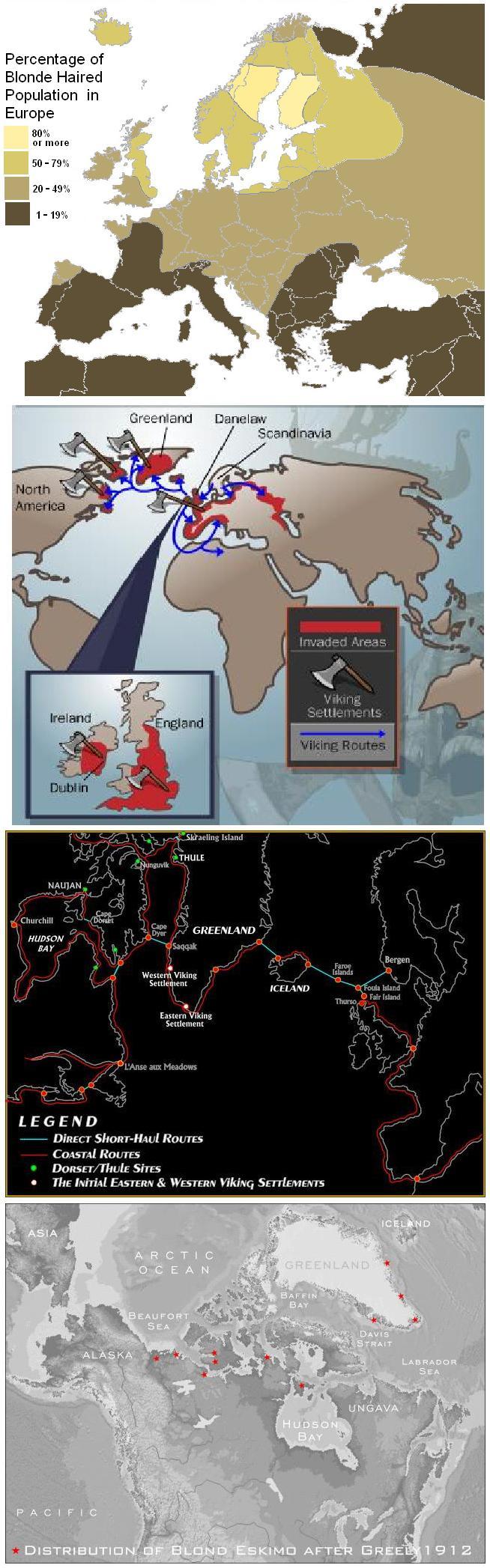

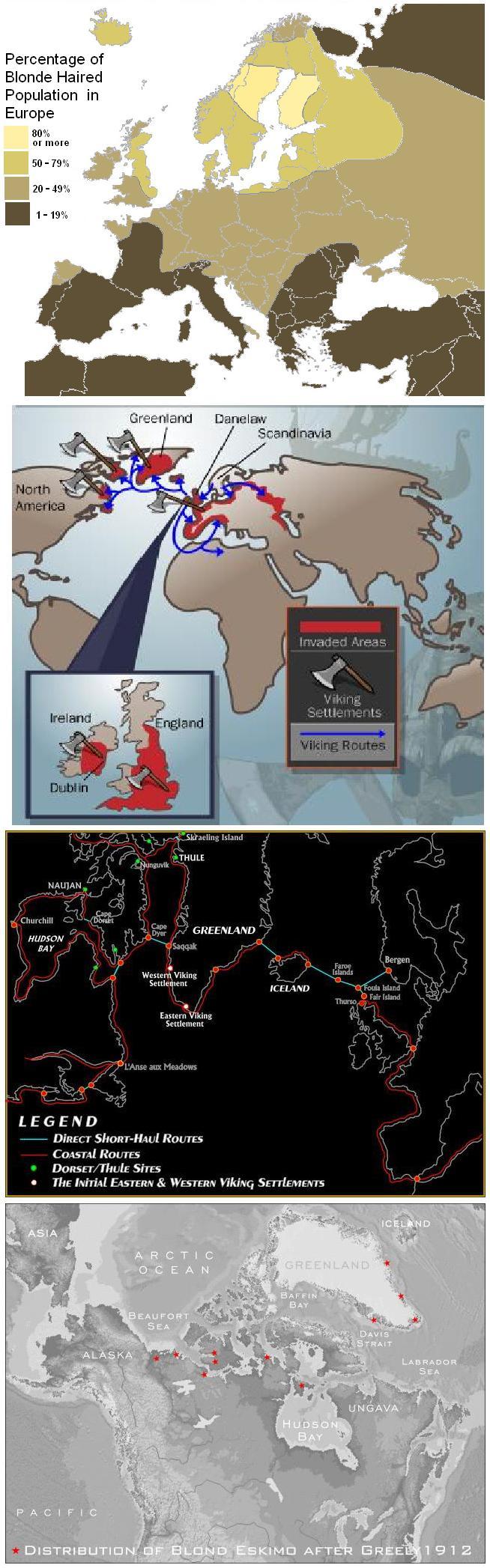

The Viking warlord Eric the Red, and his son Lief Ericson are famous for voyaging west to what would become America. In Europe Catholic Monasteries were a favorite target for raids, as well as river and coastal towns. Some Vikings settled permanently in what became known as Normandy, others attacked and established a Norman presence in Naples. The word Norman, of course, comes from Norsemen or North men. In the east Vikings settled Kiev and Novgorod, and also both sacked and served Byzantium.

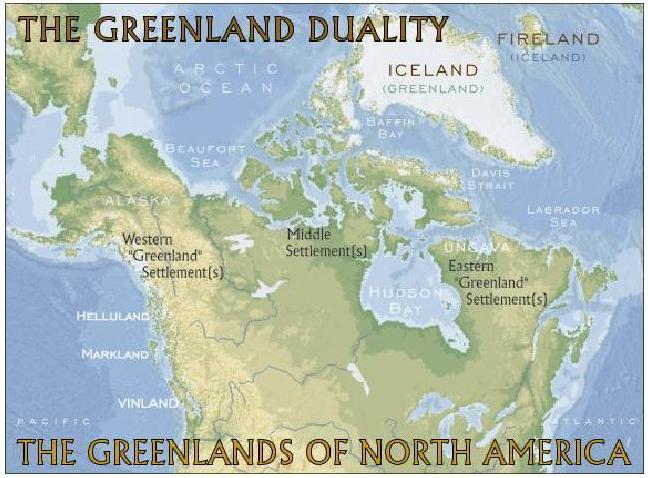

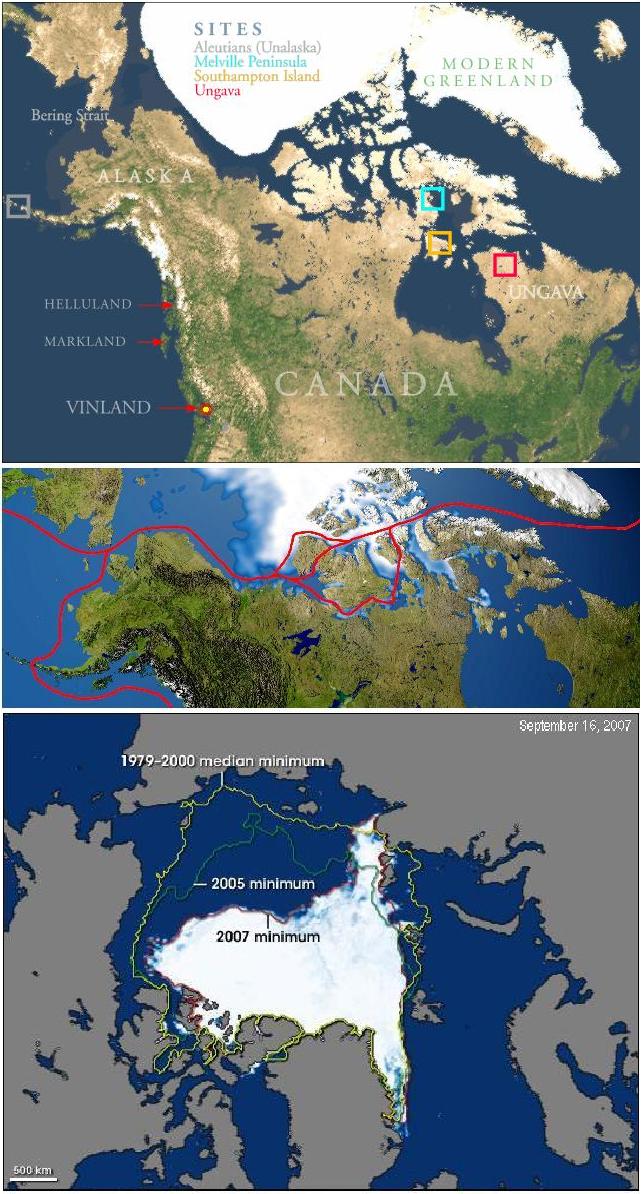

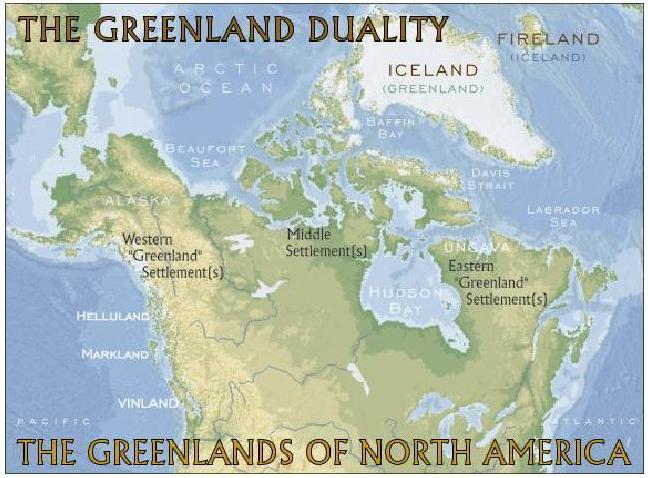

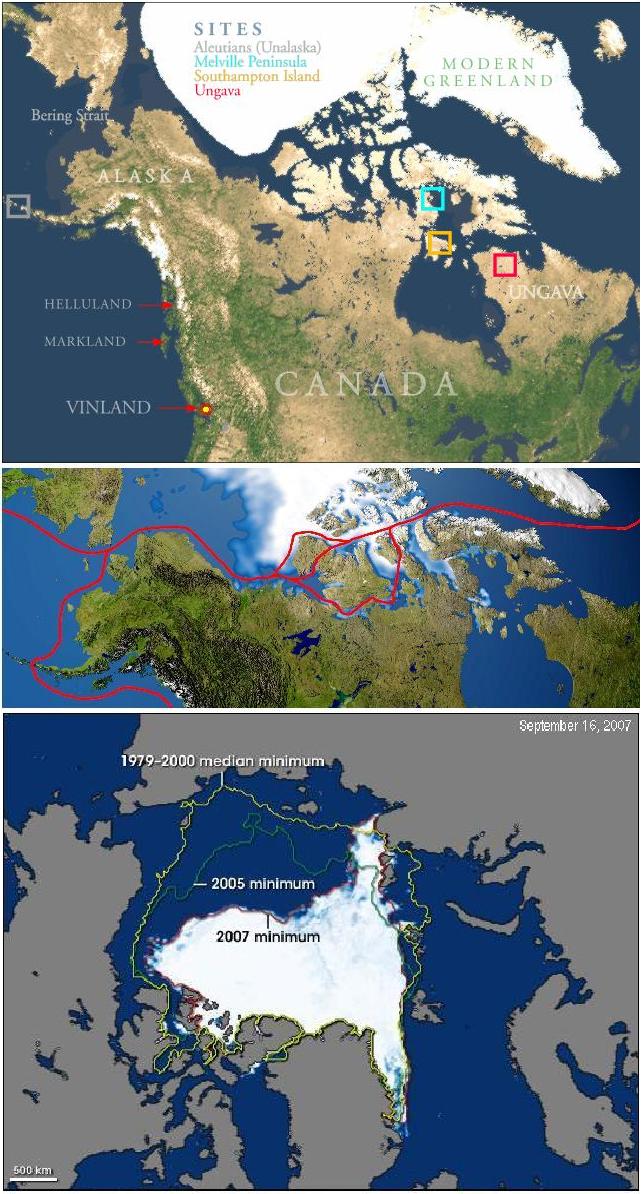

According to old Norse Chronicles Eric and Lief visited Greenland, and Vinland (1001 A.D.). These lands are usually considered by modern scholars to be Greenland as it is seen on maps today, and America. With the icy barrens of Greenland perhaps being given that non-representative name to encourage settlers. Although some claim the northern climates were warmer then. It is also possible that the original Greenland might have been America, but Vinland almost certainly was. Archeologists have found Viking artifacts in Canada (including stone foundations), the Great Lakes (sunken longboat), and New England (Viking trinkets). Thus it is often said that the Vikings, not Columbus discovered America. Some suggest that both the Welsh and the Irish may have also visited America. It is possible that Saint Brendan of Ireland and Prince Maddog of Wales also discovered America, but such ideas, although fascinating, are difficult to prove.

In the east the Vikings sailed as far as Constantinople, probably mostly on rivers through Russia. A group of Norsemen called the Rus settled in Kiev, and modern Russia is said to take its name from them. In 860 Vikings sacked Constantinople which they called Miklagard, or the Great City. The Rus also founded the City of Novgorod far north of Kiev around 866. Vikings were eventually bought off by Byzantine gold, and they went into the service of the Emperor as the Varangian Guard, and served for centuries (Varangian basically means "the sworn").

None of this could have happened without the longboat. If you could get there by water from Scandinavia, the Vikings and their longboats were probably there. However, rounding Africa and making the first permanent settlements in America would be left to the Portuguese and Spanish and the Caravel. The Vikings were probably deterred in Africa by the inhospitable climate and lack of towns to plunder, and in America by their colonizing base being the sparsely populated islands of Greenland and Iceland.

A great knowledge of the ways of the sea was passed down by word of mouth from generation to generation of Vikings. And, perhaps they had some technologies now lost.

The Vikings were great sailors. They could live for months at sea off fish supplemented by scant provisions. They didn’t have compasses or sextants. They did have an oral tradition that passed from father to son a great knowledge of geography, prevailing winds at different places at different times of the year, and also great courage. The later is probably the most important element of Viking navigation, to merely reach your destination with ship, crew, and cargo intact was an outstanding feat. The risks were great, but so were the rewards in wealth and fame for your family. The whole Viking worldview and attitude towards living developed in their bleak cold northern homes made them specially suited for the risks and rewards of sea voyaging.

In addition to a great store of sea knowledge passed down through the generations, and the Vikings also had a few other tricks up their sleeves. One chronicle relates how Floki Vilgerdarson found Iceland by carrying three ravens aboard his longboat. One was released and flew back towards home, a second was released, and perched on the mast refusing to take flight, but the third, when released, pointed the way to Iceland.

In the Vikings home waters of the relatively shallow Baltic Sea sounding (i.e. measuring the depth of the waters) has long been a useful navigation tool for those who know how deep the water is at given places. It is very likely that the Vikings sometimes employed this method.

Stone artifacts have been found bearing scratches that can be used to stay on a certain latitude at different times of the day by reading shadows cast on them. Also knowledge of types of seabirds, seaweed, and other flotsam could inform them of their position relative to land known or unknown, and their ancestral knowledge included a great deal about finding your location by the sun and the stars. However in the far north, the sun is often below the horizon during most of the day, Viking voyages to Iceland, Greenland, and America were almost certainly under such conditions, and often in storms or deep fog. How did they find their way when the sun and stars could not be seen? Several sagas mention a device called a sunstone.

The sunstone is mentioned with reverence and undertones that have made it seem magical and legendary. Many today still believe that it is purely a myth. Others speculate that it was a natural crystal which could refract light, making it possible to see the sun when it is not otherwise visible. Bees and ants use refraction of light to find directions. Did the Vikings do the same? Some modern night compasses work on this principle. Was the sunstone a magical myth like Thor’s hammer, or a simple natural crystal through which the sun could be seen by refraction? Unless one is found in a wreck or byre, we will likely never be sure, but I for one find the theory very plausible.

The facts are indisputable on one thing. The Vikings were the greatest sailors of their time, and their longboats and skills carried them further than any other traveler of the Dark Ages.

So having built your ship, you need to be able to get from place to place, and this is not as easy as it sounds. During the Viking period, there were no readily available maps, in fact there is a lot of dispute as to whether there were any maps at all, and the first known advent of a magnetic compass in north Europe, is in the late twelfth century, so how do you navigate.

The Vikings were experts in judging speed and wind direction, and in knowing the current and when to expect high and low tides. Viking navigational techniques are not well understood, but historians postulate that the Vikings probably had some sort of primitive astrolabe and used the stars to plot their course.

The Danish archaeologist Thorkild Ramskou suggested in 1967 that the "sun-stones" referred to in some sagas might have been natural crystals capable of polarizing skylight. The mineral cordierite occurring in Norway has the local name "Viking's Compass". Its changes in colour would allow determining the sun's position (azimuth) even through an overcast or foggy horizon.

An ingenious navigation method is detailed in "Viking Navigation Using the Sunstone, Polarized Light and the Horizon Board", by Leif K. Karlsen . To derive a course to steer relative to the sun direction, he uses a sun-stone (Solarsteinn) made of Iceland spar (optical calcite or Silfurberg), and a "horizon-board". The author constructed the latter from an Icelandic saga source, and describes an experiment performed to determine its accuracy. Karlsen also discusses why on North Atlantic trips the Vikings might have preferred to navigate by the sun rather than by stars. (Think high latitudes in summer: long days, short to no nights).

A Viking named Stjerner Oddi compiled a chart showing the direction of sunrise and sunset, which enabled navigators to sail longships from place to place with ease. Almgren, an earlier Viking, told of another method: "All the measurements of angles were made with what was called a 'half wheel' (a kind of half sun-diameter which corresponds to about sixteen seconds of arc). This was something that was known to every skipper at that time, or to the long-voyage pilot or kendtmand ('man who knows the way') who sometimes went along on voyages... When the sun was in the sky, it was not, therefore, difficult to find the four points of the compass, and determining latitude did not cause any problems either." (Algrem)

The beauty of Viking navigation was that it was basically so simple that there's not a lot to learn about it.

Latitude Sailing: is a method used by many of the early navigators when their destination was known to be on a particular latitude and east or west of their position. The vessel would be sailed either north or south to the desired latitude, determined by sightings on Polaris (or the stars revolving around Polaris) or the sun, and then sailed along that latitude to the destination. This method was used by early navigators prior to advent of the magnetic compass in the thirteenth century and thereafter used in conjunction with the compass to maintain the desired latitude.

What the Vikings did have was decades of carefully won practical knowledge. The positions of the sun and the stars, and the experiences of previous sailors on that route. How the prevailing winds blew at certain places in certain times of the year. What the reflected loom of a glacier looked like under certain conditions, which birds and seaweed indicated a nearby island. Floki Vilgerdarson, and early Norwegian settler of Iceland, went one better and took three ravens on board with him. A day or so out of the Faeroes, bound towards the recently discovered Iceland, he released the first bird, which headed back to the Faeroes. The second bird was released later and (according to which account you read) either flew up until out of sight, or came back and roosted in the rigging. Some time after that the third raven was released, flew upwards, and then headed straight for Iceland. Floki corrected his course accordingly and made a successful landfall in Iceland.

In terms of instruments: Recent research has revealed that what appeared to be random scratches on the Greenland "bearing dial" actually mark the shadow of the sun at that latitude, enabling you to find the directions at other times other than high noon.

In the late 18th or early 19th century the sailors in the Faeroe Islands were using a wooden disk, marked with concentric circles and fitted with a moveable vertical gnomon (adjustable for the season), floating in a tub, to keep track of their latitude. This may well date from the Viking age. Sailing directions to Greenland (once the colony was well established) were, essentially, "sail west from Bergen at the same latitude until you hit Greenland."

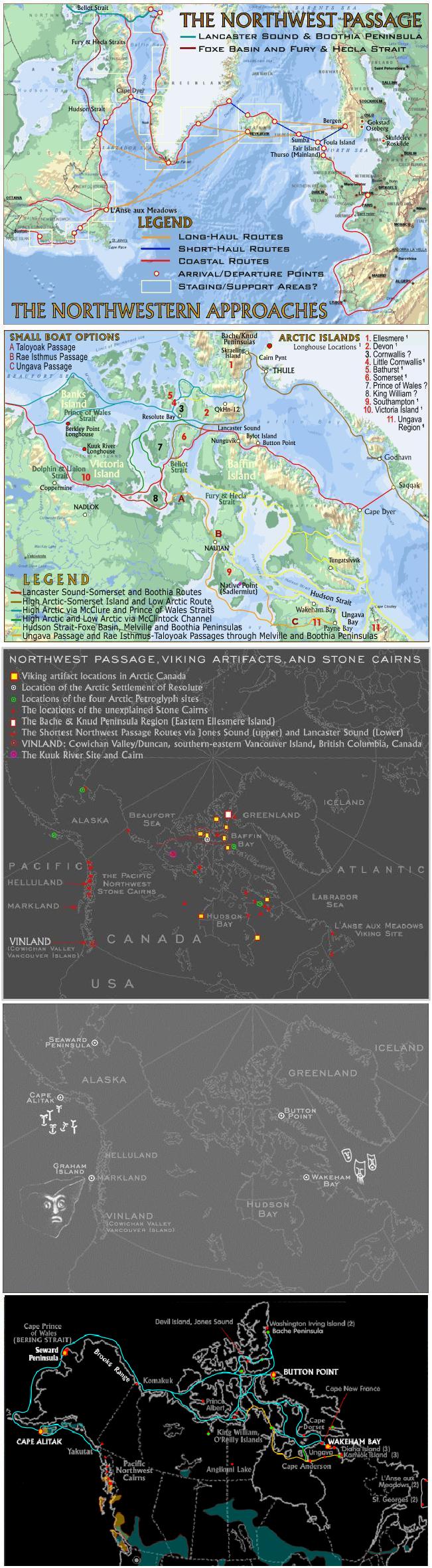

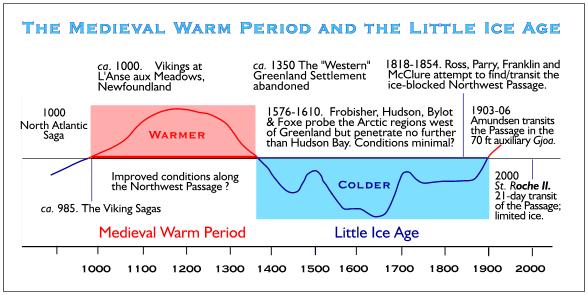

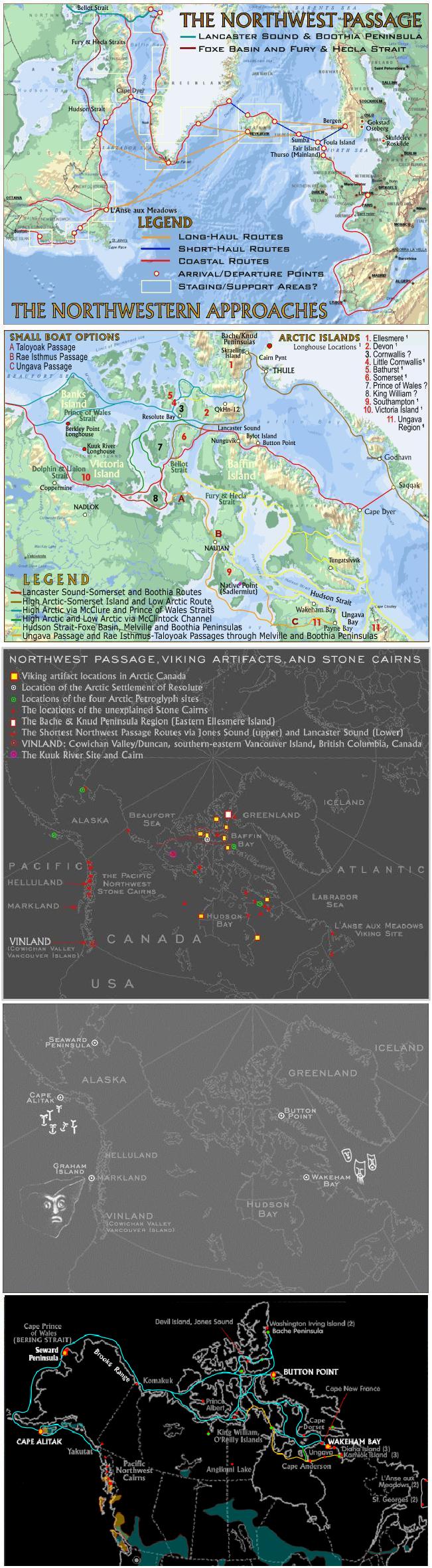

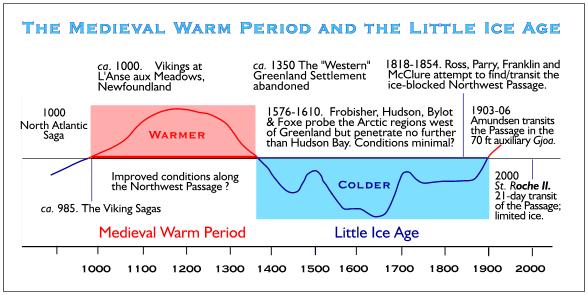

First, there are two largely neglected issues that relate in no small way to the possibility of early transits through the Northwest Passage. Specifically, earlier, around the time of the Viking Sagas and for at least two more centuries (a conservative interval from 1000 - 1200 CE that also happens to include the dates allotted to some of the larger Norse ships) the climate was not only warmer: the sea-level in the Arctic was also quite different from that of the present day.

Sought by explorers for centuries as a possible trade route, the Northwest Passage was first navigated by Roald Amundsen in 1903–1906. The Arctic pack ice prevents regular marine shipping throughout the year, but climate change is reducing the pack ice, and this Arctic shrinkage may eventually make the waterways more navigable.

"In some years now, you can do the Northwest Passage almost in a rowboat"

- - The Vancouver Sun, Jan 30, 2003. - on the subject of global warming

On September 14, 2007, the European Space Agency stated that, based on satellite images, ice loss had opened up the passage "for the first time since records began in 1978". According to the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, the latter part of the 20th century and the start of the 21st had seen marked shrinkage of ice cover. The extreme loss in 2007 rendered the passage "fully navigable". However, the ESA study was based only on analysis of satellite images and could in practice not confirm anything about the actual navigation of the waters of the passage.

Around the time of the Viking sagas and for at least two more centuries (a conservative interval from AD 1000 to 1200 that also happens to include the dates allotted to some of the larger Norse ships), prior to the Little Ice Age some limited regions of the Arctic may have been somewhat warmer than they were in the early 20th century, and were certainly warmer than they were in the depths of the Little Ice Age (see Medieval Warm Period). Also, the sea level in the Arctic was different from that of the present day.

The Migration Period Pessimum (also referred to as Dark Ages Cold Period) was a period of cold climate in the North Atlantic region, lasting from about 450 to about 900 AD. It was followed by the Medieval Warm Period.

This Migration Period Pessimum saw the retreat of agriculture, including pasturing as well as cultivation of crops, leading to reforestation in large areas of central Europe and Scandinavia. This period corresponds to the time following the Decline of the Roman Empire around 480 and the Plague of Justinian (541-542). Climatically this period was one of rapid cooling indicated from tree-ring data as well as sea surface temperatures based on diatom stratigraphy in the Norwegian Sea.

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP) or Medieval Climate Optimum was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region, lasting from about the tenth century to about the fourteenth century. It followed the Migration Period Pessimum or Dark Ages Cold Period.

The MWP was followed by the Little Ice Age. The MWP is often invoked in discussions of global warming. Some refer to the event as the Medieval Climatic Anomaly as this term emphasizes that effects other than temperature were important.

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of cooling occurring after a warmer era known as the Medieval Warm Period or Medieval Climate Optimum. The Little Ice Age brought bitterly cold winters to many parts of the world, but is most thoroughly documented in Europe and North America. It probably brought about the demise of the Norse settlements in Greenland, which had died out by the 1400s. In the mid-17th century, glaciers in the Swiss Alps advanced, gradually engulfing farms and crushing entire villages. The River Thames and the canals and rivers of the Netherlands often froze over during the winter, and people skated and even held frost fairs on the ice. The first Thames frost fair was in 1607; the last in 1814

The severe winters affected human life in ways large and small. The population of Iceland fell by half. Iceland suffered failures of cereal crops and people moved away from a grain-based diet. The Norse colonies in Greenland starved and vanished (by the 15th century) as crops failed and livestock could not be maintained through increasingly-harsh winters. In North America, American Indians formed leagues in response to food shortages.

In 1658, a Swedish army marched across the ice of the Great Belt to Denmark to invade Copenhagen.

In the winter of 1780, sea ice surrounding Iceland extended for miles in every direction, closing that island's harbors to shipping.

Did the Greenland Vikings simply fade away, or was there more to their story and more to the Viking Sagas in addition? It would seem that there was far more. In fact sufficient evidence exists to suggest that the last Vikings triumphed over the Northwest Passage and that the legendary lands of the Viking Sagas - Helluland, Markland and Vinland - are located on the West Coast of North America, not the East. Helluland extending from Etolin Island in Alaska south past the Bella Coola region of British Columbia; the Queen Charlotte Islands more than meeting the basic requirements for Markland with British Columbia's Cowichan Valley at Duncan in the south-east corner of Vancouver Island providing the most logical technical fit for Vinland itself. But this is only part of the story . . .

=================================================================================

NB: The above text has been collected / excerpted / edited / mangled / tangled / re-compiled / etc ... from the following online sources :

Viking Ships - www.lore-and-saga.co.uk

Viking Longboats - article #1

Viking Voyages - article #2

Viking Navigation - article #3

LongShip Navigation - article #4

Viking Navigation - article #5

Viking Navigation - article #6

Last Vikings - The Northwest Passage

Northwest Passage - wikipedia article #1

Dark Ages Cold Period - wikipedia article #2

Medieval Warm Period - wikipedia article #3

Little Ice Age - wikipedia article #4

Other Viking Voyagers ?