Map and Compass Fundamentals

for

Search and Rescue

Part 2

Rick Howard

San Jose Search and Rescue

Taking a Bearing

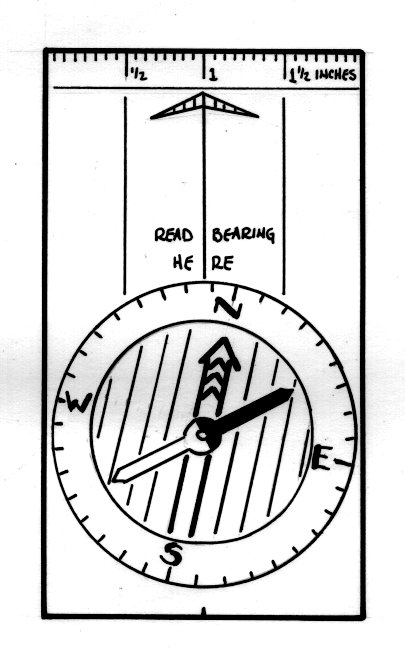

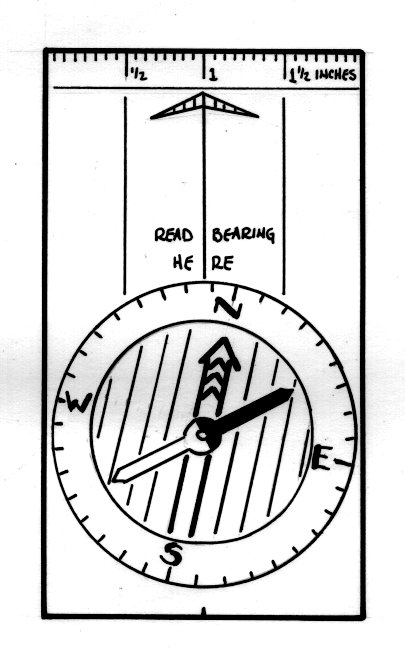

Our compass of choice is either the protractor compass, made of a

compass bezel mounted on a transparent rectangular plate, or the sighting

compass, like the former but with the addition of a mirror on a hinged

compass cover. With the first, one would normally hold the compass out

in front, high enough to sight the desired target over the arrow on the

front of the plexiglas baseplate. Holding the compass steady and level,

and sighting your target, rotate the bezel until you "box the needle" -

that is, place the red north end of the needle in the red box.

You can then read the bearing along the line you are sighting at the

index mark (the compass may even say "READ BEARING HERE" on the baseplate).

(Click here for a full-sized

view of the compass.)

Our compass of choice is either the protractor compass, made of a

compass bezel mounted on a transparent rectangular plate, or the sighting

compass, like the former but with the addition of a mirror on a hinged

compass cover. With the first, one would normally hold the compass out

in front, high enough to sight the desired target over the arrow on the

front of the plexiglas baseplate. Holding the compass steady and level,

and sighting your target, rotate the bezel until you "box the needle" -

that is, place the red north end of the needle in the red box.

You can then read the bearing along the line you are sighting at the

index mark (the compass may even say "READ BEARING HERE" on the baseplate).

(Click here for a full-sized

view of the compass.)

Use of the sighting compass is similar, but with a little more work.

Open the cover about 45° to 60° and hold it up near eye level out in

front of you, sighting the desired object in the "V" notch of the mirror

cover. Adjust the mirror angle for a good view of the compass in the

reflection. Keeping the target in the notch, turn the bezel to box the

needle. Lower the compass and read your bearing at the index mark near

the hinge of the cover.

Suppose you wish to know the bearing of the line from the object to you,

rather from you to the target. This would be the same bearing if you

moved to the target and sighted back along the line you just traveled,

and is called the backsight. The backsight is +/-180° from the

foresight. Many sighting compasses have a mark on the side of the bezel

near you which reads the backsight, that is, the bearing from the target

to you. This feature saves you from having to add or subtract 180° to

determine what your backsight would be - you can read it directly from

the compass.

Sighting a Given Bearing

Now suppose you have been given a bearing that you are supposed to follow

in the field. Just turn the bezel until the index mark ("READ BEARING

HERE") is aligned with the desired bearing. Raise the compass and turn

around until the needle is boxed. Hold the needle boxed and walk out

your designated bearing. Often it's smart to pick out an object at some

distance on the line you have sighted; then you can move ahead to that

point without trying to hold up the compass. Once you get to that

landmark, just raise the compass, take another sighting, pick out

another object on line, and move ahead.

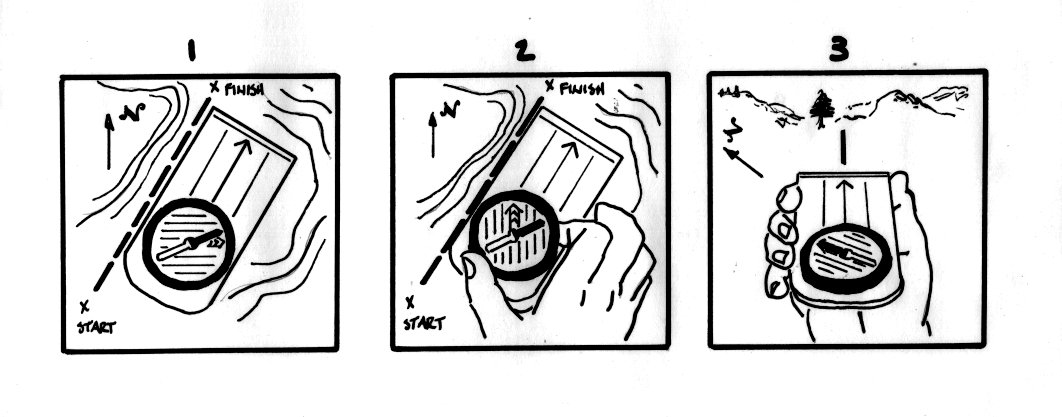

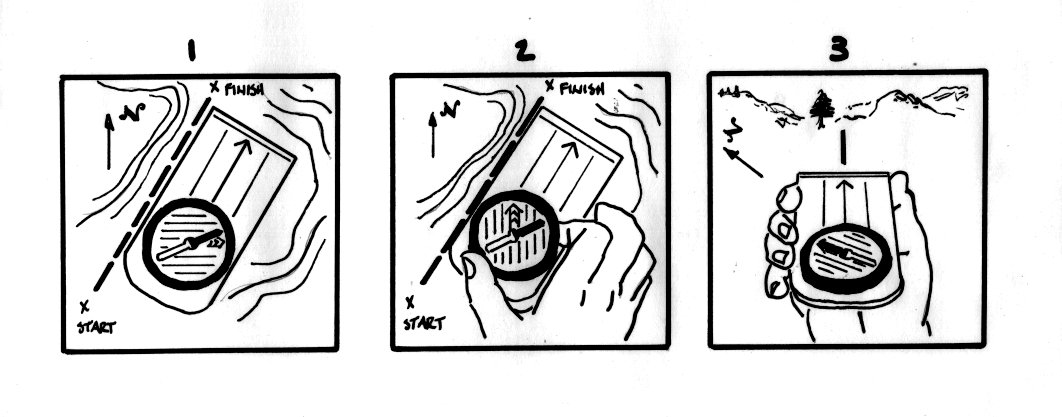

Obtaining the Course from a Map

You are in the field with a map, you know your location, and you have

a destination to get to on the map. First, draw a line between your

position and the destination. Place the side of the baseplate along

this line with the sighting direction of the compass from your position

toward the destination. Turn the bezel until the meridian lines (the

lines parallel to the needle box on your bezel) are lined up with the

meridian lines on the map (ignoring the needle). In other words, the

red north box of the bezel is pointing north on the map. Note that

true north is referenced by setting the meridian lines of the bezel

parallel to the sides of the topographic quadrangle. Now read the

bearing at the index mark ("READ BEARING HERE"). This is your bearing

referenced to true north. Convert to magnetic north, set the correct

magnetic bearing on the compass by moving the bezel to account for

the declination, and follow the bearing in the field as described above.

(Click here for a large

view of the three figures.)

Orienting the Map in the Field

Often you may want to position the map in the field so it matches what

you see. All you need to do is to turn the map with the help of a

compass so the top edge of the map is facing (true) north. Since we're

using the compass, we need to be sure to account for the declination.

There are two common methods.

A) The first approach is to use the magnetic north arrow located in

the margin at the bottom of you map. Turn the bezel so 0° or "N" is

at the index mark. Place the compass on the map with one of the sides

of the baseplate lying along the magnetic north arrow. Then rotate the

map and compass together until the needle is boxed. Doing this, you can

see the magnetic needle of your compass is parallel to the magnetic

north arrow of the map. The map is now oriented.

B) In the second approach, turn the bezel until you have subtracted

the easterly declination from 360°: so you will set about 343° at

the index mark for us here in our part of California. Now place the

compass on the map with one edge of the baseplate lying along one of

the borders of the map (a true north line). Rotate the map and compass

together until the needle is boxed. You should see that the compass

needle (now boxed) is parallel to the magnetic north direction of your map.

Once the map is oriented (and safely secured on the ground!), you can

easily take bearings from the map, because the map is just like what

you see in the field. You can lay the compass along a sight line,

turn the bezel to box the needle, and read the bearing, just like you

would sight on the object itself. In fact, that is what you would do

next. Raise the compass, turn around to box the needle, and you should

be looking at the object in the field, and have a direction to follow.

Likewise, you can take a bearing measured in the field as described

above, set the compass on the map with one side of the baseplate at

your known location, turn the baseplate to box the needle, and follow

the sight (the side of the baseplate) to the object on the map.

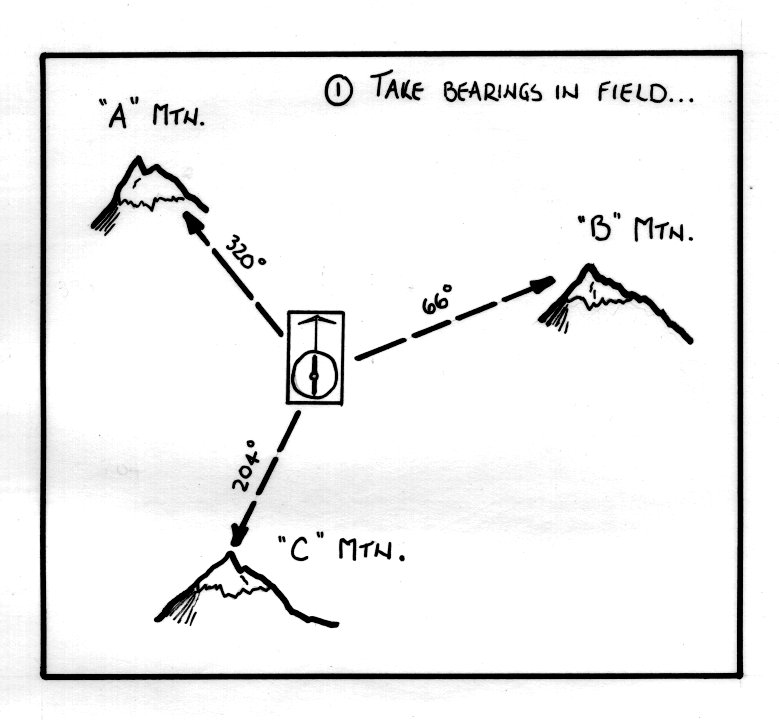

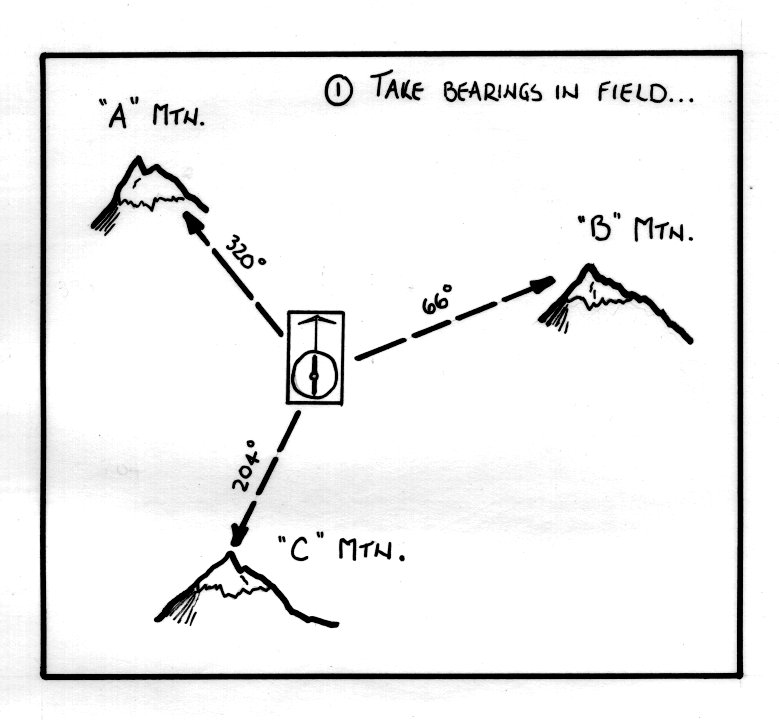

Triangulation

You may find yourself in the field, in view of visible landmarks,

and want to use these objects to help you place your exact location

on the map. To use the intersection of two or more bearings from

known landmarks is commonly called triangulating your position.

Actually, "triangulation" involves determining the three angles of

a triangle (tri-angle: three angles) to locate points in the field,

which requires a surveying transit capable of measuring angles.

What we are really doing with bearings is called "resection" -

plotting the location of our position by taking sights of known points.

Due to its common usage, we'll call it triangulation. The third

method of using field measurements to find your location is trilateration,

which is measuring the lengths of the sides of a triangle to determine

position. GPS units use trilateration - determining the distances

from satellites of known position - to tell you where you are.

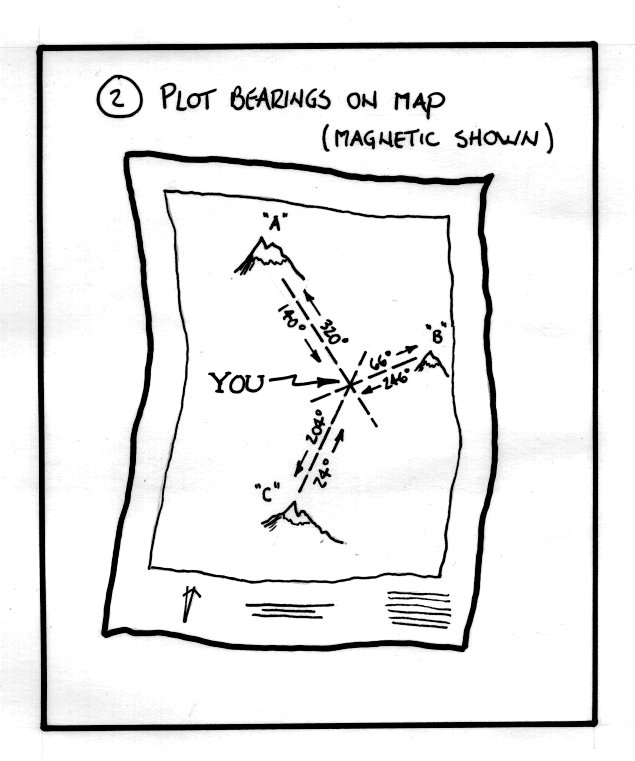

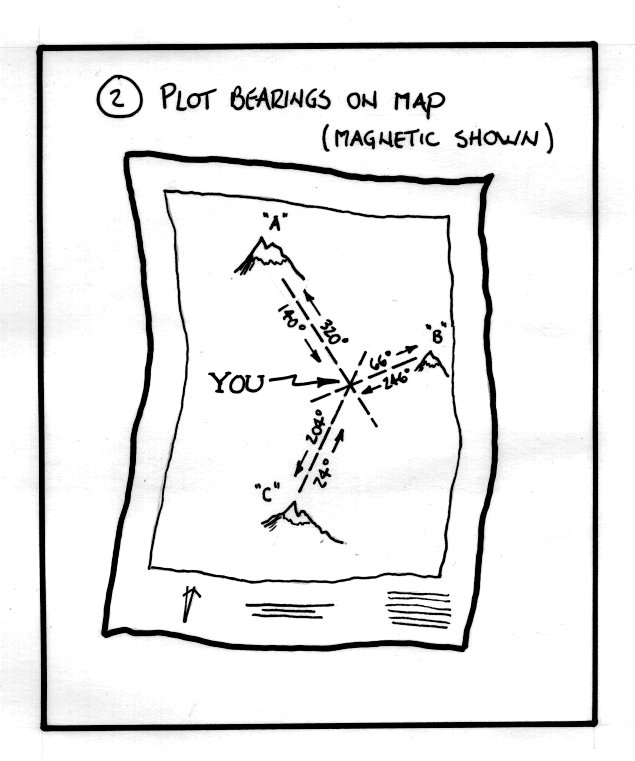

Two landmarks are all you need, but three will give you added accuracy.

Begin by taking a bearing on a landmark and drawing that bearing as

a line through that landmark on your map. If the map is oriented, then

after you take your sight on the object, just drop the compass to your

map and turn the compass to box the needle with one side of the baseplate

touching the object on the map. If the map is not oriented, be careful

to draw the correct bearing on your map. Since the map is reference

to true north, it might be easiest to take the field bearing, convert

to true, and plot the true bearing using your compass as a protractor.

Also note that the actual bearing you want to plot will be from the

landmark to you, so the backsight bearing from the landmark is the one

you want. (Click

here for a large view

of the figure.)

Two landmarks are all you need, but three will give you added accuracy.

Begin by taking a bearing on a landmark and drawing that bearing as

a line through that landmark on your map. If the map is oriented, then

after you take your sight on the object, just drop the compass to your

map and turn the compass to box the needle with one side of the baseplate

touching the object on the map. If the map is not oriented, be careful

to draw the correct bearing on your map. Since the map is reference

to true north, it might be easiest to take the field bearing, convert

to true, and plot the true bearing using your compass as a protractor.

Also note that the actual bearing you want to plot will be from the

landmark to you, so the backsight bearing from the landmark is the one

you want. (Click

here for a large view

of the figure.)

Repeat for a second landmark and for a third, if you have one. All of

the lines drawn should pass through a single point - your position.

If possible, choose landmarks that give about 90° between them for

greatest accuracy. (Click

here for a large view

of the figure.)

Repeat for a second landmark and for a third, if you have one. All of

the lines drawn should pass through a single point - your position.

If possible, choose landmarks that give about 90° between them for

greatest accuracy. (Click

here for a large view

of the figure.)

Navigating Obstacles

We've seen how to extend a line: we can pick out a landmark on our desired

bearing, then get to it any way we can if the way is blocked, then take

another bearing from that landmark when we reach it, and continue on our way.

What if we just come to an obstacle (it could be a large rock, a building,

or a marshy wet area) and we want to detour around it? The best way is to

change course to one side by a certain angle for a certain distance, then

change course by the same angle in the opposite direction for the same

distance. You must estimate the distance, and counting paces is probably

the best way to mark a distance.

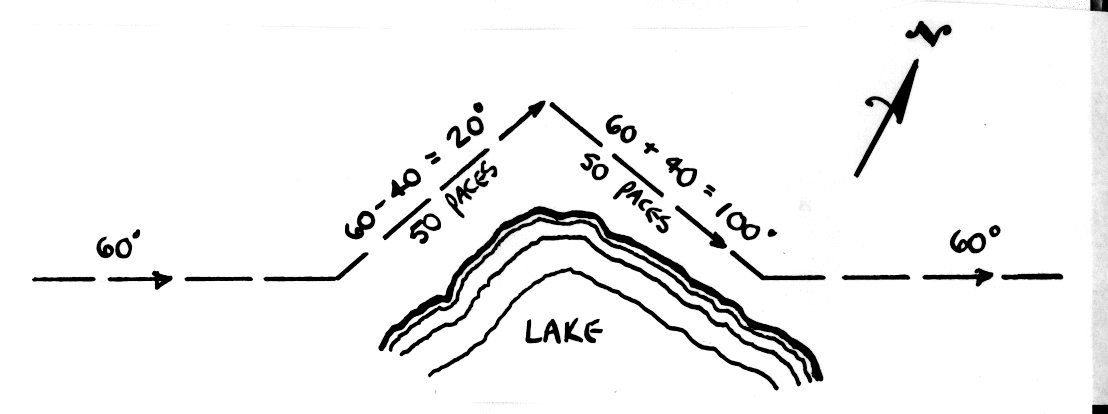

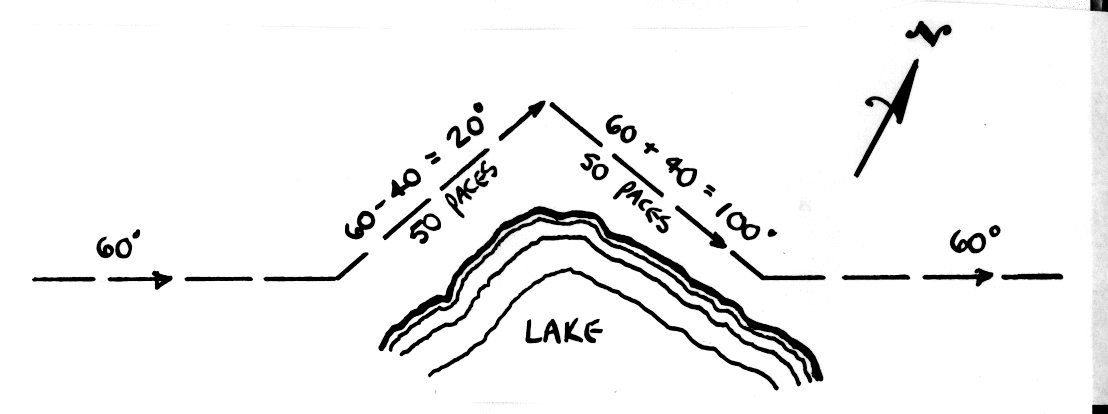

Say you're on a bearing of 60° and find you must detour around a lake.

You could turn 40° to the left, and follow a bearing of 60° - 40° = 20°

for 50 paces. Then turn back 60° + 40° = 100° and follow a bearing of

100° for 50 paces. This detour should bring you back to the original

line. Now set 60° again and continue on your original course. (Click

here for a full-sized view

of the figure.)

Say you're on a bearing of 60° and find you must detour around a lake.

You could turn 40° to the left, and follow a bearing of 60° - 40° = 20°

for 50 paces. Then turn back 60° + 40° = 100° and follow a bearing of

100° for 50 paces. This detour should bring you back to the original

line. Now set 60° again and continue on your original course. (Click

here for a full-sized view

of the figure.)

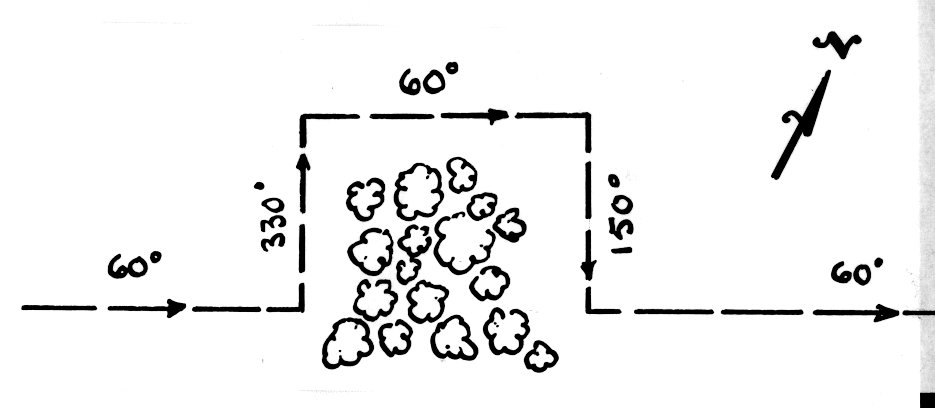

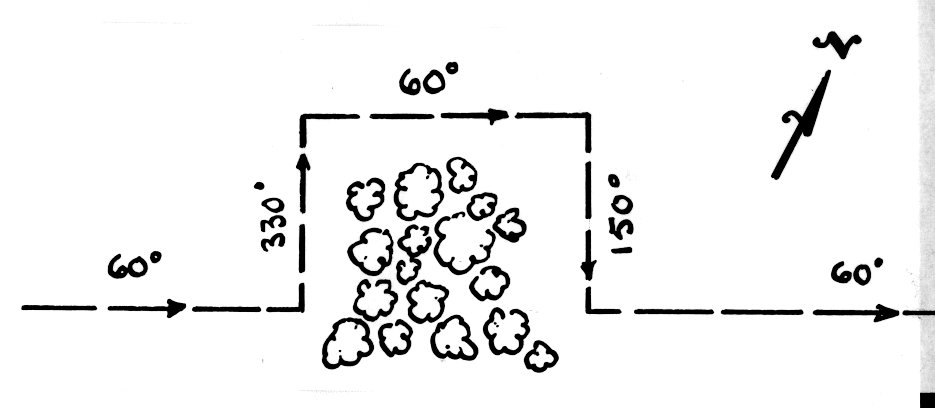

A variation on this method is to make two right-angle course changes.

You might decide to turn 90° to the left to a bearing of 60° - 90° + 360° =

330° and follow this bearing for 30 paces. Then you would follow your

original bearing of 60° for whatever distance it takes to move past the

obstacle. Now turn back to the right to 60° + 90° = 150° for 30 paces to

intersect your original line, from which point you would again set your

original bearing of 60°. This approach is commonly called an offset, and

allows you to easily move past the obstacle whatever distance you need to

before turning back to your original line. (Click

here for a full-sized view

of the figure.)

A variation on this method is to make two right-angle course changes.

You might decide to turn 90° to the left to a bearing of 60° - 90° + 360° =

330° and follow this bearing for 30 paces. Then you would follow your

original bearing of 60° for whatever distance it takes to move past the

obstacle. Now turn back to the right to 60° + 90° = 150° for 30 paces to

intersect your original line, from which point you would again set your

original bearing of 60°. This approach is commonly called an offset, and

allows you to easily move past the obstacle whatever distance you need to

before turning back to your original line. (Click

here for a full-sized view

of the figure.)

You should now be able to read and understand maps, take a bearing, sight a given bearing, obtain a course from a map, orient the map in the field, triangulate to find your location, and navigate around obstacles. All that's left is PRACTICE!

Resources

W.S. Kals, Land Navigation Handbook, Sierra Club Books, San Francisco, 1983.

Bjorn Kjellstrom, Map and Compass, MacMillan, New York, 1994.

US Geological Survey, "Finding Your Way with Map and Compass,"

http://www.usgs.gov/fact-sheets/finding-your-way/finding-your-way.html.

"More About Compasses," REI website,

http://www.rei.com/OUT_THERE/CLINICS/CAMP/backpacking2/comp.html.

Copyright 1998 by Richard M. Howard, San Jose Search and Rescue. Permission granted to reproduce for non-profit,

non-commercial purposes with proper credit given.

Email: seadog@dog.com

Our compass of choice is either the protractor compass, made of a

compass bezel mounted on a transparent rectangular plate, or the sighting

compass, like the former but with the addition of a mirror on a hinged

compass cover. With the first, one would normally hold the compass out

in front, high enough to sight the desired target over the arrow on the

front of the plexiglas baseplate. Holding the compass steady and level,

and sighting your target, rotate the bezel until you "box the needle" -

that is, place the red north end of the needle in the red box.

You can then read the bearing along the line you are sighting at the

index mark (the compass may even say "READ BEARING HERE" on the baseplate).

(Click here for a full-sized

view of the compass.)

Our compass of choice is either the protractor compass, made of a

compass bezel mounted on a transparent rectangular plate, or the sighting

compass, like the former but with the addition of a mirror on a hinged

compass cover. With the first, one would normally hold the compass out

in front, high enough to sight the desired target over the arrow on the

front of the plexiglas baseplate. Holding the compass steady and level,

and sighting your target, rotate the bezel until you "box the needle" -

that is, place the red north end of the needle in the red box.

You can then read the bearing along the line you are sighting at the

index mark (the compass may even say "READ BEARING HERE" on the baseplate).

(Click here for a full-sized

view of the compass.)

Two landmarks are all you need, but three will give you added accuracy.

Begin by taking a bearing on a landmark and drawing that bearing as

a line through that landmark on your map. If the map is oriented, then

after you take your sight on the object, just drop the compass to your

map and turn the compass to box the needle with one side of the baseplate

touching the object on the map. If the map is not oriented, be careful

to draw the correct bearing on your map. Since the map is reference

to true north, it might be easiest to take the field bearing, convert

to true, and plot the true bearing using your compass as a protractor.

Also note that the actual bearing you want to plot will be from the

landmark to you, so the backsight bearing from the landmark is the one

you want. (Click

here for a large view

of the figure.)

Two landmarks are all you need, but three will give you added accuracy.

Begin by taking a bearing on a landmark and drawing that bearing as

a line through that landmark on your map. If the map is oriented, then

after you take your sight on the object, just drop the compass to your

map and turn the compass to box the needle with one side of the baseplate

touching the object on the map. If the map is not oriented, be careful

to draw the correct bearing on your map. Since the map is reference

to true north, it might be easiest to take the field bearing, convert

to true, and plot the true bearing using your compass as a protractor.

Also note that the actual bearing you want to plot will be from the

landmark to you, so the backsight bearing from the landmark is the one

you want. (Click

here for a large view

of the figure.)

Repeat for a second landmark and for a third, if you have one. All of

the lines drawn should pass through a single point - your position.

If possible, choose landmarks that give about 90° between them for

greatest accuracy. (Click

here for a large view

of the figure.)

Repeat for a second landmark and for a third, if you have one. All of

the lines drawn should pass through a single point - your position.

If possible, choose landmarks that give about 90° between them for

greatest accuracy. (Click

here for a large view

of the figure.)

Say you're on a bearing of 60° and find you must detour around a lake.

You could turn 40° to the left, and follow a bearing of 60° - 40° = 20°

for 50 paces. Then turn back 60° + 40° = 100° and follow a bearing of

100° for 50 paces. This detour should bring you back to the original

line. Now set 60° again and continue on your original course. (Click

here for a full-sized view

of the figure.)

Say you're on a bearing of 60° and find you must detour around a lake.

You could turn 40° to the left, and follow a bearing of 60° - 40° = 20°

for 50 paces. Then turn back 60° + 40° = 100° and follow a bearing of

100° for 50 paces. This detour should bring you back to the original

line. Now set 60° again and continue on your original course. (Click

here for a full-sized view

of the figure.)

A variation on this method is to make two right-angle course changes.

You might decide to turn 90° to the left to a bearing of 60° - 90° + 360° =

330° and follow this bearing for 30 paces. Then you would follow your

original bearing of 60° for whatever distance it takes to move past the

obstacle. Now turn back to the right to 60° + 90° = 150° for 30 paces to

intersect your original line, from which point you would again set your

original bearing of 60°. This approach is commonly called an offset, and

allows you to easily move past the obstacle whatever distance you need to

before turning back to your original line. (Click

here for a full-sized view

of the figure.)

A variation on this method is to make two right-angle course changes.

You might decide to turn 90° to the left to a bearing of 60° - 90° + 360° =

330° and follow this bearing for 30 paces. Then you would follow your

original bearing of 60° for whatever distance it takes to move past the

obstacle. Now turn back to the right to 60° + 90° = 150° for 30 paces to

intersect your original line, from which point you would again set your

original bearing of 60°. This approach is commonly called an offset, and

allows you to easily move past the obstacle whatever distance you need to

before turning back to your original line. (Click

here for a full-sized view

of the figure.)