Collecting Vintage Film Cameras

By Lou Padgug

“Kodachrome, they give us those nice bright colors

They give us the greens of summers

Makes you think all the world's a sunny day, oh yeah

I got a Nikon camera, I love to take a photograph

So mama don't take my Kodachrome away”

When Paul Simon wrote the above chorus to the song “Kodachrome”, I wonder if he imagined that Kodachrome film as well as film cameras (also now called analog cameras) would ever become obsolete. And it’s interesting to note that George Eastman’s Kodak company actually invented and produced the first digital camera in 1975. After marketing several different digital camera models through the 1990’s, Kodak decided to sell off the patents and cease production. I guess Kodak didn’t want to hurt its own film business by promoting digital photography but ironically, Kodak’s film business has been drastically affected.

As of this writing, there are still a few film cameras produced. Also, there are still several types of negative and reversal (slide) film produced; mainly 135 (35mm), but also 120, and various sizes of sheet film. Minox has promised to keep producing 11x14mm film for its subminiature cameras although right now, unexpired film is hard to find. Polaroid Originals is a new brand from Polaroid dedicated to analog instant photography in the original, iconic format. It’s the next step in a journey started by The Impossible Project, who kept the format alive since 2008. Launched on September 13th, 2017, the 80th anniversary of the founding of Polaroid, Polaroid Originals makes instant film for Polaroid cameras, and refurbishes vintage cameras so they’re good as new. They also created two new Polaroid instant analog cameras.

As of this writing, there are still a few film cameras produced. Also, there are still several types of negative and reversal (slide) film produced; mainly 135 (35mm), but also 120, and various sizes of sheet film. Minox has promised to keep producing 11x14mm film for its subminiature cameras although right now, unexpired film is hard to find. Polaroid Originals is a new brand from Polaroid dedicated to analog instant photography in the original, iconic format. It’s the next step in a journey started by The Impossible Project, who kept the format alive since 2008. Launched on September 13th, 2017, the 80th anniversary of the founding of Polaroid, Polaroid Originals makes instant film for Polaroid cameras, and refurbishes vintage cameras so they’re good as new. They also created two new Polaroid instant analog cameras.

So why is film still around? Just as some people feel analog “vinyl” records sound better than digital music or CD’s, many photographers believe that film is still superior to digital photography. In several ways that is true but it depends on the size of the film, how either photo is viewed and the quality of the processing and printing of film photos. It takes about 25 megapixels to match 35mm film's practical resolution. It would take about 100 megapixels to match medium format, and about 500 megapixels to match the resolution of 4x5" film. Film has a huge advantage in recording highlights and also records and reproduces a broader range of color. But does all that really matter to the average person who wants a fast and easy way to take photos and share them on the various social media now used? Not really. It does matter to professional photographers who greatly enlarge their photos for display, but I've seen some very large prints from digital photos that rival film prints.

Some of my favorite TV shows are Antiques Roadshow, Pawn Stars and American Pickers. I like to learn about all types of antiques but I’m most interested in vintage mechanical devices such as typewriters, cash registers, sewing machines and phonographs as well as vintage radios. Most of those antiques are fairly large and since I have limited space, I decided to collect vintage film cameras.

Some of my favorite TV shows are Antiques Roadshow, Pawn Stars and American Pickers. I like to learn about all types of antiques but I’m most interested in vintage mechanical devices such as typewriters, cash registers, sewing machines and phonographs as well as vintage radios. Most of those antiques are fairly large and since I have limited space, I decided to collect vintage film cameras.

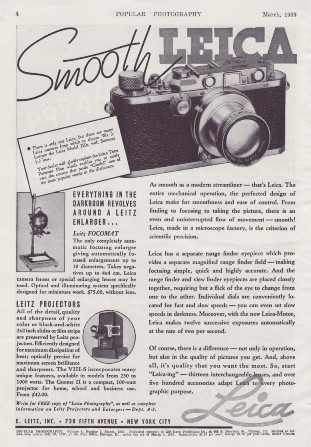

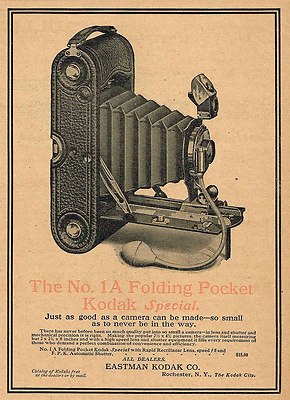

There are several other reasons why I like vintage cameras. First and foremost is I think most of them look really cool, especially some of the older ones made of wood and brass. Several cameras have beautiful Art Deco designs, especially those designed for Kodak by American industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague. I also enjoy learning the history of the different camera companies and appreciate the workmanship that went into producing their cameras. I find the technology used on even the oldest cameras is amazing.

After I started collecting vintage cameras, I found out it is challenging but fun learning how to use them (most cameras in my collection are still functional). Since most of my cameras don’t have built-in exposure meters, I bought a vintage exposure meter and learned how to use it. So far, I have only used a few of cameras but I plan to try all cameras which use available film.

Other than cameras I bought over the years to use, I started my collection several years ago when I replaced two cameras (Minolta-16 MG and Yashica Electro 35) that my father and I originally owned and were subsequently stolen from my house. I found these replacement cameras online and that is where I’ve purchased most of my cameras. I still have my Nikkormat EL with wide angle and zoom lens that I purchased in Germany in 1975 along with over 5,000 slides taken with that camera. I also purchased a Kodak Instamatic 304 for my collection as this was first camera I owned as a kid. My original model had long since disappeared.

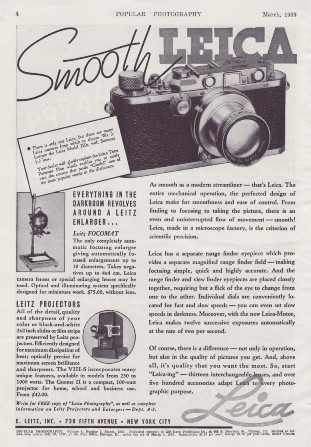

While some people collect one make of camera such as Leica, Zeiss Ikon or Kodak, my collection is more eclectic. I’ve chosen to collect many different makes and formats. It’s amazing how many different formats were designed since the first operational film camera was made in 1816. Unfortunately, film is no longer produced for many of these formats. 116, 126, 616, 620, 828 are all film sizes no longer produced. Actually, some of these can still be found, but only outdated examples. I have purchased several rolls of these films, some produced as far back as the 1940’s but only to display with my cameras. Some photographers in the analog camera movement known as Lomography use expired film as well as old, simple cameras to obtain interesting effects in their photos.

I have a book titled “Camera – A History of Photography From Daguerreotype to Digital” by Todd Gustavson. It features many cameras in the George Eastman collection. After reading the book, I saw much of the actual collection (not all of it is on display at one time) at the George Eastman House/International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York in May 2013.

I have a book titled “Camera – A History of Photography From Daguerreotype to Digital” by Todd Gustavson. It features many cameras in the George Eastman collection. After reading the book, I saw much of the actual collection (not all of it is on display at one time) at the George Eastman House/International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York in May 2013.

I certainly do appreciate my fully automatic, auto-focus zoom digital camera, especially for use on all my travels. Modern digital cameras have so many advantages over film cameras. The biggest advantage of course is with digital cameras, you can shoot hundreds of photos, see them instantly and delete the ones you don’t like without having to pay to have the photos developed. That said, I will always admire the history, technology and style of vintage film cameras.

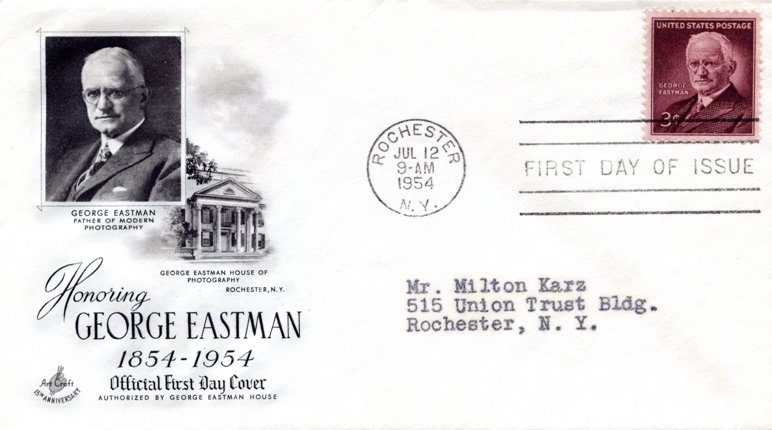

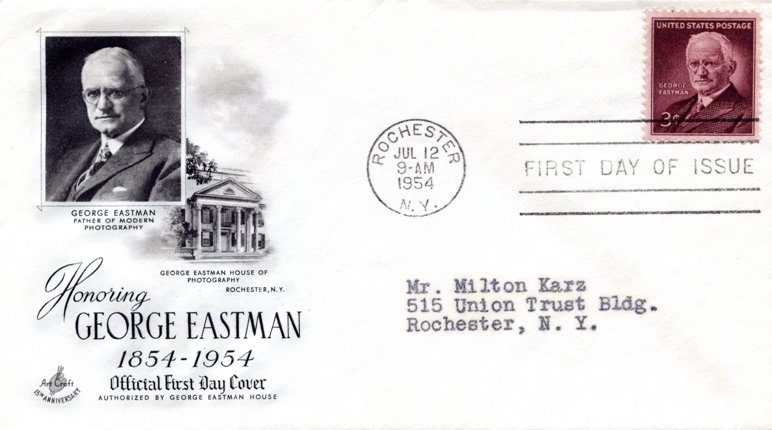

George Eastman

From Wikipedia: George Eastman (July 12, 1854 – March 14, 1932) was an American innovator and entrepreneur who founded the Eastman Kodak Company and popularized the use of roll film, helping to bring photography to the mainstream. Eastman was a major philanthropist donating over $100 million in his lifetime, establishing the Eastman School of Music, and schools of dentistry and medicine at the University of Rochester and in London; contributing to RIT and the construction of MIT's second campus on the Charles River; and donating to Tuskegee and Hampton universities. In addition, he provided funds for clinics in London and other European cities to serve low-income residents. In the last few years of his life Eastman suffered with chronic pain and reduced functionality due to a spine illness. On March 14, 1932 Eastman shot himself in the heart, leaving a note which read, "To my friends: my work is done. Why wait?"

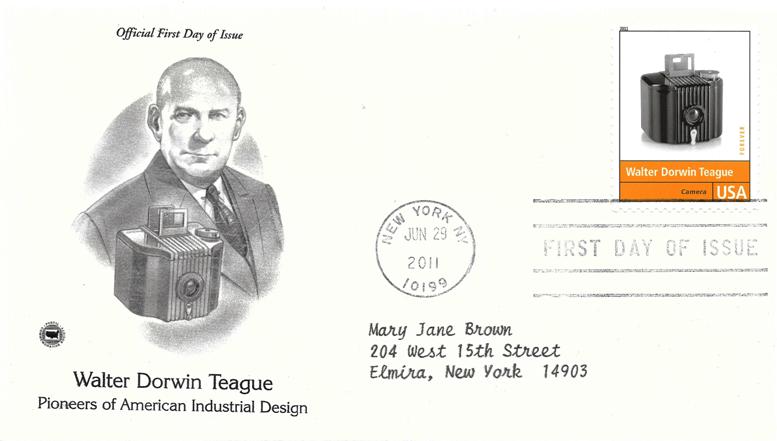

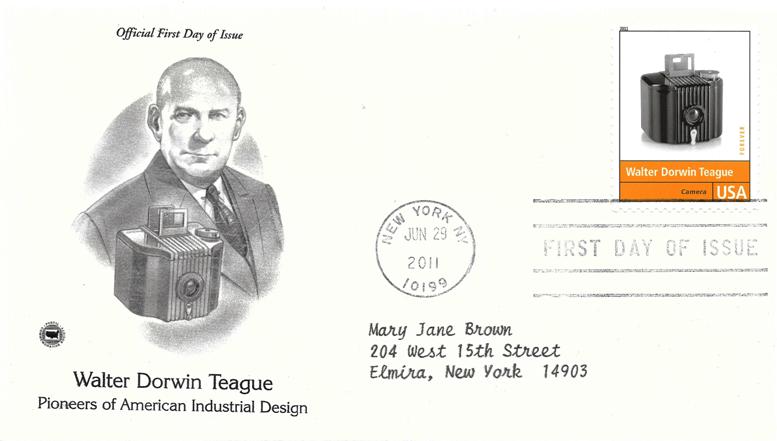

Walter Dorwin Teague and Kodak

From Wikipedia: Walter Dorwin Teague (December 18, 1883 - December 5, 1960) was an American industrial designer, architect, illustrator, graphic designer, writer, and entrepreneur. Often referred to as the “Dean of Industrial Design”, Teague pioneered the establishment of industrial design as a profession in the US, along with Norman Bel Geddes, Raymond Loewy, and Henry Dreyfuss.

Regarded as a classicist and a traditionalist despite a later shift to modern tastes, Teague is recognized as a critical figure in the spread of mid-century modernism in America. He is widely known for his exhibition designs during the 1939-40 New York World's Fair, such as the Ford Building, and his iconic product and package designs, from Eastman Kodak's Bantam Special to the steel-legged Steinway piano. A self-described late starter whose professional acclaim began as he approached age 50, Teague sought to create heirlooms out of mass-produced manufactured objects, and frequently cited beauty as “visible rightness”. In 1926, Teague assembled an industrial design consultancy (now known as Teague), which carries on his legacy today, in name and vision.”

Richard Bach, a curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, had recommended Teague to Adolph Stuber, a top manager of Rochester, New York-based Eastman Kodak, when the company was considering the assistance of an artist to design cameras. With no knowledge of cameras, Teague proposed he work on-site in collaboration with Kodak's engineers. Designing according to engineering necessities, insisted Teague, “ultimately leads to greater beauty and heavier sales.” In Teague's Forbes article, "Modern Design Needs Modern Merchandising” published February 1, 1928, he advises, “The designer who gets results for the manufacturer plans with all departments of a business before he ever lays pencil to drawing board.”

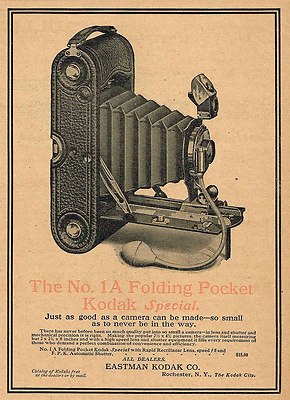

On January 1, 1928, Teague embarked on a design endeavor that culminated in an extensive relationship between him and Kodak — a relationship that would last until Teague's death. He designed a number of well-known Kodak cameras all in the Art Deco style: the No. 1A Gift Kodak (1930), the No. 2A Beau Brownie in five different color schemes (1930), the Baby Brownie (1934), the Bullet (1936), the Bantam Special (1936 - considered a masterpiece of Art Deco styling), and the Brownie Hawkeye (1949).

By redesigning the camera case to match the camera, the two items presented a unity difficult to break during purchase; thus, the sales of carrying cases increased four times over in 1934. Teague's camera designs for Kodak expanded into the design of Kodak's displays, retail spaces, and exhibits. By 1934, the company created an entire styling division, to which Teague's role became advisory.

To see the vintage still and movie cameras, slide and movie projectors, accessories and film in my collection, Click Here.

Back to Main Page

As of this writing, there are still a few film cameras produced. Also, there are still several types of negative and reversal (slide) film produced; mainly 135 (35mm), but also 120, and various sizes of sheet film. Minox has promised to keep producing 11x14mm film for its subminiature cameras although right now, unexpired film is hard to find. Polaroid Originals is a new brand from Polaroid dedicated to analog instant photography in the original, iconic format. It’s the next step in a journey started by The Impossible Project, who kept the format alive since 2008. Launched on September 13th, 2017, the 80th anniversary of the founding of Polaroid, Polaroid Originals makes instant film for Polaroid cameras, and refurbishes vintage cameras so they’re good as new. They also created two new Polaroid instant analog cameras.

As of this writing, there are still a few film cameras produced. Also, there are still several types of negative and reversal (slide) film produced; mainly 135 (35mm), but also 120, and various sizes of sheet film. Minox has promised to keep producing 11x14mm film for its subminiature cameras although right now, unexpired film is hard to find. Polaroid Originals is a new brand from Polaroid dedicated to analog instant photography in the original, iconic format. It’s the next step in a journey started by The Impossible Project, who kept the format alive since 2008. Launched on September 13th, 2017, the 80th anniversary of the founding of Polaroid, Polaroid Originals makes instant film for Polaroid cameras, and refurbishes vintage cameras so they’re good as new. They also created two new Polaroid instant analog cameras.

Some of my favorite TV shows are Antiques Roadshow, Pawn Stars and American Pickers. I like to learn about all types of antiques but I’m most interested in vintage mechanical devices such as typewriters, cash registers, sewing machines and phonographs as well as vintage radios. Most of those antiques are fairly large and since I have limited space, I decided to collect vintage film cameras.

Some of my favorite TV shows are Antiques Roadshow, Pawn Stars and American Pickers. I like to learn about all types of antiques but I’m most interested in vintage mechanical devices such as typewriters, cash registers, sewing machines and phonographs as well as vintage radios. Most of those antiques are fairly large and since I have limited space, I decided to collect vintage film cameras.

I have a book titled “Camera – A History of Photography From Daguerreotype to Digital” by Todd Gustavson. It features many cameras in the George Eastman collection. After reading the book, I saw much of the actual collection (not all of it is on display at one time) at the George Eastman House/International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York in May 2013.

I have a book titled “Camera – A History of Photography From Daguerreotype to Digital” by Todd Gustavson. It features many cameras in the George Eastman collection. After reading the book, I saw much of the actual collection (not all of it is on display at one time) at the George Eastman House/International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York in May 2013.