D-LZ 129 Hindenburg (Deutsches Luftschiff Zeppelin 129) was a large German commercial passenger-carrying rigid airship. It was the lead ship of the Hindenburg class, the longest class of flying machines of any kind and the largest airship by envelope volume. The Hindenburg was named after the late Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934), President of Germany (1925–1934). Designed and built by the Zeppelin Company (Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH) on the shores of the Bodensee (Lake Constance) in Friedrichshafen, the airship flew from March 1936 until destroyed by fire 14 months later on May 6, 1937.

Design and Development:

The Hindenburg had a duralumin structure, incorporating 15 Ferris wheel-like bulkheads along its length, with 16 cotton gas bags fitted between them. The bulkheads were braced to each other by longitudinal girders placed around their circumferences. The airship's skin was of cotton doped with a mixture of reflective materials intended to protect the gas bags within, which were made of goldbeater's skin, from both ultraviolet (which would damage them) and infrared (which might cause them to overheat) radiation. In 1931 the Zeppelin Company purchased 5,000 kg of duralumin salvaged from the wreckage of the October 1930 crash of the British airship R101, which might have been re-cast and used in the construction of the Hindenburg.

The interior furnishings of the Hindenburg were designed by Fritz August Breuhaus, whose design experience included Pullman coaches, ocean liners, and warships of the German Navy. The upper A Deck contained small passenger quarters in the middle flanked by large public rooms: a dining room to port and a lounge and writing room to starboard. Paintings on the dining room walls portrayed the Graf Zeppelin's trips to South America. A stylized world map covered the wall of the lounge. Long slanted windows ran the length of both decks. The passengers were expected to spend most of their time in the public areas, rather than their cramped cabins.

The lower B Deck contained washrooms, a mess hall for the crew, and a smoking lounge. Harold G. Dick, an American representative from the Goodyear Zeppelin Company, recalled "The only entrance to the smoking room, which was pressurized to prevent the admission of any leaking hydrogen, was via the bar, which had a swiveling air lock door, and all departing passengers were scrutinized by the bar steward to make sure they were not carrying out a lighted cigarette or pipe.

Helium was initially selected for the lifting gas because it was the safest to use in airships as it is not flammable. At the time it was extremely expensive, and was only available from natural gas reserves in the United States. Hydrogen, by comparison, could be cheaply produced by any industrialized nation and had more lift. American rigid airships using helium were forced to conserve the gas at all costs and this hampered their operation. Although a hydrogen-filled ship could routinely vent gas as necessary, a helium-filled ship had to resort to dynamic force if it was too light to descend, a measure that took a toll on its structure. Despite a U.S. ban on helium exports, the Germans designed the ship to use the gas in the belief that the ban would be lifted. When the designers learned that the ban was to remain in place, they were forced to re-engineer the Hindenburg to use hydrogen for lift. Despite the danger of using flammable hydrogen, no alternative gases that could provide sufficient lift could be produced in sufficient quantities. One beneficial side effect of employing hydrogen was that more passenger cabins could be added. The Germans' long history of flying hydrogen-filled passenger airships without a single injury or fatality engendered a widely held belief they had mastered the safe use of hydrogen. The Hindenburg's first season performance appeared to demonstrate this.

Propaganda Flights:

The Zeppelin Company chairman, Dr. Hugo Eckener did not make any secret of his dislike of the Nazis and the disastrous events he foresaw. He criticized the regime frequently, and refused to allow the Nazis to use the large hangars at Frankfurt for a rally. His naming of the Hindenburg greatly angered Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels who immediately summoned Eckener to Berlin for a meeting the next day, at which the Nazi minister bluntly stated that he wanted the airship to be renamed the Adolph Hitler. When Eckener refused to do so, Goebbels then decreed that the airship would be referred to in Germany only as "LZ 129" and also warned Eckener that he could easily make the world-famous airshipman a "non-person" in the German media. Although the name Hindenburg lettered in 6-foot-high (1.8 m) red script was finally added to its hull three weeks later, no formal naming ceremony for the airship was ever held.

After a total of six trial flights made over a three-week period from the Zeppelin dockyards where the airship had been built, the Hindenburg was ready for its formal public debut with a 4,100-mile (6,598 km) propaganda flight (Die Deutschlandfahrt) around Germany made jointly with the Graf Zeppelin from March 26 to 29, 1936.

On August 1, 1936, the Hindenburg flew over the Olympic Stadium in Berlin during the opening ceremonies of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games. Shortly before the arrival of Adolf Hitler to declare the Games open, the airship crossed low over the packed stadium while trailing the Olympic flag on a long weighted line suspended from its gondola.

Transatlantic Passenger Operations:

The airship was operated commercially by the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei GmbH (DZR), which had been established by Hermann Göring in March 1935 to increase Nazi influence over zeppelin operations. The DZR was jointly owned by the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin (the airship's builder), the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (German Air Ministry), and Deutsche Lufthansa AG (Germany's national airline), and also operated the Graf Zeppelin during its last two years of commercial service to South America from 1935 to 1937. The Hindenburg and its sister ship, the D-LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II (launched in September 1938), were the only two airships ever purpose-built for regular commercial transatlantic passenger operations, although the latter never entered passenger service before being scrapped in 1940.

The Hindenburg made 17 round trips across the Atlantic Ocean in 1936, its first and only full year of service, with 10 trips to the U.S. and seven to Brazil. In July 1936, the airship also completed a record Atlantic double crossing in five days, 19 hours and 51 minutes. Among the famous passengers who traveled on the airship was German heavyweight boxing champion Max Schmeling, who returned home on the Hindenburg to a hero's welcome after knocking out Joe Louis in New York on June 19, 1936. During the 1936 season the airship flew 191,583 miles (308,323 km), carried 2,798 passengers, and transported 160 tons of freight and mail, a level of success that encouraged the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Company to plan the expansion of its airship fleet and transatlantic services.

The Hindenburg was reportedly so stable that a pen or pencil could be stood on a table without falling. Its launches were so smooth that passengers often missed them, believing that the airship was still on the ground. The cost of a ticket between Germany and Lakehurst was US$400 (about US$6,300 in 2010 dollars), a considerable sum in the Depression era. Hindenburg passengers were generally affluent, including many public figures, entertainers, noted sportsmen, political figures, and leaders of industry.

Over the winter of 1936–37, several changes were made. The greater lift capacity allowed 10 passenger cabins to be added, nine with two beds and one with four beds, increasing the total passenger capacity to 72. In addition, "gutters" were installed to collect rain for use as water ballast.

Another change was the installation of an experimental aircraft hook-on trapeze based on the system similar to the one used on the US Navy Goodyear-Zeppelin built airships USS Akron (ZRS-4) and USS Macon (ZRS-5). This was intended to allow customs officials to be flown out to the Hindenburg to process passengers before landing and to retrieve mail from the ship for early delivery. Experimental hook-ons and takeoffs were attempted on March 11 and April 27, 1937, but were not very successful, owing to turbulence around the area where the hook-up trapeze had been mounted. The loss of the ship ended all prospects of further testing.

The Final Flight:

After making the first South American flight of the 1937 season in late March, the Hindenburg left Frankfurt for Lakehurst, New Jersey on the evening of May 3 on its first scheduled round trip between Europe and the United States that season. Although strong headwinds slowed the crossing, the flight had otherwise proceeded routinely as it approached for a landing three days later.

The Hindenburg's arrival on May 6 was delayed for several hours to avoid a line of thunderstorms passing over Lakehurst, but around 7:00 p.m. the airship was cleared for its final approach to the Naval Air Station, which it made at an altitude of 650 ft. (200 m) with Captain Max Pruss at the helm. However, as ground handlers grabbed hold of a pair of landing lines dropped from the nose of the ship about 7:25 p.m. the Hindenburg suddenly burst into flames and dropped to the ground in just 37 seconds. Of the 36 passengers and 61 crew on board, 13 passengers and 22 crew died, as well as one member of the ground crew, making a total of 36 lives lost in the disaster.

The location of the initial fire, the source of ignition, and the initial source of fuel remain subjects of debate. The cause of the accident has never been determined, although many hypotheses have been proposed. Escaping hydrogen gas will burn after mixing with air. The covering also contained material (such as cellulose nitrate and aluminum flakes) which some experts claim are highly flammable. This, however, is highly controversial and has been rejected by some researchers because the outer skin burns too slowly to account for the rapid flame propagation. The duralumin framework of the Hindenburg was salvaged and shipped back to Germany. There the scrap was recycled and used in the construction of military aircraft for the Luftwaffe, as were the frames of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II when they were scrapped in 1940.

My step-mother actually got to see the inside of the Hindenburg with her father and brother when it was docked in Friedrichshafen near her home. She recalls seeing the dining room tables with white table clothes and flower on them. She also saw it flying over her home.

Below are two envelopes (one with letter still sealed inside) from my collection that were flown on the Hindenburg:

Facts and General Characteristics of the Hindenburg:

Manufacturer: Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH

Registration: D-LZ 129

Constructed: 1931-36

Length: 803.8 feet (245 m)

Diameter: 135.1 feet (41 m)

Volume: 7,062,000 cubic feet (200,000 cubic meters)

Powerplant: four Daimler-Benz DB 602 diesel engines, 1,200 hp each

Maximum Speed: 85 mph (135 km/h)

Crew: 40-61

Passengers: 50-72

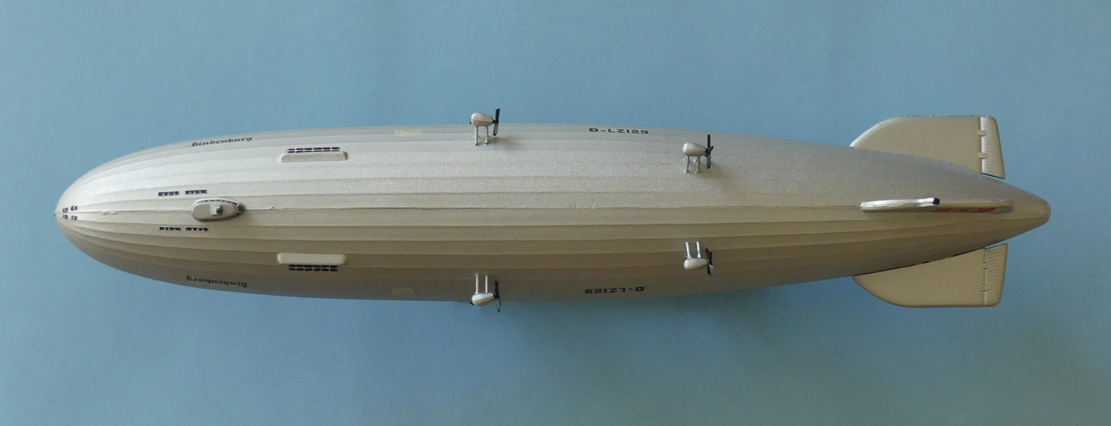

Facts and General Characteristics of the Model (including stand and DC-3):

Manufacturer: AMT Corporation, Troy, Michigan

Scale: 1/520

Length: 18.5”

Diameter: 3.25”

Parts used: 34

Decals: 14

Hours to build and paint: 9.0

Problems/mistakes:

1. This is a very old model kit that has been out of production for about 40 years (I purchased it on an online auction).

2. One half of the hull was warped and putty was needed to fill some gaps.

3. Surprisingly, only four decals split but I was able to repair them.

4. The “Hindenburg” decal should be red, not black.

Shown with Douglas DC-3 for size comparison.

Hindenburg and USS Macon models at the same scale. Hindenburg was less than 20 ft. (6.1m) longer than USS Macon.