The date was May 8, 1956...Alfred E. Neuman makes his first appearance on the cover of MAD magazine. Neuman was indirectly named for Alfred "Pappy" Newman, a noted film composer. He was responsible for the scores of literally hundreds of movies including 'Airport', 'The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance', and 'The Hunchback of Notre Dame', winning nine Academy Awards in the process.

He also composed the

20th Century Fox theme. His brother

Lionel Newman won an Oscar for his

Dr. Doolittle score. And nephew Randy

Newman continued in the family tradition

writing award winning music for such

films as Toy Story. (Randy Newman also

played the singing bush in Three Amigos)

When writers were putting together the

Henry Morgan Radio Show, they named one

of the characters Alfred Newman after

the composer. A few years later some

cartoonists were looking for a name for

their mascot, a character borrowed from

a turn of the century dental

advertisement. Mad Magazine first dubbed

the toothless grinning red head Malvin

Koznowski, but decided instead to steal

a name from the Henry Morgan Radio Show.

The "What Me Worry" kid became known as

Alfred E. Newman.

What year did MAD magazine start?

MAD was first published in 1952 as a comic. It had a cover date of October / November 1952. Starting with issue #24 (July 1955), MAD became a magazine.

What was the original cover price?

The MAD comics had a cover price of 10˘.

The price increased to 25˘ when it

became a magazine (issue #24). Some of

the confusion results from an error in

the Trivial Pursuit game. The question

was: "What was the price of the first

Mad magazine?" and its answer of "Ten

cents". But now we all know the correct

answer.

Who were the original publisher and

editor?

William M. (Bill) Gaines was the

publisher and founder of MAD. Harvey

Kurtzman was the editor. Kurtzman left

MAD after issue #28, July 1956. Albert

B. (Al) Feldstein replaced Kurtzman

starting with issue #29, September 1956.

Where are the MAD offices?

The current location is 1700 Broadway, New York NY. Other locations, staring at the first, included: 225 Lafayette St, 850 Third St, and 485 MADison Ave, all in New York city.

What other countries published versions of MAD?

The following counties published versions of MAD, with the status if the country is still publishing: Argentina, Australia (current), Brazil (current), Canada (Quebec French), Denmark, Finland, France, Germany (current), Great Britain, Israeli, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Puerto Rico, South Africa, Spain, Sweden (current), and Taiwan.

What is the correct spelling of the MAD lexicon words?

Axolotl, borscht, frammistan, farshimmelt, furshlugginer, ganef, halavah, moxie, poiuyt, potrzebie, and veeblefetzer.

How many paperback books were published?

MAD started publishing paperback books with The MAD Reader in December 1954 and ended with Spy vs. Spy The Updated Files #8 by Bob Clarke and Duck Edwing in August 1993. MAD has started reprinting the paperback books again. Between 1954 and 1993, 220 paperbacks books were released. Ninety-four contained previously published material, MAD Stew was credited to Nick Meglin. Bristling MAD (#93, June 1993) was the last reprint book.

Who produced the most books under the

MAD title?

Who produced the most books under the

MAD title?

Not counting the Big Books, Sergio Aragones and Al Jafee each released 16 books. The others: Dave Berg, Frank Jacobs, and Don Martin – 13; Duck Edwing – 12; Dick DeBartolo – 10; Antonio Prohias – 6; Stan Hart and Lou Silverston – 5; Tom Koch, Nick Meglin, and Larry Siegel – 4; Paul Peter Porges – 3; and Max Brandel, Paul Cokers, and John Ficarra – 1.

How many Big Books were published?

There are 10 MAD Big Books. Al Jaffee has 3 under his name and with 1 each: Sergio Aragones, Dave Berg, Dick DeBartolo, Mort Drucker, Frank Jacobs, Don Martin, and Antonio Prohias.

What was the name of the MAD movie?

MAD's answer to National Lampoon's Vacation was "Up The Academy", released in 1980. The movie was so bad Bill Gaines paid to have the MAD logo and references removed from future releases and advertisements. The actor Ron Leibman also demanded that his name not be used in connection with the film.

When did Alfred E. Neuman first appear in MAD?

Alfred E. Neuman's first appearance was on the cover of The MAD Reader paperback book, released December 1954. He next appeared on the cover of MAD #21, March 1955. Alfred E. Neuman became the cornerstone for MAD starting with issue #30, December 1956.

When did Alfred E. Neuman get his name?

Alfred E. Neuman's name first was attached to him in issue #24 as the answer to the Photoquiz, even though none of the multiple-choice answers were Alfred E. Neuman. The name stuck with issue #30, which is the classic Alfred E. Neuman for President drawing by Norman Mingo. What were his other names in MAD?

Alfred E. Neuman had previous names of Melvin Coznowski (#24) and Mel Haney (#25 and 28).

What is the earliest image of Alfred E. Neuman?

This is a tough one because different people can see or not see his likeness in early images. Also many of the early images are not dated. Most collectors will agree that the earliest dated image that is definitely Alfred E. Neuman is from the Atmore's Mince Meat Plum Pudding ad dating from 1895. The ad can be found in the Illustrated London News (the New York City edition).

"I want to talk to the publisher," the boy said.

"I am the publisher," said the person. The boy blinked. The person he was talking to was a shaggy, rumpled hulk, dressed in a faded, pink sport shirt and baggy, unpressed trousers. Most of the bespectacled face was buried behind a hopelessly un-trimmed beard. The rest of the head was enshrouded in a puzzle of hanging hair, styled only by the force of gravity.

"You've got to be kidding," the boy said.

A still from the MAD movie, "Up The Academy"

A still from the MAD movie, "Up The Academy"

No, it was true. William Maxwell Gaines, publisher of MAD, millionaire, gourmet, wine expert, practical joker, King Kong fanatic, zeppelin enthusiast, hater of exercise, and one of the least probable men in the world.

"We all have our many sides," says his sister, Elaine, "but Bill seems to have so many more of them."

Gaines runs MAD on his own terms and would like to run the rest of his life the same way. Shortly after the magazine moved into its present offices at 485 MADison Avenue, he toddled down for a chat with the manager of the building's restaurant, Morgen's East.

"I'm going to be in this building for at least ten years and I'm going to eat in this restaurant, sometimes with guests, at least four times a week, forty to fifty weeks a year," Gaines said. "The only thing I wish is not to wear a tie. If you insist on my wearing a tie, you will lose a lot of business."

"I'm sorry," the manager said, "but we can't let anyone eat here without a tie."

"Okay," Gaines said, and left, crossing the place off his list. Several years later, the restaurant lifted its ban and allowed guests to dine tieless. If Morgen's East thought Gaines would now become a patron, Morgen's East was mistaken. "There is no way I will ever set foot in the place," he says. This is, in some ways, a pity, because Gaines likes comfort and convenience in his life, and the restaurant offers both. But, as he says, "There are some things you can't forgive."

If Gaines had his way, the outdoors would be air-conditioned in summer and heated in winter, and all stairs would be replaced by escalators. For the present, however, he must make do with the imperfect world he has been deposited in.

One night he and I were strolling to a

restaurant.

"Frank, please," he objected.

"What's wrong?" I asked.

"You mustn't walk so fast. We are going

one degree uphill."

Gaines's mind is a nest of compartments, each programmed to make day-to-day living easier. He has special routes for getting about New York and has been known to walk three blocks out of his way in order to avoid a short stretch of uphill climbing. Of course, these are one-way routes. When he leaves the MAD office to lunch at a place, say, five blocks downhill, he will return in a taxi.

One night he and I watched home movies

taken during his boyhood. During a party

sequence, he directed my attention to a

young man jitterbugging. "Look at him,"

Gaines said. "I'll have you know that he

now wears a pacemaker in his heart. Can

there be any doubt why?"

One night he and I watched home movies

taken during his boyhood. During a party

sequence, he directed my attention to a

young man jitterbugging. "Look at him,"

Gaines said. "I'll have you know that he

now wears a pacemaker in his heart. Can

there be any doubt why?"

Gaines has danced twice -— the first time when he took a lesson, the last time at a high school prom when he tried out the step he learned at the lesson. As a boy, he played softball once. He recalls getting one hit, which turned into a home run after the other team Made four successive throwing errors. He might have played a second time, but someone told him he threw "like a girl," which ended any dreams of sandlot glory.

Gaines has skiied once. He gave it up after twenty minutes because of two handicaps: he couldn't bend over to fasten his skis, and when he finally got them on, he would soon fall and lie in the snow, like a beetle on its back, unable to right himself.

Gaines has aquaplaned once. Again there

were physical problems. He required one

hand to hold on to his horn-rimmed

glasses (without them he can't see), and  he required the other hand to keep his

swim trunks from falling, which they did

whenever the boat picked up speed. This

left no remaining hand with which to

hold on to the ropes.

he required the other hand to keep his

swim trunks from falling, which they did

whenever the boat picked up speed. This

left no remaining hand with which to

hold on to the ropes.

But why dwell on one man's inadequacies? There are a number of things that Gaines does well — traveling, eating, wine-tasting, laughing, and, in between all these, publishing MAD.

"My staff and contributors create the magazine," he has said. "What I create is the atmosphere."

During MAD's early years, Gaines employed a stockroom boy named Anthony, a well-behaved, industrious chap, who suffered from only one character flaw — extreme gullibility. One day Gaines revealed that he had a twin brother named Rex.

"Watch out for him, Anthony," Gaines warned. "Rex looks exactly like me except that he has a scar on his cheek and talks loud and mean and nasty. He doesn't have any money, so he steals from other people. If you see him, he'll be wearing my clothes because he stole them from me."

A few days later, Gaines walked out of the office, applied a rubber cement scar to his face, and walked in as Rex. Anthony was appalled to see Rex stride through the office, shouting terrible oaths, bullying the employees, even rifling the petty cash box in Gaines's office. Anthony saw and Anthony believed.

Rex's visits continued. He would demand to see his twin brother, refusing to believe Anthony's explanation that William Gaines was out. Sometimes Rex had a scar on his right cheek, sometimes on his left — Gaines could never remember which he'd used the time before — but Anthony remained a believer. Years passed, and Gaines feared that Anthony was catching on. One morning the phone rang in Gaines's office. "Anthony, it's for you," Gaines shouted. Anthony picked up the phone and, while Gaines looked on, heard Rex's voice, tape-recorded, on the other end: "Anthony, don't say a G**damn word — just listen!" The voice screamed on for thirty seconds, then hung up. Gaines's mother visited the office and was cornered by Anthony.

"Mrs. Gaines, you wouldn't lie to me. Do you really have another son named Rex?" "I'd rather not talk about it," she said.

Anthony was an aspiring playwright. After he left MAD, he wrote a play cal-led The Canary Cage and sent it to Gaines to read. A few weeks later, Anthony phoned to get Gaines's reaction. Rex answered.

"Anthony, I just wantcha to know I'm producing a musical with Rodgers and Hammerstein called The Gilded Canary Cage."

Rex proceeded to describe the plot, which, of course, came from Anthony's script. "That's my play!" Anthony protested. "Yeah," growled Rex, "but can you prove it? I stole it from my brother when he wasn't here, and now it's mine and you can't do anything about it."

Anthony became so hysterical that someone in the office — Gaines never found out who — broke down and revealed the hoax for what it was. Gaines was sorry the gag was blown because he had been planning to end it himself in more appropriate fashion.

"We were going to kill Rex off, stage a funeral, and put up his tombstone in a cemetery, carved for real — 'Rex Gaines, Born 1922 — Died 1959.' It would have been the perfect ending."

More than a decade has passed, and MAD continues to be Gaines's private circus. Financially, the magazine is big business, bringing in a yearly profit in millions, but, unlike other publishing operations, there is a refreshing dearth of pomp and self-importance. This spirit was reflected on the cover of MAD's centennial issue: MAD PROUDLY PRESENTS ITS 100th ISSUE (Big deal!)

The staff works hard to sustain MAD's worthless image. The magazine puts itself down as a cheap rag, containing trash, garbage and other unworthy components. Gaines frets each time inflation forces the magazine to raise its newsstand price. For years MAD flaunted its price as "25˘ – Cheap."

But rising costs forced up the price to "30˘ –Highway Robbery." In 1971, MAD raised its price another nickel. For the next several issues, Gaines tried to placate his readers with these successive front-cover comments: "40˘; Ouch!" "40˘ ; Outrageous!" "40˘; No Laughing Matter" "40˘ ; Relatively Cheap!" "40˘ Cheap (Considering!)" "40˘ Cheap?" and, finally, "40˘ Cheap."

This kind of self-deprecation is unusual for a magazine, but, then, Gaines is not your usual kind of executive. Other publishers may insist their employees punch a time clock. Not Gaines, who lets his people come and go as they please. Other company heads may demand quiet and decorum. Not Gaines, who summons his staff with an interoffice shout and who once gleefully filled the office water cooler with five gallons of white wine and roared with laughter as the day rolled on and he and several of his staff got gloriously swacked.

Gaines's laugh is large and rolling and fills a room, but, then, so does he. "There is no more musical sound in the world than Bill Gaines laughing" says art director John Putnam. "Gaines has an infectious laugh, and if you stand too close to him you can catch a fat flu," says writer Larry Siegel. Even Gaines's ex-wife, Nancy, agrees that he is one of the greatest audiences in the world, although, reflecting on their stormy marriage, "I can't remember ever having done anything that amused him."

Gaines is not the marrying kind, although he has tried it twice. The closest thing in his life to a perfect union occurred when he began publishing MAD. Gaines and MAD, like a boy and his frog, are inseparable.

This personal anecdote from a young babyboomer tells the story of MAD Magazine and the effects of its unique satire better than any biography could. Enjoy!

1967 was the year for me. A blizzard to top all blizzards arrived on my13th birthday, a run for class president (Vote for Harrison, there's no comparison). And the event most bragworthy, a visit to MAD magazine. The trip to New York wasn't exactly meant as a pilgrimage to my shrine- at least not as my mother planned it. But from my perspective, shopping could be done anywhere. Only in Manhattan could an acolyte find the MAD temple, and I was determined to seek it out.

We showed up uninvited on a Saturday afternoon, which wasn't a very good choice of days to come calling, and sure enough, no one answered the door. We knocked and knocked and knocked. As we stood in the hallway waiting for either divine intervention or the onset of surrender, a man from a neighboring office poked his head out and asked if he could help. My mother explained that we had hoped for a tour of MAD's office. He told us he'd give them a call to see if anyone was there. A moment later the door opened--MAD's door.

We were greeted by a very familiar face. In fact, the only face--apart from Alfred E. Neuman himself--that I could possibly have recognized. It was Leonard Brenner. While the names of the entire masthead were as familiar to me as my own family, Mr. Brenner was the only face I had seen before. It had appeared in scores of the ad parodies that adorn MAD's back cover. So when his bearded, bespectacled mug welcomed us in, I couldn't have been more excited.

This

was no office flunky showing us around;

we were being escorted by the one person

who personified the magazine for me.

Although the office disappointed me with

its bland modernity-- I had hoped for

something gothic, cobwebbed, and

labyrinthine--the wonderful clutter of

toys, office supplies, and artwork made

up for it.

Although the office disappointed me with

its bland modernity-- I had hoped for

something gothic, cobwebbed, and

labyrinthine--the wonderful clutter of

toys, office supplies, and artwork made

up for it.

Leonard was extremely kind to me, pressing a MAD badge and one of the MAD paperbacks into my eager hands. And he was glad to pose for a photo, placing a spiked military helmet on my head while my mother focused. He showed us the original color drawing that would be the cover for the upcoming issue. I looked it over carefully and thought deviously how I could parlay this secret information to my advantage back home among the members of my MAD club.

Our visit was over sooner than I wanted,

though my mother's recollection is that

we were given a complete and leisurely

tour. I couldn't bear to leave so soon.

I lingered in front of their bland steel

door for a moment or two just to hold on

to my experience a little longer. The

antiseptic hallway, the linoleum floor,

the shiny drabness--it was all reduced

to insignificance by the proximity of

the MAD logo on the door--the very

emblem of rebellion, frantic energy, and

irony.

on the door--the very

emblem of rebellion, frantic energy, and

irony.

I was going to end this by

reflecting on how the present-day MAD is

not what it used to be. And then I

thought I'd better take a look at the

current issue before I dismissed it so

cavalierly. So I went to the newstand

and had a look--the first close

examination I'd had of it since I

'graduated' to 'The National Lampoon' in

1970. I'd long

ago noticed the absence

of Norman Mingo's classic covers, and in

their place, the wordy, silly covers of

today. They've been enough of a turn-off

to keep me away these past 25 years.

I'd long

ago noticed the absence

of Norman Mingo's classic covers, and in

their place, the wordy, silly covers of

today. They've been enough of a turn-off

to keep me away these past 25 years.

But looking inside now I see

that MAD is

much the same as it's always been. Some

of the artists whose work I had grown up

with are no longer there, but the tone

and the style are little changed.

The easy conclusion to draw would be

that I've changed--and, of course, I

have--but what brought about my apostasy

back in 1970 had more to do with MAD's

influence on my life than a decline in

its quality.

But looking inside now I see

that MAD is

much the same as it's always been. Some

of the artists whose work I had grown up

with are no longer there, but the tone

and the style are little changed.

The easy conclusion to draw would be

that I've changed--and, of course, I

have--but what brought about my apostasy

back in 1970 had more to do with MAD's

influence on my life than a decline in

its quality.

I had become the

converted, and MAD no longer had

anything to teach me. I realize now that

I had become completely and utterly

indoctrinated. The MAD outlook had

become my own. I didn't need the

magazine any longer, because its message

was within me. I had learned to question

all icons, to look skeptically at every

institution of American society; from

Hollywood to Greenwich Village, from

religion to psychoanalysis, from

military intelligence to Madison Avenue.

And I learned to find humor

in unlikely

places. In the lies that politicians

tell. In the conceits of the

'Organization Man' and the beatnik

alike. In the evening news and Sunday's

sermon.

And I learned to find humor

in unlikely

places. In the lies that politicians

tell. In the conceits of the

'Organization Man' and the beatnik

alike. In the evening news and Sunday's

sermon.

So I thank you, MAD, for being such a good influence, and I thank you, Leonard Brenner, for being at work on a Saturday afternoon 28 years ago.

by Tim Madigan

The following article is from the

Secular Humanist Bulletin, Volume 11,

Number 4.

Mad Again. MOE does not necessarily

agree with the ideas in this article but

speech is free where I live,

dudes.

Recently a

subscriber sent me a few

pages from MAD magazine. It had been

many years since I'd seen this

particular publication. During my

grammar school days I had read it (if

you'll pardon the expression)

religiously, but I had long since put

away childish things.

The excerpt in question was entitled

"The Academy for the Radical Religious

Right Course Catalogue," and featured

dead-on caricatures of Pat Robertson,

Phyllis Schlafly, Donald Wildmon, Ralph

Reed and the other usual suspects (MAD

has always been noted for its

outstanding art work). The

article begins: "Funda-Mental

Institution Department: Why do members

of the radical religious right think the

way they do? Are they born like that?

Did they have a bad accident as a child?

A tragic love affair that soured them on

the world? The answer is: none of the

above! You have to be taught to be so

self-righteous and narrow-minded! It

takes years of schooling at a highly

specialized learning institution! And

we've managed to get our grimy little

hands on a brochure for such a

place." The piece then gives

examples of the core curriculum, such as

"Philosophy 101 - The Trap of Thinking:

This introductory course examines the

secular humanism that has infected our

culture as demonstrated by rock music,

PG-13 rated movies and `Gilligan´s

Island´ reruns (which depict several

unmarried men and women alone on a

desert island) . . . All enrollees are

invited to a special seminar in which

the seemingly contradictory theses of

supporting capital punishment while

fighting to protect the lives of the

unborn are empirically

justified." There are also

hilarious cartoons of House Speaker Newt

Gingrich making a surprise appearance at

the Academy, hanging Big Bird in effigy,

and Pat Robertson wielding the bible in

one hand and a wad of money in the

other, "speaking on the theological

connection between donations and

salvation."

This is hard-hitting stuff. I had

forgotten just how explicit and

unrelenting the satire in MAD could be.

But what should one expect from a

magazine that proudly bills itself as

offering "humor in a jugular vein"?

Reading this parody caused me to

reconsider the influence MAD must have

had on my own worldview. While I like to

credit my coming into humanism (and my

falling out of Catholicism) to reading

such sources as James Joyce, Friedrich

Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre, in

hindsight it would appear that my

voracious explorations of MAD during my

parochial school days primed the pump

for my apostasy. In MAD, one

can truly say that nothing is sacred.

This message must have sunk into the

deep recesses of my psyche - even as I

sat through catechism and confirmation

classes, my MAD collection was never far

from my side.

If you are interested in knowing more

about this wacky and wicked publication,

I recommend the book Completely Mad: A

History Of The Comic Book And Magazine

by Maria Reidelbach (Little, Brown and

Company, 1991). Many of the examples

given in the work demonstrate MAD's

irreverent take on religion, such as its

"Religion in America Primer" in issue

#153: "The Priest: This is a Catholic

priest. His church believes in

many things. It believes in miracles.

The priest helps Catholics in time of

need. He helps them solve business

problems, even though he has never been

in business. He helps them solve

marriage problems, even though he has

never been married. He helps them solve

sexual problems, even though he has

never had sex. Now you know why the

Catholic Church believes in miracles!"

But the magazine has doesn't only poke

fun at Catholicism - it skewers all

denominations.

The guiding genius behind MAD was its

founder and long-time publisher, the

late William M. Gaines. I was not

surprised to read in Reidelbach's book

that Gaines was an explicit atheist.

Gaines may well have been one of the

most influential freethinkers of all

time - his magazine has always been in

the forefront of giving the raspberry to

dogmatism wherever it appears. He should

take his rightful place in the pantheon

of humanist heroes, although I'm sure

his first act would be to slip a whoopy

cushion under Voltaire's seat. Gaines'

motto was "don't take anything too

seriously", including satire

itself.

Just to prove that MAD is continuing in

its non-inspirational ways, I picked up

the October 1995 premier issue of Big

Bad Mad: A Collection Of Classic

Out-Of-Print Mad Paperback Insanity Not

Seen In Years! (Big Deal!). It contains

a parody of the film Ghostbusters II,

and in one panel a priest accosts the

Bill Murray character and states "As

clergymen, we're against people

believing in fantastic nonsense like

supernatural superstition", to which

Murray replies: "Yeah. You want people

to believe in everyday stuff like Noah

and the Ark, Jonah and the Whale, and

talking serpents with apples!"

So the next time organized religion and

superstition has you down, don't get

even -- get MAD!

"I first fell in

love with EC comics

around '52. I discovered them just as

MAD comics was starting, so Bill Elder,

who was always the most out there of the

MAD artists, caught my eye immediately."

Said the late Jerry Garcia in one of his

last interviews, "He's part of American

wealth. For me, the fifties were Rock 'n

Roll and EC comics. That was pretty much

it, culturally speaking, that was the

hot stuff."

In the fall before his death, Jerry

Garcia was presented with about thirty

different things that were being

requested of him. One of which was to do

an interview with Will Elder's

biographer. Garcia chose to do two

things, the first of which was to talk

about Will Elder. Elder, according to

Garcia, had a major impact on his youth,

filling him with laughter and enough

gags per-inch to keep him going back and

re-reading the stories to find new ones!

Garcia continues, "I always liked that

thing of overdoing it, and Bill Elder

was, for me, the model of over-doing it!

I thought this guy really knows what

overdoing it is all about.

Al Jaffee, creator of the MAD back cover

fold-in and childhood friend says of

Elder, "Willy is one of the most natural

funny men I have ever known. I think he

is probably at the very top as a funny

cartoonist. He's like an explosion on

the page, he puts in everything that

comes to mind, he just has an instinct

for what is funny in a drawing."

MADMAN'S

SPEECH

French Quebec issue. MAD takes nothing seriously, nothing is too "sacred" to be satirized

French Quebec issue. MAD takes nothing seriously, nothing is too "sacred" to be satirizedTHE MAD

CARTOONISTS: WILL

ELDER

Will Elder

is considered one of the finest,

funniest

and most popular cartoonists on the MAD

staff.

[Look for him at San Diego Comic Con in

July, 2000.]

Will's last public appearance at a comic

convention was in 1976 in NYC. The

guards have finally let Crazy Willy out

to participate in another Comic

Convention. The late legendary Jerry

Garcia of The Grateful Dead was a major

fan and good friend of Will's.

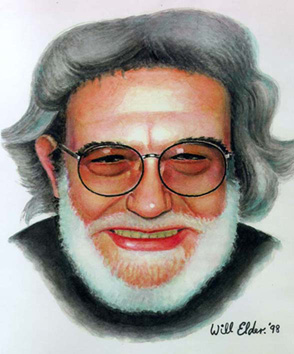

Elder's recent water

color of the late Jerry Garcia

Elder's recent water

color of the late Jerry Garcia Will & Jerry,

Backstage at Madison Square Garden in

October of '94

Will & Jerry,

Backstage at Madison Square Garden in

October of '94