LEADS TO JESSE TUCKER ON CARRIE

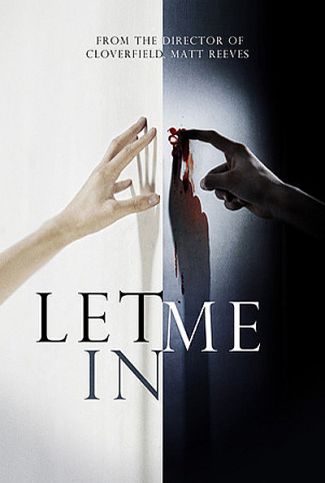

Armond White is not impressed with Matt Reeves' Let Me In, which opened this weekend at U.S. theaters. "This perverted fairy tale about Owen’s guardian vampire degrades the vampire genre simply to exploit adolescent sappiness," White states in his review at the New York Press. White goes on to contrast Reeves' film with "the all-time great adolescent horror movie," Brian De Palma's Carrie. Here are the two concluding paragraphs of White's review:

Armond White is not impressed with Matt Reeves' Let Me In, which opened this weekend at U.S. theaters. "This perverted fairy tale about Owen’s guardian vampire degrades the vampire genre simply to exploit adolescent sappiness," White states in his review at the New York Press. White goes on to contrast Reeves' film with "the all-time great adolescent horror movie," Brian De Palma's Carrie. Here are the two concluding paragraphs of White's review:The 2009 Swedish film Let the Right One In originated this confusion. Its title—borrowed from a 1993 Morrissey song that expressed adolescent longing— sentimentalized moral ambiguity. Abby cannot enter her friend’s home without being invited, requiring his acceptance of evil. Bringing teen anguish to vampire lore (M. Night Shyamalan-style rather than Buffy-style) was lamely nihilistic—and inferior to the vampire romance Twilight that opened the same season. But critics preferred Let the Right One In for its selfpitying view of adolescence. That’s also the sell point of this American remake—add on trite political commentary by setting the story in the nuclear test site Los Alamos, N.M., during the 1980s and frequently cutting to TV broadcasts of President Reagan as a right-wing ghoul warning: “America is good, and if America ever ceases to be good…” So teen anguish gets smashed-up with facile politics, America-hatred and routine Christianity bashing. (Owen’s mother is a grace-saying, Bible-reading drunk whose estranged husband complains about “more of your mother’s religious crap.”) Meanwhile, vampirism—though freaky— gets idealized. But when Abby’s father (Richard Jenkins) mutilates himself after fouling-up a blood-raid/murder-spree and she goes on her own feeding frenzies— including neighborhood lovers and the only cop in town—the gruesome bloodletting lacks the beautiful moral symmetry of the all-time great adolescent horror movie, Brian De Palma’s 1976 teen classic Carrie. Apparently, neither Reeves nor critics remember De Palma’s part-satiric, part-melodramatic demarcation between Carrie’s pathetic need to belong and her tragic acts of revenge.

True to millennial faithlessness, Let Me In rejects Carrie’s complexity, emphasizing both Abby and Owen’s misery. Young scholar Jesse Tucker wrote a brilliant essay describing De Palma’s final twist (where Carrie’s hand grasps her schoolmate’s) as a forgiving gesture toward commiseration. Reeves flips that beautiful motivation in the scene where Owen ignores a reach for help from one of Abby’s victims. It’s an obscene devolution of the genre. Children should not be exposed to this lurid display of helplessness and pessimism—and adult viewers should be wary of the nihilistic indulgence.

JESSE TUCKER ON CARRIE

In November of 2007, Jesse Tucker wrote a review of Carrie in which he presented the intriguing metaphysical interpretation (mentioned by White above) of the final scene in De Palma's film:

A dreamlike sheen hangs over the ending. Sue, the only survivor, sleeps, while in her subconscious she lays flowers on the charcoal pit where Carrie's house used to be. Everyone knows the ending, with Carrie's hand reaching to grab Sue's from another world. It's a shock many people experience come October. But De Palma doesn't use it merely to send us away from the film with a jolt. The gesture is a final, failed attempt to connect. Throughout the film we see the secret pain of abuse, the shock in Chris' face when her boyfriend slaps her, Carrie flinging her advancing mother across the room. Briefly, we see the happy domesticity of Sue's home life. Carrie, beyond the grave, is trying to forge a bond between these girls who exists on the opposite spectrum of life. It fails as Sue wakes up screaming. The other girl is regulated back into the darkness.

(Thanks to John!)

Updated: Friday, October 1, 2010 9:28 PM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post