REFLECTIONS OF LIGHT, TRAIN WINDOWS AS FILM STRIPS, & TWO FANTASTIC SHOTS

The Wayward Cloud posted an interview last week with Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López, in which the pair talk about their audiovisual essay, "De Palma's Vision," which readers will recall had the working title "Count It Out," as it was being prepared for the De Palma retrospective last month at the Metropolis Kino in Hamburg, Germany. ("De Palma's Vision" will be available to watch on MUBI Notebook later this month, sometime after the Cannes Film Festival.) In the interview, they discuss some specifics about "De Palma's Vision," and Martin mentions a series of writings called "The Moves" that he and Álvarez López are doing for Transit. An upcoming edition will focus on a single scene from De Palma, and another will analyze a scene from Samuel Fuller.

In the meantime, here are some excerpts from the interview, in which the pair share some of the things they discovered while working on the audiovisual essay, and in the process, looking very closely at De Palma's films. They also discuss, with a critical eye, their concept of the audiovisual essay. From Wayward Cloud:

Álvarez López: The original idea for the De Palma essay was to talk about things related to vision. It was just a broad concept; we didn’t know what exactly we wanted to say. We began to watch some movies and develop some ideas. These ideas mostly come through repetition and variation: certain scenes and motifs reappear in movie after movie. We began to put them together and then we asked ourselves: What are we trying to say by putting these scenes together? Our answers to this question can become part of the text that we are writing in parallel to our audiovisual exploration – maybe just a paragraph that does not find its way into the final text but that can spark off further ideas. It’s a constant intuitive and intellectual movement back and forth between the text and the films. In this process, we slowly arrive at the best way to arrange scenes and frames which, in the beginning, are only an accumulation of footage.

Martin: We are always trying to find the connection between two pieces of film (or rather, snippets of digital files!). We want to find the connecting line, and we want that connecting line to be clear to the person who eventually experiences the piece. We ask ourselves: in going from this scene to the next, is it perfectly clear what we are connecting? Is it a gesture, is it a situation, is it a composition? The challenge is to make this connection as clear as possible, so that it isn’t just a heterogeneous mess of things. If a certain scene doesn’t fit into this line of connections, it has to go – even if we love it.

Álvarez López: This happened, for instance, with a moment from Mission to Mars – I almost cried because we had to let it go. It’s the moment when they have a hole in the spaceship, but they cannot see where it is. They splash some Dr. Pepper and let it go. The astronauts on the inside see where it gets sucked up, and the one on the outside sees it freezing on the hull of the spaceship, and so he can fill up the hole. In some sense, this scene has to do with the idea of blind vision that we explore in the essay; the fluid can also be described as one of the instruments of vision that pop up in almost all of De Palma’s films. But the fragment of film in which the Dr. Pepper is used would have been very confusing in our essay sequence, because it is filmed in a way that the viewer may not recognise its connection with the theme of vision. It is a telling example, but also it’s too different from all the binoculars, glasses and telescopes that De Palma’s protagonists use as visual aids.

Martin: There are too many things going on in that scene, too many instruments and objects floating around for the viewer to know what to focus on and draw the connecting line to. This is something we reflect upon constantly while working on an audiovisual essay: that every single moment in a film is heterogeneous and has many levels – there are always a million things going on. It’s easy to get lost in the richness of certain moments in a film, but if you start to line up these complex and full moments in an essay, you will start to lose the clearness of connection between details that you want to establish. If you want to make a connection between a camera movement in Welles and one Ophüls, you will have to choose precise moments which won’t get the viewer thinking about the motives of the protagonists.

The Wayward Cloud: Taking your work on De Palma as an example, what were some of the things that you learned about him while working on the essay?

Álvarez López: There were a lot of surprising moments. You see and hear certain scenes so many times that you become aware of a lot of things which you didn’t notice before. You begin to see the details: props in a scene, how a camera movement really works, how complex and well executed the whole mise en scène is. Or, you get to understand the gesture of an actor. For example when we were working on our essay on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Martha and James Foley’s Fear, we already knew beforehand what a great actress Margit Carstensen was. But to again and again see the way in which she turns around when the man (Karlheinz Böhm) tells her that he wants to marry her – well, we really saw for the first time how beautiful and complex this movement is. To constantly repeat and manipulate a scene gives you a different knowledge about it.

Martin: I want to give a really concrete example from the De Palma essay. Everyone who has seen some of his movies knows that there are lot of instruments of vision in them: telescopes, binoculars, cameras. We use this evident idea. But another thing which is not so easy to see are all the reflections of light: in mirrors, knives, shining surfaces. We only saw these instances of reflection and resulting blindness, which pop up again and again and build a complex network of associations in a film like Dressed to Kill, by putting our audiovisual essay together.

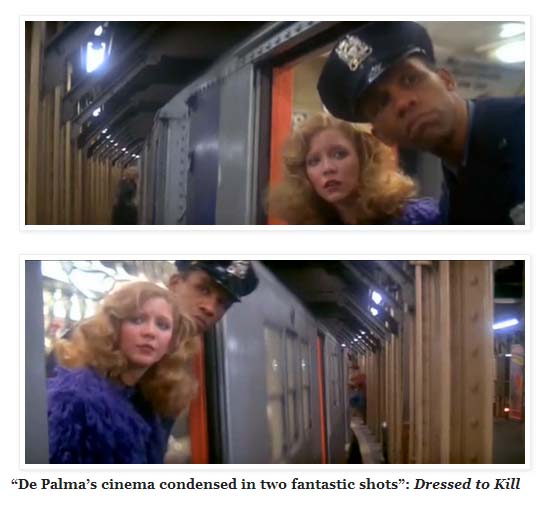

Álvarez López: When I watched Dressed to Kill for the first time, I really liked the scene where Nancy Allen sits in the subway, and you can see the killer hidden behind the door to the next coach. But what I did not remember, and only discovered by seeing it again and developing the theme of blindness, was the scene when Allen and a policeman look right and left along the train and, just when they turn their heads, the killer enters the train out of their sight. Maybe it is because the following scene inside the subway car is so long and powerful, it obliterates this smaller moment. So we bring it back to consciousness.

Martin: That was the scene that the audience most reacted to when we premiered our audiovisual essay in the Metropolis Kino. And rightfully so: it’s De Palma’s cinema condensed in two fantastic shots. But it’s not something you necessarily retain from a single viewing. Another thing which helps you discover things is the use of music. We did that really intensively while working on De Palma – who himself always takes particular care in his selection of music, collaborating with some of the best composers ever like Bernard Herrmann, Pino Donaggio, Ennio Morricone, Giorgio Moroder and Ryuichi Sakamoto. We tried to use the music in a very specific, not wishy-washy way. Just like slow-motion, the unthinking use of music which gets heaped on top of images is one of the things I dislike most in many audiovisual essays.

The Wayward Cloud: You don’t like slow motion?

Martin: To be honest, we used it on the train scene from Carlito’s Way, because we wanted to bring out the idea that train windows are like the frames of a film strip. But generally we dislike the technique, because in audiovisual essays these days, basically everything is put in slow motion, it drives me nuts. I do not know why people do it, maybe they want to be like De Palma, maybe they think it’s poetic. It becomes an all-over, all-purpose thing. I like the Kate Bush music video for “Wuthering Heights” slowed down to 36 minutes – that one pushes the technique someplace extreme and interesting!

Martin: The question of control that a director has over his work is a really interesting one. I think it’s one of the ideals of cinema that the more a director can control his vision, the better. There are certain directors who attempt, even if they may not be always completely successful, to impose his or her will on every detail, to control it, to stylise it. As I said, that’s one ideal in cinema; there are certainly others, but it’s one that I admire very much. When you look at some of the directors we picked – Melville, De Palma, Leos Carax – they are all, I would say, control freaks. In a very interesting book, A Pound of Flesh written by Art Linson, who produced several of De Palma’s movies, he says that De Palma is constantly thinking about how much he can control. He picks his production battles so that he can control what’s in the frame. De Palma also always says that his concentration is on controlling the frame. But, for instance, for directors like Garrel or Rossellini, it’s different. In our essay on Garrel, we did not want to suggest that he controls every single movement; within certain parameters, he just lets his actors go. Rather, we tried to catch a bit of the looseness of this event. That would be an interesting topic for another audiovisual essay: directors who are not so much into control.

Updated: Monday, May 5, 2014 6:07 PM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post