PETER SOBCZYNSKI, SLANT, TRAILERS FROM HELL

Several essays and reviews of Brian De Palma's Sisters were posted this past week, as Criterion released its new director-approved edition on Blu-ray and DVD:

Glenn Erickson, Trailers From Hell

The nigh-perfect score is by Bernard Herrmann, who was probably the biggest item in producer Pressman’s budget. Sisters launches with a gripping title sequence consisting of a progression of macro-photographed fetuses set to Herrman’s crashing horns and screaming Moog synthesizers. One could put that music to pictures of baby kittens, and we’d know they were Kittens from Hell. Herrmann’s prestige keeps the Roe-vs-Wade baby monsters from becoming exploitative: the disturbing opening makes the neutral one-word title instantly sinister. We’re prepared for anything.Out here in Los Angeles, Sisters ‘premiered’ in November 1972’s Los Angeles Film Exposition (FILMEX), and was acquired one month later by American International. I saw parts of it at FILMEX while working as an usher (talk about immediately recognizing music by a specific composer!) and later saw a preview screening in Westwood. Some of the filmmakers were in the lobby afterwards, and I almost walked into a wall when I caught sight of Margot Kidder, who was losing no opportunity for self-promotion.

Variety reviews could usually be relied upon to point out fresh creativity, even in exploitation films. For this show they weren’t as enthusiastic, noting the gory details but minimizing Sisters’ appeal as an ‘okay shocker for the action market.’ The reviewer rather grudgingly noted the filmic references to The Master of Suspense, adding that the ‘Hitchcock-style music’ smooths over the film’s rough edges.

I can’t imagine a 1973 film student not being energized by De Palma’s movie — many of us were in film school because we were inspired by reading about Alfred Hitchcock. As a card-carrying Hitchcock- obsessed film student, I went home and scribbled down a list of Hitchcock allusions, plot points, themes, shots, setups, etc. The only previous movie that I’m aware was consciously constructed of Hitchcock homage material is Riccardo Freda’s L’orribile Segreto del Dr. Hichcock (The Horrible Dr. Hichcock). It wasn’t until much later that I realized Sisters was also a veritable travelogue of witty references to classic horror films that I hadn’t yet seen: Peeping Tom, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, etc.

Here’s the rundown of what I once rudely called ‘Hitchcock Rip-Offs.’

They’re Big Spoilers, so see the film first if you have an analytical memory:Rear Window: A murder seen by an ‘amateur’ is doubted by a police professional. Actions are observed and investigated with binoculars between apartment buildings. Durning’s detective Durning waves, ‘ain’t found nothin’ yet’ from afar.

Psycho: The major prop introduction of the butcher knives. The unexpected knife killing of a likeable character in whom we’ve invested our emotions. The murder clean-up shown in detail. A private detective that disappears from the film mid-case. The revelation that ‘Dominique died on the operating table’ (= ‘Who’s that buried up in Greenlawn Cemetary?’). Various subjective/objective walks, especially the walk leading to the mystery asylum. A trucking-zoom into the pupil of an eye. The psychiatrist blurting out essential exposition for uncomprehending audiences. Kidder’s double identity and the entire Norman Bates personality transference theme. ‘Special guest transferences’: one between psycho killer and psychiatrist, and another between killer and investigator.

Spellbound: The Dali-like dream nightmare (granted, in style it is more akin to a Fellini nightmare).

Suspicion: Philip’s walk with the cake mirrors the walk with the poisoned milk.

The Birds: The pastry clerks (including Olympia Dukakis!) argue behind the counter, just like the hardware proprietor in Bodega Bay. The ‘huh’ ending features an innocuous-sinister exterior landscape with telephone poles.

Lots of Hitch films: Grace’s troublesome Mother, arguing with the cops (calling the police always leads nowhere).

Yes, the ‘borrowed’ situations do stack up. But this is not a lifeless copycat movie. De Palma mounts several inspired set piece sequences that are wholly his own, not merely witty or clever. The Life Magazine newsreel story on the twins provides very effective exposition. But Sisters is best remembered for two killer scenes, the asylum nightmare and the split screen murder.

Enthusiastically received and much discussed was De Palma’s split-screen experiment during and after the opening murder sequence. Hitchcock never tried a split-screen sequence. He had tried many gimmicks in his long career — claustrophobic staging, ultra-long takes, subjective flashbacks, 3-D. But by the time the multiscreen movie at the 1966 World’s Fair made big news, Hitchcock was no longer tinkering with such experimentation. At the time we thought De Palma had been inspired by Richard Fleischer’s 1968 The Boston Strangler, but De Palma’s own Murder à la Mod, released first, uses the technique as well; it also featured actor William Finley.

As was also seen in parts of the Fleischer film, De Palma’s split-screen replaces standard parallel cutting: he simultaneously shows both halves of actions that would normally be intercut one with another. The suspense of the murderers cleaning away traces of the crime while investigators dawdle only a few feet away is very effective. Audiences I saw Sisters with applauded the double-vision synchronous hide ‘n seek game near the elevators.

Grace’s witnessing of the actual murder is equally effective, but brings up a glaring inconsistency, a big Hitchcock no-no cheat. Grace is shown calmly walking to her window perhaps thirty seconds after the actual murder takes place. Seeing a bloody hand writing ‘help’ on a window, she recoils in alarm, indicating that she was unaware of any problem before. And what can she (we) see? She can barely tell that the man is black. The rest of her view, which we see on one half of the split screen, is obstructed by the reflection of a brick wall on the glass. Yet Grace tells the cops she witnessed a murder, knows it was a stabbing, even describes the assailant, who never came anywhere near the window to be identified. It’s a very cute confusion – on first viewing the murder is so shocking and the events so riveting that Savant just took Grace at her word. Maybe it’s another Hitchcock reference — to the ‘lying flashback’ in Stage Fright.

Brian De Palma’s second bravura sequence is the B&W nightmare, an almost perfect horror vision visually unlike anything in Hitchcock. Assembled as a master tracking shot through a fantastic horror scene, it’s stylistically more akin to Federico Fellini. It also has a purpose, to impress on Grace’s mind a traumatic false reality, ‘Manchurian Candidate-style.’ The zoom into the eye of the drugged Grace was probably inspired by Repulsion; it also has the ‘diamond bullet to the brain’ effect of 2001. Inside the mind’s eye is a convincingly warped B&W Dali-scape of elements and characters we’ve seen earlier on, plus a menagerie of grotesques.

Our ability to take the scene literally vanishes as we recognize people that ‘don’t belong’: Grace’s mother and the famous journalist (Barnard Hughes) are among the creepy inhabitants of this asylum. The fisheye nightmare is too theatrical to be one of Polanski’s quietly disturbing dreams in Rosemary’s Baby, and is much more ‘felt’ than the remote creepshows in Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf. Of course, the spectacle is greatly enhanced by Bernard Herrmann sledgehammer music scoring. When Charles Durning is suddenly revealed holding a meatcleaver, the irrational reigns supreme. It’s the director’s doing: nothing in De Palma’s later horrors matches this moment.

Though Brian De Palma had directed several accomplished features before it, Sisters feels in many ways like a debut film. It’s certainly De Palma’s first attempt to marry the edgy satirical textures of his earlier work with a recognizable genre narrative. Or, more bluntly, Sisters is De Palma’s first horror thriller, which is the genre that has allowed him to express himself fully. Like many debut films, Sisters is self-conscious and intellectually guarded, lacking the emotional vibrancy of its creator’s future productions, but it’s also a stunning work of style that erupts into ferocious madness.Sisters opens on what was already then a classically auto-critical kind of De Palma joke. A blind woman, Danielle (Margot Kidder), strolls into a dressing room where a man, Phillip Woode (Lisle Wilson), is changing. Unaware that anyone else is in the room, Danielle begins to disrobe. Until this point, the sequence plays as a perfectly conventional opening for a thriller, or maybe a comedy, until it’s revealed to be part of a Candid Camera-style show within the film called Peeping Toms, with Phillip as the mark. Danielle isn’t blind and works for the show, which follows contestants as they bet on whether Phillip will watch her undress, turn his head, or alert her to his presence. A polite man, Phillip turns his head, causing the contestants to lose points.

Most obviously, this scene functions as one of De Palma’s references to Alfred Hitchcock, acknowledging the voyeuristic functions, and interrogations, of much of the latter’s filmography. And the title of the game show within the film references Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, which was also concerned with the dehumanizing qualities of media. These references are clever, relatively easy to parse, and safe—representing the sort of violations of a viewer’s trust that ironically broker an audience’s greater complicity in the post-Psycho age, as such rug-pulling encourages us to gleefully anticipate the next trick.

Yet De Palma laces all this potentially smug cleverness with an uncomfortable detail that echoes the social satire of the “Be Black, Baby” sequence from Hi Mom!, and that reveals a major element of his own distinctive voice: his scalding humor and distrust of conventional surfaces. Phillip is African-American, and the game show’s audience and contestants are all white. Which is to say that we’re watching a scene in which white people try to lure a black man into sexually harassing a white woman for their own amusement.

Phillip weathers this offense the way people of color have been conditioned to, with a resigned restraint that’s intended to prevent further accosting. De Palma dramatizes the racial savagery of the game show with an off-handedness that’s amusing and disturbing. In case we miss the point, Phillip is given two tickets to a restaurant called The Africa Room for being a good sport, and Danielle is given a set of knives. These prizes epitomize De Palma’s brutal cleverness, as each play a role in Phillip’s destruction.

This racial satire continues to inform Sisters even as the film morphs into a delirious fusion of Psycho, Rear Window, and Rope that retrospectively suggests a test run for Dressed to Kill. Phillip is this film’s Marion Crane, a subjugated person, initially assumed to be the protagonist, who must die so as to satisfy the whims of a white establishment that’s spinning out of control. De Palma plays with our awareness of Hitchcock’s films, deriving suspense not from the pulling of the narrative rug but from the timing of the pulling.

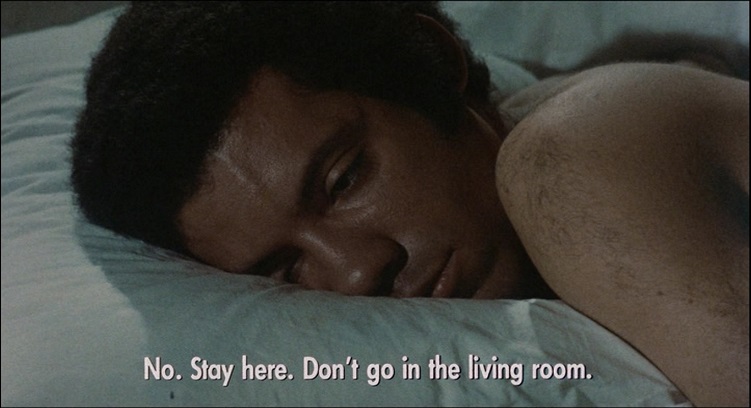

Phillip has sex with Danielle, who’s being stalked by her ex-husband, Emile (William Finley). Phillip overhears Danielle arguing with her twin sister, the pointedly unseen Dominique, who’s enraged that Danielle has a man over at the apartment. Then, Phillip goes to sleep and gets up and buys the sisters a birthday cake—a poignantly thoughtful gesture that seals his doom. Though we empathize with the character, we’re conditioned to become impatient for Phillip’s death so that we may begin to recover from it.

Dying a death as painful and lonely as the one that Marion Crane suffered before him in Psycho, Phillip crawls across the floor of Danielle’s apartment—his blood perversely echoing the color and texture of the icing on the birthday cake—and hands the film’s narrative baton off to Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt). Grace sees Phillip’s hand pressed against Danielle’s window from the neighboring angle of her own apartment and calls the police, whom she’s often criticized in her liberal-minded journalism. And the indifference of the police to Grace’s sensational story of a potential hate crime is visually expressed by one of the greatest split-screen sequences in De Palma’s career: two simultaneous nine-minute shots that contrast Emil’s efforts to conceal the murder with Grace’s efforts to expose it. In an astonishing flourish, we see Grace and Emil just miss each other in a blood-red hallway, suggesting desperate mice in an elaborate labyrinth. And this struggle, to become aware of social atrocity and to expose it, is capped off at the end of Sisters with a galvanizing punchline: Grace, the film’s social crusader, is willed into amnesia.

In prolonged bits and pieces, Sisters shows De Palma to be on the cusp of achieving the mastery that he would display in full by the early 1980s. What the film lacks is the seemingly intuitive sense of emotional escalation that sustains Dressed to Kill and Blow Out, which are so fluid that they almost feel as if they’re composed of a single, breathless shot. Though it climaxes with a mind-fucking in an insane asylum that’s classic in its own right, Sisters is also freighted with tongue-in-cheek exposition that occasionally stops it dead in its tracks, putting unnecessary quotation marks on a grimy, starkly sophisticated fusion of social satire and body horror.

Peter Sobczynski, RogerEbert.com

Even though “Sisters” was De Palma’s first full-out attempt at the suspense genre, one would never be able to discern that thanks to the sheer filmmaking skill that he demonstrates here. After lulling viewers into a state of complacency during the long opening sequence, De Palma begins turning the screws on them with his ability to generate tension thanks to his detailed visual approach. The scene in which Grace’s argument with the cops is juxtaposed with Emil and Danielle trying to clean up Dominique’s mess before anyone else arrives is a virtual master class in filmmaking all by itself in the way that it effortlessly supplies a wealth of information regarding the relationship of Emil and Danielle and the mutual antipathy between Grace and the cops while simultaneously generating equal levels of tension on both fronts. It is a bravura moment that still stands as one of the greatest set pieces in De Palma’s filmography and while nothing else in the film can quite match it, a darker and moodier feel begins to dominate the proceedings—aided in no small part by the spectacularly moody score by the legendary Bernard Herrmann—and the nightmarish final sequence in the asylum, featuring key flashbacks shot in 16mm by De Palma in a manner designed to resemble “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968), is a knockout.One aspect of “Sisters” that makes it a pure product of De Palma is in the usage of voyeurism, a theme that the director would return to time and again throughout his career. In this film, everyone is watching each other, it seems, but from skewed perspectives that prevent them from actually seeing what is right before their eyes. The game show where both Philip and the audience are seeing two different things that are not quite as they seem. Philip sees Emil but can only look at him as a jealous ex-lover of Danielle’s and not as a potential warning sign. Grace witnesses the murder but cannot actually prove anything that she saw and when she does find proof, her inability to watch where she is going ends up destroying it. It is only at the end of the film that people like Grace and Larch are able to see the truth head-on but due to circumstances, neither one is able to communicate the truths that they have seen to anyone, a notion that is perfectly articulated in the haunting shot that brings the story to a close on a deeply ambiguous note.

Even De Palma’s most devoted fans will admit that narrative logic and structure is not always of interest to him and that some of his stories do not exactly stand up to rigorous analysis when all is said and done. Therefore, watching “Sisters” proves to be a bit of a shock because the screenplay that he and Rose have conjured up is actually pretty strong and sound in the way that it provides a sturdy dramatic structure for him to build upon with his weirdo humor and elaborately designed suspense sequences. The opening 20 minutes or so are interesting in the sense that nothing really happens—none of the sex or violence that viewers might be expecting—but the characters of Danielle and Philip are so likable and engaging that it is easy to get lulled into a false sense of complacency that only makes Philip’s murder at the hands of Dominique all the more horrifying. (By employing this kind of slow burn opening, De Palma is utilizing the same approach that he would later deploy in his original version of “Raising Cain” (1992) before restructuring it into the eventual theatrical version.) With all of that going on, he manages to deftly introduce another winning and appealing character in Grace, a contemporary version of the kind of hard-driving crusading female journalist that Glenda Farrell used to play back in the day—the kind who is all about the work and becomes exasperated when her mother (Mary Davenport, Jennifer Salt’s real-life mother) keeps noodging her about when she is going to give up her hobby and finally settle down and get married. As the story progresses, things become increasingly strange and outlandish but De Palma never departs from the logic that he has established early on and indeed, one of the pleasures of watching the film again, once the surprises have been revealed, is to observe just how intricately the elements come together.