INTERVIEW AT "ART OF THE CUT" - SAYS HIS UPCOMING BOOK "IS VERY PERSONAL"

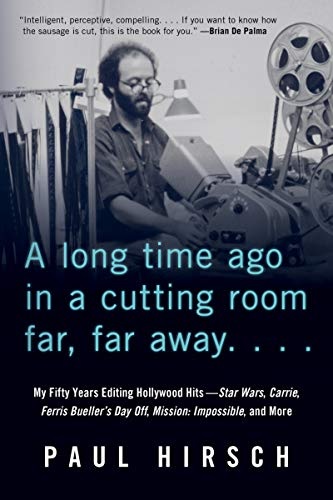

ProVideo Coalition posted an interview the other day with Paul Hirsch, who has edited many of Brian De Palma's films, as well as Star Wars, Ray, and many, many others. Hirsch has a book coming out November 5th, titled A Long Time Ago In A Cutting Room Far Far Away, and he tells Steve Hullfish (who writes the site's "Art Of The Cut" column) that some of the stories he shares in this interview are in the book. "It’s my experiences in the business," Hirsch tells Hullfish, "not a how-to book. The story of my career and how I got started and how things led to where they did. And the pictures I worked on and the fabulously interesting people that I collaborated with and the set of problems that we had to solve and how we did, like swapping out the wide shot of the house in Obsession with the shot of Cliff sleeping which allowed it to get sold. My book is very personal. It’s my experience over my 50 years of editing."

ProVideo Coalition posted an interview the other day with Paul Hirsch, who has edited many of Brian De Palma's films, as well as Star Wars, Ray, and many, many others. Hirsch has a book coming out November 5th, titled A Long Time Ago In A Cutting Room Far Far Away, and he tells Steve Hullfish (who writes the site's "Art Of The Cut" column) that some of the stories he shares in this interview are in the book. "It’s my experiences in the business," Hirsch tells Hullfish, "not a how-to book. The story of my career and how I got started and how things led to where they did. And the pictures I worked on and the fabulously interesting people that I collaborated with and the set of problems that we had to solve and how we did, like swapping out the wide shot of the house in Obsession with the shot of Cliff sleeping which allowed it to get sold. My book is very personal. It’s my experience over my 50 years of editing."Hirsch had asked Hullfish to watch Obsession as preparation for the interview, and that film kicks things off in the following excerpt:

HULLFISH: I watched Obsession — which you had suggested — a lovely movie and then today I watched Mission: Impossible. Same editor, same director – but two very different films.HIRSCH: Well, they were made 20 years apart, and completely different genres.

HULLFISH: Looking at the year of release, was Mission: Impossible your first on Avid or had you done one or two before that?

HIRSCH: Mission: Impossible was the first picture I did using computers. The early 90s was when the big changeover happened, and it was on Lightworks, not Avid.

HULLFISH: Watching dailies is really interesting to me, and since you obviously have come from a place of watching dailies on film could you talk to me a little bit about the difference between watching dailies from the film days to the NLE days?

HIRSCH: It used to be that dailies were shown in a theater every day. The DP would be there, the director, a producer usually, and sometimes — depending on the scene — you might have the costume people and makeup people come to see what their work looked like on screen.

There’s something about the meeting of all those minds in one place in one room at one time that helps solve problems. You can discuss things. “What are we doing tomorrow about this?” and so forth. Now dailies are distributed online. They’re streaming and everybody looks at it individually and at their own pace and so I guess it’s more convenient for everyone else. It’s a phenomenon happening all over, people working in silos.

I feel fortunate to have had my career at a point in the development of the business that was more respectful of the contributions that the various crafts people were bringing to the process. Happiness for me is always proportional to the amount of discretion and autonomy that I have.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I was thinking about when I was watching Obsession was how little coverage there must have been on some of those scenes and the number of takes. The pace is very deliberate. The shots are beautiful. Looking at dailies in that era was a very different thing — like you said — just because of the amount of dailies.

HIRSCH: It was expensive to develop and print. So there was a limit as to how many takes Brian (director, Brian De Palma) was allowed. He could make an exception, but usually not. And he doesn’t cover. He has a very particular idea of the action and the choreography of the camera and how they relate and the blocking the camera and it doesn’t allow for coverage. It’s a shot designed to be in a particular place. I found, working with Brian, I could look at his dailies and know what he had in mind, just from the design of the dailies. And he liked working with me because when he looked at what I’d edited, he’d say, “Yeah that’s what I wanted.” So I wasn’t micromanaged but I still was able to deliver what he wanted.

HULLFISH: And that’s because the intent — when you’re watching the dailies — there were shots that when you watched them on the screen — at least as an editor — I thought that shot at that moment was probably the only thing that you ever considered because Brian shot them in a very specific way and the camera movement revealed things and you probably thought, “Why would I ever break that up with coverage?”

HIRSCH: One of the editor’s tricks is to use each angle only once. That way the impression is created that it was intended for just that moment, even if it was a choice made in the editing rooom. When Tom Cruise breaks into the CIA in Mission: Impossible, the action is taking place in the vault as well as outside the vault. So the daiies are less specific. Finding the right continuity is the tricky bit.

HULLFISH: Right. And I was going to ask you about those. Those are two scenes with a ton of tension to them: breaking into the vault with a lot of cuts to close ups of drops of sweat and knives and rats and all these things that are happening and then also the high-speed rail scene.

HIRSCH: The vault scene has no music.

HULLFISH: I didn’t realize that!

HIRSCH: Breaking into the CIA is absolutely silent and Brian wanted to take EVERYTHING out. Gary Rydstrom — who’s the sound editor — had put in a little squeak for the wheel that the rope goes though as Ethan descends into the vault and Brian said, “No, no! Get rid of it.” They wouldn’t have a squeaky wheel. They would have taken care of that. So there are hardly any sound effects and absolutely no music.

Absence of music creates tension. It’s something I learned from Bernard Herrmann when I was 26 years old and I had cut a sequence in Sisters. Bill Finley plays the doctor trying to get Margot Kidder to relive a traumatic memory and he’s holding up a bloody knife to her to try to shock her into remembering. We’re on his face; we’re on his hand with a bloody knife; we’re on her face; and then we’re also on her hand as she reaches down to take a scalpel off a table nearby. So I was intercutting these various shots and it was getting faster and faster until the moment when she slashes at him with the scalpel. When [Herrmann] saw this scene and we were talking about when to add the music cue, he’d say, “Not yet. Not yet. Not yet.” And then when she slashed him is when he introduced the music. I had imagined that he would be building tension in the music up to the point of the slash. So what I thought would be the musical climax was where he started, not ended.

So I went back and I looked at North by Northwest and saw the same thing with the crop dusting scene. That whole scene — If you say to people, “Do you remember the music in that scene?” They’ll say, “Oh yeah. It was fantastic!” Well, there isn’t any. No music at all. You hear the cropduster as it comes by and Cary Grant dives into the dust and it comes after him again and then this tanker truck comes out on the highway and he goes to the highway to stop it and the plane crashes into the truck and the whole thing explodes. That’s where the music comes in.

HULLFISH: Interesting.

HIRSCH: So all that tension that you were feeling was a function of no music. So it’s a very important lesson to learn that silence is an effect also.

HULLFISH: [Herrmann] did the score for Obsession as well.

HIRSCH: Yes, yes. I think a lot of the power of the ending — I saw it recently after many, many years. I don’t watch my films because when you get to the end of a film you’d rather put your eyes out than see it one more time. When you wait 40 years to see it again, it looks different. It played a little slower than I’d remembered. I knew it was slow, but I’m looking at through today’s eyes and that’s different from back then. But what really worked for me was the ending. Really emotionally powerful. And I think a lot of that comes from the music.

HULLFISH: Did you temp music in at all?

HIRSCH: [Herrmann] wouldn’t have it. On Sisters, we temped with Marnie and Psycho and some other things. He heard one note and he jumped out of his chair and screamed at us to turn it off. That was quite something. He didn’t want any music. Knowing that, we didn’t put anything in. So we were watching the picture dry and then Hermann started to chuckle. Brian says, “What’s so funny, Benny?” It wasn’t a funny scene. “Why are you laughing?” [Herrmann] says, “I’m just thinking that I can hear all the music now and you have to wait six weeks to hear it.”

Obsession was interesting from an editorial standpoint because when we finished the picture and the producer shopped it around — it was an independent production — he couldn’t get anybody to pick it up. He showed it to all the studios and they all turned it down.

There was a wedding sequence in the original cut of the film. (SPOILER ALERT). It turns out that Cliff and Genevieve are father and daughter, so the studios went, “Oh my God! We can’t put this out.” Incest is a taboo they would not violate.

So I had the idea of turning the wedding scene into a dream sequence. We had a shot of Cliff asleep. So instead of using the establishing shot of the house where we wedding takes place, we took that out and replaced it with the shot of Cliff sleeping and did a ripple dissolve and now it’s a dream. He’s dreaming of his obsession to marry this woman as opposed to actually recording a factual event. So by substituting one shot, the producer was able to take it back and Columbia picked it up for distribution.

HULLFISH: That is a fascinating story.

HIRSCH: Changing one shot changed the whole reaction to the film.

HULLFISH: The pace of Obsession was very deliberate, but there were two places where it definitely picked up: one was a fast sequence in the back-and-forth between Bujold’s eyes and the eyes of a painting she’s looking at. And then the other one was, of course, the climax at the airport.

HIRSCH: Both of the sequences are based on intercutting. When Brian shot Genevieve creeping around the house, she’s trying to understand her childhood. He shot a long slow zoom into her eyes. And he did a long slow zoom into the portrait of her mother and I thought, well I can’t just play them back to back. So I intercut them. I thought it worked out rather well.

HULLFISH: Yes. I loved it.

HIRSCH: I have to point out to you, Steve, that this was back in the day when you couldn’t scroll a shot. So you had to cut it so that it didn’t feel like you were backing up or jumping ahead. It had to feel like one continuous motion even though you’re going back and forth between the two shots. I wanted it to feel like one long zoom — the two would comprise one long zoom. It would have been a lot easier on an Avid because if you cut short or too deep, you could roll the shot or just trim it.

On film, we had to be much more certain of where to make the cut. You were making a decision that COULD be unmade but it was not as simple as working digitally. Because of that, a premium was placed on editors who could cut in the right place the first time and not have to fiddle around. Actually, in the old studio days, pictures were cut by the studio — not by the director. The director would finish shooting on a Friday and Monday he’d be off shooting another film. The film would go to the editing department, which was usually headed by someone like Margaret Booth or Barbara McLean. Some of these department heads had enormous power. She would assign the pictures to various editors and in those days all the splices were made by hot splice, which meant that you had to cut in the middle of the frame in order to make the edit.

HULLFISH: And you would not get that frame back.

HIRSCH: Right. So if you wanted to extend a shot because you had cut it too short, your assistant would need to put a frame of black leader to make up for the frame you had dropped, to keep the length consistent with the sound and with the picture negative. The studio would count the number of black frames in your work print, and if you had too many black frames, that wasn’t good!

I mean, obviously it’s better to have a perfect film rather than a perfect work print, but I used to pride myself on not having too many unnecessary splices.

HULLFISH: Is there anything else that you bring with you from your film background to non-linear in that you are better able to see the scene in the dailies or see the structure of a scene without putting it together?

HIRSCH: I think I always had an ability to do that. It’s hard for me to separate 50 years of experience from having worked in film. I don’t know how much that played into it or not.

My first picture came out in 1970. My first computer film was 1995 so my career has been 25 years on film and almost 25 years on the computer.

HULLFISH: There’s a great long pan at the memorial tombstone at Pontchartrain Memorial Park in Obsession.

HIRSCH: That’s to show passage of time. It starts out with him building this park — you see the bulldozer moving earth and lowering the monument into place and the camera does a 360 and there’s (supposed to be) an invisible wipe so when the camera comes back around it’s 20 years later and the park is fully landscaped. It was intended to be a seamless join and look like one shot.

HULLFISH: I was thinking of it as needing that time just for the audience to absorb what’s happened in the scene before it, which is very emotional.

HIRSCH: Yeah. In any story, you need time for things to land. You need time for the audience to get things. A lot of my work now is being called in to help pictures that aren’t working. Often it’s a question of the moments not landing because they go too fast. Sometimes you have to slow down. If the audience is confused, they’ll turn off and they’ll get bored. So even if it’s fast cut, it doesn’t mean that you’re engaging their interest. It’s important to slow down and let the moments land that need to land. Then the audience will be MORE engaged even though the pace is slower.