BOOK OPENS WITH STORY ABOUT SWITCHING WIDE SHOT IN 'OBSESSION' TO CLOSE-UP OF THE STAR

"Paul Hirsch, a master of his craft," Brian De Palma begins in his endorsement of Hirsch's new book, "has written an intelligent, perceptive, compelling memoir of his editing life, from the late '60s through today. From the heights of Star Wars to the depths of Pluto Nash, if you want to know how the sausage is cut, this is the book for you. I should know, I was with him in the beginning and through our misadventure to Mars. Congratulations, Paul, for remembering all the things we forgot."

"Paul Hirsch, a master of his craft," Brian De Palma begins in his endorsement of Hirsch's new book, "has written an intelligent, perceptive, compelling memoir of his editing life, from the late '60s through today. From the heights of Star Wars to the depths of Pluto Nash, if you want to know how the sausage is cut, this is the book for you. I should know, I was with him in the beginning and through our misadventure to Mars. Congratulations, Paul, for remembering all the things we forgot."Hirsch's book was published last week, and Variety's Drew Turney posted a a brief article about it, which included some interview bits with Hirsch:

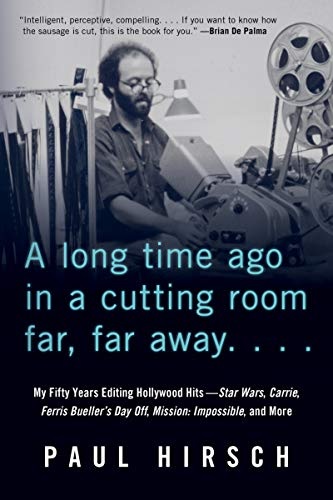

Filmgoers don’t know the name Paul Hirsch nearly as well as those of Brian De Palma, George Lucas or John Hughes, but after a five-decade career as a film editor, he’s been an integral part of some of the biggest movies ever.Hirsch says editing is a creative art despite the mechanical specialization of the pre-digital days, and his new book “A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away” (Chicago Review Press) makes a powerful case for the influence an editor can have over the creative direction of a film.

The book’s opening paragraph tells a story about how the decision to switch a wide shot to a close-up of the star in one of his early movies (De Palma’s “Obsession”) convinced Columbia Pictures to pick up and distribute the film. “Context is everything,” writes Hirsch, who along with Marsha Lucas and Richard Chew won the editing Oscar in 1978 for the original “Star Wars.” “You can take the most affecting moment of a four-hankie movie and cut it into the middle of a broad comedy, and it will seem absurd.”

But when asked about the theory some have that it’s the editor rather than the director who’s the ultimate author of a film — considering their command over the pace and therefore tone — he’s characteristically humble.

“No, it’s a collaborative thing,” Hirsch says. “I control the pace for a while. There’s a period where I’m acting autonomously. But when the director gets finished with production, we start working together to edit the film to produce the final result. At best, I’d say it’s a co-authorship, but I don’t want to give myself too much credit because I’m in the idea business. Maybe the director accepts my ideas, and I’ve been very fortunate in people endorsing my choices to a great extent, but I still wouldn’t consider myself an author.”

Hirsch likens the process to that of acting, where a performer may do 10 takes of a scene and make a different choice each time, all of it ultimately to give the director raw material.

Never one to do things conventionally, he has avoided the usual creative model where some editors and directors are inextricably linked (Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker, Quentin Tarantino and Sally Menke, Steven Spielberg and Michael Kahn, etc.). He calls such unions “happy marriages,” but says in his book that he prefers to “sleep around,” taking it as a point of pride when directors invite him back.

The book makes readers realize what an unsung art editing is. But Hirsch says his intention in writing it — he’s been scribbling notes for it over the last 18 years — isn’t to teach. “It’s really about explaining what it is to be an editor, what kind of life you have if you’re an editor,” he says. “I’m not really interested in how-to books. My aim was to entertain people, tell them a good story and explain what we do.”

Updated: Monday, November 11, 2019 7:55 AM CST

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post