"HOW DISNEY'S MISSION TO MARS WENT FROM ATTRACTION TO BRIAN DE PALMA MOVIE BACK TO ATTRACTION"

Yesterday at Collider, Drew Taylor posted an article about Disney's "Mission To Mars" attraction. "45 years ago today Mission to Mars opened at the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World," Taylor begins. "The attraction, which simulated the experience of blasting guests to the red planet, would [have] an oddly lasting effect on the company, inspiring a poorly received film that in turn would serve as the basis [of] an equally mediocre attraction. And on and on it goes, like the rotation of some huge planet. For some reason (and for many years), its gravitational pull was too great."

Here's a further excerpt from Taylor's article:

In June, 1975, Mission to Mars was first launched. It featured many of the same animatronics and even some of the same footage in the pre-show and ride film, but new elements were made to the show itself, both in terms of effects (inflatable seats would be inflated or deflated, to simulate space travel) and story points (hello, hyperspace travel). In 1975 Mission to Mars was installed in Disneyland too. But by the early 1990s, it was starting to show its age. It lacked the visceral thrills and excitement that modern audiences demanded and much of the science and technology was outdated and creaky. It closed in 1992 in Disneyland and 1993 in Walt Disney World. The mission had come to an end.Or had it?

Since the late 2000s, Disney had been noodling with the idea of turning some of its beloved theme park attractions into equally beloved big screen events. The test pilot was Tower of Terror, a 1997 horror comedy starring Steve Guttenberg and Kirsten Dunst that aired on Wonderful World of Disney and, more crucially, acted as an 89-minute commercial for The Twilight Zone: Tower of Terror, an innovative attraction that opened at what was then known as Disney-MGM Studios a few years earlier. (Part of the movie was actually filmed at the attraction in Florida. At the time MGM-Studios took pride in the fact that it was a fully operational production studio, even though hardly anything was ever shot there.) The movie was enough of a hit that several other projects inched through development, among them were big screen adaptations of Pirates of the Caribbean and The Haunted Mansion, along with Dinosaur, an animated film that was using state-of-the-art technology and was being developed alongside an attraction set to open at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. Ah, synergy.

But the film that would ultimately make it out of the gate first was Mission to Mars. Part of this had to do with an arms race Disney was having with Warner Bros, who was developing their own Mars-themed project called Red Planet. (A couple of years earlier Disney had found itself in a similar situation as its own Armageddon squared off against Paramount and DreamWorks’ Deep Impact.) And part of it had to do with the fact that the studio really didn’t publicize that it was based on the theme park attraction, which at the time had been shuttered for the better part of a decade. The movies-based-on-theme-park-attractions idea appealed to Disney chief Michael Eisner but it still made him nervous. It was Eisner who made the last-minute decision to add the cumbersome subtitle to Pirates of the Caribbean in an effort to distance itself from the attraction. If Mission to Mars was a success, so be it. But the connections between the theme park attraction and the movie were not going to be explicitly drawn.

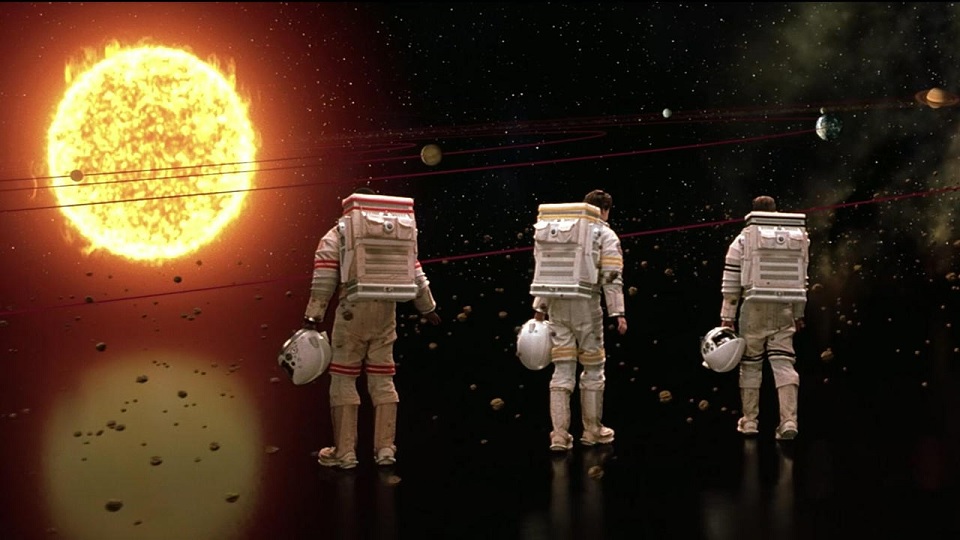

And, truth be told, the movie, directed by Brian De Palma from a screenplay officially credited to Jim and John Thomas and Graham Yost, doesn’t have a whole lot to do with the original attraction. Sure, it’s about an expedition to Mars. But there aren’t any direct parallels to be drawn, save from that amazing long shot, set to Van Halen’s “Dance the Night Away,” which features a rotating circular centrifuge, that explicitly recalls a similar image on one of the screens in the Mission to Mars preshow. (It’s a deep cut, I know.) Where there could have been references, there are emphatically not. You’d think that some of the characters could have had the last name “Morrow” or “Johnson,” references to the audio-animatronic figure that gave you the rundown in the ride’s pre-show. But, alas, there is none. De Palma, whose experience on the film wasn’t particularly positive (“It was relentless,” he said in the De Palma documentary), never mentioned the original attraction. It’s unclear if he even knew the film was an adaptation of a popular theme park attraction.

When Mission to Mars came out in the spring of 2000 (happy 20th!), it lost money, making $111 million internationally from a budget of over $100 million. De Palma was so broken by the project that he left the United States. “The Hollywood system we work in does nothing but destroy you,” De Palma said in the documentary. “When I finished that movie, that’s when I got on a plane and went to Paris. Mission to Mars was the last movie I made in the United States.” (Mission to Mars did get some strong notices from critics, particularly overseas. It was #4 on Cashiers du Cinema’s collective Top 10 that year, outranking The Virgin Suicides and In the Mood For Love.) But box office be damned, Mission to Mars was going to live on.

EPCOT had wanted a space pavilion since the early 1990s. It made sense. EPCOT (formerly EPCOT Center) was the science and discovery park. Space should have always been there. Initial plans called for a giant pavilion wherein several attractions would be accessible (one would have simulated a spacewalk, with guests suspended from an overhead track, peering into the outside of a space station) but budget cuts and the popularity of Horizons, a sort-of space-themed attraction about futuristic communities, occupying the same land that the new pavilion would have been placed, meant the space pavilion was off the table. But the idea was being revisited at the close of the decade; Horizons had lost its corporate sponsorship and a large sinkhole had been detected underneath its massive show building. They could finally do the really-for-real space pavilion and they had a cutting-edge idea to go along with it: spinning centrifuge that would make you feel weightless. They also had a flashy Disney movie they could piggyback on: Mission to Mars.

Disney enlisted Gary Sinise, one of the stars of Mission to Mars, to host the preshow for the new attraction, now called Mission: Space. (Sinise essentially is playing the same character but his name is never spoken.) And the big, wheel-shaped room from the “Dance the Night Away” scene is actually a part of the attraction’s extended queue, along with several model spaceships from the film (much of the visual effects work for the movie was provided by Dream Quest Images, Disney’s in-house visual effects company, that was shuttered following Mission to Mars’ release). On a narrative level, this new attraction borrowed heavily from the Mission to Mars attraction, including the conceit that you are being trained to make the journey to outer space and the patina of pseudo-scientific education. But this time the emphasis was on thrills.

So Mission to Mars, a movie inspired by a Disney theme park attraction, inspired another Disney theme park attraction. Moving in a circle, just like the astronauts in the movie. Who has the Van Halen?