TO HELP SEE HOW HE COULD DO LONG TAKES WITHOUT BEING "SHOWY" IN 'KILLING OF TWO LOVERS'

MovieMaker's Caleb Hammond interviewed writer-director Robert Machoian about his newly-released film, which Nicolas Rapold mentions in his New York Times review is "told in unpredictable long takes." --

The Killing of Two Lovers writer-director Robert Machoian thought a lot during the planning of the film about “how to shoot long takes without drawing attention to the fact that it’s a long take, in and of itself.”So he went back and watched Brian De Palma’s Snake Eyes for its flashy 12-minute single take opening.

“It’s very showy. And there’s a place for that. But for this film, it would have been very inappropriate to be showy at all,” he says.

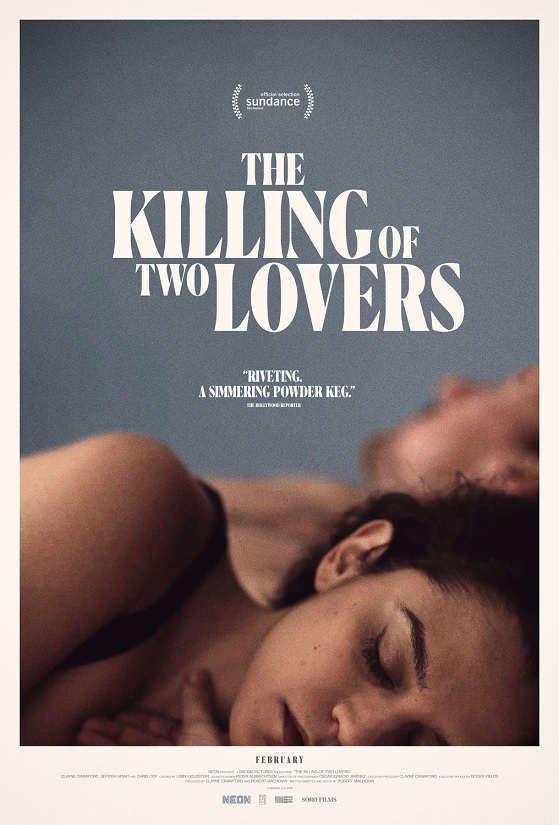

The Killing of Two Lovers follows married couple David (Clayne Crawford) and Nikki (Sepideh Moafi) in rural Utah, as they work through a separation. But after Nikki gets a boyfriend (Chris Coy), David begins to unravel.

The film makes masterful use of long takes throughout, and Machoian and cinematographer Oscar Ignacio Jiménez employ it much differently than De Palma did for his Nicolas Cage conspiracy thriller. In one key moment, the camera acts as an equalizer during an emotionally fraught scene.

Avoiding traditional shot-reverse-shot coverage, the camera is instead framed on both David and Nikki as they work through an argument. This prevents the audience from choosing a side.

“The second you hold the camera, you establish that somebody is more important than the other,” Machoian explains. “But David and Nikki are equally trying to figure this out. And there really isn’t one who is in more of a position of power than the other.”

Crawford, Moafi, and Coy all have theater experience, which made pulling off these extended sequences possible. “If we didn’t have the actors that we had, we would have had to shoot it differently. Because if you do a long take with someone who can’t act, it just gets worse the longer they go with it — it doesn’t necessarily get better,” Machoian says.

Machoian is aware that long takes can be distracting to viewers.

“It felt really important to just orchestrate the performance, and allow Sepideh and Clayne to move within that frame, and as a result, hopefully not draw attention to the fact that we’ve been sitting on this shot for four minutes,” he said. “Hopefully in the end you’re so engrossed in the character drama, that it’s really kind of an afterthought.”

Filmmaker Magazine's Erik Luers also interviewed Machoian:

Filmmaker: And in the final sequence, where a big argument and altercation takes place, I read that you were stationed in a golf cart tracking the action off-screen?Machoian: That’s right. I’ve made films in the past that explore duration, sometimes duration for the sake of duration and sometimes duration due to the scene being interesting enough to force the viewer to stay in the scene and watch the arc and feel a bit trapped. While I wanted most of the scenes in The Killing of Two Lovers to primarily be two-to-three-minute one-takes, I wanted the final argument to be one long take (I can’t remember anymore if it’s seven or nine minutes). It didn’t feel right to remain static (as we had throughout the film) for that sequence. We had used a golf cart in the opening sequence of the film (where David is running from house to house), but it wound up blowing a tire while we were shooting due to how cold it was outside. We had to get the tire fixed and that took some time.

Once the tire was fixed, we used the golf cart again to shoot the final fight scene, something we shot about two days before production concluded. We didn’t have the golf cart available for any other period of time until we were able to get the tire fixed. Once it was and we knew we wanted to use it for the final fight, I told Oscar, “Look, the best way for us to do this is for you to run the camera and be framing the scene constantly”—we obviously discussed the type of framing, etc.— and “I’m going to be the one driving you on the golf cart.” I drove the golf cart, moving forward slightly depending on how the arc of the drama was unfolding between the actors, i.e. as David begins to feel isolated, I push in farther so that we could, in many ways, isolate the viewer, too, or, as David and Nikki have that brief moment together (the “calm before storm”) where he’s struggling and she realizes he’s struggling and she loves him and feels sorry for the fact that he’s struggling, and then BAM! Then the camera begins to pull back again.

It was very difficult to get right, not the least because the wheel we had gotten fixed was now constantly squeaking! And since the tension present in the scene was so high, the squeaking wheel threatened to be a real distraction for the actors. I had to be like, “I’m so sorry, this will squeak, but we need to do it this way. We can’t walk it and we can’t all of a sudden switch to handheld.” We didn’t have access to a dolly, and so I pleaded with my actors, “I need you to go with me on this,” and luckily they trusted me. When they came to watch the dailies that night, they were like, “This is amazing,” and I thanked them. For emotional purposes, we needed to have the camera establish some distance. We’d used wides and closeups for the majority of the movie, but this was the place where we needed to move in and out of those wides and closeups.