"DESPERATE SOULS, DARK CITY AND THE LEGEND OF MIDNIGHT COWBOY"

At Roger Ebert.com, Charles Kirkland Jr. reviews Desperate Souls, Dark City and the Legend of Midnight Cowboy:

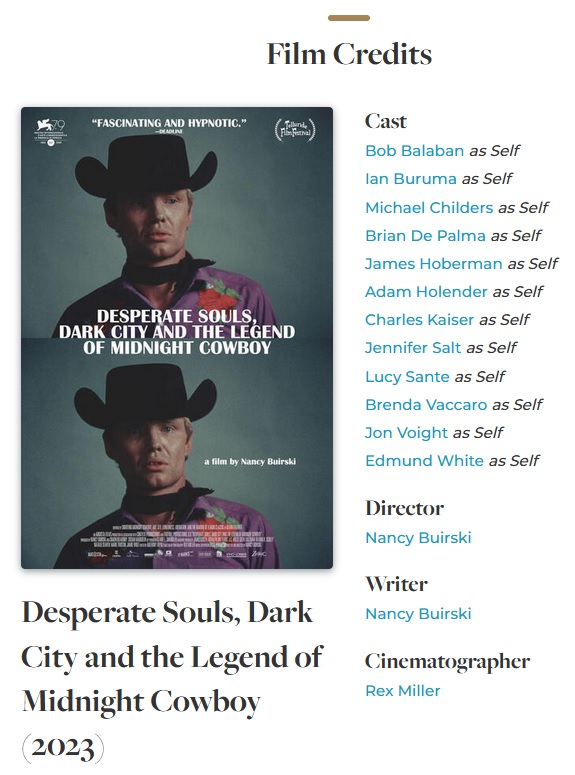

Wrapped loosely in the packaging of a documentary, "Desperate Souls, Dark City and the Legend of the Midnight Cowboy," is written and directed by Nancy Buirski. It features Jon Voight, Bob Balaban, Brian de Palma, Charles Kaiser, Lucy Sante, Brenda Vaccaro, the voice of John Schlesinger, and many others who either were in "Midnight Cowboy," involved in its production, or were admirers of the film.When the documentary opens with a closeup of Jon Voight, recalling an existential crisis by director John Schlesinger after the completion of "Midnight Cowboy," the film almost implicitly states that it will be about the creation of that film. Yet, "Desperate Souls" only lightly touches on the creation of "Cowboy." Instead, this film spends most of its time investigating the era during which it was made. "Midnight Cowboy" lived at the nexus of a war, the civil rights movement, and the early beginnings of the gay rights movement.

Variety's Owen Gleiberman reviews the film more favorably:

A movie, good, bad or indifferent, is always “about” something. But some movies are about more things than others, and as you watch “Desperate Souls, Dark City and the Legend of Midnight Cowboy,” Nancy Buirski’s rapt, incisive, and beautifully exploratory making-of-a-movie documentary, what comes into focus is that “Midnight Cowboy” was about so many things that audiences could sink into the film as if it were a piece of their own lives.The movie was about loneliness. It was about dreams, sunny yet broken. It was about gay male sexuality and the shock of really seeing it, for the first time, in a major motion picture. It was about the crush and alienation of New York City: the godless concrete carnival wasteland, which had never been captured onscreen with the telephoto authenticity it had here. The movie was also about the larger sexual revolution — what the scuzziness of “free love” really looked like, and the overlap between the homoerotic and hetero gaze. It was about money and poverty and class and how they could tear your soul apart. It was about how the war in Vietnam was tearing the soul of America apart. It was about a new kind of acting, built on the realism of Brando, that also went beyond it.

And it was about love. Jon Voight’s Joe Buck, that rangy Texas good ol’ boy with his fringed buckskin jacket and his jutting-front-teeth grin and his sexy bright naïveté, and Dustin Hoffman’s Ratso Rizzo, sweaty and unshaven, long hair greased back, hobbling through the streets, hording his change in a shoe with a hole in it and no sock — these two had nothing in common except that they were losers, hanging by a thread, and only after a while did they realize that they had nothing in the world but each other.

The risky, offhand greatness of “Midnight Cowboy” is that the movie, while it knew it was about a lot of these things, also didn’t know it was about a lot of these things. More, perhaps, than any other formative New Hollywood landmark (“Bonnie and Clyde,” “The Graduate,” “Easy Rider”), the film channeled the world around it. “Desperate Souls, Dark City” tells the story of how “Midnight Cowboy” got made, and how the people who made it — the director John Schlesinger, the screenwriter Waldo Salt, Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman, and James Leo Herlily, who wrote the 1965 novel on which the film was based — took the essence of who they were and poured it into a personal vision of what we were seeing onscreen.

As a documentary filmmaker, Nancy Buirski (“By Sidney Lumet”) comes at you from a heady impressionistic angle. For all its tasty anecdotes, and there are lots of them, “Desperate Souls” is less concerned with production war stories, with the everyday nuts and bolts of how “Midnight Cowboy” got made (we see the famous scene in which Ratso bangs on a car and shouts “I’m walkin’ heah,” but don’t get the usual story about shooting the scene), than with the emotional metaphysics of how a movie about a blinkered hustler and a homeless loser came to embody what Hollywood was becoming: not a dream factory but a truth factory, an eerie moving mirror of who we were.