REVERSE SHOT TO CELEBRATE ITS 20TH ANNIVERSARY WITH DE PALMA'S FEMME FATALE

"Originally printed as a stapled zine," begins the film series description at Museum of the Moving Image, "distributed for free throughout New York, the independent film journal Reverse Shot began in 2003 as a labor-of-love endeavor among a small group of twenty-something cinephiles. Since 2014, it has been the house publication of criticism for Museum of the Moving Image, still edited by two of its co-founders, Michael Koresky and Jeff Reichert. Reverse Shot has stayed committed to publishing serious, lively, and thoughtfully edited writing that wrestles with the past, present, and possible future of the cinematic medium. On the occasion of its 20th anniversary, MoMI and Reverse Shot team up to give audiences an opportunity to see some of its contributors’ favorite films from the 21st century on the Museum’s big screen."

While the film series opens Friday night (Sept. 22) with a screening of Olivier Assayas' Demonlover, this Saturday night's screening of Brian De Palma's Femme Fatale is paired with the Reverse Shot Anniversary Reception, which will take place in the lobby after the movie.

Here's the Museum's description of Femme Fatale:

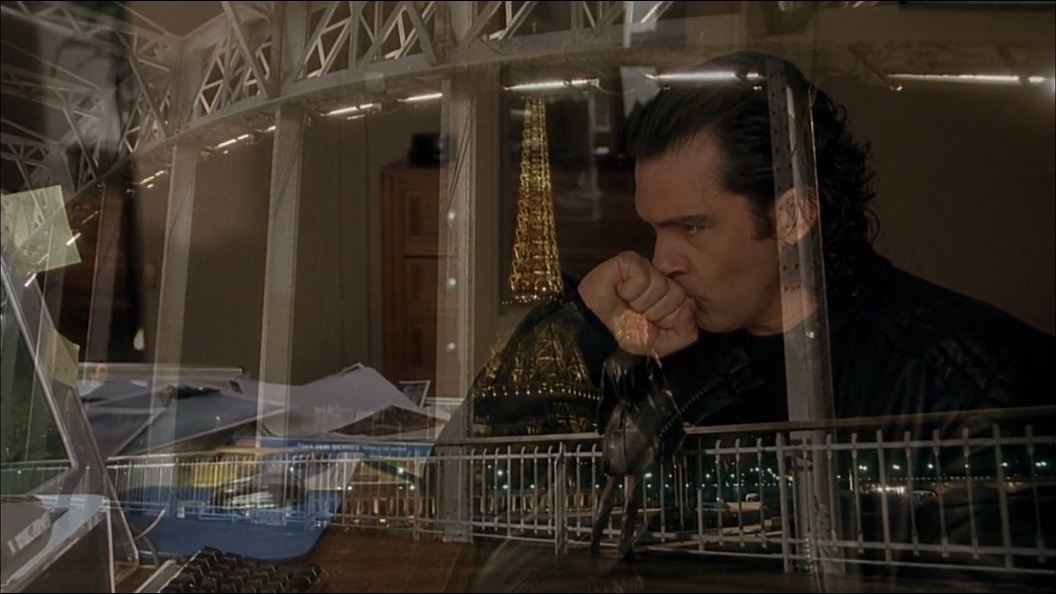

De Palma’s silky, seductive, ridiculously entertaining meta-noir stars a delightful, committed Romijn-Stamos as a statuesque jewel thief on the run from her fellow criminals after absconding with a stash of diamonds. Yet that simple description could not prepare a first-time viewer (or, frankly, even a tenth-time viewer) for the ecstasy of De Palma’s endlessly looping, self-referential, too-pure-for-camp masterwork, a film that’s a dose of giddy pleasure from its intricate opening heist scene set during the Cannes Film Festival (!) to its mind-bending split-screen shenanigans to its wild alt-reality conclusion.

Here's an excerpt from Chris Wisniewski's 2006 Reverse Shot essay about Femme Fatale:

The entirety of the film hinges on the ability to make sense of visual information and to see things as they are, which is why it’s so brilliant that De Palma constantly puts us in the position of misrecognizing what we’re seeing, despite giving us the clues. Those are the diamonds; that is her conspirator; this is a dream. You just didn’t see it. Fittingly, Laure finally gets the better of the men who are hunting her thanks to literal blindness—a flash of sunlight, refracted through a piece of jewelry, blinds a truck driver who drives the men into the spikes of a metal grate, a most violent and lethal penetration. De Palma, like Hitchcock, is perpetually concerned with the idea of “the gaze”—the gaze of the camera, of the spectator, and of the straight male (all of which may be, in some sense, variations of the same thing)—and with disrupting the equation that to look is to see; to see is to know; and to know is to have power.Shortly before she seduces Nicolas, Laure does a short striptease for a man in the basement of a bar, as Nicolas watches from the other side of the doorway. We see most of the striptease from Nicolas’s point-of-view, as though she’s dancing for his benefit and, by extension, for ours. It’s pure titillation, a softcore cinematic masculine fantasy. Then De Palma turns everything around. The other man loses control and lunges at her, and Nicolas, perhaps out of jealousy or some masculine impulse to protect Laure, jumps and attacks him. We watch her watching them, the fight visible only as a shadow play on the wall. They do their little masculine dance, and she spectates with delight, applauding as it reaches its climax. Perspectives shift—the looked-at does the looking; power dynamics are reconfigured. Fetish becomes critique in this deadly game of transmuting identities and shifting realities, a veritable cinematic hall of mirrors.