AND DE PALMA'S SEARCH FOR PURE CINEMA IN MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE

As we remember David Bordwell, who passed away this week after a long disease, we're looking back at Bordwell's Observations on film art post from 2014 about visual storytelling, which focuses on Brian De Palma's Mission: Impossible:

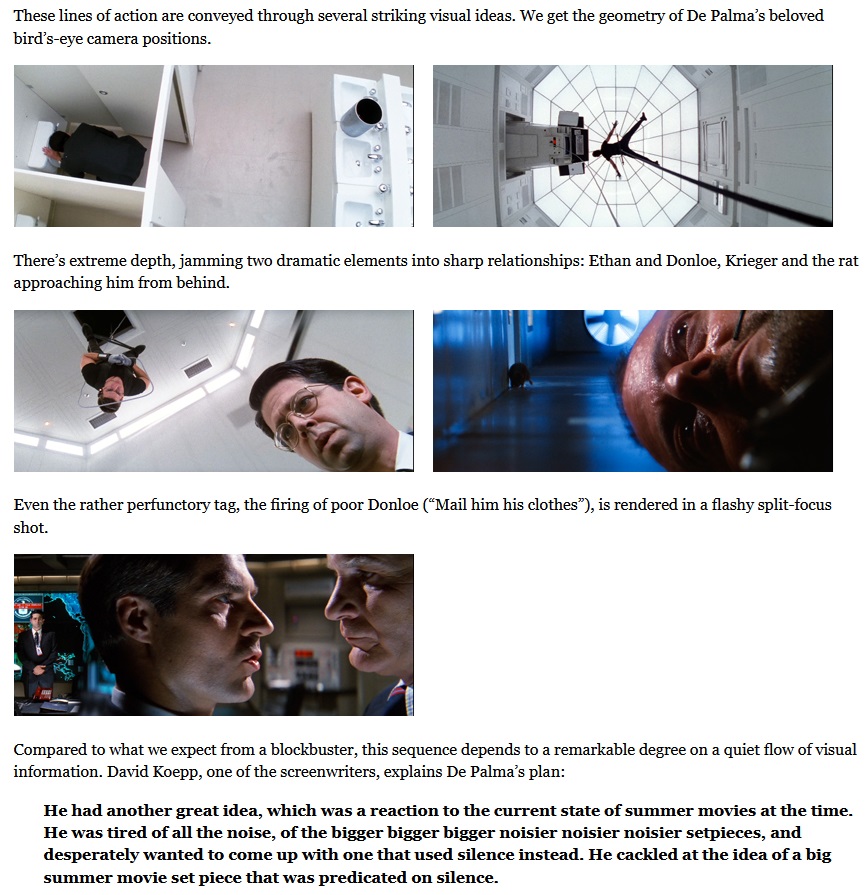

The result is nice case study in visual storytelling. It also indicates how even a pure instance needs non-visual elements to be understood.Top among those elements is genre. We know a heist situation when we see one, and that knowledge forms a kind of hollow form, a schema into which we slot the elements that generate suspense. What elements? There’s the need for silence and concealment. There’s Donloe, the oblivious analyst who comes in and out of the vault; he must be distracted, but he may still return at the wrong moment. There are unexpected obstacles—a suspicious guard, a curious rat, and a drop of sweat. There’s the risk of a telltale detail that may betray the invaders, such as Krieger’s dagger, dropped onto an arm rest. Over it all hovers a deadline, so that the heist becomes a race against time. (Not only is there a clock in the room, but a digital readout warns us of the rising temperature in the room, another potential giveaway.) Visual storytelling is enormously helped when we bring so much prior knowledge about the type of situation we confront.

“From here on in,” Ethan warns the team, “absolute silence.” For them, maybe, but not for us. The music continues a bit before subsiding for about ten minutes. Even then, the silence isn’t absolute. We hear the hum of the vault, the scratchy patter of the rat approaching Krieger in the ductwork, and the squeaking of the rope as Krieger pays it out and strains to keep Ethan poised above the floor.

Clearly, in his concern for visual storytelling De Palma isn’t ruling out noise and music. What he’s opposed to is talk. But there is talk, however discreet, here too. In M:I, I count about two dozen lines of dialogue once Krieger and Ethan get positioned above the vault. These chiefly involve Luther whispering information to Ethan about Donloe’s whereabouts. Granted, many of his lines are very terse (“He’s in the bathroom,” “Check,” “Good”). Still, dialogue serves as a good redundancy factor, accentuating the suspense of the situation and at one moment giving us access to Luther’s reaction, when he discovers that what Ethan has nabbed is the precious NOC list.

Just as important, our experience of the full suspense of the scene depends on talk we’ve heard earlier. Ethan has gathered his team on the train and is explaining how the security system at Langley works. Using a strategy that goes back to Lang’s M, M:I presents Ethan’s verbal walk-through of the procedures as a voice-over for footage of Donloe executing them. The sequence introduces us to Donloe, familiarizes us with the constraints of the heist, and maps out the normal going-and-coming rhythm that Donloe’s spasmodic upchucking will disrupt.

So the vault break-in can rely on relative silence partly because the situation has been given fully by Ethan’s verbiage. In a way, it’s the reverse order of the Rear Window tutorial: dialogue first, then images to give it dramatic impact.