JOHNNY RESTALL AT DREAD CENTRAL, GLENN KENNY AT DECIDER

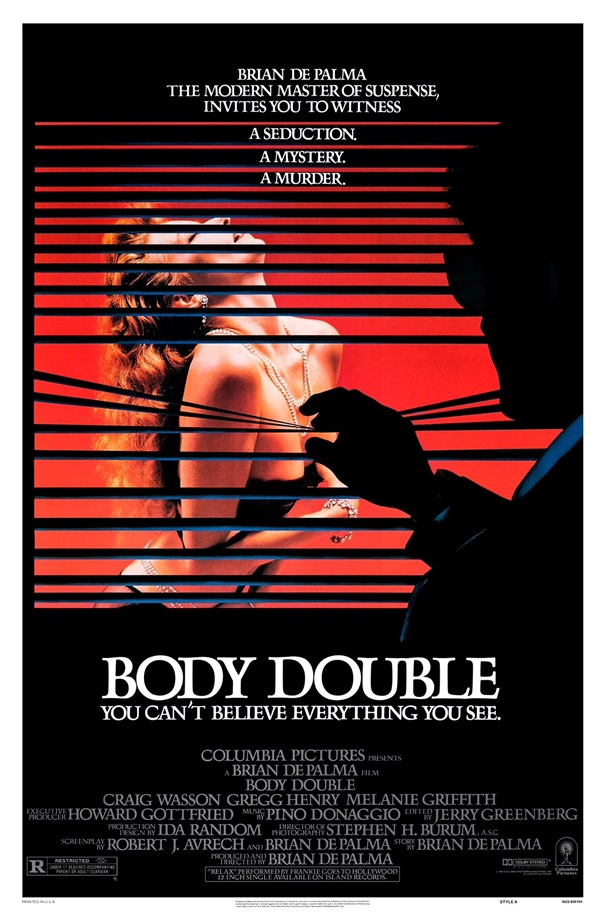

As Body Double turned 40 this past weekend, several posts looked back on Brian De Palma's classic. Here's a couple of samples:

As in Sisters (1972), Obsession (1976), and Dressed to Kill, De Palma draws on Hitchcock’s style and themes in order to create sly pyrotechnics that are entirely his own. If the initial scenes of Jake stalking Gloria nod towards Vertigo (1958), they soon build into an extraordinarily well-choreographed ballet once they reach the Rodeo Collection mall. Largely free of dialogue, and almost entirely carried by movement and Pino Donaggio’s opulent score, it’s a jaw-dropping tour-de-force, playing with geography and perspective. Stephen H. Burum’s stunning camerawork moves up and down and left to right, using every inch of the space while tightly controlling what it wants us to see.Sometimes we know more than the characters (as when we see the ‘Indian’ or the security guard sneak by), and sometimes we’re left as shocked as Jake by a sudden reveal. It’s an astoundingly involving sequence, particularly considering that nothing especially dramatic happens. Admittedly, it draws on Hitchcock’s techniques, but even he was rarely so deliciously audacious in scale, nor so fearless in displaying his own mischievous sleight of hand.

Most controversially, the mall scene and indeed the first half of the film revolve around a man spying on an attractive, troubled woman. Rather than play the scenes subtly, De Palma amps up the slick eroticism to cartoonish levels, as if determined to enrage those who’d considered Dressed To Kill too leering and sexist. Of course, the most implausible and overtly sexualized moments are when Jake watches ‘Gloria’ dance at her window, and these are later revealed not to be her at all. However, it’s left for the viewer to decide whether these deceptive performances by adult actress Holly Body (Melanie Griffith) are a comment on the ludicrousness of straight male fantasies, or whether they’re simply a further example of the unrepentant male gaze in cinema.

Certainly, while she has a broadly similar character arc, Shelton’s Gloria remains passive and underdeveloped compared to Angie Dickinson’s Kate in Dressed to Kill, and the scene in which she kisses Jake despite knowing he’s been following her is ridiculously unlikely (if typically stylish). Likewise, although De Palma has always denied it was intentional, Gloria’s death by drill at the hands of her estranged husband has distinctly phallic overtones, as if designed to enrage feminist critics.

Yet judging these moments in isolation overlooks their context and the deliberate contradictions that run throughout the film. If Gloria’s murder is both horrifying and exploitative (a dichotomy at the heart of all horror cinema), her killer is never portrayed as anything but repugnant. Sam Bouchard (Gregg Henry) exudes arrogance, full of untrustworthy bonhomie and casual misogyny as he ensnares the meek Jake in his schemes. His contempt for others is made chillingly clear by the shot of him standing over Gloria’s body, hands on the drill and foot on her throat, his ‘Indian’ disguise adding blithe racism to his repulsively entitled characteristics.

Further, to suggest that the murder fits with the perceived slasher trope of “punishing” sexually active women is to overlook who replaces the deceased as the new female lead. Like Liz (Nancy Allen) taking Kate’s narrative place in Dressed to Kill, the second half of Body Double belongs to Holly Body—an assertive, strong, and sexually uninhibited woman rather than the traditional virginal ‘good’ girl.

While De Palma plays with puritanical audience expectations, he seems to delight in confounding them. Whether the role of a forthright adult film star is progressive or just more male fantasy is debatable, but it certainly suggests that the director’s world is more complex than the conservative standard attributed to certain slashers. (The fact that he had already spoofed the genre at the start of Blow Out and appears to reference Amy Jones’ 1982 The Slumber Party Massacre with Sam’s choice of murder weapon further implies a playful awareness of the pleasures and limitations of the form.)

Perhaps the most provocative and confrontational aspect of Body Double is the way its games implicate us as viewers. De Palma knows that voyeurism is the essence of cinema, and the more transgressive the sights, the better. Like Jake spying on Gloria/Holly from the dark of his apartment, we know we should look away—but we can’t. It’s no accident that the prominent line of dialogue during the porno movie shoot within the film is “I like to watch”. Nor is it a coincidence that just before showing Jake the telescope that sets the plot in motion, Sam proposes a toast “to Hollywood”.

Indeed, the film’s gleefully tawdry thriller plot is arguably a trojan horse disguising a caustically witty commentary on the dreams and disappointments of Tinsel Town. It emphasizes the tedium and hard work of trying to make it: enduring hostile auditions, attending pretentious acting classes, and surviving the trials and tribulations of cheap B movies like the opening sequence’s Vampire’s Kiss. The film is littered with L.A. landmarks, from the Capitol Records Building and Tail O’ The Pup to the Chemosphere that serves as the location for Jake’s adopted home. By locating its violent climax at the L.A. Aqueduct Cascades, it places the sex, danger, and illusion of the plot on an equal footing with the water supply, as though all these elements are essential to the city.

Glenn Kenny, Decider

But the sexual content with which De Palma packed Body Double is potent. He chose Melanie Griffith, then in her mid-twenties, to play porn star Holly Body. He’d met the daughter of Hitchcock star Tippi Hedren while making Scarface; she was the girlfriend of actor Steven Bauer, who plays Tony Montana’s lieutenant Manny in the movie. And Double contains a funny Scarface in-joke. Bauer appears here as one of Holly’s sexual partners in a scene from Holly Does Hollywood, one of Double’s porno-films-within-a-film. He comes into a small room where Holly sits, prepared to do her oral stuff, and is interrupted by a voice on his walkie-talkie saying “Manny, where the hell are you? We need you on set.”Body Double’s plot is a gloss on Hitchcock’s Rear Window, with some morbid femme obsession from Vertigo tempered in. During the height of his career De Palma got a lot of critical smack for his lifts from Hitchcock, but that was unfair. He didn’t take cues from Hitchcock because he was bereft of his own ideas; he did because he knew that the stuff could be constructively and pertinently updated in explicit contemporary terms. In crude terms, it meant he got show things that Hitchcock never could. But it also meant he could make the subtexts in Hitchcock bubble up to a mordant surface.

Heights are the hero’s fear in Vertigo; in Body Double Jake Scully is claustrophobic, which makes his time in a coffin as a glitter-rock vampire (shades of De Palma’s early ‘70s quasi-glam musical Phantom of the Paradise!) in the movie’s opening less than tolerable. He freaks out, gets fired from the schlock movie he’s acting in, and now he’s got an impediment that he has to conquer in his hero’s journey. This journey finds him accepting the generosity of a fellow actor, who sets him up in a crazy ultra-modern UFO-like house in the Hollywood hills; across the way is another house with large horizontal windows and loosely space vertical blinds, and in that house a very scantily clad young woman dances with a remarkable lack of inhibition. Nice for Scully that the joint where he’s housesitting has a top-brand telescope. It’s almost too convenient, right?

And here, for all the rampant sex, corrosive inside-moviemaking humor, and general impertinent attitude, is where we hit the Problematic, in what, it happens, is the movie’s only murder. Given its grisliness, one is all Body Double needs.

Updated: Thursday, October 31, 2024 12:27 AM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post