THE REAL MONSTERS IN THIS MOVIE "CONVINCE YOU TO SELL YOUR SOUL FOR WHAT IS ALREADY A NATURAL TALENT"

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | November 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Remastered CD reissue.

12-page CD booklet with liner notes by Daniel Schweiger.

Limited Edition of 1000 units.In collaboration with Edward R. Pressman Film Corporation, Music Box Records proudly follows their IFMCA award-winning release of Bernard Herrmann’s 1976 Oscar-nominated score for Obsession by now going back to his collaboration, one that relaunched his career as well as boldly announcing a new Master of Suspense. Almost forgotten when editor Paul Hirsch was inspired to use Psycho as temporary music, the resulting collaboration between him, filmmaker Brian De Palma and Herrmann showed just how much diabolically inventive energy was left to his talent with 1973’s Sisters.

Weathering the storm that the legendarily combustible musician brought to this tale of an innocent model and her possession by a seemingly dead twin (both played by Margot Kidder). The result of Herrmann’s outraged inspiration was one of his great, theme-filled scores. Particularly striking as it brought a new Moog electronic sensibility to join with his symphonic swings between romance and terror, Sisters once again brought the composer into the Hollywood eye while joltingly announcing the arrival of a stylistically fresh, homage-filled auteur of modern suspense cinema.

With Sisters’ complete scoring session elements proving lost after an exhaustive search in collaboration with the Edward R. Pressman Film Corporation, Music Box Records has painstakingly remastered the original CD edition to reprise its original album program with a knife-striking, bell-ringing orchestral malice that no mad doctor can rend asunder. Extensive liner notes by Daniel Schweiger (Obsession) features a new interview with Paul Hirsch on the turbulent scoring process with Bernard Herrmann that brought an iconically thrilling legend back to Hollywood life. The CD release is limited to 1000 units.

Mary-Ann Vaillancourt was 10 years old when the film premiered. She remembers coming to the now-defunct Garrick Theatre with friends to watch it."I stayed for two shows," she said. "And I did it again the next weekend. And I did it every weekend that I was allowed to come out."

Vaillancourt was one of the hundreds of people who showed up for the latest "Phantompalooza," a local event that, this year, marked the film's 50th anniversary.

Craig Wallace, a member of the Phantom 50th committee, said the two planned screenings of a restored version of the film sold out in a day and a half. A matinee, also featuring a Q&A with cast members, was added to meet the demand.

"Winnipeg has brought a lot of people from other provinces here, and they see what we see," said Dean Hunter, singer with Phantom tribute band Swanage, who's also on the committee.

"They might be from all over the world, but they love this movie as much as we do. And we just like to share it with them."

The celebration brought back a lot of memories for fans who attended the matinee Saturday.

Betty Moroz, from Garson, Man., was 14 when she first watched it.

"I thought it was kind of freaky back then," she said, but it stuck with her.

"It's very powerful, very moving. The music, the love and, what you would do for love. Anything for love."

"I have two copies at home," said Stephanie Starr, who came to the screening with her family.

"We love it. We've seen the movies many times before. And of course, you got to get the merchandise, right? I got a couple of buttons."

For other Winnipeggers like Tom Glenewinkel, the matinee was the first time they've actually seen the film.

"Everybody knows all the words to everything," Glenewinkel said. "It was just a great movie to watch, and just to be part of the experience of everybody enjoying it and getting into it."

Vaillancourt brought a C.D. of the movie's soundtrack to the matinee and newspaper clippings about the film she kept with her over the years. V She hoped to meet Paul Williams — star and composer in the film — who decades ago replied to her fan letter. V "'Dear Mary-Ann, thank you for your letter telling me how much you enjoyed Phantom.… P.S. I think I've only seen the movie about four times myself,'" Vaillancourt read, saying that at that point she'd seen the film about 10 times already.

"He made my whole day and my whole summer," she added. "The music is still phenomenal now, and I still listen to it if I want to just be able to sing along, every single word."

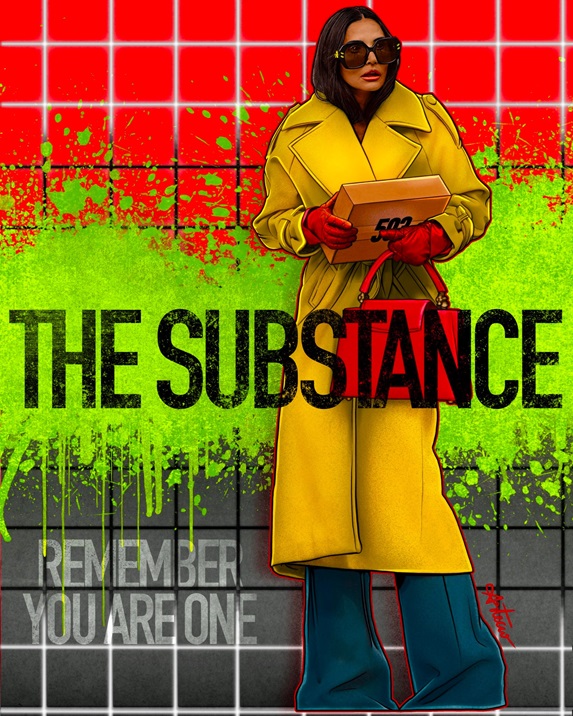

Fargeat has always gravitated towards a smorgasbord of different genres, including “action, Westerns, horror, body horror, sci-fi, fantasy”. The filmmaker tells me that she adored “everything that allowed me to go outside of reality and be in a world where the rules were different and were a great window to creative, often crazy imaginations. It goes from the first Star Wars trilogy to the movies from [David] Cronenberg, which had a big impact on me.” She also cites Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop and the surrealism of David Lynch: “They all played specific roles at different ages of my life, building my imagination and my way of envisioning the world.”Growing up in France, Fargeat recalls feeling “quite bored” and that everyday life was “inadequate”; the entertaining adventures and “sense of rebellion” in genre films provoked “strong emotions, whether it was fear, passion, thrill… I was feeling alive.” Dark comedy played a large role in her cinematic coming-of-age as well, particularly the silent satire of Charlie Chaplin. “It’s really two legs that I have with me,” she says. “The more genre, imaginative one, and the more satirical comedy—which is also something that creates strong emotions.”

In The Substance, satire converges with body-horror to metaphorically metamorphosize into its own beast. Fargeat lists Cronenberg’s The Fly as a definite inspiration for the literal metamorphosis featured in her film, as well as the enduring imagery of the blood tsunami pouring out of the elevator in The Shining, and, of course, the climactic prom scene from Carrie. (While the filmmaker admits that she hasn’t yet seen Society, it’s now on her watchlist since so many people have mentioned it after witnessing her penchant for grotesquely organic practical effects).

“All those movies, filmmakers have seen the work of other filmmakers who’ve digested what they’ve seen and what other filmmakers did,” Fargeat says. “I love the fact that there is some kind of common creativity somewhere that each one redigests in its own way, with its own world and its own theme. I truly believe that we are, in the end, the result of what we watch, what we read, what we’re exposed to, and all of this lives with us… We are growing ourselves, feeding ourselves from all those influences, whether they are conscious or unconscious.”

"I JUST GOT CAUGHT UP IN THE VIBE THAT IS BRIAN DE PALMA"

A great read over at Bloody Disgusting: "The Phantom Lives: An Oral History of ‘Phantom of the Paradise’" - including these nice bits from Paul Williams:

I had become friends with Liza Minelli. Liza was going up to Harrah’s in Lake Tahoe to play Harrah’s for a month. And she said “I want you to open for me.” I’m doing two shows a night with nothing to do during the day and I’m writing the songs. I had my road band with me. And my road band is the one that played on the Phantom soundtrack, on Bugsy Malone. We became so close that I’d walk in and start singing something and they’re playing chords behind me. And I could walk in and go “Okay, we’re doing a Beach Boys thing. Bum-ba-ba-da-bum… Upholstery.” And all of a sudden, it’s sounding like a Beach Boys record.Because we were fans of the music that we were satirizing – certainly all of us knew it well enough to recreate it. I had never written anything like “Somebody Super Like You” or “Life at Last”. But I just became a member of a rock and roll band. I became a member of a metal glam band. And the script is the bible. And the script was very fluid and it was developing along the way, and I just got caught up in the vibe that is Brian De Palma. Something happened and it came out of me musically.

It was so much fun, as you can imagine. And Brian seemed to embrace this total, very uncharacteristic for him sentimental side. I remember putting this little piano thing in when Bill is dying. And Brian said “Oh my god. There won’t be a dry eye in the house.” And my side of it is “And let’s show a really good closeup of the face in the record press.” It’s like we traded personalities during the shoot.

There's another very nice tidbit from Paul Williams included in Laurent Bouzereau's latest book, The De Palma Decade:

Larry Pizer was the great cinematographer on the film, but Ronnie Taylor, who became an Academy Award-winning DP with Gandhi [1982], was the camera operator. He did that amazing handheld shot from the point of view of the Phantom, which starts outside the Paradise, goes backstage, up the stairs, and ends inside the wardrobe storage room where he selects his leather outfit, finds the one-eyed mask, and puts it on, literally, over the lens of the camera. This was done in one shot before the Steadicam [existed], and it is spectacular.

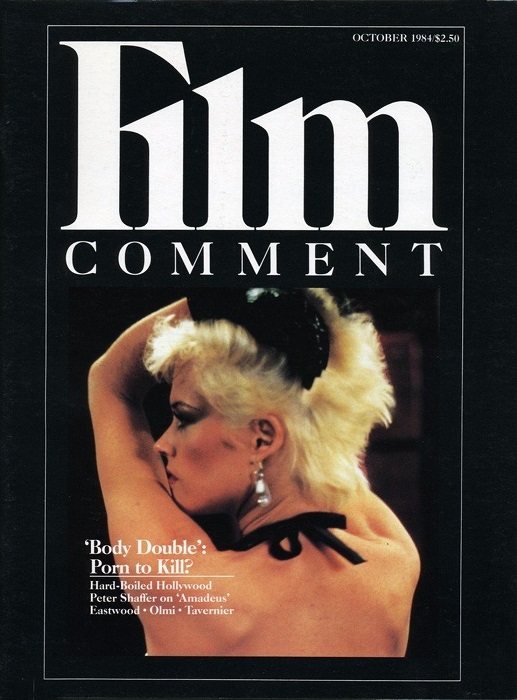

As in Sisters (1972), Obsession (1976), and Dressed to Kill, De Palma draws on Hitchcock’s style and themes in order to create sly pyrotechnics that are entirely his own. If the initial scenes of Jake stalking Gloria nod towards Vertigo (1958), they soon build into an extraordinarily well-choreographed ballet once they reach the Rodeo Collection mall. Largely free of dialogue, and almost entirely carried by movement and Pino Donaggio’s opulent score, it’s a jaw-dropping tour-de-force, playing with geography and perspective. Stephen H. Burum’s stunning camerawork moves up and down and left to right, using every inch of the space while tightly controlling what it wants us to see.Sometimes we know more than the characters (as when we see the ‘Indian’ or the security guard sneak by), and sometimes we’re left as shocked as Jake by a sudden reveal. It’s an astoundingly involving sequence, particularly considering that nothing especially dramatic happens. Admittedly, it draws on Hitchcock’s techniques, but even he was rarely so deliciously audacious in scale, nor so fearless in displaying his own mischievous sleight of hand.

Most controversially, the mall scene and indeed the first half of the film revolve around a man spying on an attractive, troubled woman. Rather than play the scenes subtly, De Palma amps up the slick eroticism to cartoonish levels, as if determined to enrage those who’d considered Dressed To Kill too leering and sexist. Of course, the most implausible and overtly sexualized moments are when Jake watches ‘Gloria’ dance at her window, and these are later revealed not to be her at all. However, it’s left for the viewer to decide whether these deceptive performances by adult actress Holly Body (Melanie Griffith) are a comment on the ludicrousness of straight male fantasies, or whether they’re simply a further example of the unrepentant male gaze in cinema.

Certainly, while she has a broadly similar character arc, Shelton’s Gloria remains passive and underdeveloped compared to Angie Dickinson’s Kate in Dressed to Kill, and the scene in which she kisses Jake despite knowing he’s been following her is ridiculously unlikely (if typically stylish). Likewise, although De Palma has always denied it was intentional, Gloria’s death by drill at the hands of her estranged husband has distinctly phallic overtones, as if designed to enrage feminist critics.

Yet judging these moments in isolation overlooks their context and the deliberate contradictions that run throughout the film. If Gloria’s murder is both horrifying and exploitative (a dichotomy at the heart of all horror cinema), her killer is never portrayed as anything but repugnant. Sam Bouchard (Gregg Henry) exudes arrogance, full of untrustworthy bonhomie and casual misogyny as he ensnares the meek Jake in his schemes. His contempt for others is made chillingly clear by the shot of him standing over Gloria’s body, hands on the drill and foot on her throat, his ‘Indian’ disguise adding blithe racism to his repulsively entitled characteristics.

Further, to suggest that the murder fits with the perceived slasher trope of “punishing” sexually active women is to overlook who replaces the deceased as the new female lead. Like Liz (Nancy Allen) taking Kate’s narrative place in Dressed to Kill, the second half of Body Double belongs to Holly Body—an assertive, strong, and sexually uninhibited woman rather than the traditional virginal ‘good’ girl.

While De Palma plays with puritanical audience expectations, he seems to delight in confounding them. Whether the role of a forthright adult film star is progressive or just more male fantasy is debatable, but it certainly suggests that the director’s world is more complex than the conservative standard attributed to certain slashers. (The fact that he had already spoofed the genre at the start of Blow Out and appears to reference Amy Jones’ 1982 The Slumber Party Massacre with Sam’s choice of murder weapon further implies a playful awareness of the pleasures and limitations of the form.)

Perhaps the most provocative and confrontational aspect of Body Double is the way its games implicate us as viewers. De Palma knows that voyeurism is the essence of cinema, and the more transgressive the sights, the better. Like Jake spying on Gloria/Holly from the dark of his apartment, we know we should look away—but we can’t. It’s no accident that the prominent line of dialogue during the porno movie shoot within the film is “I like to watch”. Nor is it a coincidence that just before showing Jake the telescope that sets the plot in motion, Sam proposes a toast “to Hollywood”.

Indeed, the film’s gleefully tawdry thriller plot is arguably a trojan horse disguising a caustically witty commentary on the dreams and disappointments of Tinsel Town. It emphasizes the tedium and hard work of trying to make it: enduring hostile auditions, attending pretentious acting classes, and surviving the trials and tribulations of cheap B movies like the opening sequence’s Vampire’s Kiss. The film is littered with L.A. landmarks, from the Capitol Records Building and Tail O’ The Pup to the Chemosphere that serves as the location for Jake’s adopted home. By locating its violent climax at the L.A. Aqueduct Cascades, it places the sex, danger, and illusion of the plot on an equal footing with the water supply, as though all these elements are essential to the city.

But the sexual content with which De Palma packed Body Double is potent. He chose Melanie Griffith, then in her mid-twenties, to play porn star Holly Body. He’d met the daughter of Hitchcock star Tippi Hedren while making Scarface; she was the girlfriend of actor Steven Bauer, who plays Tony Montana’s lieutenant Manny in the movie. And Double contains a funny Scarface in-joke. Bauer appears here as one of Holly’s sexual partners in a scene from Holly Does Hollywood, one of Double’s porno-films-within-a-film. He comes into a small room where Holly sits, prepared to do her oral stuff, and is interrupted by a voice on his walkie-talkie saying “Manny, where the hell are you? We need you on set.”Body Double’s plot is a gloss on Hitchcock’s Rear Window, with some morbid femme obsession from Vertigo tempered in. During the height of his career De Palma got a lot of critical smack for his lifts from Hitchcock, but that was unfair. He didn’t take cues from Hitchcock because he was bereft of his own ideas; he did because he knew that the stuff could be constructively and pertinently updated in explicit contemporary terms. In crude terms, it meant he got show things that Hitchcock never could. But it also meant he could make the subtexts in Hitchcock bubble up to a mordant surface.

Heights are the hero’s fear in Vertigo; in Body Double Jake Scully is claustrophobic, which makes his time in a coffin as a glitter-rock vampire (shades of De Palma’s early ‘70s quasi-glam musical Phantom of the Paradise!) in the movie’s opening less than tolerable. He freaks out, gets fired from the schlock movie he’s acting in, and now he’s got an impediment that he has to conquer in his hero’s journey. This journey finds him accepting the generosity of a fellow actor, who sets him up in a crazy ultra-modern UFO-like house in the Hollywood hills; across the way is another house with large horizontal windows and loosely space vertical blinds, and in that house a very scantily clad young woman dances with a remarkable lack of inhibition. Nice for Scully that the joint where he’s housesitting has a top-brand telescope. It’s almost too convenient, right?

And here, for all the rampant sex, corrosive inside-moviemaking humor, and general impertinent attitude, is where we hit the Problematic, in what, it happens, is the movie’s only murder. Given its grisliness, one is all Body Double needs.

You could reasonably make the claim that over the course of the film Paul Williams predicted numerous trends in the music industry. With Somebody Super Like You, he seemed to pre-empt the theatre of bands like Kiss and Goth Rock. Throughout the film, Swan’s group The Juicy Fruits pop up in a variety of guises, performing variations of the Phantom’s work. For this song the group are all dressed as somnambulist Cesare from The Cabinet Of Doctor Caligari, with a stage set that recreates the German expressionist mise en scene. Now called The Undead, this Frankenstein-inspired anthem celebrates an ideal man, assembled from various body parts, creating a campy, terrifying experience. The bone-chilling screams from singer Harold Oblong are incredible, as are his distinctive vocals, full of little tics – “Somebody sssssuper like you!”Incidentally, this was the highest charting song from the soundtrack. It went platinum, but curiously, only in Winnipeg!

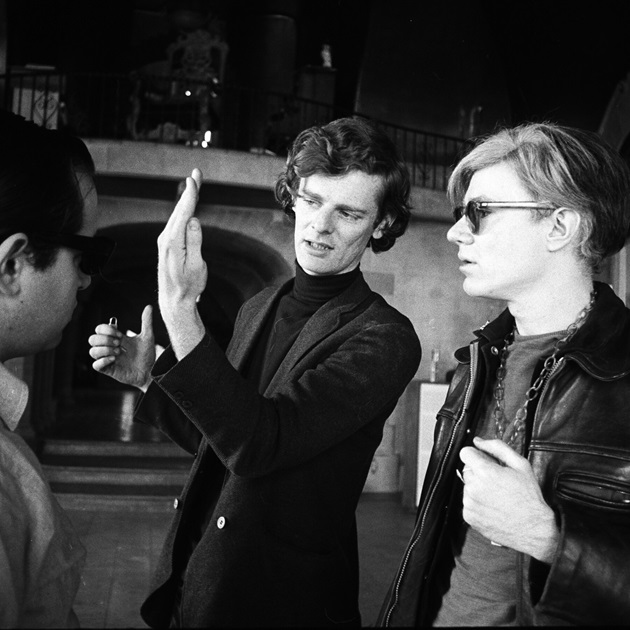

Mr. Morrissey was born on Feb. 23, 1938, in Manhattan to Joseph and Eleanor Morrissey, and grew up in Yonkers, N.Y. He attended Roman Catholic schools and studied English at Fordham University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1955 and began making 16-millimeter silent films. His first effort, a one-reeler, showed a priest saying Mass on a cliff top and then throwing his altar boy over the edge.Despite the subject, Mr. Morrissey was not rebelling against the church. He enjoyed perplexing interviewers by fully endorsing his Jesuit education, heaping scorn on liberals and denouncing sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll even as he presented, without comment, scenes of shocking degradation on film.

“With us, everything is acceptance,” he once said of his collaborations with Warhol. “Nothing is critical. Everything is amoral. People can be whatever they are, and we record it on film.”

After serving in the Army, Mr. Morrissey ran, and lived in, an underground cinema in the East Village, where he showed his own films and those of others, including “Icarus,” an early effort by Brian De Palma. Mr. Morrissey later took pains to explain that he was not part of the experimental-film movement. With his interest in stars and narrative, he was, as he liked to put it, “independent of the independents.”

Mr. Morrissey was introduced to Warhol in 1965 by the poet and filmmaker Gerard Malanga at a film screening, and the Factory phase of Mr. Morrissey’s career began. At the time, Warhol was making experimental films at the commercial loft on East 47th Street known as the Factory. The titles capture their static, impassive aesthetic: “Hair Cut No. 1,” “Shoulder,” “Couch.” The camera stared, unblinking, and whatever happened, happened — or didn’t.

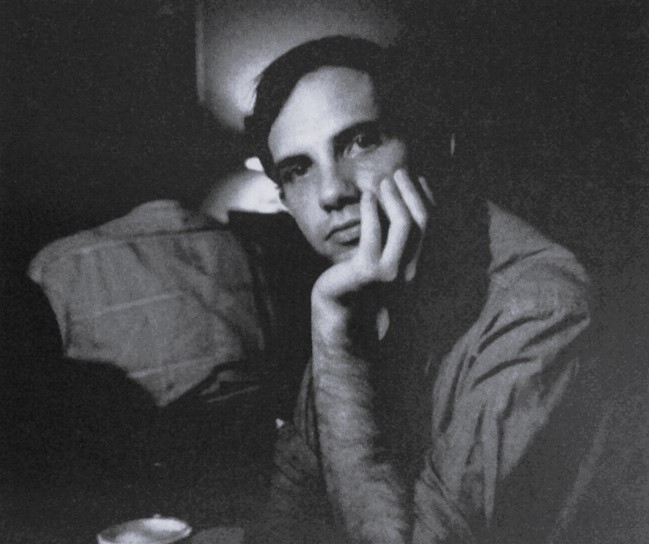

Early in 1958, prior to leaving home in Philadelphia for Columbia University, De Palma had been working to document his father's infidelity by recording his phone calls, following him to work and snapping photos outside his father's office window. According to the book Shock Value by Jason Zinoman, De Palma told one friend that year that the photos were his "first film." In 1970, De Palma mentioned his "background in photography" to Joseph Gelmis (for Gelmis' book The Film Director As Superstar) as he explained how he ended up directing his first short film, Icarus, in 1960:

I started making movies when I was at Columbia University as a sophomore. I was with the Columbia Players, and I had a background in photography. I was obsessed with the idea of directing the Players. But they wouldn't let undergraduates direct them, so I was frustrated. I figured I'd go out and direct movies instead.

Laurent Bouzereau (in The De Palma Cut) states that De Palma "created a film association between Columbia University and Sarah Lawrence College. The famous stage director Wilford Leach, who conducted a theater class at Sarah Lawrence, was immediately impressed by the young man's energy and interest in filmmaking. Leach soon became De Palma's mentor. According to De Palma, Leach was one of the very few people who ever understood him." Bouzereau goes into further detail about the making of Icarus:

In 1960, Brian De Palma made Icarus, which he today considers a pretentious film, though he admits that it encouraged him to learn more. At first, De Palma was only supposed to be the cameraman on Icarus, but the director left the set after many arguments with De Palma, who was already trying to impose his own visual ideas, regardless of his position. Luckily, De Palma was then offered the opportunity to finish the film himself.