EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: BRIAN DE PALMA

TALKING ABOUT 'PASSION', WITH SPOILERS Brian De Palma

Brian De Palma deserves nothing less than an A+ for his tireless promotion of his new movie

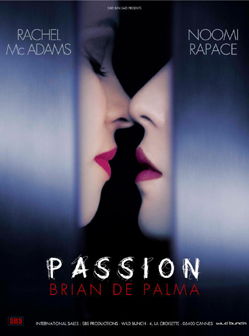

Passion. The film premiered a year ago at the

Venice Film Festival, which he attended with

Pino Donaggio and

Noomi Rapace. From there, the film was screened at the

Toronto International Film Festival, where

Rachel McAdams joined De Palma to answer questions from the audience. Then on to the

New York Film Festival, where,

despite a gaff with the digital projection on the night of its U.S. premiere,

Passion had already been well-received at a press screening earlier in the week. At that festival,

De Palma appeared on stage with his filmmaker friend Noah Baumbach, where each one discussed their latest movies. During each of these festivals, De Palma participated in countless interviews with various media outlets, from trade publications, to web blogs, and everything else in between.

Earlier this year, De Palma was doing more interviews with European outlets where Passion opened between February and May. He then spent much of the late spring and early summer giving interviews for the film’s pending releases in the U.K. (where Passion was released on DVD earlier this month), the U.S. (where it opened in theaters yesterday), and Canada (where it will open in September).

Anyone who has been reading this site regularly knows that we’ve been doing our best to keep up with all the interviews, which are of course full of repeat questions and answers, give or take some minor variations. But each one usually has some other interesting piece (or pieces) of information that can result from the interviewer asking something they are particularly curious about, or else De Palma tries to “put a new twist” on the same old question. In any case, what this all makes entirely clear is that De Palma is proud of Passion, and is doing his best to ensure its release is as successful as can be.

And he should be proud of it. Passion, a remake of Alain Corneau’s Crime d’amour, is De Palma’s most fun, relentless wind-up toy of a movie since Raising Cain, with a killer performance by Rachel McAdams. At its center is a magnificent split screen ballet sequence that compels and frightens simultaneously, leading us deeper into a psychosexual surrealism that is informed by the advertising world in which its characters are engulfed. Within that world, Isabelle, played by Noomi Rapace, is a focused, hard-working creative visionary who wakes up with ideas straight from her subconscious, a semi-surrogate for De Palma himself.

I spoke with De Palma by phone on the last day in July, just as he was getting ready to take a vacation prior to Passion’s U.S. release. And then he was right back at it August 19, discussing Passion on stage at the Lincoln Center and doing even more interviews leading up to the release date. In any case, in the interview below I think you’ll find that we covered at least a little bit of ground that was previously untouched.

This interview contains SPOILERS about Passion.

-------------------------------------------------GB: In this movie, perhaps more than any of your others, the audience’s sympathies seem to be aligned with a killer’s, although we kind of don’t know it until the end. By way of contrast, it kind of made me think of Snake Eyes, where you reveal the true villain about halfway through the picture. What motivates that kind of decision? BDP: Well, if you’ve seen the original movie, you know they reveal the killer halfway through. And I thought that didn’t make for a very interesting second half of the movie, where you’re basically showing the whole planted clues or that they’re not connected to Isabelle, when in fact, they’re set up to make you think it’s Isabelle, but upon closer examination, you find out that they’re false clues. Which of course requires a lot of flashbacks, and a kind of tedious summing up of what actually happened. I thought it was better to make the audience think that Isabelle was all doped up and didn’t exactly know what happened and what didn’t happen. Try to keep the audience as confused as she seemed to be right up until the end of the movie.

GB: Passion kind of has a unique structure too for you, I think, in that for the first half of it, there seems to be two protagonists. We’re not just following Bucky Bleichert, or Jake Scully, or Courtland from Obsession. You kind of employ parallel editing and give each of the two main characters equal screen time apart from each other. Were you trying to angle the audience’s sympathy toward one or the other in the first half?

BDP: I don’t think so. I more or less followed the original movie in terms of the conflict that they were having with each other, basically until she goes home and takes all the pills and, you know, it becomes the surreal dream section. But that’s basically the way the original movie was laid out, and it seemed quite sound to me.

GB: Did you use storyboards for Passion?

BDP: Yes. I took a long time to lay out…you know, I was in Paris for two years. It took me a long time to get the movie cast, so I had a tremendous amount of time to work out every shot in the movie. We had a very industrious production designer [Cornelia Ott] who literally went to every location and photographed every angle I had in my storyboards, which I would then put into my storyboards. As soon as she gave me a photograph, it went into my drawing.

GB: And also for Passion, you worked with an experienced editor [François Gédigier], but one you hadn’t worked with before. Did you learn any new tricks from that kind of collaboration?

BDP: Not really. That was kind of a delightful thing, because I was, you know, a little apprehensive about working with a new editor. I’ve worked with the same two or three editors for decades. But this was somebody suggested by Saïd Ben Saïd, the producer, and I said, "Okay, I’ll give it a try, but, you know, if it doesn’t work out, we have to bring in one of my old editors." But in fact, it worked quite well. We literally had the movie cut by the time we finished shooting. We literally, when we went back to Paris, we were just waiting for the last two days of shooting in order to, you know, be able to work that in.

GB: How did you find the dancers for the ballet?

BDP: Well, that’s a whole elaborate process you have to go through. The Jerome Robbins Trust controls that ballet completely. So if you want to use it, you have to use their costumes. The costumes are always the same. The way the dancer’s hair is, is always the same, which means the ballerina has to wear her hair down. The set is exactly the same. You have to create the set according to the original one. And needless to say, the choreography is exactly the same. The only thing I changed was, instead of having them looking at a mirror, which is what the dancers are supposed to be doing [in the film] when they look straight in the camera, I had them look straight in the camera. And the Jerome Robbins Trust also approves the dancers. Fortunately, we had Polina [Semionova], who is the lead dancer in the Staatsballet in Berlin, and they approved her, but it took a while before they approved a male dancer.

GB: Wow. That’s a really great sequence. I think it works really great in the film.

BDP: Yeah, it looks beautiful. I quite enjoyed shooting it, and I think Polina is just magical to watch.

GB: Yes, I agree. Did you have any other concerns or challenges about shooting the ballet itself?

BDP: No, shooting ballet is pretty straightforward. I mean, we had to shoot it, supposedly, all from Isabelle’s point of view. And you more or less always shoot ballet, you know, shoot it from head to foot. Of course, you cut it closer for some of the emotional reactions of the dancers. But if you look at ballet coverage, they literally just shoot it from head to foot. You have to see the whole dancer’s body. And the only problem was, I would think, that I had to do it so many times that they really got exhausted.

GB: During that split screen sequence, Noomi’s eyes kind of take over the screen at one point, almost as if she’s in two spaces at once. On a second and multiple viewings, we’re pretty sure she’s still dreaming at this point. We don’t necessarily know it on the first viewing. I tend to surmise that perhaps, like in the original movie, Isabelle sat through the ballet one night on her own without letting her assistant know. Is that perhaps why the ballet plays out in her dream? Or is that getting too far off...?

BDP: No no no no. The intention was always to shoot those tight close-ups to make the audience think she is at the ballet, when in fact, later in the movie, I show where that close-up comes from, and I pull back and show that she’s underneath the scaffolding. It’s a trick, basically. I mean, to put her on the left side of the screen, while the murder’s going on on the right, so the audience would never think she could have possibly done it.

GB: Yes, okay. In this movie, you sort of continue the experiment of Redacted, where you incorporated current forms of media and technology within a more traditional narrative. Had you been planning to incorporate similar elements in your John Edwards-inspired political campaign thriller?

BDP: Yeah, but those scripts and those ideas were all completely digital reality, whether they were, you know, reality television shows, or stuff you find on the web. They’re all constructed, like Redacted, over supposedly found footage. This, because I decided to use this commercial for the smart phone, I decided to make it a whole element in the movie. And these, you know, kinds of things that grow out of smart phones, besides texting. One of those is, of course, the commercial, which I basically copied from a real commercial on the internet, of a girl sticking the phone in the back pocket of her girlfriend and walking around, having people stare at her ass. And which was in fact posted on the internet and went viral, and was in fact made by two advertising executives. So I basically copied that commercial completely. And then I added the use of the phone where he’s making the sex tape, and he is f---ing her in the room.

BDP: Yeah, but those scripts and those ideas were all completely digital reality, whether they were, you know, reality television shows, or stuff you find on the web. They’re all constructed, like Redacted, over supposedly found footage. This, because I decided to use this commercial for the smart phone, I decided to make it a whole element in the movie. And these, you know, kinds of things that grow out of smart phones, besides texting. One of those is, of course, the commercial, which I basically copied from a real commercial on the internet, of a girl sticking the phone in the back pocket of her girlfriend and walking around, having people stare at her ass. And which was in fact posted on the internet and went viral, and was in fact made by two advertising executives. So I basically copied that commercial completely. And then I added the use of the phone where he’s making the sex tape, and he is f---ing her in the room.

GB: The nightmare sequence at the end I think is one of your best. I read that you came up with the idea for the final shot at the last minute. Were you originally going to end without any shot of Isabelle waking up?

BDP: Well, I knew I was going to end up with Isabelle waking up, but, to give it that last twist, to leave that body on the floor, that sort of came to me while I was shooting the sequence. You know, did she strangle her in her sleep? She got away with one murder, but what is she going to do about this one? I mean, basically, you leave all these questions with the audience.

GB: Yeah, and it kind of makes them laugh when the words “The End” come up.

BDP: Yeah. Her problems are hardly over.

GB: Right. So Isabelle is obviously expecting Dirk to show up at Christine’s party. But when he shows up drunk and crashes his car, it seems safe to say that she becomes a bit like Cain from Raising Cain, improvising perhaps other ways to set up the crime with what’s available. Would you agree maybe there’s a bit of improvisation, even though she’s sort of planned the perfect murder?

BDP: Obviously, I’m trying to create as many suspects that aren’t Isabelle as possible, you know, whether it’s Dani, or the rejected boyfriend, mainly pointing to the rejected boyfriend, so I had to get him to the party. And getting on the premises right around the time of the murder, you know, so he’s implicated, and also have the car there, so that Isabelle could plant the scarf in it.

GB: And she pretty much knew he would be there?

BDP: Well, there could be a certain amount of improvisation. I don’t think she necessarily had to know he was going to be there. But when she saw him, or heard him yelling, you know, “Christiiine! Christiiine!” As in all great murder plots where the best ones are always when you use something that happens in the moment that nobody ever predicts, she used the fact that the car was there and he was stumbling around to really close the loop on who was the primary suspect.

GB: Okay. And in Isabelle’s confession scene, there seem to be echoes of Amanda Knox when she says “I must have done it.” But of course, she feels a certain amount of pressure to confess, in order to go along with her own plan, because they’re processing DNA evidence, and she can’t wait for that to go through…

BDP: Well again, that’s from the original movie. You know, where she says, “I did it. I must have done it.” Which is a kind of a leap of credibility, but she’s trying to, and I tried to play it up, that she was so confused that she’s not exactly sure what she did. But in fact, she knows exactly what she’s doing.

GB: Do you still maintain an active writing routine these days?

BDP: Yeah, you know, I’m always working on something. The ideas I get, I’ll write 20 or 30 or 40 pages. And sometimes they work into a whole script. Sometimes they’re just ideas that I work out, and ultimately get used in something. I mean, the ballet thing is something I’ve been thinking about for years, and appeared in a couple of scripts.

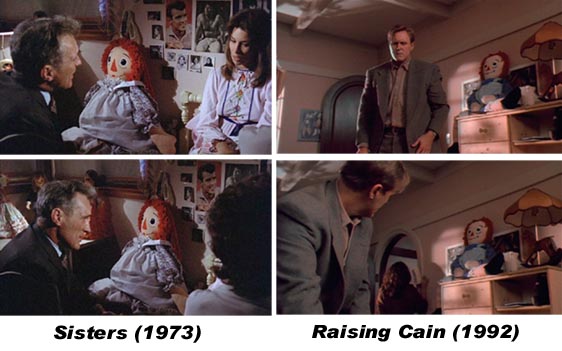

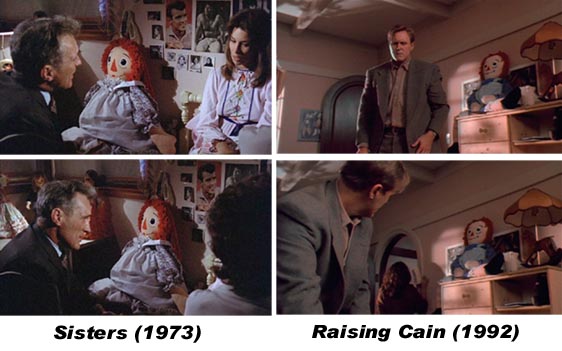

GB: That’s cool. Some of us have noticed a recurrence of Raggedy Ann dolls within girls’ bedrooms in some of your older movies. Is there any pointed significance to this that you know of?

BDP: No. That’s, you know, it’s a Raggedy Ann doll, it’s my subconscious at work. It’s not like I said, “Oh! Let’s put the Raggedy Ann doll in there.”

BDP: Yeah, but those scripts and those ideas were all completely digital reality, whether they were, you know, reality television shows, or stuff you find on the web. They’re all constructed, like Redacted, over supposedly found footage. This, because I decided to use this commercial for the smart phone, I decided to make it a whole element in the movie. And these, you know, kinds of things that grow out of smart phones, besides texting. One of those is, of course, the commercial, which I basically copied from a real commercial on the internet, of a girl sticking the phone in the back pocket of her girlfriend and walking around, having people stare at her ass. And which was in fact posted on the internet and went viral, and was in fact made by two advertising executives. So I basically copied that commercial completely. And then I added the use of the phone where he’s making the sex tape, and he is f---ing her in the room.

BDP: Yeah, but those scripts and those ideas were all completely digital reality, whether they were, you know, reality television shows, or stuff you find on the web. They’re all constructed, like Redacted, over supposedly found footage. This, because I decided to use this commercial for the smart phone, I decided to make it a whole element in the movie. And these, you know, kinds of things that grow out of smart phones, besides texting. One of those is, of course, the commercial, which I basically copied from a real commercial on the internet, of a girl sticking the phone in the back pocket of her girlfriend and walking around, having people stare at her ass. And which was in fact posted on the internet and went viral, and was in fact made by two advertising executives. So I basically copied that commercial completely. And then I added the use of the phone where he’s making the sex tape, and he is f---ing her in the room.

Karoline Herfurth has been acting in front of the camera since she was ten years old, when she appeared in the German television movie Holiday Beyond The Moon. After playing teenagers in several feature films, she gained international recognition for her role as "The Plum Girl," the initial victim in Tom Tykwer's Perfume: The Story Of A Murderer, which starred Dustin Hoffman, Ben Whishaw, and Alan Rickman. In 2008, she appeared with Kate Winslet and Ralph Fiennes in Stephen Daldry's Oscar-nominated adaptation of Bernhard Schlink's The Reader. That same year, Herfurth played dance student Lilli Richter in Caroline Links' A Year In Winter, a role which won her the Bavarian Film Award for best young actress. In 2010, Herfurth starred in We Are The Night, as a young woman drawn into a clan of female vampires.

Karoline Herfurth has been acting in front of the camera since she was ten years old, when she appeared in the German television movie Holiday Beyond The Moon. After playing teenagers in several feature films, she gained international recognition for her role as "The Plum Girl," the initial victim in Tom Tykwer's Perfume: The Story Of A Murderer, which starred Dustin Hoffman, Ben Whishaw, and Alan Rickman. In 2008, she appeared with Kate Winslet and Ralph Fiennes in Stephen Daldry's Oscar-nominated adaptation of Bernhard Schlink's The Reader. That same year, Herfurth played dance student Lilli Richter in Caroline Links' A Year In Winter, a role which won her the Bavarian Film Award for best young actress. In 2010, Herfurth starred in We Are The Night, as a young woman drawn into a clan of female vampires.

Reviews of Passion are proliferating-- here are some samples:

Reviews of Passion are proliferating-- here are some samples: At last week's

At last week's