MATT ZOLLER SEITZ - 'PHANTOM' 50TH ARTICLE FOR D MAGAZINE

TALKED TO DE PALMA, WILLIAMS, HARPER, HIRSCH, ARI KAHAN, STEPHANIE ZACHAREK

Such an exciting time, with

Body Double turning 40 and

Phantom Of The Paradise turning 50.

Matt Zoller Seitz has written an article about

Phantom Of The Paradise for the October issue of

D Magazine. And Seitz drops in a reference to De Palma's

Home Movies in the opening paragraph.

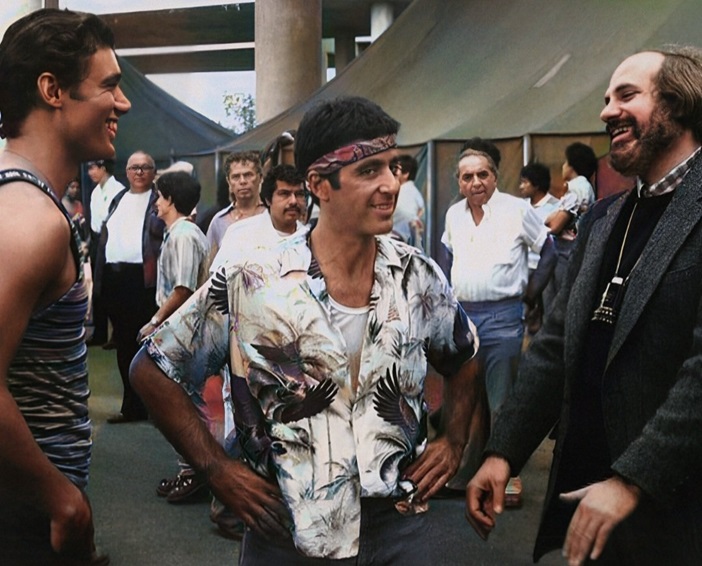

"Of all the movies shot in Dallas," Seitz begins, "Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise is the most singularly odd. Considering the existence of RoboCop, JFK, Logan’s Run, Office Space, and Mars Needs Women, that may seem like a bold statement. But if you’ve seen Phantom—a rock-and-roll black comedy horror riff on The Phantom of the Opera, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and the legend of Faust shot mostly in the 1,704-seat Majestic Theatre—you’ll nod in agreement. (Those who know, know.) Then you’ll keep nodding and nodding until you’re bobbing your head in time to one of the incandescent songs burned into your memory by Paul Williams, Phantom’s songwriter and costar, whose performance as the film’s villain, Swan—a record producer who signed a pact with Satan, steals songs from a brilliant but unknown composer named Winslow (William Finley), and ruins the poor man’s life—represents the only instance in 1970s American cinema in which a 5-foot-2 actor can be said to loom."

It's a great article, and you'll want to read the entire thing, of course - but here is a brief excerpt:

In an act of programming chutzpah worthy of Winslow, Phantom of the Paradise will be screened October 26 at the Majestic Theatre with Paul Williams in attendance. That means viewers will have the unique opportunity to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the film in the presence of the actor who plays the bad guy and watch the hero garrote, bludgeon, crush, stab, and electrocute his enemies on a 30-foot-high screen in the same venue where the movie was shot. Phantom was born in a moment of Winslow-like righteousness. Sometime in 1969, De Palma was riding in an elevator when he heard a bland Muzak arrangement of the Beatles song “A Day in the Life.” “I thought, ‘Boy, they sure managed to take this really original song and turn it into pap!’ ” he says.

The incident sparked his imagination. He had recently been in England shooting footage for a documentary about rock-and-roll artists, including The Who, The Animals, and The Rolling Stones. “We were shooting them in all the original clubs where they’d played,” De Palma says, “and the producer [of the documentary] also knew Bob Dylan, so I’d spent some long evenings up where Dylan was, so I’d gotten to learn a bit about the music industry.”

By that point, De Palma had also spent a few years in the film business, which had its own parasites and predators. “I figured out pretty clearly what I wanted to do,” he says: a rock-and-roll horror film with original songs. Phantom’s antagonists would be the innocent and idealistic composer Winslow, whose Faustian rock-and-roll tragedy becomes a meta-commentary on the movie you’re watching, and Swan, who leeches Winslow’s gifts to ensure the success of the new concert hall he’s opening, then strips the composer of his art, his dignity, his face, his voice, his soul, and even his ability to die. (The contract signed in blood by Winslow specifies that he can’t die until Swan does; you can probably guess what the loophole is.)

FINLEY'S IDEA, CIRCA 1964 - A MOVIE ABOUT MODS & ROCKERS WITHIN A THEN-BURGEONING SCENE IN LONDONThe documentary De Palma is talking about was to be titled Mod. Robert Fiore had collaborated with Brian De Palma on several films in the 1960s. Along with Bruce Rubin, Fiore did a little of everything in the De Palma camp. He was the sound recordist on Murder A La Mod (a clip from which ended up playing on a TV in a scene from Blow Out years later). Fiore was the cinematographer on Greetings, and shortly after, co-filmed the split-screen documentary of Richard Schechner's Dionysus In '69 with De Palma and Rubin (the latter recorded the film's sound). Fiore was the cinematographer on To Bridge This Gap, a documentary by Ken Burrows and De Palma, which was edited by Rubin.

There was one other project, a lost documentary from earlier in the 1960s that was to be titled Mod. Fiore, De Palma, Rubin, and William Finley had all shot footage in England. It was Finley's idea, circa 1964, a movie about mods and rockers within a then-burgeoning scene in London. In Justin Humphreys' book, Interviews Too Shocking To Print, Rubin explains that Finley's father had died and left him money, which he was going to use to finance the film. "And I was amazed at the audacity of somebody taking money that they had inherited and immediately spending it on making a movie," Rubin tells Humphreys. "But he was so enthralled by what was going on in London - the whole new music scene and he wanted to document it - to get it on film before it went away because this was the moment of birth for that whole [movement]. I mean, The Beatles were just coming out, and The Stones, and everybody - The Animals, Herman's Hermits, on and on."

After arriving in London ("there was a whole group of us," Rubin says in the book), Finley asked if Rubin would go to France with De Palma to pick up a light Eclaire sound camera, mentioning that he also needed another person to work on the film. Rubin had known Fiore from film school, and De Palma had known Fiore, as well. Fiore happened to be on a Fulbright grant in Paris, "and so he agreed to come back from Paris with us to work on the film," says Rubin, adding that they all had "an incredible two days" in Paris before heading back to London, where they worked on the film for two weeks, "through Christmas and New Year's."

Rubin continues in Humphreys' book:

"Bob Fiore and I went to Birmingham, I think... We drove up there and we went to the Beatles' Cavern (The Cavern Club in Liverpool] and there was a group showing there that night called Herman's Hermits. We got permission - I had a card that said I was from ABC News. I don't know how I got it but people thought that's who I was. They made a lot of things available. We went in and I had enough film to shoot one act of the concert. And it was Herman's Hermits, so I got the camera and Bob Fiore was my sound man at that point. I shot this amazing, exciting number using every element of the zoom lens. It was really very, early '60s exciting experimental cinema. I really shot a great roll of film of Herman's Hermits. "And then, right after it was done, and we were out of film, the announcer onstage says, 'And, now, everybody - here's Herman!' I had shot the whole backup group without their leader, so I had wasted every bit of film of some of the most brilliant filmmaking of all-time.

"We were very ragtag as a group and we did what we could do. We did shoot some stuff of a group called The Who in a room in a hotel but nobody had ever heard of them, really, but people were saying, 'This is going to be a big group.' It was a small hotel performing area in a restaurant, like. I did shoot some of their performance."

Much of the film shot in England was impounded by Customs agents at the airport. Finley did not want to pay Customs taxes, so they had tried, unsuccessfully, to pass the rolls of film off as bits of tourist footage shot by each individual. On top of all that, the agents ran the film rolls through x-rays, likely destroying much of the images. Rubin, who was paid by Finley to transcribe the sound tapes they all recorded, says that Finley did manage to get some of the film back at some point, but doesn't know much more than that.

Mod remains, for now, a lost film.