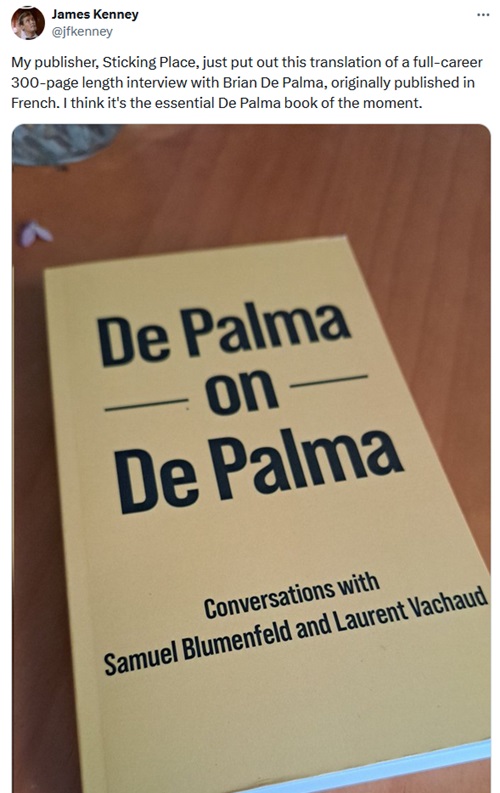

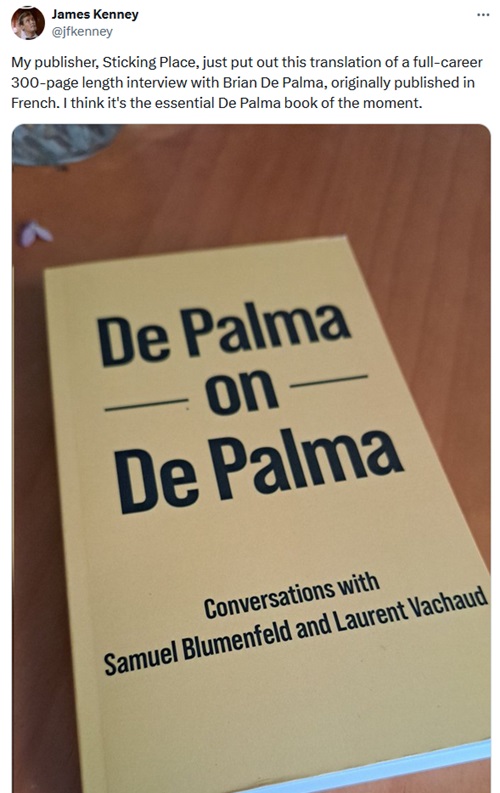

THE STICKING PLACE LINK TAKES YOU TO AMAZON TO PURCHASE

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | October 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

So much of Carrie now looks, 48 years on, unsubtle to say the least – and yet De Palma is a master of making that lack of subtlety work cinematically. The frankly outrageous soft-porn aesthetic of the initial girls’ locker room scene gives us Spacek almost languorously soaping herself in the shower, in a way that is madly inconsistent with her character. And yet without that absurdly provocative sequence, the “period” moment wouldn’t have been so transgressive, so nasty, so tactless. This is crass, this is the male gaze, sure – and yet it is subverted by its casually explicit violence and vulnerability. It’s impossible to feel anything other than genuine protective concern for a female character who is later to show that she doesn’t need anyone’s protection.And that staggering, drawn-out prom sequence, in which Carrie evolves from ugly duckling to swan to something else entirely – its meaning and atmosphere changes on a subsequent viewing. The first time you watch it, the denouement is a shock, despite the fact that in previous scenes you’ve seen the nasty planning that has gone into it. But the second time, the scene is, end to end, an unbearable ordeal of pure evil: minute after minute goes by while Carrie progressively relaxes and begins to enjoy herself with the wonderful boy who’s taken her on this date. And then, when she unleashes her gonzo uproar of telekinetic rage, De Palma fragments the spectacle with a split-screen: a crazy death metal of carnage.

Carrie is about all the things it didn’t know it was about: internalised misogyny and self-hate, and the theatre of cruelty involved in high school popularity. It isn’t explicitly about school shootings and yet it shows you, like no other film I have ever seen, the horrifying wish-fulfilment ecstasy of such horrific acts. De Palma is the only director who could have done it.

Speaking to Noah Baumbach in the 2015 documentary about his career, De Palma recalls, “I had carte blanche to make this movie, and it was all great until they saw it.” “Body Double” was made in the fallout of financial failures and frustration, cashing in on the recent success of “Scarface” to make an impossible “how did this get made” miracle of a pervert cinema. After years of feeling chewed out by Hollywood, De Palma channeled the anti-establishment anger of his earlier political documentaries into a psychosexual autocritique of himself and his career, as well as a bracing satire of show business and the ghouls inside it. Or, as crime novelist Megan Abbott wrote, “His movies thus become conspicuous, gaudy spectacles of male anxiety and lust, orgies of panicked masculinity in the face of the powerful female.”“Body Double” is the ultimate expression of that theme. Over the last decade, De Palma had a rough run: “Carrie” was a hit, but the Travolta-starring “Blow Out” (a masterwork of paranoia) cost more than “Star Wars” and flopped. He’d just finished a fraught battle with the MPAA over the rating on “Scarface,” and was licking his wounds from a tough divorce with Nancy Allen, his creative muse since “Carrie.”

It was under that industry heat that “Body Double” was born, daring not only to remake one Hitchcock classic but two: a twisted double-bill of “Rear Window” and “Vertigo,” reconceptualized through the pop-kitsch prism of MTV and the lubed backrooms of 1980s hardcore porn. Take the opening scene, with De Palma’s camera panning through an imitation graveyard, tilting into an underground coffin to reveal a bleach-blonde vampire, collared in the couture of S&M. He’s staring at the camera, at us, and we quickly realize something is wrong: a frozen fourth wall break, his fangs and crimson lipstick are unable to move. And then we hear, “Action, Jake. Jake, action…okay cut!” and see a bustling film set.

We were watching Jake Scully (Craig Wasson), a struggling actor. He, like “Scottie” in “Vertigo,” has a crippling psychological flaw. Instead of a dolly-zoomed fear of heights, Jake suffers from debilitating claustrophobia, and he discovers it while shooting the low-rent horror flick “Vampire’s Kiss,” risking ruin to his career. The director tells him to take the rest of the day off, a smiling backstab to fire Jake from the horror picture–the first sign of De Palma’s festering anger towards Hollywood.

This beginning sequence is a fever-dreamed meta-commentary not only on the rest of the movie but the nature of cine-artifice itself. It also recalls the opening of “Blow Out,” another De Palma picture that begins with a film within a film, both movies tricking us into the illusion we’re watching low-grade horror pictures, satirical jabs at the kind of movies De Palma was accused of making. More importantly, they show a sudden branching of one cinematic world penetrating another, an idea reinforced again and again through “Body Double.” This includes even the title card, first revealing a western horizon, only to be then exposed as a matte painting wheeled away into the studio backlot. Should this matte backdrop seem any less “real” because, diegetically, we were shown it was fake when it isn’t any more or less illusory and authentic than when we first saw it? The riddle of suspension of disbelief is a tricky thing, and “Body Double” is a feature-long play on the idea, driving into a climax that turns these tricks into entire setpieces and structural games.

He wrote: “I’ve only recently learned that the perception in the industry was that I snubbed the Oscars – that I didn’t attend the ceremony because I was nominated for The Godfather as a supporting actor and not as a leading man. That somehow I felt slighted because I thought I deserved to be nominated in the same category as Marlon.

“Can you imagine that was a rumour that exploded at the time, and I only found out about it recently, all these years later? It explains a lot of the distance I felt when I came out to Hollywood to visit and to work. It was appalling to learn it now, having missed all these opportunities to deny it, not even knowing that this is what people thought of me. “

The Academy would soon forgive Pacino, nominating him for Serpico, The Godfather Part II, Dog Day Afternoon, And Justice for All, Dick Tracy, Glengarry Glen Ross, Scent of a Woman – for which he won – and The Irishman.

However, Pacino thinks Scarface should be on that list. While promoting the memoir on the Today programme, the actor, who played Tony Montana in Brian De Palma’s 1983 film, said: “I would have liked to have even got nominated for that one.”

Scarface was a huge critical flop at the time of release, with Pacino writing in the memoir: “Sometimes an audience doesn’t know exactly what it’s seeing right away, and they need time to take it in and absorb it.”

He added: “Scarface got no attention from the Academy Awards. I cannot overstate the unbelievable job Brian De Palma did on Scarface, mapping the film and charging it with such dynamism and reach. He took it to the limit. Why he wasn’t honoured for it will forever make me wonder.”

"Scarface" - I just recently went to the Aero Theatre because they were having a showing of it there, and they wanted me to talk. So I talked a little - I was overwhelmed when I saw it. I hadn't seen it for years. And so when I went there and saw this film on this big screen and the people who - most of the people weren't even born when "Scarface" came out. You know, Brian De Palma wanted to make it like an opera. He says that's...SHAPIRO: Over the top, operatic. Yeah.

PACINO: Yeah. That was his intent, so that somehow - and the color in there and John Alonzo's cinematography. So it was quite a film.

This was De Palma’s Godard era, shortly before he pledged allegiance to Alfred Hitchcock. But as is the case with the director’s homages, however explicit, they still feel filtered through his singular sensibility. Despite its blackout sketch structure and improv comedy hijinks, Hi Mom! is unmistakably a Brian De Palma picture: endlessly self-reflexive, obsessed with ways of watching and being watched, always implicating the audience in the action with a wicked cackle. It’s basically the same story as Body Double, chronicling a young peeping Tom’s pet perversions while playfully reminding us that cinema itself is founded on similar predilections.Rubin’s obsession with capturing “a private moment” on camera has followed him home from Vietnam. He talks a cut-rate pornographer (the hilarious Allen Garfield) into financing his dream project. Rubin has rented a crummy tenement across the street from high-rise apartment building, and spends his days pointing a camera into the windows of his neighbors. The first in a career full of nods to Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Hi, Mom! takes Jimmy Stewart’s nosiness one step further as De Niro attempts to insert himself into the narrative. Rubin comes up with a convoluted means of seducing a single gal across the way (Jennifer Salt) and turning his own residence into a Rube Goldberg camera setup so that he can film himself having sex with her in her apartment.

Such an endeavor requires extremely precise timing, with a wrench thrown into the works when she’s hot to trot the moment he walks in. It’s odd that De Niro’s late-career pivot to comedy was greeted as such a surprise given the slapstick shenanigans of these early De Palma pictures. In Hi, Mom! he tries on a whole bunch of silly accents, making great hay out of a high-pitched affectation that Rubin seems to think connotes being “cultured.” (For years my friends and I tried to mimic the high dudgeon with which De Niro exclaims, “I’ll be damned!”)

The movie’s most notorious sequence comes when Rubin joins a radical African-American theater troupe, playing a police officer in a production called “Be Black Baby.” The avant-garde performance art piece lures members of the moneyed Manhattan elite downtown, where they’re painted in blackface and horrifically abused by the Black actors – who are all wearing whiteface makeup and screaming racist slurs. The theatregoers are robbed, beaten and sexually assaulted until a cop (De Niro) interrupts, refusing to believe any of the battered audience members and only listening to the actors wearing whiteface. The sicko punchline to the sequence finds these upper crust liberals all raving about the experience afterwards, discussing how much they’ve learned about oppression and now they really understand how it feels to be Black.

Hi, Mom! was out of official circulation for many years, and I remember a friend finally tracking down a VHS copy when we were in college. That night, we all stared at the screen in slackjawed awe at “Be Black Baby.” Watching it today, it’s still difficult to believe what you’re watching. The sequence is supposed to be part of a documentary on the film’s PBS parody, National Intellectual Television. (My favorite throwaway gag is that NIT’s sister radio station has a show called “Music To Write Checks By.”) But somewhere along the line, De Palma abandons the mockumentary gambit and plunges us directly into the dislocation and horror of what’s happening. By the time he pulls back for the punchline, the laughs can’t help but stick in your throat. It’s one of the most audacious things I’ve ever seen.

“To me, Carrie is timeless in the sense that it deals with the notion of being different and with bullying. Those themes sadly are timeless,” says Laurent Bouzereau, author of new book The De Palma Decade: Redefining Cinema with Doubles, Voyeurs, and Psychic Teens.Carrie begins in the same way as the novel. The 16-year-old anti-heroine (Spacek) experiences extreme humiliation in the school showers. She’s pictured in slow motion, looking blissfully happy under the steaming water. Then the trauma begins. She begins to bleed from between her legs, doesn’t understand why, and is overwhelmed by terror. Her religious zealot mother (Piper Laurie) hasn’t taught her anything about her monthly cycles. The other girls mock her, throwing tampons and towels in her direction as she cowers in the corner of the shower cubicle.

“What made him [King] think that a bunch of guys intent (as King puts it) on looking at pictures of cheerleaders who had somehow forgotten to put their underpants on would be riveted by an opening scene featuring gobs of menstrual blood? This is, to put it mildly, not the world’s sexiest topic, and especially not for young men,” Margaret Atwood (author of The Handmaid’s Tale) observed in a recent New York Times article.

Atwood is a huge admirer of the King novel, which she regards as being as much about “all-too-actual poverty and neglect and hunger and abuse” as it is about the “weird stuff” – namely the extrasensory powers that Carrie soon develops.

King was the quintessential blue collar writer. The story of how Carrie first came to be published has long since passed into US literary myth. The down-at-heel author was living in a trailer, working as a teacher in a small town called Hampden and was living in nearby Hermon, a place he later described as the “asshole of the world”. He was trying to write for men’s magazines but not getting very far. He threw an early draft of Carrie into the bin – but the pages were salvaged by his wife Tabby, who was instantly fascinated by her husband’s strange tale about the tormented teenager. “She wanted to know the rest of the story. I told her I didn’t know jackshit about high school girls,” King remembered in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. She told him, “You’ve got something.” The publishers agreed and his career was launched.

De Palma was far too baroque a filmmaker to show much interest in the social realist elements of King’s novel. Instead, he directs in a stylised and extravagant way. The maverick auteur throws in moments of incongruously morbid humour, using split screen to add to the epic quality of the storytelling. He cuts the main set piece – Carrie being drenched in pig’s plasma at the end of the school prom – in exhaustive detail, choreographing it as if it were a complex battle scene.

Carrie is steeped in blood from beginning to end. The director, though, was at pains to explain this was make-believe, made from corn syrup and dye and designed to be “theatrically red”.

As a youngster, the filmmaker had spent a lot of time in hospital, watching his father, an orthopaedic surgeon, at work.

“He [De Palma] worked in the wards from a very young age and saw absolutely horrendous things, which made him somewhat immune to violence and blood,” Bouzereau tells me. “You can’t imagine how much blood is flying around in an operating room,” the director himself recalled in the 2016 documentary De Palma. The implication was clear: if he’d really wanted, he could have made the film far nastier and far darker.

Carrie was as much a distorted fairytale as a conventional horror pic. The tone veers from creepiness to high camp; nearly 50 years on, it continues to wrongfoot and discomfit audiences. Atwood points out that the novel was written when “the second wave women’s movement was at full throttle” but the early scenes of the film showing naked teenage girls cavorting in the changing rooms are uncomfortably voyeuristic.

At times, for instance when Carrie uses her psychic powers to make kitchen knives fly off walls, or when a blood-stained arm suddenly shoots out of a grave, the movie skirts close to the madcap Gothic world of a Tim Burton fantasy. Spacek, though, plays her character with such earnest and emotional rawness that she defies audiences to laugh at her.

The young star had painted sets on De Palma’s earlier 1974 movie, Phantom of The Paradise (she was married to the production designer Jack Fisk, whom she met on her breakthrough film Badlands). When she did her screen test, she was already in her mid-twenties, far too old and also seemingly far too demure for a tortured soul like Carrie. She smeared vaseline in her hair, dirtied herself up and behaved in such a feral manner that De Palma knew instantly he had to cast her, despite the studio’s misgivings.

Spacek explained how she got in character: “I went to that place where all teenagers spend a lot of time, where you’re the victim and everybody hates you and you’re locked in your room, writing poetry and hating your mother.”

It’s so difficult for me; I change it all the time. For classics, it would probably be “Bride of Frankenstein.” I do love that with all my heart. I love “Rosemary’s Baby.” “The Exorcist.” You can watch those again and again and again, and the acting is just so strong. But I love a down-and-dirty 1972 film by a young Brian De Palma called “Sisters.” It has some of the best split-screen in the history of cinema. There’s a performance by Margot Kidder… Conjoined twins freak me out anyway, but there’s an actor. More recently, I love “Longlegs.” I love “Get Out.” I don’t want to live in a world without Jordan Peele movies.

"Of all the movies shot in Dallas," Seitz begins, "Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise is the most singularly odd. Considering the existence of RoboCop, JFK, Logan’s Run, Office Space, and Mars Needs Women, that may seem like a bold statement. But if you’ve seen Phantom—a rock-and-roll black comedy horror riff on The Phantom of the Opera, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and the legend of Faust shot mostly in the 1,704-seat Majestic Theatre—you’ll nod in agreement. (Those who know, know.) Then you’ll keep nodding and nodding until you’re bobbing your head in time to one of the incandescent songs burned into your memory by Paul Williams, Phantom’s songwriter and costar, whose performance as the film’s villain, Swan—a record producer who signed a pact with Satan, steals songs from a brilliant but unknown composer named Winslow (William Finley), and ruins the poor man’s life—represents the only instance in 1970s American cinema in which a 5-foot-2 actor can be said to loom."

It's a great article, and you'll want to read the entire thing, of course - but here is a brief excerpt:

In an act of programming chutzpah worthy of Winslow, Phantom of the Paradise will be screened October 26 at the Majestic Theatre with Paul Williams in attendance. That means viewers will have the unique opportunity to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the film in the presence of the actor who plays the bad guy and watch the hero garrote, bludgeon, crush, stab, and electrocute his enemies on a 30-foot-high screen in the same venue where the movie was shot.Phantom was born in a moment of Winslow-like righteousness. Sometime in 1969, De Palma was riding in an elevator when he heard a bland Muzak arrangement of the Beatles song “A Day in the Life.” “I thought, ‘Boy, they sure managed to take this really original song and turn it into pap!’ ” he says.

The incident sparked his imagination. He had recently been in England shooting footage for a documentary about rock-and-roll artists, including The Who, The Animals, and The Rolling Stones. “We were shooting them in all the original clubs where they’d played,” De Palma says, “and the producer [of the documentary] also knew Bob Dylan, so I’d spent some long evenings up where Dylan was, so I’d gotten to learn a bit about the music industry.”

By that point, De Palma had also spent a few years in the film business, which had its own parasites and predators. “I figured out pretty clearly what I wanted to do,” he says: a rock-and-roll horror film with original songs. Phantom’s antagonists would be the innocent and idealistic composer Winslow, whose Faustian rock-and-roll tragedy becomes a meta-commentary on the movie you’re watching, and Swan, who leeches Winslow’s gifts to ensure the success of the new concert hall he’s opening, then strips the composer of his art, his dignity, his face, his voice, his soul, and even his ability to die. (The contract signed in blood by Winslow specifies that he can’t die until Swan does; you can probably guess what the loophole is.)

The documentary De Palma is talking about was to be titled Mod. Robert Fiore had collaborated with Brian De Palma on several films in the 1960s. Along with Bruce Rubin, Fiore did a little of everything in the De Palma camp. He was the sound recordist on Murder A La Mod (a clip from which ended up playing on a TV in a scene from Blow Out years later). Fiore was the cinematographer on Greetings, and shortly after, co-filmed the split-screen documentary of Richard Schechner's Dionysus In '69 with De Palma and Rubin (the latter recorded the film's sound). Fiore was the cinematographer on To Bridge This Gap, a documentary by Ken Burrows and De Palma, which was edited by Rubin.

There was one other project, a lost documentary from earlier in the 1960s that was to be titled Mod. Fiore, De Palma, Rubin, and William Finley had all shot footage in England. It was Finley's idea, circa 1964, a movie about mods and rockers within a then-burgeoning scene in London. In Justin Humphreys' book, Interviews Too Shocking To Print, Rubin explains that Finley's father had died and left him money, which he was going to use to finance the film. "And I was amazed at the audacity of somebody taking money that they had inherited and immediately spending it on making a movie," Rubin tells Humphreys. "But he was so enthralled by what was going on in London - the whole new music scene and he wanted to document it - to get it on film before it went away because this was the moment of birth for that whole [movement]. I mean, The Beatles were just coming out, and The Stones, and everybody - The Animals, Herman's Hermits, on and on."

After arriving in London ("there was a whole group of us," Rubin says in the book), Finley asked if Rubin would go to France with De Palma to pick up a light Eclaire sound camera, mentioning that he also needed another person to work on the film. Rubin had known Fiore from film school, and De Palma had known Fiore, as well. Fiore happened to be on a Fulbright grant in Paris, "and so he agreed to come back from Paris with us to work on the film," says Rubin, adding that they all had "an incredible two days" in Paris before heading back to London, where they worked on the film for two weeks, "through Christmas and New Year's."

Rubin continues in Humphreys' book:

"Bob Fiore and I went to Birmingham, I think... We drove up there and we went to the Beatles' Cavern (The Cavern Club in Liverpool] and there was a group showing there that night called Herman's Hermits. We got permission - I had a card that said I was from ABC News. I don't know how I got it but people thought that's who I was. They made a lot of things available. We went in and I had enough film to shoot one act of the concert. And it was Herman's Hermits, so I got the camera and Bob Fiore was my sound man at that point. I shot this amazing, exciting number using every element of the zoom lens. It was really very, early '60s exciting experimental cinema. I really shot a great roll of film of Herman's Hermits."And then, right after it was done, and we were out of film, the announcer onstage says, 'And, now, everybody - here's Herman!' I had shot the whole backup group without their leader, so I had wasted every bit of film of some of the most brilliant filmmaking of all-time.

"We were very ragtag as a group and we did what we could do. We did shoot some stuff of a group called The Who in a room in a hotel but nobody had ever heard of them, really, but people were saying, 'This is going to be a big group.' It was a small hotel performing area in a restaurant, like. I did shoot some of their performance."