Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | October 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Before Jake Scully finds his way to Holly Body via Frankie Goes To Hollywood, he distractedly watches a music video on a TV in the house he's taking care of while his new actor friend is in Seattle. The song is "The House Is Burning (But There’s No One Home)" by the band Vivabeat, and the video, directed by Derek Chang, had won an MTV award for Best Video from a New Band. Vivabeat founder Marina Muhlfriedel had met Peter Gabriel in the late 1970's while working as entertainment editor at Teen magazine. Earlier this year, Muhlfriedel wrote an article about Vivabeat for Flood Magazine:

As soon as we wrote our first four songs, we booked time at an 8-track studio off Hollywood Boulevard and cut a new demo. I was ready to reconnect with Peter [Gabriel]. A month later, I went to England, and ringing him from my London hotel, Peter invited me to a party at his home in Bath the following evening. I invited my friend, Rich Barbieri, the keyboard player from the band Japan (now in Porcupine Tree), and he agreed to drive.It was magical—20 or so guests playing croquet by moonlight, surrounded by towering wormwood hedges and sipping peppermint tea. Saying goodbye late in the evening, I didn’t mention to Peter that I left the cassette demo in a fruit bowl on his dining room table.

Nonetheless, a month later, I received a pre-dawn morning call from Peter, introducing me to a jovial Brit named Tony Stratton Smith. Tony owned Charisma Records, the label for which Peter, Genesis, Monty Python, Van der Graaf Generator, among others, recorded. Strat, as he was known, said everyone in his office was whistling “Man From China” and that he had no choice but to take us under the “famous Charisma wing.” We became their first American signing.

This sort of thing did not happen, even in the ’80s. We knew dozens of bands, far more experienced and popular than us. Bands who struggled for years to get a second glance from a label. We played three gigs before suddenly finding ourselves at the Record Plant with Rod Stewart in the next room. We had clothing and equipment allowances. A famous director shot our first video. We signed with the William Morris Agency and were convinced we were on a trajectory to the big time.

Our first album, Party in the War Zone—featuring “Man From China”—came out in 1980. The song became a dance club hit in much of the world, and we got to lip-synch it at all the big gay discos. However, good fortune is often ephemeral. The fact that our first manager’s vanity license plate read “IM SPACED” should have rung a warning bell. It didn’t. Clueless, we forged ahead as he repeatedly dropped the ball. When two band members became heroin addicts and could barely perform, Charisma rejected our demos for a second album and dropped us from the label. And we dropped Connie and Alec from the band.

Soon, our drummer Doug crashed his motorcycle on Fountain Avenue. He was high with no helmet, and Mick found him listed as a John Doe in a coma at Cedars Sinai. He survived, but lost the use of three limbs.

Mick, Terrance, and I pulled together a funkier and more inventive version of Vivabeat with guitarist Rob Dean, who had been in the band Japan, and local session drummer Chris Schendel. We got another manager—and a record deal with Polygram—for a while. But while recording our next album, the manager went AWOL, not returning our calls. Once again, we were in rock ‘n’ roll limbo.

But all was not lost. A couple of dance club promoters released a limited-edition follow-up EP featuring a song called “The House Is Burning (But There’s No One Home).” The song became a European dance club hit and was picked up along with its video (which won an MTV award) to appear in the movie Body Double. Vivabeat was on track to live out a few more fab ’80s cocaine-fueled years, recording some of our strongest work yet. When Rob Dean left Vivabeat for Gary Numan’s band, Jeff Gilbert, a tech-brained San Francisco transplant who later became one of the wizards at Mackie, joined us.

Vivabeat never hit the great big time, but we got a whiff of its heady enchantment, making music we loved, going on the road with bands like Gang of Four, Human League, Depeche Mode, Gary Numan, Thompson Twins, and The B-52’s (R.E.M. opened for us). We also found a dream production partner in Earle Mankey, who got us like no one else.

Discussing the Visco glasses worn by several IMF agents in the opera gala sequence, Dapkunaite tells the podcast hosts, "You know, the glasses, those days, thirty years ago, they were miracle glasses - they literally go dark...and blank."

"Oh, those were a real thing...?" one of the hosts responds.

"Yes, they were the real thing," Dapkunaite confirms.

"Oh, I thought that was just an effect," he says.

"They were the real thing," she assures him. "We carried them as if they were, I don't know, made of diamonds. Which probably, they cost that much. And Tom [Cruise] was very very cool about it. Very proud and all that. So we all played with them."

--------------------------------------------------------------------

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

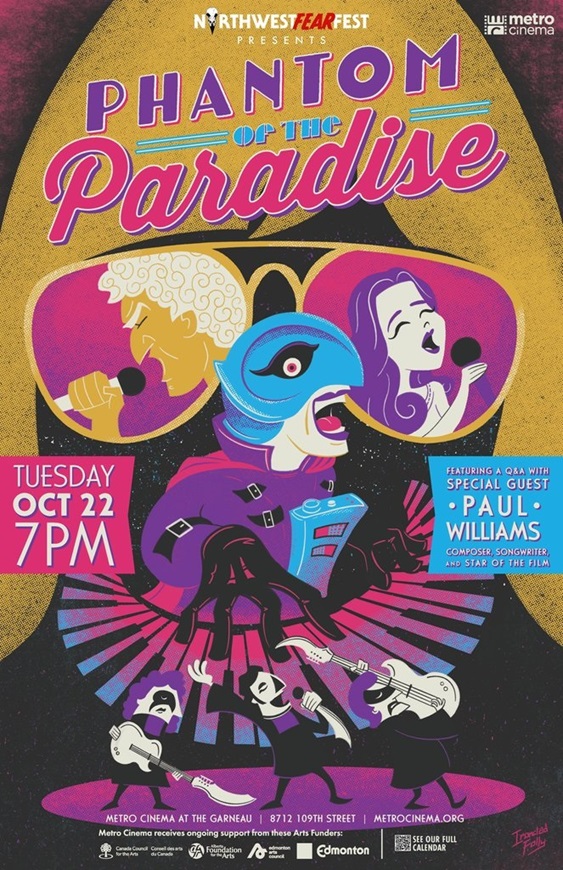

Here's Griwkowsky's intro to the Edmonton Journal article:

Living a life of unparalleled collaboration, Paul Williams is surely the only person on Earth able to claim a direct creative pipeline to David Bowie, Barbra Streisand/Kris Kristofferson and Kermit the Frog, all of whom sang his lyrics to the world — including Hunky Dory’s Fill Your Heart, A Star Is Born’s Grammy-winning Evergreen, and the immortal Muppet Movie opening theme, Rainbow Connection.Remarkably, it’s just the tip of Williams’ creative iceberg.

His staggeringly diverse accolades stretch back to a different Grammy win with Daft Punk in 2014, singing with a lit cigarette in full Battle for the Planet of the Apes makeup on Johnny Carson in ’73, co-writing We’ve Only Just Begun and Rainy Days and Mondays for The Carpenters — never mind penning the words to The Love Boat theme!

Insanely, the list goes on, including voicing the beloved Batman Animated Series’ Penguin amid countless guest spots on everything from Babylon 5 to The Hardy Boys, occupying a Hollywood Square in the midst of it all.

To try and zoom in like that helicopter shot into Kermit’s swamp, the 84-year-old legend is here Tuesday at Metro Cinema for NorthwestFEARFest’s closing–night, 50th-anniversary screening of Brian De Palma’s beautifully weird and musically wondrous cult classic Phantom of the Paradise, scored by and indeed starring Williams.

In a long and magnificent conversation I can just barely sample here, the Oscar/Grammy/Golden Globe-winner talks about it all, laughing as he asks to flip from the phone over to Zoom, “I’m so f—ing old, I listened to everything at 11 for 40 years!”

So much of Carrie now looks, 48 years on, unsubtle to say the least – and yet De Palma is a master of making that lack of subtlety work cinematically. The frankly outrageous soft-porn aesthetic of the initial girls’ locker room scene gives us Spacek almost languorously soaping herself in the shower, in a way that is madly inconsistent with her character. And yet without that absurdly provocative sequence, the “period” moment wouldn’t have been so transgressive, so nasty, so tactless. This is crass, this is the male gaze, sure – and yet it is subverted by its casually explicit violence and vulnerability. It’s impossible to feel anything other than genuine protective concern for a female character who is later to show that she doesn’t need anyone’s protection.And that staggering, drawn-out prom sequence, in which Carrie evolves from ugly duckling to swan to something else entirely – its meaning and atmosphere changes on a subsequent viewing. The first time you watch it, the denouement is a shock, despite the fact that in previous scenes you’ve seen the nasty planning that has gone into it. But the second time, the scene is, end to end, an unbearable ordeal of pure evil: minute after minute goes by while Carrie progressively relaxes and begins to enjoy herself with the wonderful boy who’s taken her on this date. And then, when she unleashes her gonzo uproar of telekinetic rage, De Palma fragments the spectacle with a split-screen: a crazy death metal of carnage.

Carrie is about all the things it didn’t know it was about: internalised misogyny and self-hate, and the theatre of cruelty involved in high school popularity. It isn’t explicitly about school shootings and yet it shows you, like no other film I have ever seen, the horrifying wish-fulfilment ecstasy of such horrific acts. De Palma is the only director who could have done it.

Speaking to Noah Baumbach in the 2015 documentary about his career, De Palma recalls, “I had carte blanche to make this movie, and it was all great until they saw it.” “Body Double” was made in the fallout of financial failures and frustration, cashing in on the recent success of “Scarface” to make an impossible “how did this get made” miracle of a pervert cinema. After years of feeling chewed out by Hollywood, De Palma channeled the anti-establishment anger of his earlier political documentaries into a psychosexual autocritique of himself and his career, as well as a bracing satire of show business and the ghouls inside it. Or, as crime novelist Megan Abbott wrote, “His movies thus become conspicuous, gaudy spectacles of male anxiety and lust, orgies of panicked masculinity in the face of the powerful female.”“Body Double” is the ultimate expression of that theme. Over the last decade, De Palma had a rough run: “Carrie” was a hit, but the Travolta-starring “Blow Out” (a masterwork of paranoia) cost more than “Star Wars” and flopped. He’d just finished a fraught battle with the MPAA over the rating on “Scarface,” and was licking his wounds from a tough divorce with Nancy Allen, his creative muse since “Carrie.”

It was under that industry heat that “Body Double” was born, daring not only to remake one Hitchcock classic but two: a twisted double-bill of “Rear Window” and “Vertigo,” reconceptualized through the pop-kitsch prism of MTV and the lubed backrooms of 1980s hardcore porn. Take the opening scene, with De Palma’s camera panning through an imitation graveyard, tilting into an underground coffin to reveal a bleach-blonde vampire, collared in the couture of S&M. He’s staring at the camera, at us, and we quickly realize something is wrong: a frozen fourth wall break, his fangs and crimson lipstick are unable to move. And then we hear, “Action, Jake. Jake, action…okay cut!” and see a bustling film set.

We were watching Jake Scully (Craig Wasson), a struggling actor. He, like “Scottie” in “Vertigo,” has a crippling psychological flaw. Instead of a dolly-zoomed fear of heights, Jake suffers from debilitating claustrophobia, and he discovers it while shooting the low-rent horror flick “Vampire’s Kiss,” risking ruin to his career. The director tells him to take the rest of the day off, a smiling backstab to fire Jake from the horror picture–the first sign of De Palma’s festering anger towards Hollywood.

This beginning sequence is a fever-dreamed meta-commentary not only on the rest of the movie but the nature of cine-artifice itself. It also recalls the opening of “Blow Out,” another De Palma picture that begins with a film within a film, both movies tricking us into the illusion we’re watching low-grade horror pictures, satirical jabs at the kind of movies De Palma was accused of making. More importantly, they show a sudden branching of one cinematic world penetrating another, an idea reinforced again and again through “Body Double.” This includes even the title card, first revealing a western horizon, only to be then exposed as a matte painting wheeled away into the studio backlot. Should this matte backdrop seem any less “real” because, diegetically, we were shown it was fake when it isn’t any more or less illusory and authentic than when we first saw it? The riddle of suspension of disbelief is a tricky thing, and “Body Double” is a feature-long play on the idea, driving into a climax that turns these tricks into entire setpieces and structural games.