BREAKFAST -

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | October 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

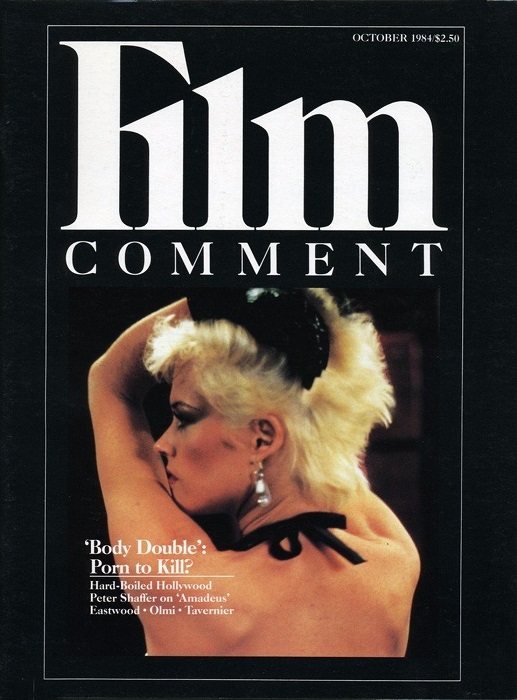

As in Sisters (1972), Obsession (1976), and Dressed to Kill, De Palma draws on Hitchcock’s style and themes in order to create sly pyrotechnics that are entirely his own. If the initial scenes of Jake stalking Gloria nod towards Vertigo (1958), they soon build into an extraordinarily well-choreographed ballet once they reach the Rodeo Collection mall. Largely free of dialogue, and almost entirely carried by movement and Pino Donaggio’s opulent score, it’s a jaw-dropping tour-de-force, playing with geography and perspective. Stephen H. Burum’s stunning camerawork moves up and down and left to right, using every inch of the space while tightly controlling what it wants us to see.Sometimes we know more than the characters (as when we see the ‘Indian’ or the security guard sneak by), and sometimes we’re left as shocked as Jake by a sudden reveal. It’s an astoundingly involving sequence, particularly considering that nothing especially dramatic happens. Admittedly, it draws on Hitchcock’s techniques, but even he was rarely so deliciously audacious in scale, nor so fearless in displaying his own mischievous sleight of hand.

Most controversially, the mall scene and indeed the first half of the film revolve around a man spying on an attractive, troubled woman. Rather than play the scenes subtly, De Palma amps up the slick eroticism to cartoonish levels, as if determined to enrage those who’d considered Dressed To Kill too leering and sexist. Of course, the most implausible and overtly sexualized moments are when Jake watches ‘Gloria’ dance at her window, and these are later revealed not to be her at all. However, it’s left for the viewer to decide whether these deceptive performances by adult actress Holly Body (Melanie Griffith) are a comment on the ludicrousness of straight male fantasies, or whether they’re simply a further example of the unrepentant male gaze in cinema.

Certainly, while she has a broadly similar character arc, Shelton’s Gloria remains passive and underdeveloped compared to Angie Dickinson’s Kate in Dressed to Kill, and the scene in which she kisses Jake despite knowing he’s been following her is ridiculously unlikely (if typically stylish). Likewise, although De Palma has always denied it was intentional, Gloria’s death by drill at the hands of her estranged husband has distinctly phallic overtones, as if designed to enrage feminist critics.

Yet judging these moments in isolation overlooks their context and the deliberate contradictions that run throughout the film. If Gloria’s murder is both horrifying and exploitative (a dichotomy at the heart of all horror cinema), her killer is never portrayed as anything but repugnant. Sam Bouchard (Gregg Henry) exudes arrogance, full of untrustworthy bonhomie and casual misogyny as he ensnares the meek Jake in his schemes. His contempt for others is made chillingly clear by the shot of him standing over Gloria’s body, hands on the drill and foot on her throat, his ‘Indian’ disguise adding blithe racism to his repulsively entitled characteristics.

Further, to suggest that the murder fits with the perceived slasher trope of “punishing” sexually active women is to overlook who replaces the deceased as the new female lead. Like Liz (Nancy Allen) taking Kate’s narrative place in Dressed to Kill, the second half of Body Double belongs to Holly Body—an assertive, strong, and sexually uninhibited woman rather than the traditional virginal ‘good’ girl.

While De Palma plays with puritanical audience expectations, he seems to delight in confounding them. Whether the role of a forthright adult film star is progressive or just more male fantasy is debatable, but it certainly suggests that the director’s world is more complex than the conservative standard attributed to certain slashers. (The fact that he had already spoofed the genre at the start of Blow Out and appears to reference Amy Jones’ 1982 The Slumber Party Massacre with Sam’s choice of murder weapon further implies a playful awareness of the pleasures and limitations of the form.)

Perhaps the most provocative and confrontational aspect of Body Double is the way its games implicate us as viewers. De Palma knows that voyeurism is the essence of cinema, and the more transgressive the sights, the better. Like Jake spying on Gloria/Holly from the dark of his apartment, we know we should look away—but we can’t. It’s no accident that the prominent line of dialogue during the porno movie shoot within the film is “I like to watch”. Nor is it a coincidence that just before showing Jake the telescope that sets the plot in motion, Sam proposes a toast “to Hollywood”.

Indeed, the film’s gleefully tawdry thriller plot is arguably a trojan horse disguising a caustically witty commentary on the dreams and disappointments of Tinsel Town. It emphasizes the tedium and hard work of trying to make it: enduring hostile auditions, attending pretentious acting classes, and surviving the trials and tribulations of cheap B movies like the opening sequence’s Vampire’s Kiss. The film is littered with L.A. landmarks, from the Capitol Records Building and Tail O’ The Pup to the Chemosphere that serves as the location for Jake’s adopted home. By locating its violent climax at the L.A. Aqueduct Cascades, it places the sex, danger, and illusion of the plot on an equal footing with the water supply, as though all these elements are essential to the city.

But the sexual content with which De Palma packed Body Double is potent. He chose Melanie Griffith, then in her mid-twenties, to play porn star Holly Body. He’d met the daughter of Hitchcock star Tippi Hedren while making Scarface; she was the girlfriend of actor Steven Bauer, who plays Tony Montana’s lieutenant Manny in the movie. And Double contains a funny Scarface in-joke. Bauer appears here as one of Holly’s sexual partners in a scene from Holly Does Hollywood, one of Double’s porno-films-within-a-film. He comes into a small room where Holly sits, prepared to do her oral stuff, and is interrupted by a voice on his walkie-talkie saying “Manny, where the hell are you? We need you on set.”Body Double’s plot is a gloss on Hitchcock’s Rear Window, with some morbid femme obsession from Vertigo tempered in. During the height of his career De Palma got a lot of critical smack for his lifts from Hitchcock, but that was unfair. He didn’t take cues from Hitchcock because he was bereft of his own ideas; he did because he knew that the stuff could be constructively and pertinently updated in explicit contemporary terms. In crude terms, it meant he got show things that Hitchcock never could. But it also meant he could make the subtexts in Hitchcock bubble up to a mordant surface.

Heights are the hero’s fear in Vertigo; in Body Double Jake Scully is claustrophobic, which makes his time in a coffin as a glitter-rock vampire (shades of De Palma’s early ‘70s quasi-glam musical Phantom of the Paradise!) in the movie’s opening less than tolerable. He freaks out, gets fired from the schlock movie he’s acting in, and now he’s got an impediment that he has to conquer in his hero’s journey. This journey finds him accepting the generosity of a fellow actor, who sets him up in a crazy ultra-modern UFO-like house in the Hollywood hills; across the way is another house with large horizontal windows and loosely space vertical blinds, and in that house a very scantily clad young woman dances with a remarkable lack of inhibition. Nice for Scully that the joint where he’s housesitting has a top-brand telescope. It’s almost too convenient, right?

And here, for all the rampant sex, corrosive inside-moviemaking humor, and general impertinent attitude, is where we hit the Problematic, in what, it happens, is the movie’s only murder. Given its grisliness, one is all Body Double needs.

You could reasonably make the claim that over the course of the film Paul Williams predicted numerous trends in the music industry. With Somebody Super Like You, he seemed to pre-empt the theatre of bands like Kiss and Goth Rock. Throughout the film, Swan’s group The Juicy Fruits pop up in a variety of guises, performing variations of the Phantom’s work. For this song the group are all dressed as somnambulist Cesare from The Cabinet Of Doctor Caligari, with a stage set that recreates the German expressionist mise en scene. Now called The Undead, this Frankenstein-inspired anthem celebrates an ideal man, assembled from various body parts, creating a campy, terrifying experience. The bone-chilling screams from singer Harold Oblong are incredible, as are his distinctive vocals, full of little tics – “Somebody sssssuper like you!”Incidentally, this was the highest charting song from the soundtrack. It went platinum, but curiously, only in Winnipeg!

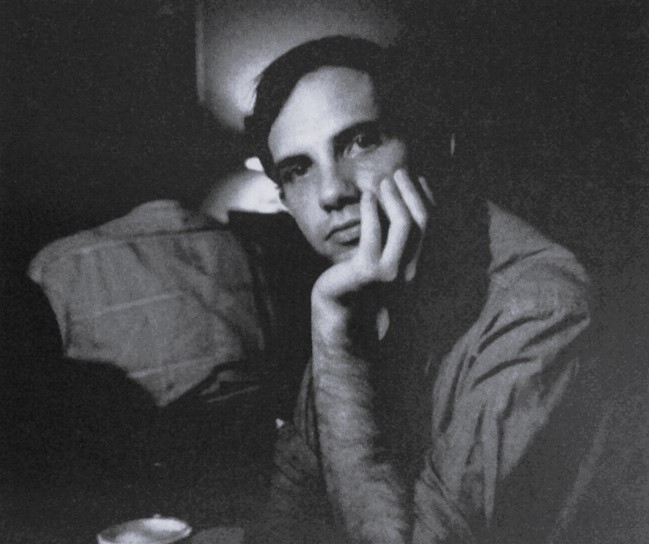

Mr. Morrissey was born on Feb. 23, 1938, in Manhattan to Joseph and Eleanor Morrissey, and grew up in Yonkers, N.Y. He attended Roman Catholic schools and studied English at Fordham University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1955 and began making 16-millimeter silent films. His first effort, a one-reeler, showed a priest saying Mass on a cliff top and then throwing his altar boy over the edge.Despite the subject, Mr. Morrissey was not rebelling against the church. He enjoyed perplexing interviewers by fully endorsing his Jesuit education, heaping scorn on liberals and denouncing sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll even as he presented, without comment, scenes of shocking degradation on film.

“With us, everything is acceptance,” he once said of his collaborations with Warhol. “Nothing is critical. Everything is amoral. People can be whatever they are, and we record it on film.”

After serving in the Army, Mr. Morrissey ran, and lived in, an underground cinema in the East Village, where he showed his own films and those of others, including “Icarus,” an early effort by Brian De Palma. Mr. Morrissey later took pains to explain that he was not part of the experimental-film movement. With his interest in stars and narrative, he was, as he liked to put it, “independent of the independents.”

Mr. Morrissey was introduced to Warhol in 1965 by the poet and filmmaker Gerard Malanga at a film screening, and the Factory phase of Mr. Morrissey’s career began. At the time, Warhol was making experimental films at the commercial loft on East 47th Street known as the Factory. The titles capture their static, impassive aesthetic: “Hair Cut No. 1,” “Shoulder,” “Couch.” The camera stared, unblinking, and whatever happened, happened — or didn’t.

Early in 1958, prior to leaving home in Philadelphia for Columbia University, De Palma had been working to document his father's infidelity by recording his phone calls, following him to work and snapping photos outside his father's office window. According to the book Shock Value by Jason Zinoman, De Palma told one friend that year that the photos were his "first film." In 1970, De Palma mentioned his "background in photography" to Joseph Gelmis (for Gelmis' book The Film Director As Superstar) as he explained how he ended up directing his first short film, Icarus, in 1960:

I started making movies when I was at Columbia University as a sophomore. I was with the Columbia Players, and I had a background in photography. I was obsessed with the idea of directing the Players. But they wouldn't let undergraduates direct them, so I was frustrated. I figured I'd go out and direct movies instead.

Laurent Bouzereau (in The De Palma Cut) states that De Palma "created a film association between Columbia University and Sarah Lawrence College. The famous stage director Wilford Leach, who conducted a theater class at Sarah Lawrence, was immediately impressed by the young man's energy and interest in filmmaking. Leach soon became De Palma's mentor. According to De Palma, Leach was one of the very few people who ever understood him." Bouzereau goes into further detail about the making of Icarus:

In 1960, Brian De Palma made Icarus, which he today considers a pretentious film, though he admits that it encouraged him to learn more. At first, De Palma was only supposed to be the cameraman on Icarus, but the director left the set after many arguments with De Palma, who was already trying to impose his own visual ideas, regardless of his position. Luckily, De Palma was then offered the opportunity to finish the film himself.

WFAA's Paul Wedding has an article about the evening's event:

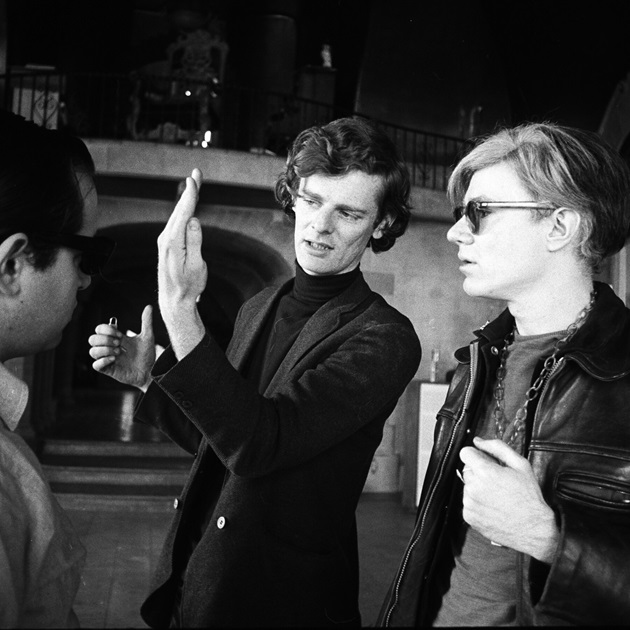

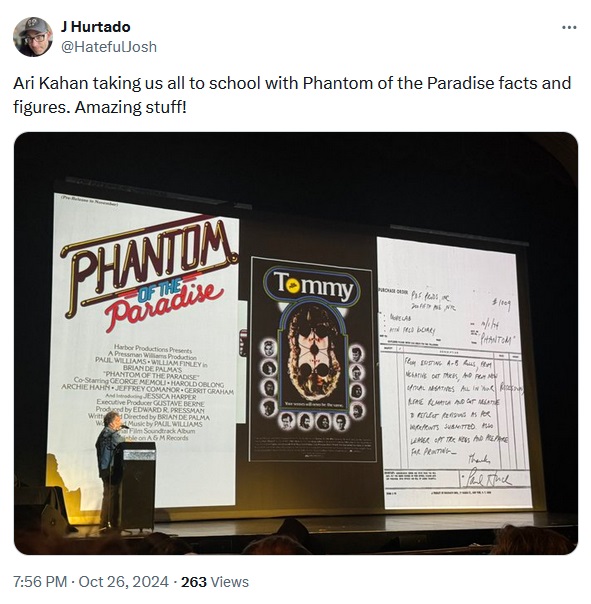

DALLAS — "The Paradise — the ultimate rock palace."That was the Majestic Theatre in Dallas 50 years ago during the filming of the horror musical cult classic, "Phantom of the Paradise." Although considered a box office bomb upon initial release, its influence and fandom have carried on all these decades later.

And on Saturday night, The Majestic got to play the part of the ultimate rock palace once again.

A screening of a restored version of the film was played in the theatre, with a big name in attendance. Paul Williams, a legendary award-winning composer and songwriter, who wrote all of the songs for the film and played the film's antagonist, spoke afterward about the making of the film.

It's not often someone gets to see a movie in the very location it was filmed. So to be able to see a scene in the movie that takes place on a balcony, and then to turn your head and look at that very same balcony — where fans dressed up as the eponymous phantom of the paradise are sitting — is a one-of-a-kind experience.

Shooting the concert scenes of the movie with Dallas residents as extras — some of whom were in attendance for this screening — was not the usual concert. Advertisements in local papers invited extras for a filming of "Phanton (sic) of the Paradise) at 9 a.m. on Thursday. But as Williams tells it, not many people really showed up.

"The fact is that it was cold, and there were not nearly enough people in the audience so there was a lot of moving around," Williams said about the filming of the movie, which took place around Christmas and New Year's.

Before Jake Scully finds his way to Holly Body via Frankie Goes To Hollywood, he distractedly watches a music video on a TV in the house he's taking care of while his new actor friend is in Seattle. The song is "The House Is Burning (But There’s No One Home)" by the band Vivabeat, and the video, directed by Derek Chang, had won an MTV award for Best Video from a New Band. Vivabeat founder Marina Muhlfriedel had met Peter Gabriel in the late 1970's while working as entertainment editor at Teen magazine. Earlier this year, Muhlfriedel wrote an article about Vivabeat for Flood Magazine:

As soon as we wrote our first four songs, we booked time at an 8-track studio off Hollywood Boulevard and cut a new demo. I was ready to reconnect with Peter [Gabriel]. A month later, I went to England, and ringing him from my London hotel, Peter invited me to a party at his home in Bath the following evening. I invited my friend, Rich Barbieri, the keyboard player from the band Japan (now in Porcupine Tree), and he agreed to drive.It was magical—20 or so guests playing croquet by moonlight, surrounded by towering wormwood hedges and sipping peppermint tea. Saying goodbye late in the evening, I didn’t mention to Peter that I left the cassette demo in a fruit bowl on his dining room table.

Nonetheless, a month later, I received a pre-dawn morning call from Peter, introducing me to a jovial Brit named Tony Stratton Smith. Tony owned Charisma Records, the label for which Peter, Genesis, Monty Python, Van der Graaf Generator, among others, recorded. Strat, as he was known, said everyone in his office was whistling “Man From China” and that he had no choice but to take us under the “famous Charisma wing.” We became their first American signing.

This sort of thing did not happen, even in the ’80s. We knew dozens of bands, far more experienced and popular than us. Bands who struggled for years to get a second glance from a label. We played three gigs before suddenly finding ourselves at the Record Plant with Rod Stewart in the next room. We had clothing and equipment allowances. A famous director shot our first video. We signed with the William Morris Agency and were convinced we were on a trajectory to the big time.

Our first album, Party in the War Zone—featuring “Man From China”—came out in 1980. The song became a dance club hit in much of the world, and we got to lip-synch it at all the big gay discos. However, good fortune is often ephemeral. The fact that our first manager’s vanity license plate read “IM SPACED” should have rung a warning bell. It didn’t. Clueless, we forged ahead as he repeatedly dropped the ball. When two band members became heroin addicts and could barely perform, Charisma rejected our demos for a second album and dropped us from the label. And we dropped Connie and Alec from the band.

Soon, our drummer Doug crashed his motorcycle on Fountain Avenue. He was high with no helmet, and Mick found him listed as a John Doe in a coma at Cedars Sinai. He survived, but lost the use of three limbs.

Mick, Terrance, and I pulled together a funkier and more inventive version of Vivabeat with guitarist Rob Dean, who had been in the band Japan, and local session drummer Chris Schendel. We got another manager—and a record deal with Polygram—for a while. But while recording our next album, the manager went AWOL, not returning our calls. Once again, we were in rock ‘n’ roll limbo.

But all was not lost. A couple of dance club promoters released a limited-edition follow-up EP featuring a song called “The House Is Burning (But There’s No One Home).” The song became a European dance club hit and was picked up along with its video (which won an MTV award) to appear in the movie Body Double. Vivabeat was on track to live out a few more fab ’80s cocaine-fueled years, recording some of our strongest work yet. When Rob Dean left Vivabeat for Gary Numan’s band, Jeff Gilbert, a tech-brained San Francisco transplant who later became one of the wizards at Mackie, joined us.

Vivabeat never hit the great big time, but we got a whiff of its heady enchantment, making music we loved, going on the road with bands like Gang of Four, Human League, Depeche Mode, Gary Numan, Thompson Twins, and The B-52’s (R.E.M. opened for us). We also found a dream production partner in Earle Mankey, who got us like no one else.

Discussing the Visco glasses worn by several IMF agents in the opera gala sequence, Dapkunaite tells the podcast hosts, "You know, the glasses, those days, thirty years ago, they were miracle glasses - they literally go dark...and blank."

"Oh, those were a real thing...?" one of the hosts responds.

"Yes, they were the real thing," Dapkunaite confirms.

"Oh, I thought that was just an effect," he says.

"They were the real thing," she assures him. "We carried them as if they were, I don't know, made of diamonds. Which probably, they cost that much. And Tom [Cruise] was very very cool about it. Very proud and all that. So we all played with them."

--------------------------------------------------------------------

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Newer | Latest | Older