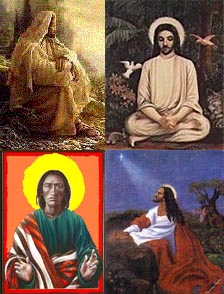

Views on the Nature of Jesus:

Trinatarinism

Taken from Wikapedia

Trinity is the doctrine that God is one being who exists, simultaneously and eternally, as a mutual indwelling of three persons (not to be confused by "person"): the Father, the Son (incarnate as Jesus of Nazareth), and the Holy Spirit. Since the 4th century, in both Eastern and Western Christianity, this doctrine has been stated as "three persons in one God," all three of whom, as distinct and co-eternal persons, are of one indivisible Divine essence, a simple being. The doctrine also teaches that the Son Himself has two distinct natures, one fully divine and the other fully human. Supporting the doctrine of the Trinity is known as Trinitarianism. Most divisions of Christianity are Trinitarian, and regard belief in the Trinity as a test of Christian orthodoxy.

Opposing nontrinitarian positions held by some groups include Binitarianism (two deities/persons/aspects),Biblical Uniatarians, Unitarianism (one deity/person/aspect), the Godhead (Latter Day Saints) (three separate beings, one in purpose) and Modalism (Oneness).

(See below) Historically, the doctrine of Trinitarianism is of particular importance. The conflict with Arianism, as well as other competing theological concepts during the fourth century, became the first major doctrinal confrontation in Church history. It had a particularly lasting effect within the Western Roman Empire where the Germanic Arians and Nicene Christians formed a segregated social order.

Etymology

The concept came to be called the "Trinity" in later years. The word comes from "Trinitas," a Latin abstract noun that means "three-ness," "the property of occurring three at once" or "three are one." The Greek term used for the Christian Trinity, "ÔñéÜò" ("Trias," gen. "Triados") means "a set of three" or "the number three,"[1] and has given the English word triad.

The first recorded use of the word "Trinity" in Christian theology was in about AD 180 by Theophilus of Antioch who used it, however, to refer to a "triad" of three days: the first three days of Creation, which he then compared to "God, his Word, and his Wisdom."[3][4] He compared the fourth day to humanity, as a needy recipient of the first three, forming a tetrad. The creations in the fourth, fifth, and sixth days are said to intimate both righteous and unrighteous members of humanity. God rested in the seventh day, the Sabbath.

Tertullian, a Latin theologian who wrote in the early third century, is credited with using the words "Trinity" and "person" to explain that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit were "one in essence— not one in Person."[5]

About a century later, in AD 325, the Council of Nicea established the doctrine of the Trinity as orthodoxy and adopted the Nicene Creed that described Christ as "God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made,being of one substance (homoousios) with the Father."

Trinity in Scripture

Sculptural group from the Holy Trinity Column in Olomouc, Czech Republic, 18th centuryNeither of the words "Trinity" nor "Triunity" appear in the Old Testament or New Testament. Various passages from both have been cited as supporting this doctrine, while other passages are cited as opposing it.

Summarizing the role of Scripture

The Apostle John is identified as the "one whom Jesus loved" thus perhaps being the closest Apostle to Jesus. In John 19:26, Jesus also instructed John to adopt Jesus' mother Mary as John's own in Mary's old age, [4] such that John would have had the entire knowledge of Jesus' family when writing his Gospel. John opens the Gospel of John by declaring "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was * God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made." The rest of John Chapter 1 makes it clear that "the Word" refers to Jesus the Christ.

Thus John introduces a seemingly impossible contradiction, that Jesus both "was with God" and "was God" at the same time, and that from the beginning of creation. John also portrays Jesus Christ as the Creator of the Universe, such that "without him nothing was made that has been made." [5] Such a paradox is fundamentally impossible, and it is thus believed that it could only be fulfilled by a divine being to be both with God and to be God at the same time. John also argues for the divine nature of Jesus.

Jesus frequently referred to the "Father" as God as distinct from Himself, but also discussed "The Holy Spirit" as a being distinct from either God the Father or Jesus Himself. ' "These things I have spoken to you while abiding with you. But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in My name, He will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I said to you." John 14:25-26 [6] In this passage, Jesus portrays the Father sending the Holy Spirit -- that is the Father and the Holy Spirit are two distinctly different persons, and portrays both the Father and the Holy Spirit as distinct from Jesus Himself. Thus even apart from whether Jesus was God, Jesus tells us that the Father and the Holy Spirit are two different persons, both of them Divine.

The Old Testament depicts God as the father of Israel and refers to (possibly metaphorical) divine figures such as Word, Spirit, and Wisdom. Some biblical scholars have said that "it would go beyond the intention and spirit of the Old Testament to correlate these notions with later Trinitarian doctrine."[6] According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, a few of the Fathers "found what would seem to be the sounder view" that "no distinct intimation of the doctrine was given under the Old Covenant." [7][8)

The New Testament also does not use the word (Trinity), nor explicitly teach it.[11] The Trinity article in Encyclopedia Britannica states: "Neither the word Trinity nor the explicit doctrine appears in the New Testament, nor did Jesus and his followers intend to contradict the Shema in the Old Testament: "Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord" (Deuteronomy 6:4)."[12 ]Encyclopedia of Religion, for example, argues that "God the Father is source of all that is (Pantokrator) and also the father of Jesus Christ. Early liturgical and creedal formulas speak of God as "Father of our Lord Jesus Christ"; praise is to be rendered to God through Christ (see opening greeting in Paul and deutero-Paul). There are other binitarian texts (e.g., Romans 4:24; Romans 8:11; 2 Corinthians 4:14; Colossians 2:12; 1 Timothy 2:5–6; 1 Timothy 6:13; 2 Timothy 4:1), and a few triadic texts (the strongest are 2 Corinthians 13:14 and Matthew 28:19)."[6]

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, while Trinity does not explicitly appear in the New Testament, its basis is established by the New Testament: The coming of Jesus Christ and the presumed presence and power of God among them had implications for the early Christians. "The Holy Spirit, whose coming was connected with the celebration of the Pentecost. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit were associated in such New Testament passages as the Great Commission: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (Matthew 28:19); and in the apostolic benediction: "The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all" (2 Corinthians 13:14)."[12] The Great Commission reflects the baptismal practice at Matthew's time (or later if this line is interpolated, according to The Oxford Companion of the Bible). Aside from this verse, although "Matthew records a special connection between God the Father and Jesus the Son (e.g., Matthew 11:27), but he falls short of claiming that Jesus is equal with God (cf. 24:36)."[13]

According to The Oxford Companion of the Bible, 2 Corinthians 13:14 is the earliest evidence for a tripartite formula. The Oxford Companion of the Bible states that it is possible that this three-part formula was later added to the text as it was copied. However, there is support for the authenticity of the passage since its phrasing "is much closer to Paul's understandings of God, Jesus and the Holy Spirit than to a more fully developed concept of the Trinity. Jesus, referred to not as Son but as Lord and Christ, is mentioned first and is connected with the central Pauline theme of grace. God is referred to as a source of love, not as father, and the Spirit promotes sharing within community."[13]

The Gospel of John does suggest the equality and unity of Father and Son. ("I and the Father are one" John 10:30). This Gospel starts with "the affirmation that in the beginning Jesus as Word "was with God and ...was * God" (John 1:1) and ends with Thomas's confession of faith to Jesus, "My Lord and my God!" (John 20:28)."[13]14]

Monophysitism Trinatarinism

This is the view held by the Eastern Orthodox churches, that Jesus was only one person with one nature, a blend of humanity and deity. Hanson suggests that the Jesus portrayed in the Gospel of John “is moving towards Monophysitism. His Jesus is a monophysite figure in the sense that he seems to be a blend of divine and human…where the Transfiguration is taken as an index of Jesus’ real person while on earth.” [5] Cullman sees this same thinking in the average Roman Catholic, even though the Church has condemned it as heresy.

Despite its official condemnation, Monophysitism still dominates the religious thinking of the average [Roman] Catholic. Jesus and God are often no longer distinguished even by terminology. The question has rightly been raised whether the need for veneration of Mary has not perhaps developed so strongly among the Catholic people just because this confusion has made Jesus himself remote from the believer. [6]

Cullman’s observation that Jesus and God are not distinguished even in terminology seems to be an accusation that would apply to Trinitarianism in general. The customary distinction is between the “Father” and the “Son,” not between “God” and “Jesus.” The position of the orthodox Church is that Christ has two different natures, with two wills, one human and one “God,” that coexist in him. We believe that Scripture testifies to Christ as the Last Adam, a man like us, having one nature and therefore one will.

Monotheism (Serial)

In American Church history, the Protestant majority has remained Trinitarian chiefly by practicing serial monotheism—focusing now on one, now on another member of the Holy Trinity. Apparently this is a practical accommodation to confusing Trinitarian terminology that can be avoided if one does not try to talk about all three persons in one breath.

Sabellianism or Modalism

So called because God is thought to have three modes of being rather than existing simultaneously and eternally as three distinct persons. Sabellius taught that the Godhead was a monad, expressing itself in three operations: as Father, in creation; as Son in redemption; as Holy Spirit, in sanctification. The Oneness Pentecostals are criticized for taking this position, because for them Jesus is the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Michael Servetus, in his critique of the Trinity, proposed a semi-Sabellian idea that Christ and the Holy Spirit are merely representative forms of the one Godhead, the Father. Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg also taught a form of this doctrine and would later influence the creation of Metaphysical/Christian beliefs systems of The Unity Church, as well as Religious Science.

______________________________________________________

Biblical Unitarianism

From Wikepedia

Nontrinitarianism

Some Christian traditions either reject the doctrine of the Trinity, or consider it unimportant. Persons and groups espousing this position generally do not refer to themselves as "Nontrinitarians." They can vary in both their reasons for rejecting traditional teaching on the Trinity, and in the way they describe God. Following is an outline of basic objections raised by critics of the Trinity and a theologian's defense of each:[53] The word Trinity is not found in the Bible. Response: This has no bearing on whether or not the Bible teaches the doctrine. The word "monotheism" is also not in the Bible and yet the concept is clearly taught in scripture. There is no verse in the Bible that teaches the Trinity. Response: Various verses teach that the Father is called God Phil. 1:2, the Son is called God (John 1:1,14, and the Holy Spirit is called God (Acts 5:3-4). There are verses that suggest the Trinity since they mention all three together: Matt. 3:16-17. Matt. 28:19, 2 Cor.13:14 The Trinity is three separate Gods. Response: The Trinity doctrine, by definition, is monotheistic. The Shema of the Old Testament (Deut. 6:4) is seen in the New Testament ("The Lord our God is one." Mark 12:29). The New Testament knows God as Father, as Son, and as Holy Spirit. Three gods cannot be one God. Response: The Trinity is not three gods. The Trinity is one God in three persons, or three aspects or faces of a single God. Three persons cannot be one person. Response: The Doctrine of the Trinity does not state that God is one person. The Trinity is one God in three persons. Moreover, the understanding of mortal humans in our limitations in the world cannot be applied to an infinite, supernatural God. Anything can be true of God, for "with God all things are possible." That is, doubters of the doctrine limit God to Man's nature and do not account for God's infinite capabilities and infinite complexity. The Trinity is illogical. Response: There is no logical reason why the Trinity cannot be a possibility. A physical analogy to the spiritual concept would be a sphere: 100% is wide, 100% tall, 100% deep; they are not parts, but individual dimensions of a single essense. Width is not depth, depth is not height, and height is not width, and yet the single sphere is all three. Similarly, the objection views an infinite God from the narrow perspective of Man. If a man were to put his hand into an aquarium in one place, the fish would perceive him in the shape of a hand. If he then put his face in another part of the aquarium, the fish would perceive a face, and not understand that both the hand and the face are the same person. The created universe is so limited and small compared to an infinite God, that the manner in which God appears to us, intruding into the created universe in different places, may severely strain our capacity to understand the nature of God. Critics of the Trinity overlook the Christian belief that God did not "find" the universe, but created it, even creating the very concepts of time, space, dimension, and the laws of physics. Thus, our framework for thinking about God is severely limited within our narrow experience.

The Trinity is a pagan idea. Response: Other religions have included triads (three separate gods) in their theology. The Trinity is one God. There are many verses in the OT that contain plural references to the one God: 1) 1:1-26; NIV Job 33:4; 2) Gen. 17:1; Gen. 18:1; {{Bibleref2|Ex. 6:2-3; 24:9-11; 33:20; {{Bibleref2|Num. 12:6-8; {{Bibleref2|Psalm 104:30; 3) Gen. 19:24 with {{Bibleref2|Amos|4:10-11; {{Bibleref2|Is.48:16} Furthermore, mere similarity in appearance between two beliefs does not dictate that one belief came from the other. Mere coincidence of ideas across religion does not tell us whether those ideas are true as taught by the Bible. It is likely that Biblically-accurate ideas have been transmitted around the world and copied from the Bible. Jesus cannot be God because He did not know all things, slept, grew in wisdom, said the Father is greater than I, etc. Response: We can not make assumptions about the structure within the Trinity of God. For example, my hand obeys my head. And yet both my head and my hand are part of the same person. The fact that my head and feet obey my mind does not make them any less "me." This objection fails to take into consideration the Hypostatic Union which states that Jesus had two natures: divine and human. As a man, Jesus cooperated with the limitations of His humanity. Jesus would sleep, grow in wisdom, and say the Father was greater than He. These do not negate that Jesus was divine since they reference His humanity and not His divinity. That part of God who was (is) Jesus came to Earth in part to demonstrate and model the obedience that each of us should exhibit towards God, and was thus in a sense playing a role. Jesus cannot be God because this would mean that God died and God can't die. Response: Initially, it is said that God cannot die, although in fact God can do whatever God wishes to do. God cannot die -- against his will. But it is projecting Man's nature onto God to say that God cannot do whatever God purposes to do. Furthermore, strictly speaking, the spirit of Man continues after death as well. The physical body of a man may die, yet his spirit continues and goes either to heaven or to hell. So if a human body named Jesus in which God dwelled died, obviously the Spirit of God did not die any more than the spirit of you or I at the time of our death. Jesus' sacrifice was divine, as well as human, in nature. Jesus died. But, we know that God cannot die. So, if the divine nature did not die, how can it be said that Jesus' sacrifice was divine in nature? The answer is that the attributes of divinity, as well as humanity, were ascribed to the person Jesus. Therefore, since the person of Jesus died, His death was of infinite value because the properties of divinity were ascribed to the person in His death. This is called the Communicatio Idiomatum.

Nontrinitarian groups

Since Trinitarianism is central to so much of church doctrine, nontrinitarians have mostly been groups that existed before the Nicene Creed was codified in 325 or are groups that developed after the Reformation, when many church doctrines came into question[54]

In the early centuries of Christian history adoptionists, Arians, Ebionites, Gnostics, Marcionites, and others held nontrinitarian beliefs. The Nicene Creed raised the issue of the relationship between Jesus' divine and human natures. Monophysitism ("one nature") and monothelitism ("one will") were heretical attempts to explain this relationship. During more than a thousand years of Trinitarian orthodoxy, formal nontrinitarianism, i.e., a doctrine held by a church, group, or movement, was rare, but it did appear. For example, among the Cathars of the 13th century. The Protestant Reformation of the 1500s also brought tradition into question. At first, nontrinitarians were executed (such as Servetus), or forced to keep their beliefs secret (such as Isaac Newton). The eventual establishment of religious freedom, however, allowed nontrinitarians to more easily preach their beliefs, and the 19th century saw the establishment of several nontrinitarian groups in North America and elsewhere. These include Christadelphians, Jehovah's Witnesses, The Abraham Faith Church of God (Open Bible Church) The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Unitarians. Twentieth-century nontrinitarian movements include Iglesia ni Cristo and the Unification Church. Nontrinitarian groups differ from one another in their views of Jesus Christ, depicting him variously as a divine being second only to God the Father (e.g., Jehovah's Witnesses), Yahweh of the Old Testament in human form, God (but not eternally God), Son of God but inferior to the Father (versus co-equal), prophet, or simply a holy man.

Of notable exception are Oneness Pentecostals, who affirm that God came to Earth as man (i.e., manifested Himself) in the man Jesus Christ. Oneness Pentecostals fully affirm, like Trinitarians, that Jesus Christ is fully God and fully man. One can understand Oneness Pentecostals by replacing the Trinitarian term 'person' with the term 'mode' or 'manifestation' when discussing the Christian Godhead. Many Oneness Pentecostals can recite the first Nicene Creed, as it rejects Arianism, yet preserves the oneness of God and divinity of Jesus Christ.

______________________________________________________

Infomation based on and taken from

BiblicalUnitarians.org

Separationism

The view that a spirit being called “Christ” came into the man Jesus at his baptism, and left him again before his crucifixion. Thus, “Jesus” and “Christ” were separate individuals.

Subordinationism

This is the view that Jesus is subordinate to God and therefore not eternally co-equal. Eastern Orthodox Churches teach that Christ has a subordinate rank to the Father while still maintaining his deity. More extreme forms forbid “prayer” to Jesus Christ as inappropriate and even devilish.

Divinatarianism (homoousios arianism)

In the views of Christianities, there is widley popular trinitarianism in which Jesus is viewed as God. Then there is what has come to be termed as Bibical Unitarianism in which Jesus is viewed a not God but the highest reflection rather than incarnation of God who become Savior when he rose from the grave and sat at the right hand of God. Bibical unitarianism is vastly different from simply unitarianism, in which most UU Christians embrace the idea that Jesus is not Savior nor God's Son but simply a positive spiritual teacher. But there is yet another view of Christ. I call it divinatarianism, in which like with bibical unitarianism, Jesus is viewed as the highest refelction of God rather than incarnation. Jesus Christ is viewed as savior, but believes that Christ had a pre-life in heaven before being born on earth in human form. They believe Christ was the first being that God created directly, and that through Jesus, God created all other things, and as such Jesus is divine in nature because of this. The belief that Jesus was the first of all created beings, pre-existent but eternally subordinate to God, being of different substance from the Father (heterousios). Jehovah’s Witnesses, The Laymen's Home Missionary Movement, Epiphany Bible Students.

Adoptionism

Christ was a fully flesh-and-blood human being, not pre-existent or, for most adoptionists, born of a virgin. They teach that Christ was not born the Son of God, but was adopted as such at some point later in his life (his baptism, his resurrection, etc.) Christadelphians, Abraham Faith Church of God (Open Bible Church).

BIBLIOGRAPHY Dowley, T. The History of Christianity rev. ed. Oxford: Lion Publishing, 1990.

Frend, W.H.C. The Early Church. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985.

Gonzalez, J.L. A History of Christian Thought, vol. 1, 3rd printing. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1970.

Hughes, P. A History of the Church, vol. 1. London: Sheed and Ward, 1979.

Jackson, F.J.F. The History of the Christian Church to A.D. 461. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1965.

Jedin, H. History of the Church, vol. 2. London: Burns & Oates, 1980.

Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Creeds, third ed. London: Longman Group Ltd., 1972.

Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Doctrines, fifth ed. London: A&C Black, 1989.

Newman, J.H. The Arians of the Fourth Century. London: Longmans Green and Co., 1909.

Williams, R. Arius Heresy and Tradition. London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1987.

Biblical Unitarians Articles:

http://www.biblicalunitarian.com/modules.php?name=Top

Back To Articles

Back to Main Page