(c) Copyright 2002 - 2019

Kenneth R. Conklin, Ph.D.

All rights reserved

Hawaiian sovereignty activists like to say that "Hawaiian language was made illegal." They like to say that "Here in our own homeland we were forbidden from speaking Hawaiian, and our grandmothers have told us how they were punished for speaking it."

The activists like to say Hawaiian language was illegal because it magnifies their claim to victimhood status. It's one more way those haole oppressors turned the natives of this land into a poor, downtrodden people who have the worst statistics for education, health, incarceration drug abuse, etc. "Those haoles stole our land, and our nation, and even made our language illegal right here in our own homeland. So of course we're angry, we feel deep pain, and we're entitled to huge reparations for the damage done to us."

The editor of this website, Ken Conklin, has personally heard and seen such claims frequently asserted on TV, in Hawaiian history and language classes, and in published newspaper articles, since first coming to live permanently in Hawai'i in 1992. Some Maui high school students started publishing letters to editor trumpeting this claim in December 2003; at which point Ken Conklin decided to begin accumulating these statements for posterity. See:

https://www.angelfire.com/hi2/hawaiiansovereignty/hawlangpublvictclaims.html

But of course, today we know that there were Hawaiian language newspapers publishing continuously, right up through about 1948 when they finally died out. Hawaiian language was spoken in the Hawai'i Territorial Legislature in the early 1900s. And yes, if granny spoke Hawaiian in school as a little girl she might have been punished by the teacher, just as the little Japanese girl was punished for speaking Japanese. But even at home, granny as a little girl might have been punished by her own parents for speaking Hawaiian in the home, because the parents recognized that the path to social and economic success would be through English. The parents would speak to each other in Hawaiian, but would speak only English with their children. The parents did that not because the language was illegal, but rather because they wanted what was best for their beloved children.

In recent years we have learned that Hawaiian language was not banned in the society and culture of Hawai'i, and remained in everyday use in newspapers etc. But the remnant of the "illegal language" claim is that Hawaiian language was banned in the schools. That is also absolutely false. Hawaiian language was not singled out -- the law applied to all Asian, European, and other non-English languages as well. Courses where Hawaiian language (or any other language) was the subject matter were specifically allowed by the carefully written law. The law applied only to require the use of English to teach non-language courses, such as math, science, history, etc. The law did not prohibit private schools for after-school instruction in language and culture. The law only said that such "immersion" schools could not be the main school attended by a child that the government would recognize as meeting the compulsory school attendance law.

Perpetuating this myth, that Hawaiian language was banned in society, or in school, serves the agenda of the sovereignty activists to portray ethnic Hawaiians as victims and to stir up resentment and anger. Thus the need for this webpage.

This webpage consists of three parts: (1) A personal note by Ken Conklin, describing my 10-year odyssey toward learning the carefully-hidden truth about "suppression of Hawaiian language"; (2) What the law actually said, and why Hawaiian language nearly died out; (3) English has become the dominant language throughout the world in international venues, and there are some multi-ethnic nations today where government imposes a "major" foreign language on all citizens by consent of all ethnicities to facilitate communication.

It turns out that laws favoring English were probably targeted primarily to assimilate the American-born children (U.S. citizens) of Japanese plantation workers, whose parents clung tenaciously to Japanese language and culture, rather than to assimilate ethnic Hawaiians. The laws favoring English had virtually no effect on native Hawaiians because they had already moved overwhelmingly into using English as their primary language; whereas the laws had a great effect on tens of thousands of ethnic Japanese families. There were important legal battles regarding the impact on Japanese, but no legal battles over Hawaiian language.

==================

(1) A personal note by Ken Conklin, describing my 10-year odyssey toward learning the carefully-hidden truth about "suppression of Hawaiian language"

When I moved to Hawai'i to live here permanently in summer 1992, I immediately signed up to take courses in Hawaiian language, history, and culture beginning in September. I was repeatedly told by the instructors and by my fellow (ethnic Hawaiian) students that Hawaiian language had been illegal right up until only a few years previously. They said that after the overthrow of the monarchy in 1893, the Provisional Government and its successor the Republic of Hawai'i had passed a law making Hawaiian language illegal. The purpose of the law was allegedly to oppress kanaka maoli; to strip them of their language and culture in order to force them to assimilate to American culture. This suppression of the language and culture was accompanied by the theft of Hawaiian land accomplished by the illegal Republic of Hawai'i ceding the government and crown lands of the Kingdom to the U.S. as part of the illegal annexation of 1898. My instructors and fellow students told me they had heard their grandmothers telling stories of being punished for speaking Hawaiian.

But as I learned more, I began to question what I was being told. For example, I was also told that the Constitution of the State of Hawai'i (resulting from a Constitutional Convention in 1978) declared that Hawaiian and English are the two official languages of the State of Hawai'i. So, how could Hawaiian language have been illegal after it was made an official language in 1978? And why were all the street names Hawaiian? And how did the songs and hulas and genealogies get passed down through the latest several generations if the language was truly illegal? (the silly answer given by the activists: "It was done in secret"!) I asked for the names of even a few people who had been arrested for speaking Hawaiian, but none were forthcoming. I asked for a citation of the laws in the Hawai'i statutes that made the language illegal, and nobody could provide them. I was already pressing the limits of cordiality by asking such "niele" (overly inquisitive) questions, and to press harder would have been considered "maha'oi" (rudely impertinent, or perhaps "politically incorrect").

Summer 1998 was a commemoration of the 100th anniversary of annexation. Hawaiian sovereignty propagandists had "rediscovered" a long-forgotten petition against a treaty of annexation. The petition had been created and delivered to the U.S. Senate in 1897 and had been safeguarded in the National Archives all along -- and it was written in Hawaiian language! So, clearly the language was not illegal in 1897. The sovereignty activists also mentioned some anti-annexation articles that had been published in Hawaiian-language newspapers! Clearly the language was not illegal. Later I learned that Hawaiian-language newspapers had been published continuously right up to about 1950 when they finally died out for lack of readership.

Finally, six years after I started asking questions, a Hawaiian sovereignty activist who had some respect for the facts told me that the Hawaiian language had never been completely illegal; but that a law had been passed in 1896 (Republic of Hawai'i) making the language illegal in schools. My informant told me the language was made illegal in all the schools, both public and private, and that indeed children were punished for speaking Hawaiian in school. I was told that the purpose of this law was to "haolefy" the children and colonize their minds; i.e., to diminish the influence of Hawaiian culture and language in the formation of the children's minds and to force the children to assimilate to American culture and English language (turn ethnic Hawaiian children into coconuts -- brown on the outside but white on the inside). The purpose was to oppress kanaka maoli and destroy their culture.

As the evils of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement became more clear to me and I began making public statements in opposition to that agenda, I continued asking questions about this law from 1896 that made the Hawaiian language illegal in all the schools. Finally, in summer 2002 I discovered the truth, explained in part (2) below.

Twisting history is an activity where Hawaiian sovereignty activists have great expertise. Many of them simply don't know the truth. Some know only certain portions of the truth which were told to them in distorted ways. A few actually know enough of the truth to realize that what the activists are saying is nonsense, yet they knowingly continue to commit historical fraud. One such fraud is the claim that Hawaiian language was completely illegal, or that at least it was illegal in the schools. It is very easy for someone to say "They stole our nation. They stole our land. They made our language illegal in order to oppress us and force us to assimilate." It is then easy for dozens more people to shout such nonsense. The nonsense takes only ten seconds to say. It takes a long time to do the research, and a long time to explain the truth. Citizens of Hawai'i and of the U.S. must no longer allow the sovereignty activists to commit historical fraud. That's why this website is called "Hawaiian sovereignty: thinking carefully about it." That's one reason why this page on the "illegal" Hawaiian language is so important -- it probes deeply into one particular falsehood and serves as an example of how such falsehoods are perpetuated in service to the Hawaiian victimhood grievance industry.

=================

(2) What the law actually said, and why Hawaiian language nearly died out.

Most nations or their political subdivisions (like the states of the United States) have laws protecting children from physical and economic abuse. Part of that protection is a compulsory attendance law, requiring children to attend school until they reach an age where they may freely decide whether to remain in school or leave. One purpose of a compulsory attendance law is to ensure that children will get an education enabling them to become productive members of society capable of earning a living in an occupation of their own choice. Part of that purpose is to protect children by ensuring that parents or other adults cannot force children to abandon their schooling at an early age in order to work to support their parents or to provide cheap labor for some farmer, fisherman, or factory.

The Hawaiian kingdom had a compulsory school attendance law, which was continued (with modifications) under the Provisional Government, Republic, Territory, and State of Hawai'i. Any compulsory school attendance law must include a definition of what constitutes a "school." To make sure parents or factories cannot get around the law by establishing sham "schools," the government defines the minimum requirements that must be met before a "school" is certified as meeting the requirements of the compulsory attendance law. Such minimum requirements for facilities, curriculum, and performance review apply to all schools, both government and private. Thus, a government has an agency responsible for certifying schools that meet the requirements. Government certification of schools for purposes of the compulsory attendance law does not prohibit other schools or academies. For example, churches can operate "Sunday schools" for religious instruction, or ethnic groups can set up after-school or weekend academies to perpetuate a culture and language.

Following the revolution of 1893, the Republic of Hawai'i passed a law in 1896 specifying that English must be the language of instruction in any school receiving certification as meeting the compulsory attendance law. Here is the exact wording of that law:

1896 Laws of the Republic of Hawaii, Act 57, sec. 30: "The English Language shall be the medium and basis of instruction in all public and private schools, provided that where it is desired that another language shall be taught in addition to the English language, such instruction may be authorized by the Department, either by its rules, the curriculum of the school, or by direct order in any particular instance. Any schools that shall not conform to the provisions of this section shall not be recognized by the Department." [signed] June 8 A.D., 1896 Sanford B. Dole, President of the Republic of Hawaii.

The law clearly concerns only schools, not society at large. It does not single out Hawaiian language at all -- it applies equally to all languages other than English, including Japanese, Mandarin, Cantonese, Portuguese, etc. (the majority of the children at that time were children of Japanese and Chinese plantation workers, and there were also numerous immigramts from Portugal working on the plantations, mostly as lunas [overseers of small work gangs]). The law does not prohibit establishing private after-school or weekend academies where the medium of instruction could be Hawaiian (or any other language) -- it merely states that such schools will not be recognized by the government as satisfying the requirement that all children must attend school. The law clearly states that Hawaiian (or any other language) may be taught in a language course.

Some ethnic groups, most notably first-generation immigrant Japanese plantation workers, did indeed have private schools for "after school" or weekend instruction in their language and culture (see astonishing information about just how prevalent this was, near the end of this webpage). Many, perhaps most Hawaiian parents went so far as to demand that their children speak only English at home as well as at school. There was simply no desire among Hawaiian parents to set up special academies to perpetuate Hawaiian language. Ethnic Hawaiian plantation workers were legally free to do what the Japanese actually did. The Hawaiians were also being paid at a higher wage rate than the Japanese, who were at the bottom of the scale (until Filipinos started coming to Hawai'i and occupied the bottom). The Japanese felt it was important to invest their time and money to perpetuate their culture and language; while the Hawaiians, to the contrary, felt it was important to demand that their children speak English and assimilate to Euro-American cultural values.

Japanese plantation workers were on three-year contracts and most intended to return to Japan; therefore, they strongly wanted their children to grow up speaking and feeling Japanese. Plantation workers were unskilled laborers and therefore low-paid by the standards of the U.S. or Hawai'i. Yet from 1885 to 1894 they sent back to their families in Japan about $2.5 Million. That was an enormous sum: for example, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Estate including about 400,000 acres of land was valued at only about $300,000 during the probate of her will circa 1886; and the value of all 1.8 million acres of ceded lands in 1898 has been estimated at around $2.7 million. Despite low wages and large remittances to their families back home, Hawai'i's Japanese had private schools perpetuating their culture and taught in their language, attended by children during afternoons and weekends following their attendance at English-language schools certified as meeting the compulsory attendance law in conformity with the English-language law of 1896. Some of these Japanese schools were established by Christian missionaries of Japanese ancestry who had financial resources not available to the plantation workers. But if ethnic Hawaiians had wanted to preserve their culture and language by means of similar schools, there were plenty of wealthy ali'i who could have provided money as the Japanese Christian missionaries were doing; and the laws would have enabled the Hawaiians do so on the same basis that the Japanese actually did it.

Even within the official government-recognized schools, the law clearly does not prohibit Hawaiian language or other languages from being taught. The law merely says the language used for teaching all courses other than language courses shall be English. Indeed, the law explicitly states that language courses can be taught.

Here is some information about the laws of Hawai'i concerning Hawaiian language, taken from a sheet distributed by kumu hula John Lake in his Hawaiian culture classes. 1901 [note: 5 years after Hawaiian language was supposedly made "illegal"]: All laws become legally binding only when published in both an English daily newspaper and a Hawaiian weekly; 1913: Law requiring announcements relative to the sale of government land must appear in Hawaiian; 1913: $10,000 appropriated for publication of a Hawaiian dictionary; 1919: Law that Hawaiian shall be taught as a subject in all high schools and teachers' colleges; 1923: $2000 appropriated for writing and publishing textbooks in Hawaiian; 1935: Daily instruction of at least 10 minutes in Hawaiian conversation or writing required in elementary schools serving Hawaiian Homes children. Clearly, Hawaiian language was alive, and received government funding in the schools throughout the Territorial period.

The purpose of the 1896 law was both political and social, to promote the use of English as a universal language. Thus the barriers separating ethnic groups could be reduced and a growing feeling of social unity underlying cultural diversity could be enhanced. The government of Hawai'i was looking forward to U.S. annexation. English was already the primary language in Hawai'i's burgeoning local and foreign-trade economy, and in government operations. Many kanaka maoli parents both before and after the overthrow of the monarchy spoke Hawaiian between themselves but insisted that their children speak only English at home as well as at school. "Pidgin" (Hawaiian creole) was the language of the streets and the plantations -- a blending of Asian, European, and Hawaiian languages into a distinctively local way of communicating. But while pidgin helped people cross language barriers and gave them a convivial feeling of belonging to a "local" lifestyle, it lacked the ability to forumulate complex abstract concepts or precise legal contracts. Worst of all (or best of all!), it was incomprehensible to outsiders. Many Asian parents made decisions to remain in Hawai'i -- such decisions were made either explicitly when a first labor contract expired, or more gradually as time passed and they found themselves putting down roots. The primacy of English for business, law, and politics; and the formal attachment of Hawai'i to the United States through Annexation; made both Hawaiian and Asian parents recognize that the path to social and economic success for their children would increasingly be through English, not Hawaiian or pidgin or any Asian language.

The practical result was that use of Hawaiian language declined to the point where it was nearly extinct as a daily-use language by the time of statehood (except for its use in hula and other special cultural activities). Even many hula dancers memorized the Hawaiian language lyrics without understanding their meanings, just as some American-born opera singers memorize their Italian or German lines without understanding them. But now, thanks to a growing group of dedicated kanaka maoli and non-kanaka maoli, the language has been saved and is flourishing.

The use of Hawaiian language today carries political overtones, unlike the mere fact of using other langauges in the homelands of those languages. Some kanaka maoli speakers use Hawaiian language as a political weapon to assert cultural hegemony, in somewhat the same way as a Roman Catholic priest 50 years ago might use Latin in church (even knowing that hardly anybody understood it). This use of Hawaiian language adds a sense of mysterious spiritual power and is an implied assertion of superiority. For example, public chants and prayers are given at the opening of political rallies for Hawaiian sovereignty, or at the opening of formal hearings by the Army to take testimony regarding military use of Makua Valley. Sometimes those who offer the chants or prayers, or sing along, might not know what they mean, but have merely memorized them to make a political point. People with no Hawaiian blood are generally encouraged to learn Hawaiian language, but only up to a certain limit. If someone who has no Hawaiian blood uses Hawaiian language phrases or even longer passages to make public statements in opposition to Hawaiian sovereignty, that is considered insulting and grossly improper. Some kanaka maoli who have not yet learned the language but are active in the sovereignty movement are extremely resentful or even angry toward non-kanaka maoli who do use the language, even just to give a sentence or two of friendly greeting or to express thanks for a favor. "How dare you speak my native language to me when I don't know my language because your people oppressed my ancestors and suppressed our language!"

A scholarly study of the history of language in Hawai'i was done as a dissertation by John Reinecke at the University of Hawai'i in 1935. The dissertation was improved and published as a book. John E. Reinecke, "Language and Dialect in Hawaii: A Sociolinguistic History to 1935." Edited by Stanley M. Tsuzaki. Honolulu: Universiry of Hawaii Press, 1969. Reprinted 1988. Paperback edition February, 1995.

Mr. Reinecke says the shift from Hawaiian language to English began under the Kingdom and was very far along by the time the monarchy was overthrown (see Table 8, pp. 70-73). Reinecke's chart summarizes the number of schools and students operating in Hawaiian and English based on Education Department reports from 1847 to 1902. The number of students in Hawaiian language schools falls continuously through this period while the number in English-language schools rises; likewise the numbers of schools operating in the respective languages. The number of students in Hawaiian-language schools dropped below 50% in 1881 or 1882. By 1892 (the year before the overthrow), only 5.2% of students were in Hawaiian language schools and there were only 28 such schools in the Kingdom; at the same time, 94.8% of students were in the 140 English-language schools.

According to Reinecke, there were several factors accounting for this switch from Hawaiian to English as the favored language even before the overthrow.

(A) as early as the late 1840s, the Kingdom government had a policy of gradually increasing education in English because the government saw that as the more valuable language for developing the country in the long run (see factor C). They probably figured that parents could teach their children Hawaiian at home but the schools should teach English as much as possible to open up opportunities.

(B) English language schools were considered better schools by almost everyone and initially charged extra while the Hawaiian schools were free. A lawsuit was actually filed over the the extra charge for English-language schools! Naone v. Thurston 1 Haw. 220 (1856) Asa Thurston (father of revolutionary Lorrin Thurston) unsuccessfully argued that he was being discriminated against by having to pay about $5 extra to educate little Lorrin and his siblings). Later, when the government got enough tax revenue to be able to afford to stop charging extra, people of all ethnicities (including Hawaiian) rapidly shifted their children to the free English language schools. But even before the extra fee was abolished, people of all ethnicities, including Native Hawaiians, were switching schools in favor of the English-language ones as soon as they could afford to pay the extra fee.

(C) Immigrants to the Kingdom, especially the Portuguese who brought their families, wanted to have their children educated in English. The Portuguese had no cultural reasons to prefer one language foreign to themselves (English) over another language foreign to themselves (Hawaiian); but all the practical reasons favored learning English rather than Hawaiian. English was already the language of business in Hawaii and certainly of the international business in the Pacific at that time. English was increasingly the language of government, even before Annexation. English (at least pidgin English) was the lingua franca that allowed immigrant Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Filipinos (who started coming soon after 1900), etc. to communicate with each other; so the better their children learned English the more opportunities they would have. There may be a few immigrant families who chose Hawaiian as the language for their children's assimilation -- I know of one case where a Japanese man married a Portuguese woman, started a rice farm, and the entire family spoke Hawaiian as their primary language in their home in Wai'alua, O'ahu. But "the exception proves the rule": most immigrant families chose English as their language of assimilation to Hawai'i, because English was clearly becoming the language for economic and social advancement.

(D) Reinecke also stresses another factor in the shift from Hawaiian to English: intermarriage between Hawaiians and others. The hapa (mixed-race) Hawaiian children picked up English rather than learning either or both of their parents' original languages fluently. Reinecke cites statistics showing that, at any given time, hapa-Hawaiians were more fluent in English and relatively less fluent in Hawaiian than "pure" Hawaiians. One explanation might be that at any given time the median age of hapa people is lower than the median age of "pure" anything because intermarriages have become steadily more common, leading to a growing number of hapa children in each new generation. Since the overall trend is towards English, English fluency is positively correlated with youth.

Sovereignty activists who don't know John Reinecke's background might routinely try to discredit his findings by accusing him of being a running dog of the haole capitalist imperialists -- the activists like to attack opposing scholars this way. But Reinecke was an activist in the union movement in Hawaii, accused of being a Communist in the late 40s and early 50s. He was a school teacher for decades and active in Democratic party politics. His wife, a Nisei (second-generation Japanese), was also active in political life, and was a highly respected schoolteacher. Mr. Reinecke's approach is scholarly and he seems to have been trying to show that public education was used intentionally to level out the economic and ethnic hierarchy of plantation-era Hawaii. For example, he spends considerable effort looking at the ways the varieties of pidgin and standard English were used as social class markers. If everyone were to grow up speaking good English, such markers would vanish and it would be harder to discriminate against people of lower ethnic or social class by immediately recognizing their dialect.

Another book confirms that the transition from Hawaiian to English as the medium of instruction was well underway voluntarily by the midpoint of the Kingdom, and was nearly complete before the monarchy was overthrown. See Albert J. Schutz, "The Voices of Eden: A History of Hawaiian Language Studies," (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994). It was an official policy of the Kingdom's schools to promote English-language instruction, because learning English opened the door to the outside world both commercially and culturally. Many ethnic Hawaiian families preferred English-language schools to Hawaiian language schools. As first-gereration Asian immigrants began producing children who reached school age, especially after the overthrow and during the Territorial period, very few of them showed any interest in Hawaiian language and were glad to have their children educated through the medium of English. During the Territorial period, Hawaiian language was taught as a second language in the public schools, and enrollments in Hawaiian were greater than enrollments in Japanese. Hawaiian language studies at the University of Hawai'i go as far back as the 1920s. By contrast, Kamehameha School (exclusively for ethnic Hawaiian children by a policy decision of its board of trustees) prohibited Hawaiian language from 1887 up to about 1923, when the school began teaching Hawaiian as a second language. And here it's worthwhile to note that Kamehameha was teaching Hawaiian as a second language at a time when today's sovereignty activists like to say that the 1896 English-language law would ban Hawaiian language in any school, public or private.

Helena G. Allen published a book whose title clearly shows her political views: "The Betrayal of Liliuokalani" (Glendale CA, Arthur H. Clark Co., 1982). On page 111 she says the following in the context of discussing Lot Kamerhameha V and the early 1860s: "Verbal battles were raging throughout the islands of whether Hawaii should be bilingual or only English speaking. There was no thought that the language, official or otherwise, should be Hawaiian. With the loss of a language, as [Lorenzo] Lyons pointed out, comes the destruction of cultural connotations and denotations. It was, however, becoming fairly obvious that a non-English speaking person could have no important government post. The country people began to cry to have English taught in their schools, 'Or,' they said, 'we will be nothing.'"

By the time of the overthrow, English was well-established as the standard language of the Kingdom for use in government and business. Throughout Kalakaua's reign, the official record of proceedings of the Legislature was published twice in the same book: English and Hawaiian. Queen Lili'uokalani herself had only one time in her career when she gave a speech at the opening of the Legislature, and she used English to give her speech even though most of the Nobles and Representatives were native Hawaiian. Here's what Helena Allen says on pp. 269-270:

"On May 28, 1892, Hawaii's legislature opened with fanfare as carriages rolled through the gates of Aliiolani Hale, past the black and gold statue of the first Kamehameha, the Queen's Household Guards in battle array presented arms, and opposite them across the drive the Royal Hawaiian Band played one lively tune after another. Indoors there were kahilis and great boquets of lilies. There were special seats for the dignitaries, and the throne was draped with a golden feather cloak. When the Queen's coach left Iolani Palace, a salute resounded from Punchbowl, and when, drawn by a span of black horses, it arrived at Ali'olani's [sic] entrance, the band swung majestically into "Hawaii Pono'i." This was Liliuokalani's first legislature, though she had been queen a year and four months; for the sessions were biennial. It was also her last, ... With grace and spirit, LILIUOKALANI DELIVERED HER ADDRESS, IN ENGLISH, ..." [emphasis Conklin's]

As Reinecke, Schutz, and others have pointed out, it was the official policy of the Kingdom government to strongly favor English language; and English was already established as the medium of instruction in 95% of the Kingdom government schools by1892. That was a consistent policy freely adopted by the sovereign native Kings exercising self-determination on behalf of their people.

A remarkable booklet "Ha'ilono 2008" was produced by the staff of the Ho'olaupa'i Hawaiian Newspaper project under the auspices of Bishop Museum. On page 20 the booklet says: "We often hear that the decline of the Hawaiian language resulted from a law banning its use, passed by the Republic of Hawaii in 1896. The newspapers, however, tell a different story. In 1845, S.M. Kamakau petitions Kamehameha III, questioning the merit of appointing non-native over native Hawaiians for government positions. Kauikeaouli responds that he sees the importance of the old ways, but times are changing and he needs in office people trained in the Western ways to deal with foreign nations. 'I however hope that the time will come when these positions will be again placed among our own, once the young chiefs are educated.' To the right [photo of newspaper clipping from Ka Hoku O Ka Pakipika, May 8, 1862, p.2], Kamehameha IV addresses the legislature in 1862, '... I stated previously my opinion to you, that it is important to change all Hawaii's schools to English speaking schools, and I once again put this forth to all.' Wai'ohinu, in 1875, sees English as the way for Hawaii to hold on to its independence. He states, 'Kamehameha III was greatly admired for his establishing the English language schools for the young chiefs to learn English. His foresight that English would be the means through which we would survive, was like that of a prophet."

The document below from 1882 makes that policy of using English language as the medium of instruction crystal clear. It explicitly says "... it will be advisable to make it a rule that in all select schools, taught in English, the pupils be forbidden during school hours from conversing in Hawaiian. It is thought that the enforcement of such a rule would be of great value in aiding the scholars to master and familiarize themselves with the strange tongue." Thus, if forbidding children to speak Hawaiian in school is regarded as an act of suppressing Hawaiian language, then it was King Kalakaua himself who was already suppressing Hawaiian language in 1882!

This material is taken from Hawaii. Kingdom, Legislature. Education Committee — Report of the Committee on Public Education. [Honolulu, 1882], Archives of Hawai'i.

"The subject of English-language instruction is, in fact, central to this report. The committee express general approval of a plan to introduce English into all the schools, but with some reservations: "It is a good measure, doubtless, to turn all our schools into English schools, and yet it is contrary to rule and precedent in any nation to bring in a new and strange language, and proceed to force it upon the young, in order that they shall forget their mother tongue. A feeling of regret arises in considering the possibility that we, and the nation of the future, are to talk only in English, and that we are no more to hear the familiar accents and smooth-flowing speech that has come down to us from our ancestors." With respect to English instruction in government select schools, "the committee beg to say that in their opinion it will be advisable to make it a rule that in all select schools, taught in English, the pupils be forbidden during school hours from conversing in Hawaiian. It is thought that the enforcement of such a rule would be of great value in aiding the scholars to master and familiarize themselves with the strange tongue."

Independence activist Keanu Sai, in his blog entry for November 27, 2013, regarding the Ka La Ku'oko'a (Independence Day) holiday of the Kingdom, cites a detailed description of what happened in 1843. Sai says "Here follows the story of this momentous event from the Hawaiian Kingdom Board of Education history textbook titled "A Brief History of the Hawaiian People" published in 1891." The story about 1843, and indeed the entire textbook published in 1891 by order of the board of education of the Kingdom of Hawaii, were printed in English. Furthermore the vocabulary and complexity of the English were quite advanced. For example: "Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

Accordingly Sir George Simpson, Haalilio, the king's secretary, and Mr. Richards were appointed joint ministers-plenipotentiary to the three powers on the 8th of April, 1842. Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king." Thus we see further corroboration that English was already the language of instruction in the government schools of the Kingdom before the revolution of 1893. Sai's blog entry providing the textbook story is at

http://hawaiiankingdom.org/blog/?p=1004

Those who think that the English-only school law of 1896 killed or suppressed Hawaiian language should consider this: Today's Hawaiian immersion kids speak only Hawaiian in school. Do they grow up not also speaking English? Of course not. They learn English spotaneously because English is the dominant language of everyday life. So back in the day, the English-only rule for schools could never have killed Hawaiian language unless that language was already dying from natural causes. If Hawaiian had been the dominant language at home and on the streets when this law was passed in 1896, then the kids would have learned Hawaiian even though it was not used in school; in the same way that kids in today's Hawaiian immersion schools learn English even though the rule in their schools is Hawaiian-only.

Hawaiian language was not illegal and was, in fact, flourishing during the early Territorial period, as shown by the following short items taken from the indicated pages of Rich Budnick, "Hawaii's Forgotten History 1900-1999" (Honolulu: Aloha Press, 2005).

p. 18: 4/9/03: Territorial Legislature overrides Governor Sanford Dole's veto of a joint resolution asking Congress to allow Hawaiian and English to be Hawaii's official languages. Legislators had been speaking and printing bills in both languages. Opponents of using the Hawaiian language point out that statehood has been delayed several decades for New Mexico and Arizona because they speak Spanish and English.

p.20 12/12/03: Pacific Commercial Advertiser says the 1903 Legislature spent $20,000 to interpret, translate and print bills in Hawaiian, although federal law requires English only.

p. 26: 4/05/07: Governor George Carter signs a law to require English as the basis of teaching in all public and private schools

p. 32: 2/17/11: Territorial House votes not to receive bills from the Senate unless they are translated into Hawaiian.

p. 61: 5/10/28: A Hawaiian language weekly newspaper is established, KE ALAKAI O HAWAI'I. It continues until 1939.

It's interesting to imagine what would have happened if current ideas of ethnic nationalism, multiculturalism and bilingual education had been available to the plantation operators in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They had a conscious policy towards their workers of "divide and rule" and were distinctly unenthusiastic about giving the workers' children enough education to do more than chop sugarcane. The plantation operators got overruled by government officials who insisted everyone was entitled to an education and all those children should be taught to be good American citizens.

The plantation operators' policy of divide-and-rule is also more complex and less divisive than commonly ascribed to it. For example, it made sense to provide housing for the workers that grouped them in "camps" according to ethnicity and native language, where they could feel at home with each other. It also made sense to organize work-gangs according to language and culture, so workers could communicate easily and work efficiently and cooperatively. Due to major differences in dialect and culture between different prefectures (regions comparable to American states) in Japan, the Japanese workers on Hawai'i's plantations were often further sub-grouped by prefecture for plantation housing and work gangs.

If the plantation operators were truly determined to pursue a divide-and-rule strategy, and if they had the advantage of today's theories of "multiculturalism," they might have responded that they wanted to respect the ethnic heritage of every nationality by ensuring that each group had its own separate school system operating in its own language (Hawaiian, Chinese, Japanese, English, etc.). That would have ensured that only the haole children would have gotten English educations in segregated schools that equipped them for the management jobs, top government jobs and international trade. It would have made sure that everyone else was on track for a dead-end job chopping sugar cane. And it would be nearly impossible to organize a union if the workers couldn't talk to each other. But that segregated outcome was prevented by hundreds of now-anonymous school teachers who insisted that every one of their pupils was a 100% American who had a right (and duty) to learn English and get a good education. And that outcome was also prevented by the 1896 law that required all schoolchildren to learn English as the medium of instruction in the "compulsory attendance law" schools, both public and private.

One final point regarding the claim that even private schools were prohibited from using Hawaiian language as the medium of instruction during the Territorial period. In Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923) the US Supreme Court held that the Constitution does not allow a state to forbid private schools in languages other than English. The case involved a ban prompted by anti-German feelings during World War I. Hawaii's government could not have made teaching in Hawaiian illegal even if it had wanted to.

The Hawaiian grievance industry likes to portray the Republic and Territory laws favoring English as being intended to suppress Hawaiian language and culture. But the Hawaiian grievance industry, perhaps intentionally, is overlooking the fact that the primary purpose of the pro-English laws was directed against Japanese, Chinese, and Portuguese languages rather than the Hawaiian language. The largest number of children speaking something other than English in the home were Japanese, not native Hawaiians. Remember that by 1892 only five per cent of all the government schools were still using Hawaiian as the language of instruction.

There was a very aggressive effort by Japanese parents to preserve Japanese language and culture for their children, including many private after-school and weekend academies where Japanese was the language of instruction. The 1896 law of the Territory requiring English as the medium of instruction was probably written with Japanese language in mind, because of the tens of thousands of Japanese families recruited to the sugar plantations. Certainly by the early Territorial period it became clear that the government of Hawai'i was struggling mightily to assimilate ethnic Japanese children who were born in Hawai'i as American citizens. The situation regarding assimilation of Japanese to English language in Hawai'i of the early 1900s was similar to the situation regarding the assimilation of Mexican illegal immigrants to English language in California of the early 2000s.

Here are a few items taken from the indicated pages of Rich Budnick, "Hawaii's Forgotten History 1900-1999" (Honolulu: Aloha Press, 2005).

p.22: 4/08/04: Reverend Takie Okumura establishes Makiki Christian Church with 24 members. Rev. Okumura is warmly supported by Hawaii's Caucasian elite, yet many Japanese Buddhists reject him. He supports "Americanism" values ... supports Hawaii's 1920 foreign language law because he wants to eliminate American distrust of Japanese. He established the first Japanese YMCA on April 28, 1900, Hawaii's first Japanese language school, Central Institute on April 6, 1896, and opened a Boy's Home.

p. 26: 4/05/07: Governor George Carter signs a law to require English as the basis of teaching in all public and private schools

p. 49: 11/24/20: Governor Charles McCarthy signs a law to require the Department of Public Instruction to regulate private foreign language schools, limit instruction to one hour per day, and to issue licenses to such schools and their teachers. All foreign language school teachers must pass an English test and possess the "ideals of democracy ... promote Americanism." There are 163 such schools -- 9 Korean, 7 Chinese and 147 Japanese -- with 300 teachers and 20,000 students. Many schools file a lawsuit to protest the law.

p. 52: 10/13/22: Governor Wallace Farrington says Hawaii's AJAs who "erect a little Japan" with foreign language schools will be confronted with "an increasing feeling of suspicion and distrust, born of the fact that the Americans feel that their confidence and good will have been abused."

p. 58: 12/31/26: Superintendent of Public Instruction reports that a majority of Hawaii's 29,546 Asian students attending foreign language schools are U.S. citizens, not aliens.

p. 58: 2/21/27: The U.S. Supreme Court rules unanimously that Hawaii's 1920, 1923, and 1925 laws regulating Japanese language schools are unconstitutional.

p. 58: 4/23/27: Goveror Wallace Farrington sings a law to allow the Department of Public Instruction to establish English standard schools ... Governor Lawrence Judd signs a similar law on April 30, 1931. ... By 1947, a majority of the standard school students are AJAs.

Reinecke, on pages 127-129, mentions that despite efforts by the Territorial government to suppress Japanese-language schools, there were a great many such schools. These Japanese schools, of course, were not certified by the government of Hawai'i as meeting the compulsory attendance laws. Children of Japanese ethnicity went to learn Japanese language and culture at these private schools after already spending the day in the regular government-certified English-language schools. About 5 out of every 6 ethnic Japanese children in Hawai'i attended these after-school Japanese language and culture schools -- In 1931 the figure was 87%.

The Territory of Hawai'i continued the policy of the Kingdom and Republic, to establish English as the universal language spoken by all Hawai'i's people. Part of that policy was to severely regulate and discourage all the private schools that were using Asian languages as the medium of instruction to perpetuate various cultures. Most of these after-school private academies were Japanese. According to Rich Budnick, "Hawaii's Forgotten History", p49, on November 24, 1920 "Governor Charles McCarthy signed a law to require the Dept of Public Instruction to regulate private foreign language schools, limit instruction to one hour per day and to issue licenses to such schools and their teachers. All foreign language school teachers must pass an English test and possess "the ideals of democracy…promote Americanism." There are 163 such schools - 9 Korean, 7 Chinese and 147 Japanese - with 300 teachers and 20,000 students. Many schools file a lawsuit to protest the law." The policy of the Territorial government was clearly to establish English as the iniversal language of Hawai'i's multiethnic society; and in the process the government attempted to "suppress" the Asian languages while not suppressing Hawaiian language at all (mostly because ethnic Hawaiians themselves had already suppressed Hawaiian language quite effectively in favor of English within their own families).

The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which followed the decision in Meyer v. Nebraska and affirmed the 9th Circuit's strongly worded opinion upholding an injunction against the Territory's statute. Interestingly, the statute had not applied to Hawaiian language schools because Hawaiian, like English, was favored. The result was very strong legal support for the concept that there is a right under the Constitution for parents to have their children learn whatever language and culture they wish, so long as they do so in addition to attending the government-certified (public or private) English-language schools. The 9th Circuit Court rejected the Territory's argument that it had to severely limit Japanese language schools in order to Americanize Japanese-American children, saying: "You cannot make good citizens by oppression or by a denial of constitutional rights." 11 F.2d at 714. It went on to quote from the Supreme Court's Meyer case: "The protection of the Constitution extends to all; to those who speak other languages, as well as those born with English on the tongue."

The legal citations regarding the statute banning Japanese language schools, and the lawsuit against that statute, include the following: The Supreme Court case was: Farrington v. Tokushige, 273 U.S. 284 (1927), affirming the 9th Circuit decision Farrington v. Tokushige, 11 F.2d 710 (9th Cir. 1926). On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The original suit in the U.S. District Court in Honolulu was by T. Tokushige and others against Wallace R. Farrington, Governor of the Territory of Hawaii, and others. The 9th Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the trial court (U.S. District Court in Honolulu) did not abuse its discretion in granting temporary injunction forbidding an attempt to enforce the provisions of Laws Hawaii Sp. Sess. 1920, Act 30, as amended by Laws Hawaii 1923, Act 171, and Laws Hawaii 1925, Act 152, regulating foreign language schools and teachers thereof. Constitutional right of pupils to acquire knowledge of foreign language and right of others to teach it is beyond question (Rev.Laws Hawaii 1925, § § 390- 399).

-----------

In July 2005 a newly published book included a substantial amount of information about the 1919 to 1927 effort by the Territorial government, and by the U.S. Government in California and Washington, to abolish Japanese language schools.

http://www.uhpress.hawaii.edu/cart/shopcore/?db_name=uhpress&page=shop/flypage&product_id=4131&category_id=b3e6237d1b1b3b8594488ed1c40d0dfb&PHPSESSID=7c04589b07c0d8ee12b08c14a9ba9fb4

Noriko Asato, "Teaching Mikadoism: The Attack on Japanese Language Schools in Hawaii, California, and Washington, 1919-1927" University of Hawaii Press, July 2005, 192 pages.

Hawaii sugar plantation managers endorsed Japanese language schools but, after witnessing the assertive role of Japanese in the 1920 labor strike, they joined public school educators and the Office of Naval Intelligence in labeling them anti-American and urged their suppression. Thus the "Japanese language school problem" became a means of controlling Hawaii's largest ethnic group. The debate quickly surfaced in California and Washington, where powerful activists sought to curb Japanese immigration and economic advancement. Language schools were accused of indoctrinating Mikadoism to Japanese American children as part of Japan's plan to colonize the United States.

Previously unexamined archival documents and oral history interviews highlight Japanese immigrants' resistance and their efforts to foster traditional Japanese values in their American children. They also reveal complex fissures of class and religion within the Japanese communities themselves. The author's comparative analysis of the Japanese communities in Hawaii, California, and Washington presents a clear picture of what historian Yuji Ichioka called the "distinctive histories" as well as the shared experiences of Japanese Americans.

Noriko Asato is associate professor in the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

---------------

** Thanks to the late Patrick Hanifin, esq., for legal research; and to Wendell Marumoto for historical information and insights regarding Japanese immigration and assimilation to Hawai'i.

-------------------

Postscript #1: On April 29, 2004 the Honolulu Advertiser published a short notice regarding the 120th anniversary celebration of Kuhio Elementary School. This item is noteworthy because it mentions that the school was founded as a government school in 1884 using Hawaiian language as the medium of instruction, and then changed to English as the medium of instruction just four years later, in 1888 (all during the reign of King Kalakaua).

http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2004/Apr/29/ln/ln45a.html

Kuhio Elementary observes 120th

Kuhio Elementary School will celebrate its 120th anniversary with a lu'au and fair at the school from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. May 15.

The school was founded in 1884 as Kamo'ili'ili School and renamed Mo'ili'ili School in 1888 when it converted from a Hawaiian language to English language government school. It was renamed again in 1923 for Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana'ole, who died the previous year.

The event will include entertainment, games, prizes and baked goods.

Presale tickets for the lu'au plate are $12 for adults and $8 for children.

For more information, call 973-0085.

-------------------

Postscript #2: On August 2, 2005 the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals handed down a ruling that the racially exclusionary admissions policy of Kamehameha Schools is illegal. The 3-judge Kamehameha panel made the following observation on page 6 of the pdf copy of the ruling at:

https://www.angelfire.com/hi5/bigfiles3/Kamehameha9thCircuit070205.pdf

"As the Schools' 1885 Prospectus observed: 'The noble minded Hawaiian chiefess who endowed the Kamehameha Schools, put no limitations of race or condition on her general bequest. Instruction will be given only in English language, but The Schools will be opened to all nationalities.'"

So here we have the most wealthy and powerful native Hawaiian chiefess, able to set up her school to use whatever language she preferred. And here we have the Trustees she appointed, opening a school 8 years before the overthrow of the monarchy, and two years before the "Bayonet Constitution," when the Hawaiian "merrie monarch" King Kalakaua ruled and was reviving hula and Hawaiian language. And that school is conducting its courses solely in English language. That was clearly a free choice, and supports the findings of this webpage that Hawaiian language went into a coma due to natural causes and not because of suppression.

-------------------

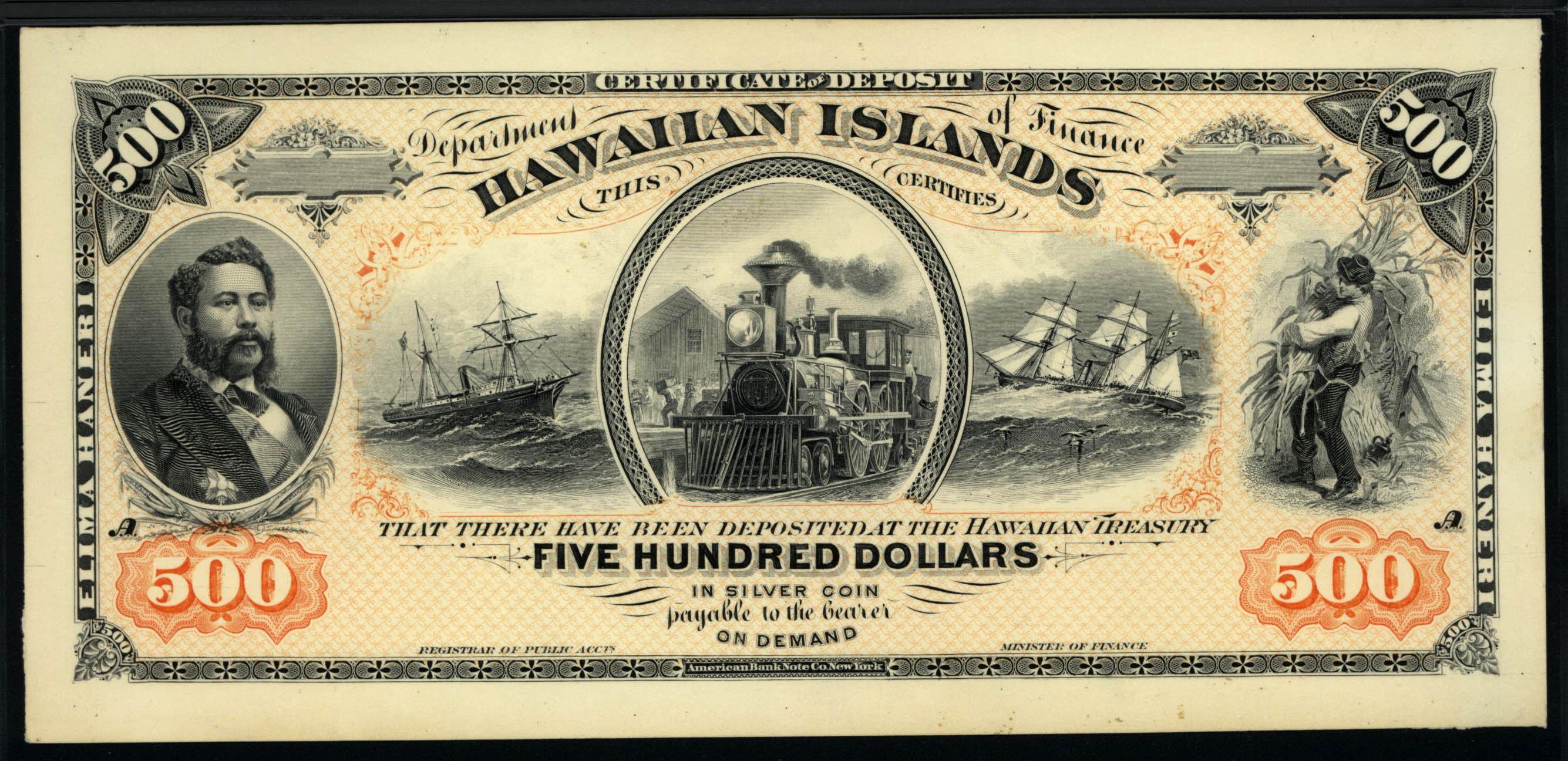

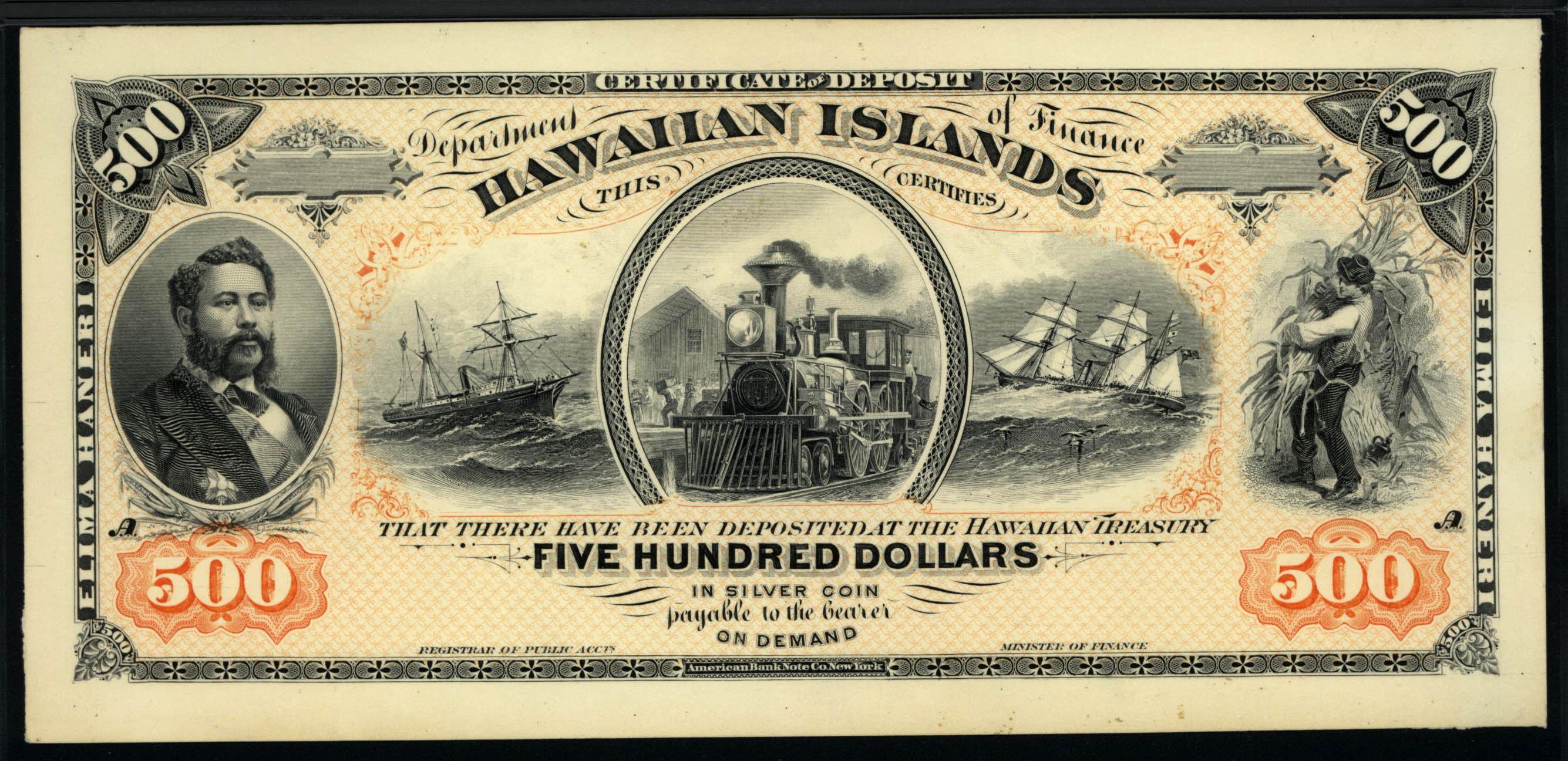

Postscript #3: Regarding the use of English as the overwhelmingly predominant language on Hawaiian Kingdom banknotes and coins.

In 2010 a rare $500 Hawaiian Kingdom banknote from 1879 was offered at auction. Thus a photo of it became available. Remember that King Kalakaua was elected in 1874, so the banknote was printed at a time when the culture was being revived and the native monarch's power was not yet challenged. The ONLY Hawaiian language words on the banknote are the two words "elima haneri" appearing in (relatively) small print at the left and right margins. Here's the photo (scroll left and right to see it all):

In 2009 a coin collection was auctioned, including the following Hawaiian Kingdom coin dated 1883. The front of the coin features King Kalakaua, and the only words appearing on the front of the coin are: "Kalakaua I King of Hawaii"

In June 2017 a reader of this webpage kindly sent a photo of the back side of the Kalakaua quarter, which is entirely in Hawaiian language: first the motto of the Kingdom "Ua mau ke ea o ka aina i ka pono" [Diacritical marks had not yet been invented for the Hawaiian language back then.]; and at the bottom "Hapaha" [which means "quarter" as is confirmed by the fraction 1/4 at the left of the crest]. Presumably the letter "D" at the right of the crest is related to the fraction 1/4 and refers to the word "Dala" which means "dollar"; so the coin's value is 1/4 dollar.

On March 24, 2006 the Honolulu Advertiser published a news report about an auction which sold extremely valuable historical items from the Damon Estate. One of those items was a ten-dollar bill printed in the year 1880 -- it was the first bill of the $10 dollar denomination printed for the Kingdom of Hawai'i, during the reign of King Kalakaua, and has serial number 1. A photograph of the bill was published as part of the newspaper article. It is not easy to read the writing on the bill in the Advertiser webpage copy of the newspaper article; but the bill's writing was easily readable in the physical copy of the newspaper. EVERY word or phrase on the 1880 $10 bill is in English, except for a small-size Hawaiian word "Umi" [ten] centered along the left and right-hand edges. The largest-size print is centered at the top and says "Hawaiian Islands". Above that is "Department of Finance." The top margin says "Certificate of Deposit" and the entire border around all four edges has alternating "ten 10 ten 10" etc. except for the one "umi" on the left and right edges. The bill says "This certifies that there have been deposited at the Hawaiian treasury ten dollars in silver coin payable to the bearer on demand. On the bottom left is the signature "Godfrey Brown" and his title "Registrar of Public Accts". On the bottom right is a signature that appears to be "W. Kuaia" and his title "Minister of Finance". Thus, out of a large number of words and phrases on the front of the ten-dollar Kingdom banknote of 1880, every one of them is in English except the two small-size words "umi". The entire article, including the photo of the banknote, is at:

http://www.honoluluadvertiser.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20060324/NEWS01/603240354/1190/NEWS

--------------

Postscript #4, added April 2, 2012. A book published in 2011, "Pacific Gibraltar", provides detailed information about Japanese immigration to Hawaii during the 1890s, and the fact that it was of great concern to both U.S. and Hawaiian government officials. The book says Japanese immigration was the main reason why annexation was finally consummated in 1898. The Hawaii census of 1896 showed Japanese were already the largest ethnic group in Hawaii and heading toward becoming a majority. The government of Japan was demanding they should have voting rights, and Japan had been sending warships to Hawaii to oppose annexation and to back up demands for voting rights. The language law was enacted on June 8, 1896. The "Pacific Gibraltar" book provides plenty of information that would support the view that the language law was directed at Asians, and especially Japanese, rather than at Hawaiians. See a major book review with lengthy quotes, at

https://www.angelfire.com/big09/PacificGibraltarBookReview.html

-------------

Postscript #5, added May 26, 2013: Here's a republished newspaper article from 1931, which was deep into the time period when Hawaiian language was supposedly "illegal." It's significant for two reasons: it shows that in 1931 a state Senator gave a speech in Hawaiian language and was neither arrested nor in any way penalized for speaking Hawaiian in public; and it shows that there was only one Hawaiian-language speech in the legislature that year even though Hawaiian language could have been used as often as anyone wished.

http://www.staradvertiser.com/editorialspremium/20130526__Senator_Desha_claims_his_speech_in_Hawaiian_was_misinterpreted.html?id=208917981

Honolulu Star-Advertiser, Sunday May 26, 2013, Page F3

BACK IN THE DAY

Every Sunday, “Back in the Day” looks at an article that ran on this date in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. The items are verbatim, so don’t blame us today for yesteryear’s bad grammar.

Senator Desha Claims His Speech In Hawaiian Was Misinterpreted

MAY 26, 1931

His Attack on Governor Was Free of Personal Element and Accused Judd of Ignoring the Hawaiians, Not of Being Their Enemy

That his sensational speech in Hawaii, in which he took occasion to criticize the policies of Governor Lawrence M. Judd with regard to rehabilitation and the Hawaiian race, was misinterpreted in part is the claim of Senator Stephen L. Desha, Sr.

Senator Desha said his attack on the governor was free from personal element and that he and the governor are the best of friends despite the senator's disagreement on administration policies.

"I did not say that the governor is the enemy of the Hawaiians," Senator Desha explained. "What I said was that he is ignoring them."

The senator said that too few Hawaiians are being appointed to boards, commissions or government posts in the territory.

He charged that the administration is not in sympathy with the rehabilitation project and that those in charge of carrying out the project are slowly killing it. This was the keynote of his talk.

He criticized the appointments of the administration with regard to rehabilitation, claiming that the appointees do not understand the purpose of the scheme.

He said there is vast discontent among Hawaiians throughout the territory, especially because of a policy of the Hawaiian Homes commission which precludes them from doing any work except on the lands alloted them.

The senator asked that accounts of his talk be corrected in so far as it was intimated that the governor was an enemy of the Hawaiians. He said he intended to point out only a lack of confidence on the part of the administration which, he claims, is revealed by the tendency of the administration to ignore the Hawaiians.

The senator aid he was not apologizing for his talk or retracting it, but was explaining the correct significance of his utterances.

Senator Desha talked for 40 minutes in Hawaiian and at times he exhibited great emotion. It was the only talk of any length he gave in the recent session of the legislature and the only speech given in Hawaiian during the entire session.

===============

(3) English has become the dominant language throughout the world in international venues, and there are some multi-ethnic nations today where government imposes a "major" foreign language on all citizens by consent of all ethnicities to facilitate communication.

This webpage has explored the claim that Hawaiian language was made illegal, or suppressed, for the purpose of imposing English upon an unwilling population. Accordingly this webpage has focused on events in Hawaii from 1820 to 1950, regarding only English and Hawaiian languages. But some other topics may also be of tangential interest to readers of this webpage. (a) English has become the primary language for international diplomacy and commerce, by voluntary choice of people of all nations. So it turns out that ethnic Hawaiians made a wise choice to abandon Hawaiian in favor of English (and not some other language such as French, German, Russian, Japanese, or Cantonese, any of which would have been pleasing to some portions of the population). Seeing how people throughout the world seem to prefer English as a universal language makes it easier to understand why Hawaiians felt that way. (b) There are indeed a few places in the modern world where indigenous or local languages are being banned or suppressed by government action for the purpose of forcing people to adopt one of the world's "major" languages as a common language in a multiracial, multicultural, multilingual society. Perhaps the best example from the 20th Century was the Soviet Union, where every school forced all children to learn Russian and use it as the language of instruction even though there were over a hundred nationalities, ethnic groups, and languages incorporated (involuntarily) into the Soviet empire. Looking at such situations makes it easy to see that Hawaiians did not undergo such oppression. Looking at situations where minorities voluntarily adopt a foreign language also makes it easy to see that in some multilingual societies the need to adopt a language everyone must speak makes people willing to master a foreign language they never knew before.

--------------

(a) English has become the dominant language worldwide

For many years English has been increasingly the language preferred throughout the world when different nations, corporations, or individuals who normally speak different languages come together for meetings. Air traffic controllers for international flights have used English as their only language for over a century throughout the world; thus, pilots from all nations must speak English when flying outside their own nations. Of course the United Nations has professional interpreters who provide instant translations through headphones so that everyone attending meetings of the Security Council or General Assembly can listen to speeches by choosing among several "official languages" of the U.N. But very few international meetings operate that way. People who normally speak French, German, Russian, etc. voluntarily use English routinely in international venues since they know that by doing so they will be understood.

English has become accepted as the preferred language for many reasons, including many decades of military, economic, political, and cultural dominance by English-speaking nations -- now primarily the United States, but also previously Britain and its (former) colonies India, Canada, Australia, Hong Kong, etc. Some nations (like France) became so concerned about the need to protect their cultures and languages that they passed laws prohibiting the use of English on radio, television, and newspapers; and banning English loan-words.

Following are some articles from recent magazines and newspapers showing that English is being voluntarily adopted as the "lingua franca" for international organizations and business transactions, even when the majority of participants do not speak English as their native tongue.

------------

http://www.economist.com/world/europe/displaystory.cfm?story_id=9512531

The Economist (London), July 19, 2007 (from the print edition)

Linguistic follies

by Peter Schrank

The economic consequences of the rise of English

IN RECENT years Brussels has been a fine place to observe the irresistible rise of English as Europe's lingua franca. For native speakers of English who are lazy about learning languages (yes, they exist), Brussels has become an embarrassingly easy place to work or visit. English is increasingly audible and visible in this scruffily charming Belgian city, and frankly rampant in the concrete-and-glass European quarter. Now, however, signs of a backlash are building. This is not based on sentiment, but on chewy points of economic efficiency and political fairness. And in a neat coincidence, Brussels is again a good place to watch the backlash develop.

Start in the European district, where to the sound of much grinding of French and German teeth, the expansion of the European Union has left English not just edging ahead of the two other working languages, but in a position of utter dominance. The union now boasts 27 members and 23 official languages, but the result has been the opposite of a new tower of Babel. Only grand meetings boast interpreters. At lower levels, it turns out, when you put officials from Berlin, Bratislava, Bucharest and Budapest in the same room, English is by far the easiest option.

Is this good for Europe? It feels efficient, but being a native English-speaker also seems to many to confer an unfair advantage. It is far easier to argue a point in your mother tongue. It is also hard work for even the best non-native speakers to understand other non-native versions of English, whereas it is no great strain for the British or Irish to decipher the various accents.

François Grin, a Swiss economist, argues that Britain enjoys hidden transfers from its neighbours worth billions of euros a year, thanks to the English language. He offers several reasons, starting with spending in Britain on language teaching in schools, which is proportionately lower than in France or Switzerland, say. To add insult to injury, Britain profits from teaching English to foreigners. “Elevating one language to a position of dominance is tantamount to giving a huge handout to the country or countries that use it as a native language,” he insists.

What about the Europe outside the bubble of EU politics? Surely the rise of English as a universal second language is good for business? Perhaps, but even here a backlash is starting, led by linguists with close ties to European institutions and governments. They argue that the rush to learn English can sometimes hurt business by making it harder to find any staff who are willing to master less glamorous European languages.

English is all very well for globe-spanning deals, suggests Hugo Baetens Beardsmore, a Belgian academic and adviser on language policy to the European Commission. But across much of the continent, firms do the bulk of their business with their neighbours. Dutch firms need delivery drivers who can speak German to customers, and vice versa. Belgium itself is a country divided between people who speak Dutch (Flemish) and French. A local plumber needs both to find the cheapest suppliers, or to land jobs in nearby France and the Netherlands.

“English, in effect, blocks the learning of other languages,” claims Mr Baetens Beardsmore. Just as the global rise of English makes life easy for idle Britons or Americans, it breeds complacency among those with English as their second language. “People say, ‘well, I speak English and I have no need to learn another language.'” He cites research by the European Commission suggesting that this risk can be avoided if school pupils are taught English as a third tongue after something else.

A huge government-financed survey of Brussels businesses reveals a dire shortage of candidates who can speak the right local languages (40% of firms have reported losing contracts because of a lack of languages). One result is a very odd labour market. By day, Brussels is more or less bilingual, hosting a third of a million Dutch- and French-speaking commuters from the prim suburbs, who fill the lion's share of well-paid graduate jobs. Once night falls, Dutch-speakers are in a small minority.

Not getting on their bikes

Moreover, among permanent Brussels residents, unemployment hovers around 20%. Just a short journey away, in Dutch-speaking suburbs such as Zaventem (home to the airport), unemployment is 4-5% and employers complain of worsening labour shortages. Even within Brussels, thousands of job vacancies go unfilled every month because nine in ten jobseekers cannot read and write in French and Dutch, prompting employers to bin their applications.

Olivier Willocx of the Brussels Chamber of Commerce and Industry argues that too many Brussels natives are “allergic to learning Dutch”. The rise of Dutch is painful for some. French was once the language of the Belgian and Brussels elite, but the post-war period has seen Dutch-speaking Flanders (as the north of Belgium is known) boom. “Like it or not, the real economic power in Brussels is Flemish,” contends Mr Willocx.

Hardline nationalist politicians in Flanders must take some blame because they have done a lot to make French-speakers feel unwelcome. The head of the Brussels employment service, Eddy Courthéoux, also questions the sheer number of job advertisements that demand both Dutch and French, saying that for some “it is just a way of avoiding hiring a foreigner”: code for Moroccan, Turkish or African immigrants.

Perhaps Brussels should accept its fate as an international city, and switch to English, like some European Singapore (although with waffles, frites and dirty streets)? For all his problems finding jobs for monolingual locals, Mr Courthéoux looks appalled. “Living in a bilingual city is not a misfortune, it makes life rich and interesting,” he argues. Some would call this pure sentiment, others might suggest that it reflects hard-nosed economics. But Brussels is actually a good place in which to hear the point and simply nod your head.

----------------

(b) Some governments actually do adopt a "major" language and force all residents to use it, even when most residents might not have known that language previously. In some cases different minorities voluntarily adopt a foreign language they will all use in common in business transactions or law courts.

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/31/world/asia/31timor.html?ref=world

New York Times, July 31, 2007

Dili Journal

A New Country’s Tough Non-Elective: Portuguese 101

By SETH MYDANS

DILI, East Timor — The rumble of a generator and the whir of ceiling fans muffled the quiet words of a judge as he questioned a witness in a murder trial here one recent hot, still afternoon.

But even if they could have heard him, most of the people sprinkled through the little courtroom, including the defendant and the witnesses, could not have understood what he was saying.

The judge was speaking in Portuguese, the newly designated language of the courts, the schools and the government — a language that most people in East Timor cannot speak.

The most widely spoken languages in this former Portuguese colony are Tetum, the dominant local language, and Indonesian, the language of East Timor’s giant neighbor.

For a quarter of a century, Portuguese had been a dying tongue, spoken only by an older generation. It was banned after Indonesia annexed the territory in 1975 and imposed its own language.

In a disorienting reverse, a new Constitution re-imposed Portuguese after East Timor became independent in 2002. The marginalized became mainstream again, and the mainstream was marginalized.

Linguistic convenience was sacrificed to politics and sentiment. In a nation that had never governed itself and had few cultural symbols to unite it, this language of resistance to the Indonesian occupiers was an emblem — particularly to the older generation — of freedom and national identity.

The choice has brought a tangle of complications, disenfranchising a generation of Indonesian speakers and introducing a new language barrier among the country’s many other problems.

Along with a struggle to provide health care, education, government services, jobs and even food for its people, East Timor is now on a crash course to learn its own official language, importing scores of teachers from Portugal to help.

“I have finished two levels of Portuguese, but I still don’t speak it well, just basic Portuguese,” said Zacharias da Costa, 36, a lecturer in conflict management at the National University of East Timor.

Within five years, according to the government’s plan, he will be required to teach all his courses in Portuguese, a language that is hardly heard on the campus here.

A bulletin board at the entrance to the campus carries 14 notices from teachers. Eight are written in Tetum, four in Indonesian and two in English. None are in Portuguese.

For all its awkwardness, East Timor’s experience is not uncommon, said Robert B. Kaplan, a senior co-editor of the journal Current Issues in Language Planning.

The imposition of new national languages happens when countries are colonized and it happens when they decolonize, he said. Sometimes, as in East Timor, it happens a second time when they decolonize again.

East Timor’s language problems are those of many countries that decree a language shift, complicating the daily business of the nation and cutting off its people from their history and literature, which has been written in what may well become an alien language.

In Azerbaijan, for example, a former Soviet republic that is now fully independent, a simple change in alphabet, from Cyrillic to Roman, has created a new class of illiterates.

East Timor’s courts are among the hardest-hit institutions. Translations back and forth among Portuguese, Tetum and Indonesian produce a game of telephone in which outside monitors say testimony is often distorted.

During a just-completed parliamentary election, news conferences were held in four languages, sometimes producing somewhat different versions of the news.

At The Timor Post, an English-language newspaper, reporters said they could not read government news releases in Portuguese, so they ignored them.

The reported number of Portuguese speakers in East Timor varies widely, perhaps because of different standards of fluency and perhaps because of the effects of the current language-training programs.

The United Nations reported in 2002 that only 5 percent of the population of 800,000 spoke Portuguese. In the 2004 census, 36 percent said they had “a capability in Portuguese,” said Kerry Taylor-Leech, a linguist at Griffith University in Australia who has written about the languages of East Timor. “Since the 1990s, you’ll see that a language shift has taken place,” she said. “The changes from what I see are taking place quite rapidly.”

According to the census, 85 percent claim a capability in Tetum, 58 percent in Indonesian and 21 percent in English.

The new Constitution establishes Portuguese and Tetum as the country’s two official languages, but Tetum is seen as thin and undeveloped, and most of the nation’s official business is conducted in Portuguese.

“This is a political decision and I have to implement it, like it or not,” said Judge Maria Pereira, a Dili District Court judge who has taken crash courses and now writes her decisions in what she calls fairly good Portuguese. “I have no choice. As a judge I have to implement the law.”

Some young Indonesian speakers, who had at first opposed the use of Portuguese, now say they embrace it as a means of enriching and developing Tetum. Already as much as 80 percent of Tetum is made up of Portuguese loan words or Portuguese-influenced words, Ms. Taylor-Leech said, although she said speaking Portuguese was unlikely to increase this number.

Another approach comes from President José Ramos-Jorta, one of the authors of the Portuguese-language law. “We have to rethink our language policies,” he said in a telephone interview.

As a first step, he said, English and Indonesian should be added to Portuguese and Tetum as official languages. “I see no problem with a nation having four official languages.”

But his plan does not end there, suggesting that questions of language could preoccupy his country for years to come.

Once they have become accustomed to their four official languages, he said, “We can give the people the option to choose two of them as compulsory languages.”