ORDER OF TOPICS:

INTRODUCTION -- THE FALSE CLAIM AND WHY IT IS IMPORTANT

QUOTES TO SHOW THAT THE FALSE CLAIM IS ACTUALLY ASSERTED

EVIDENCE TO SHOW THAT THE CLAIM IS FALSE

FULL TEXT OF THE ARTICLE ABOUT MAUNA ALA, INCLUDING SOME PHOTOS

ARTICLE FROM HONOLULU STAR-BULLETIN OF SUNDAY OCTOBER 30 2005 WHICH REPEATS THE CLAIM THAT MAUNA ALA REMAINS "ROYAL LAND UNDER THE HAWAIIAN FLAG" AND THAT WHEN ENTERING THE GATES OF MAUNA ALA "... THE WESTERN WORLD AND ITS LAWS AND CUSTOMS ARE LEFT BEHIND ON NUUANU AVENUE" (The main focus of this Star-Bulletin article is about the failure of the former head of Hui Malama to return a loan of two sacred kapu sticks borrowed under false pretenses several years previously).

ARTICLE FROM HONOLULU ADVERTISER OF FEBRUARY 22, 2006 REGARDING BILL IN STATE LEGISLATURE TO PROVIDE DEDICATED FUNDING FOR MAINTENANCE OF MAUNA ALA

TV NEWS REPORT FROM KITV OF OCTOBER 21, 2015 REPORTING THAT THE SON OF THE RECENTLY DECEASED CURATOR HAS NOW OFFICIALLY BECOME THE NEW CURATOR.

===============

INTRODUCTION -- THE FALSE CLAIM AND WHY IT IS IMPORTANT

The article that is the subject of this webpage was published in Midweek newspaper in two installments: Volume 20, No. 4 of May 19, 2004 and Volume 20, No. 5 of May 26, 2004. An additional, related article was published in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin of Sunday October 30, 2005, and is copied at the bottom of this webpage (The Star-Bulletin is published by the same company as Midweek).

The article is a fascinating summary of the history of Mauna Ala -- the Royal Mausoleum. It is also a story about the family that has been the constant caretaker of Mauna Ala, and of the bones of all the Kamehameha kings including Kamehameha the Great.

The clear purpose of the article is to evoke feelings of profound respect for Mauna Ala, for the caretaker family, and for the native Hawaiian tradition of caring for the bones of the ancestors. The article succeeds very well in evoking those feelings. This webpage should not be seen as any sort of attack on those feelings.

But in its effort to evoke feelings of respect and awe the article is also filled with mystery-mongering, including stories of ghosts and strange happenings. While the "obake stories" might add an element of sensationalism that stimulates public interest and encourages families to bring the kids along when they visit (especially around Halloween), the mystery-mongering does tend to detract from the article's seriousness and its credibility. The overall impression is that the article is an example of mo'olelo -- a storytelling by an author who begins with a political or moral viewpoint and then uses a blend of fact and fiction, selecting favorable things and leaving out unfavorable things in order to weave a story supporting that viewpoint.

One of the ways to get public support for Hawaiian sovereignty is to encourage people to believe that ethnic Hawaiians are an "indigenous" people -- a separate and distinct "native" or "aboriginal" people deserving collective special treatment, under the law, for their group. The general public expects that if a group is truly indigenous, then that group will have collective hidden knowledge, secret ceremonies, and special kinds of spirituality that make them inherently different from anyone else. That's why the mystery-mongering in this article is so important. It's part of a larger public-relations political campaign that deserves puncturing, without in any way attacking the core of respect for Mauna Ala, for the caretaker family, and for ancient Hawaiian burial customs.

One major focus of the Midweek article is an extreme example of mystery-mongering which makes a statement that is allegedly factual but turns out to be totally false. It is a claim that Mauna Ala was carved out as an exception to the ceding of Hawai'i's public lands to the United States at the time of the Annexation -- a claim that Mauna Ala remains today a piece of the Kingdom of Hawai'i where the laws of the United States and the State of Hawai'i do not apply. Everyone understands that ghost stories and strange happenings are fun to talk about and need not be taken too seriously. But a statement claiming as fact that a piece of the Hawaiian Kingdom still remains free from the sovereignty of the United States is a very serious matter. Actually, it is a weird kind of ghost story -- that a political ghost of the Kingdom of Hawai'i still haunts Nu'uanu Valley on a 3.5-acre piece of land where Kingdom sovereignty was never lost.

After each of the two installments of the Midweek article, Ken Conklin submitted the following letter to editor of Midweek. This letter was never published. It's easy to see why!

----------------

Mauna Ala NOT separate or sovereign

Mahalo to Don Chapman for his 2-part series on the fascinating history of Mauna Ala and some of the spooky myths associated with it.

One of those myths is the claim that Mauna Ala was somehow "removed from the public domain" in the Organic Act; and "federal land laws ... and now state laws" do not apply there; and it retains "separateness and sovereign status."

I have re-read the Organic Act of 1900 and cannot find any exemption for Mauna Ala. I have also checked the Honolulu list of property ownership, which says Mauna Ala is owned by the State of Hawai'i in fee simple. Indeed, there have been several building permits over the years, issued to State of Hawaii Division of Parks, as owner. The Hawaiian flag flies alone there (and at 'Iolani Palace) as an act of aloha, not by sovereign right.

===============

QUOTES TO SHOW THAT THE FALSE CLAIM IS ACTUALLY ASSERTED

Midweek is a once-per-week newspaper published only on the island of O'ahu, owned and printed by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin publishing company. It usually contains one or two major articles about local personalities, plus several regular weekly articles by local columnists or by nationally syndicated columnists. The newspaper is distributed free of charge by U.S. mail to everyone on O'ahu who cares to subscribe; officially dated on Wednesday but often appearing in mailboxes on Monday or Tuesday. Midweek is the primary vehicle for distributing advertising circulars for supermarkets and other local businesses; and also contains an extensive list of local events.

The cover of Midweek for May 19, 2004 has a large photo of the man who is the focus of the article. His photo is surrounded by a picture frame with two royal crowns over the top of it. At the bottom is the title: "Still Serving Hawaiian Royalty" and the further front-page caption: "Willaim Kaihe'ekai Mai'oho, descended from two brothers chosen by Kamehameha the Great to hide his bones, continues a family tradition as curator of the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna Ala"

The cover story begins on page 3, with the title "A Family Tradition Born in Mystery". A bold-face subtitle says: "Thanks to Queen Lili'uokalani, the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna Ala is the last remnant of the Kingdom of Hawaii, where federal land laws do not apply".

Later in part 1, from May 19, the following statements can be found. Everything in the remainder of this section of this webpage is a continuous segment of the article, most of which is quoting the words of the caretaker talking to the newspaper reporter (hence the double quote marks):

------------

"OUR story is also about the only place in Hawaii where neither state nor federal land laws apply. These peaceful 3.5 acres are the last surviving remnant of the Kingdom of Hawaii."

""Yes, this is it," Kaihe'ekai says.

""And who made it safe in that respect was Queen Lili'uokalani and George Wilcox. Although they were political rivals and really didn't like each other, they worked together — he had the in as Hawaii's first delegate to Congress.

""In May 1900 (seven years after the overthrow of the native monarchy) when the Organic Act was passed by the Congress of the United States, creating the Territory of Hawaii, Lili'uokalani and Wilcox worked to have Mauna Ala removed from the public domain. Which means that federal land laws do not apply to the grounds of Mauna Ala, nor now state laws. Mauna Ala is the only place that flies the Hawaiian flag by itself, honoring our ancestral chiefs. By American law, whenever a public facility opens, the American flag is highest, the state flag second. Here at Mauna Ala is proudly displayed only the flag of the nation of Hawaii, created by Kamehameha. So it's even more intense, even more of a symbol of Mauna Ala's separateness and sovereign status. I tell people, when you come to Mauna Ala, you enter a different world.

""It's magnificent and overwhelming, this thing, for lack of a better word, they created to care for us, the Hawaiian people. So Mauna Ala in this sense, this separateness again, it is a place of refuge. It is where our iwi, the most important part of our being, links us through the generations, to remember them and their aloha to us.

""The example I use for children (on school outings), when they built Pali Highway it would have been cheaper to come straight down Nuuanu Avenue, but because of Mauna Ala they couldn't. Oahu and Nuuanu cemeteries could have been moved — they've done it at Kawaihao Church to widen Queen Street, exhumed and moved iwi, for the public good it's called in the law. But because of Mauna Ala's removal from the public domain, they had to go and blow up Pacific Heights and make Pali Highway go down into Bishop Street.

""Mauna Ala is immovable, and Queen Lili'uokalani did that for her ancestors, and for the Kamehamehas, to keep them secure and sacred, to have this inserted into the Organic Act. So only the flag of Kamehameha and the nation of Hawaii flies here."

"Queen Lili'uokalani, perhaps, is winking somewhere. Her kingdom was stolen, but she preserved a bit of it for all time at Mauna Ala by using the laws of the nation that helped steal her throne."

===================

EVIDENCE TO SHOW THAT THE CLAIM IS FALSE

The false claim in the article was that Mauna Ala was protected in the Organic Act of 1900, so that it was never transferred to the United States as part of the ceded lands, and was (therefore also) never ceded back to the new State of Hawai'i as part of the ceded lands at Statehood in 1959.

It's nearly impossible to prove that something DID NOT happen. However, two strong pieces of evidence can be provided. First of all, the complete text of the Organic Act can be checked to verify that Mauna Ala is never mentioned as an exception. Second, real estate ownership records can be checked to see who is the current fee-simple owner of Mauna Ala.

The Organic Act was passed by Congress on April 30, 1900 as C 339, 31 Stat 141. Full text is available on the website of the "Nation of Hawai'i" at:

http://www.hawaii-nation.org/organic.html

A search of the document's text shows no mention of "Mauna Ala" or "Royal Mausoleum." Anyone who has a word processing program can copy and paste the entire document and do a computerized "find" search of the text, using whatever key word(s) might seem appropriate. Nothing will be found.

Additional evidence comes from a joint resolution passed by Congress on May 31, 1900 as Public Resolution No. 28. The text of that resolution reads:

"Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress Assembled, That the following described lands lying and being situate in the city of Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands, heretofore used as a mausoleum for the royal family of Hawaii, to wit: the mausoleum premises, beginning at ... [detailed description of meets and bounds] ... be withdrawn from sale, lease, or other disposition under the public-land laws of the United States."

A photograph of the complete resolution, from the Archives of the State of Hawaii, is on this website at:

https://www.angelfire.com/hi5/bigfiles3/Maunaala1900CongReso.pdf

The following points from the Congressional joint resolution regarding Mauna Ala provide further evidence that Mauna Ala was never exempted from the Organic Act or in any way preserved as sovereign territory of the Kingdom of Hawai'i following annexation: (1) That Mauna Ala resolution was a joint resolution of Congress, exercising control over Mauna Ala -- the U.S. Congress clearly had control of Mauna Ala at the time the resolution passed on May 31, 1900. (2) Presumably Congress had that jurisdiction because Mauna Ala was part of the ceded lands. Note that the lands were ceded at the time of Annexation in August 1898, and that full implementation of annexation including all land issues were resolved in the Organic Act passed by the U.S. Congress on April 30, 1900; whereas the Mauna Ala resolution was passed on May 31, 1900. (3) The closing sentence of the resolution regulates disposition of Mauna Ala "... under the public land laws of the United States", not under the public land laws of the Kingdom of Hawai'i.

The City and County of Honolulu maintains careful records of all the real property on the island of O'ahu, including its assessed valuation and building permits. That information is now available at a government website. By inputting a street address, it is possible to discover the owner's name, assessed valuation, and perhaps to get information about building permits. A map is also provided to show the location of the property in its neighborhood, and its approximate boundaries.

The address of Mauna Ala is 2261 Nuuanu Ave., as printed at the end of the newspaper article. Also, the correctness of that address is confirmed by the records contained on the website for that address containing the name Royal Mausoleum in one of the building permits.

The URL where the address can be input, and a map will be shown, is:

http://gis.hicentral.com/website/parcelzoning/viewer.htm

The resulting page called "property information" for this address says:

Property Information

22021012:0000

2261 NUUANU AVE

Building Value: 75,700

Building Exempt: 75,700

Land Value: 2,615,800

Land Exempt: 2,615,800

Land Classification: Unimproved Residential

Clicking on "owner information" produces this page clearly identifying the owner of this property as "State of Hawai'i" as owner in fee simple.

Owner Information

22021012:0000

2261 NUUANU AVE

Name: STATE OF HAWAII

Type: Fee Owner

Clicking on "building permits" takes us to a different website, for dpp (Department of Planning and Permitting), where this particular address has its list of building permits. The building permits identify that this is the Royal Mausoleum, and that the building permits were issued to the owner State of Hawai'i, DLNR (Department of Land and Natural Resources), Division of State Parks (incidentally, 'Iolani Palace also has the same owner). Unfortunately the columns in the document cannot be maintained on this webpage, so the information appears scrambled; but it clearly confirms what was just stated; and the reader may go directly to the dpp government website and read it for himself.

http://dppweb.co.honolulu.hi.us/DPPWeb/default.asp?PossePresentationId=300&PosseShowCriteriaPane=No&TMK=22021012

Application Number Building Permit No. Issue Date TMK Status Description View Details 088935-V(HIST) Sep 9, 1977 22021012- Converted ROYAL MOSELEUM - ,EL View Details 188142 Dec 28, 1983 22021012- Completed EL View Details A1983-12-1116 086952 Jul 29, 1977 22021012- Completed HOONANI MAUNAALA - RP,EL View Details A1984-03-0586 191199 Mar 21, 1984 22021012- Completed ROYAL MAUSOLEUM - RP,FC View Details A2000-05-0651 mmm dd, yyyy 22021012 Permit approved to issue [TMK: 22021012] State of Hawaii/DLNR Div of State Parks - new curators residence at the Royal Mausoleum State Monument View Details A2000-05-0656 mmm dd, yyyy 22021012 Permit approved to issue [TMK: 22021012] State of Hawaii/DLNR Div of State Parks - demo curators residence at the Royal Mausoleum State Monument

==================

FULL TEXT OF THE ARTICLE ABOUT MAUNA ALA, INCLUDING SOME PHOTOS (unfortunately Midweek does not maintain archives. This valuable material is otherwise unavailable, and the context for the quotations would be lost)

Midweek is a once-per-week newspaper published only on the island of O'ahu, owned and printed by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin publishing company. It usually contains one or two major articles about local personalities, plus several regular weekly articles by local columnists or by nationally syndicated columnists. The newspaper is distributed free of charge by U.S. mail to everyone on O'ahu who cares to subscribe; officially dated on Wednesday but often appearing in mailboxes on Monday or Tuesday. Midweek is the primary vehicle for distributing advertising circulars for supermarkets and other local businesses; and also contains an extensive list of local events.

The cover of Midweek for May 19, 2004 has a large photo of the man who is the focus of the article. His photo is surrounded by a picture frame with two royal crowns over the top of it. At the bottom is the title: "Still Serving Hawaiian Royalty" and the further front-page caption: "Willaim Kaihe'ekai Mai'oho, descended from two brothers chosen by Kamehameha the Great to hide his bones, continues a family tradition as curator of the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna Ala"

The cover story begins on page 3, with the title "A Family Tradition Born in Mystery". A bold-face subtitle says: "Thanks to Queen Lili'uokalani, the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna Ala is the last remnant of the Kingdom of Hawaii, where federal land laws do not apply".

Bill Mai'oho

By Don Chapman

This is the first in a two-part series [May 19, 2004]

With all that has changed in Hawaii during the 185 years since Kamehameha the Great ruled these islands, one thing remains the same. The family of William Kaihe'ekai Mai'oho still serves the kings and queens of Hawaii by tending to their iwi, their bones.

Mai'oho is the kahu/curator of the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna Ala in Nuuanu Valley, where rest the iwi of every royal since Kamehameha but one. It's a job previously held by his mother, grandmother and grandfather, also named Kaihe'ekai, and two of his grandfather's forebears. His son, another Kaihe'ekai, will one day succeed him.

More than just a family name, Kaihe'ekai offers the only known clue to one of the great mysteries in Hawaiian history — where lie hidden the remains of Kamehameha?

The resting place of the great king's iwi is a question no less relevant today than it was when he died in 1819, as evidenced by the ongoing feud over the bones of long-dead ali'i, royalty, on the Big Island — should they be left sealed in their original burial cave near Kawaihae, which had previously been raided, or moved to the Bishop Museum? More than 30 groups have declared an interest in the debate, including descendants of those chiefs, who fear descendants of rival chiefs of yore might desecrate the iwi.

This is not an unreasonable concern because, as we shall see, ancient Hawaiians made an art form of desecration.

THERE are few areas where modern Western sensibilities bump up harder against traditional Hawaiian beliefs and values than on the issue of human remains. While bones in the English language are plural, a rather impersonal collection of calcium deposits that tend to lose density as a person ages and to show up at Halloween on cartoonish costumes, in Hawaiian iwi is singular, defining one connected entity, the repository of mana, spiritual energy, what might in other cultures be called karma or soul.

So in recent years, Hawaiian iwi have rerouted highways, moved the sites of hotels and delayed or stopped construction of other projects.

"The iwi are incorruptible," Kaihe'ekai says. (In attributing quotes to the man friends call Bill, we're using Kaihe'ekai, for he's speaking not just on his own behalf but also for the ancestors who have carried on a tradition and a responsibility since 1819 and for those he hopes "will be speaking of these things a thousand years from now, whatever that world looks like.")

"It is so much like the Christian way of looking at it," he says. "The flesh is weak, but the iwi remain in its wholeness and sacredness. There is mana attached to the iwi of our ancestors. I believe that these iwi continue to sustain us as a people."

The Hawaiian dictionary co-authored by Mary Kawena Pukui, the great Hawaiian scholar (and ohana, family, from Ka'u of Kaihe'ekai's grandmother Emily Kekahaloa Namauu Taylor), defines iwi simply as bone, and then explains "bones of the dead, considered the most cherished possession, were hidden."

"From what Mary Kawena has written," Kaihe'ekai says, "and what my mom and grandpa said, the iwi is the essence of a person. That's why we revere and honor sites such as this at Mauna Ala, and other heiau in Hawaii, because it holds that total mana and essence of our ali'i, contained in the iwi.

"All our lifelong works, the iwi become saturated with that, and it tends to hold on to that. Not only the physical … the spiritual entity remains. The iwi is encased in the mana of the person … But because of the ancestors, we incorporate what they did in their lifetime … In that way, the totality of the person remains in the genetics of your ancestral line."

In that, Hawaiians were intuitively centuries ahead of modern science, which only in recent years is finding ways to discern DNA, the genetics of our ancestral lines, in human bones.

HIS photo is on the cover, but this story is not about Bill Kaihe'ekai Mai'oho. "I wish you could have done a story on my mom," he says. "She was better at this kind of thing. Or my grandpa."

A shy and humble man, he agreed to be interviewed by MidWeek largely because his friend, musician Palani Vaughnn, suggested the story to us after being featured in a recent Old Friends column. He agreed, he says, not for himself, but for his family, for the royals he still serves, to dispel false notions about the Royal Mausoleum — such as the one that Mauna Ala is closed to the public (not since 1947) — and to remind native Hawaiians and all others of the peace and power of this remarkable place.

So our story is about the Kaihe'ekai connection. It's about the ali'i his family cherish and serve. It's about Mauna Ala, a place alive with the mana of largely altruistic men and women who loved, led and served the people of Hawaii. It's about a quiet place nestled between the rush and bustle of Pali Highway and Nuuanu Avenue, where if you listen, you can hear the whispers of kings, queens, high chiefs and chiefesses, and feel them walking beside you, just as they once walked among their people.

As Kaihe'ekai, a bachelor, says: "I'm never alone here."

OUR story is also about the only place in Hawaii where neither state nor federal land laws apply. These peaceful 3.5 acres are the last surviving remnant of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

"Yes, this is it," Kaihe'ekai says.

"And who made it safe in that respect was Queen Lili'uokalani and George Wilcox. Although they were political rivals and really didn't like each other, they worked together — he had the in as Hawaii's first delegate to Congress.

"In May 1900 (seven years after the overthrow of the native monarchy) when the Organic Act was passed by the Congress of the United States, creating the Territory of Hawaii, Lili'uokalani and Wilcox worked to have Mauna Ala removed from the public domain. Which means that federal land laws do not apply to the grounds of Mauna Ala, nor now state laws. Mauna Ala is the only place that flies the Hawaiian flag by itself, honoring our ancestral chiefs. By American law, whenever a public facility opens, the American flag is highest, the state flag second. Here at Mauna Ala is proudly displayed only the flag of the nation of Hawaii, created by Kamehameha. So it's even more intense, even more of a symbol of Mauna Ala's separateness and sovereign status. I tell people, when you come to Mauna Ala, you enter a different world.

"It's magnificent and overwhelming, this thing, for lack of a better word, they created to care for us, the Hawaiian people. So Mauna Ala in this sense, this separateness again, it is a place of refuge. It is where our iwi, the most important part of our being, links us through the generations, to remember them and their aloha to us.

"The example I use for children (on school outings), when they built Pali Highway it would have been cheaper to come straight down Nuuanu Avenue, but because of Mauna Ala they couldn't. Oahu and Nuuanu cemeteries could have been moved — they've done it at Kawaihao Church to widen Queen Street, exhumed and moved iwi, for the public good it's called in the law. But because of Mauna Ala's removal from the public domain, they had to go and blow up Pacific Heights and make Pali Highway go down into Bishop Street.

"Mauna Ala is immovable, and Queen Lili'uokalani did that for her ancestors, and for the Kamehamehas, to keep them secure and sacred, to have this inserted into the Organic Act. So only the flag of Kamehameha and the nation of Hawaii flies here."

Queen Lili'uokalani, perhaps, is winking somewhere. Her kingdom was stolen, but she preserved a bit of it for all time at Mauna Ala by using the laws of the nation that helped steal her throne.

And how different would life be in 21st century Honolulu if Nuuanu Avenue and not Bishop Street were the downtown receptacle of highways from the Windward and Leeward sides of Oahu?

THE name Kaihe'ekai dates to 1819, when Kamehameha the Great understood the end of his reign and his life were at hand. There were plans to be made, for the infant nation, for the afterlife of a king in his 67th year. As Kaihe'ekai tells his family story, the names of ancient kings and queens and long-ago dates roll off his tongue as easily and matter-of-factly as you talking about your sister's wedding or your cousin's graduation. The oral tradition of old Hawaii is alive and well at Mauna Ala.

"My tenure here at Mauna Ala is through family genealogy," says Kaihe'ekai, 58, who has been at Mauna Ala since age 2, kahu since 1995.

"Two high chiefs, Hoapili and Ho'olulu, were chosen by Kamehameha to hide his iwi after his passing. Hoapili and Ho'olulu were the sons of Kame'eiamoku. On the coat of arms of the nation (and today the state) of Hawaii are the royal kapu twins, Kame'eiamoku and Kamanawa, uncles of Kamehameha the First. They were a generation older than Kamehameha. Kamehameha had terrific insights into psychology, and Hoapili and Ho'olulu were the next generation of chiefs who were trusted by Kamehameha. These two high chiefs became his very, very trusted chiefs, especially Hoapili."

Hoapili was born Ulumaiheihei, but Kamehameha gave him the name Hoapili, "attached to the bosom," a sign of his trust and aloha. So it was that Hoapili, the older brother, and Ho'olulu were chosen to hide the iwi of Kamehameha.

"Ho'olulu went to Ahu'ena Heiau in Kailua-Kona and retrieved the iwi of Kamehameha, and met Hoapili in a canoe," Kaihe'ekai continues. "In our family history it talks about these two chiefs, along with Keopulani, Kamehameha's most sacred wife, and they went into an undersea cavern to hide the iwi of Kamehameha, which until today still has never been found. (A kapu, taboo, remains on the site in perpetuity.)

"Ho'olulu comes back from this responsibility to the king, and about a month later he has a son born to him, and he names him Kaihe'ekai, after the event. (Siblings would also receive names commemorating the hiding of the king's iwi.) In the literal translation, Kaihe'ekai means ocean-octopus-ocean. But in the kauna, or hidden meaning, it means the receding waters, like the octopus recedes and hides in the puka. They went into this undersea cave, came up in a cavern, and hid the iwi of Kamehameha.

"So our family has been connected with the caring of the Kamehameha family, and now the Kalakaua family, since the passing of Kamehameha in May 1819."

And the secret of the cave's location?

"It went with those three individuals, Keopulani, Hoapili and Ho'olulu."

Today, the modest residence on the grounds of Mauna Ala where Kaihe'ekai lives is called Hale O Ho'olulu.

THE dying king had good reason to fear the desecration of his iwi. Kamehameha had done a little desecrating in his time.

"There were good chiefs and bad chiefs, and the bad ones, whole groups of people rebelled against them," Kaihe'ekai says, explaining the finer points of the art. "They didn't need the leadership of the ali'i to make war. If the chief was bad, he was done away with and his iwi were made into fish hooks. Or arrow points, and then used to shoot rats — they had bows and arrows, didn't use them in warfare, but they'd shoots rats. And they'd turn around and tell the family, oh, look what your grandpa went catch for me — desecrating them. Or using the fishing hook made of bone… in Hawaiian stories, the canoes coming in with a big fish, the other family going out, they say, 'oh, you're not going catch the big fish — look, your grandpa already caught this for us, so you can just go back home.'

"Kamehameha, when he was conquering Oahu, the high chief Kalanikupule ran away into the mountains, but was caught a few weeks later and sacrificed in Moanalua Valley. And Kamehameha takes his thigh bone and uses it as a kahili (a feather-topped symbol of royalty). That kahili went into the collection of Queen Emma and is now at the Bishop Museum.

"So the iwi had great significance, both good and bad, and when you dispel your opponent, when you take away their life, you also want to take away the family connection, desecrate the family so no one will rise up from that family to overtake or displace you as a high chief."

MAUNA ALA translates literally as fragrant mountain. "But when you look at the kauna," Kaihe'ekai says, "mau is to perpetuate, na is the, ala is path. And so you perpetuate the path of our ancestors, and we speak about them in the most sacred way. I am here with them, and I speak of them and their families in the most reverent way."

Before it became the final resting place of every Hawaiian royal since Kamahemahea's iwi were hidden in that Big Island sea cavern except one (King Lunalilo, interred at Kawaihao Church), Mauna Ala was the property of Kamehameha III (Kauikeaouli) and Kamehameha IV (Alexander Liholiho) and Queen Emma.

"They had lo'i, taro patches, private ones for the king and his family," Kaihe'ekai says. "There were little puuwai (small streams) along Nuuanu Avenue in ancient times. Laura Judd lived across the street and writes in her journal of seeing the king and queen and their retainers come here and create the lo'i patches, and the king's horses inside packing down the dirt. And a lot of these old pohaku (lava rocks) are pohaku Kamehameha the Fourth himself placed here, creating the lo'i."

Now so tranquil and quiet, a lovely place for prayer or meditation, Mauna Ala was once the scene of high-decibel warfare.

When up to 30,000 warriors of Kamehameha attacked in his ultimately successful bid to unite the Hawaiian islands for the first time under one chief, Mauna Ala was the first battle encampment of the Oahu chief Kalanikupule.

"This is the first prominent spot in the valley," Kaihe'ekai says. "Up on the hill beside the Kamehameha crypt, there are ship chains wedged into the rock — Kalanikupule had his cannons strapped down here at Mauna Ala to repel Kamehameha. Oahu warriors, Maui warriors, Hawaii warriors, Kauai warriors, their blood was shed here, and that lends itself to Mauna Ala's mana and power.

"The largest encampment, of course, was at (what later became) Queen Emma's Summer Palace (a short distance up the valley). The road in the back is called Puiwa, which means to frighten. The valley kind of narrows at that point. And Kamehameha's largest cannon, which he called Lopaka, made by John Young (one of six white men interred at Mauna Ala) and Isaac Davis, reverberated through the whole valley, it frightened the Oahu warriors, and they fled (up the valley, many leaping to their death from the cliffs of the Pali)."

Petroglyph carvings along the ancient trail that parallels Nuuanu Stream, so close Kapena Falls can be heard at night from Mauna Ala, also add to the historic specialness of this place. Carvings in stone depict warriors with a rainbow curving protectively over their heads, the original Rainbow Warriors. Then there's the legend of Kaupe, ghost dog of Nuuanu, that would bark to warn people of the fearsome coming of night marchers.

All of it "lends itself to the sacredness of Mauna Ala," Kaihe'ekai says. "I truly believe that Mauna Ala was chosen for the site of the Royal Mausoleum by King Kamehameha the Fourth and Queen Emma because of that."

HOLD on a second. Did Kaihe'ekai really say "I'm never alone here"?

Yes, he did, and next week we'll get into the subject of ghosts and spirits, as well as how Kaihe'ekai was "protected" by a debilitating illness that kept him bed-ridden from age 14 to 21, and a poetic conclusion to one of the greatest love stories ever told.

-------------

This is the second in the two-part series. [May 26, 2004]

A Family Tradition Born in Mystery

By DON CHAPMAN

IT DOESN'T always happen this way, but the cameras worked just fine when a scene for a John Wayne western was filmed at Mauna Ala, the Royal Mausoleum, where rest the iwi, bones, of every Hawaiian royal since Kamehameha the Great but one.

Maybe the Duke got lucky, or maybe his crew just had to learn a lesson, as happened on the more recent day an Olelo TV crew came to Mauna Ala in Nuuanu Valley. When it was time for lights, camera, action, and they started shooting, the viewfinder stayed blank, the tape rolled but recorded nothing.

"We forgot to ask permission," says Dr. Peggy Oshiro, acupuncturist.

They stopped, in a lingering moment of silence asked the spirits of high chiefs and chiefesses who reside at Mauna Ala for their blessing.

"When we turned the camera on again," Oshiro says, "everything was clear and in focus and the tape recorded just fine."

Other kinds of unusual things can happen to cameras at Mauna Ala. Things like people the photographer didn't see showing up in photos.

William Kaihe'ekai Mai'oho, kahu/curator of the Royal Mausoleum, pulls two photographs from his desk. The first, taken from near the Kamehameha crypt, looks out toward the gilded gate and the kamani tree that curls low like a protective centurion. In the branches of the tree appears to be a male face. It is wearing glasses. It looks a lot like the man wearing glasses in the photo behind the desk, his grandfather William Kaihe'ekai Taylor, kahu here from 1947, the year Mauna Ala opened to the public, until '56.

The second photo was taken from the gate looking in at the chapel. Near the top, in a circular stained-glass window designed by Queen Lilu'okalani, appears to be the silhouette of a man. A haole man. It looks a lot like Charles Bishop, who built the Kamehameha crypt.

That Hollywood film, by the way, was Big Jim McClean. In the brief scene shot at Mauna Ala, John Wayne is seen walking toward the chapel for James Arness' funeral.

GHOSTS? Spirits? Funny kine things with cameras? What's going on here?

"Whenever I have a group visiting, especially when it's keiki, they ask about ghosts," Kaihe'ekai says. "That's the first thing, 'Do you see ghosts?'"

(For readers who missed last week's introduction, in attributing quotes to the man friends call Bill, we're using Kaihe'ekai, for he's speaking not just on his own behalf, but also for the ancestors who have carried on a tradition and a responsibility since 1819, when Kamehameha the Great asked two brothers of high chiefly status, his cousins, to hide his bones after his death. Shortly after fulfilling that obligation, a son was born to one of those brothers, Ho'olulu, and he named the boy Kaihe'ekai, which hints at the secret location. Ever since, the family has served the kings and queens of Hawaii by tending to their iwi, following the Kamehamehas as the capital moved from Kailua-Kona to Lahaina to Honolulu. He's been kahu at Mauna Ala since 1995, a job previously held by his mother, grandmother and grandfather, and two of his grandfather's forebears.)

There is a g-word involved, but it's not spooky. Not ghosts, gifts.

"I call them gifts of power, things that are given to me by them, that I keep for myself," Kaihe'ekai says. "I won't speak about it, it's my treasure, it helps me to do what I do at Mauna Ala.

"When the keiki used to ask my mom, 'Oh, Auntie, you not scared to live ovah heah?' she'd say, 'I'm not scared of the ones who have passed, it's the live ones who frighten me.'"

Introducing the people of Hawaii, and those from other shores, to the historic deeds and graceful spirits of native royalty is one of the reasons he agreed to be interviewed by MidWeek.

"To let them come feel the presence of our ancestors, to be among them — not to be ho'okano, shy or embarrassed, or think ghosts, scared, no," he says.

"Because the spirits who are here … I believe Kamehameha, where else would he go in the islands? Spiritually, he would travel throughout all the islands, but his family is here, his sons are here, his favorite wife, where else would he come to visit and be? I believe that they are here 24/7. They go and they come, or they present themselves and they hide themselves again. But it is because the chiefs are so powerful (in the mana, spiritual energy, infusing their iwi) that they still have that awareness. And in that awareness, it links to the living.

"My mom called this the piko, the center, the source, where you can come and get inspiration by meditating, praying, looking at the example of their lives and what they did for the Hawaiian people."

The presence of royal spirits, he says, "it's an ever-present feeling, but it's beyond a feeling … So when people come seeking knowledge about our ancestors and the culture, when they leave they can go out and talk to people, perpetuate the way of life of our ancestors — the word has gone out. And they'll remember how they felt, just chickenskin throughout their time here at Mauna Ala.

"So it is a powerful thing to be among them and to help give the knowledge of our culture."

In researching this story, the author made five visits to Mauna Ala, plus a couple of slow drive-bys, and there's definitely something going on. Something chickenskin and more. And in a very positive way, if you come respectfully and quietly. It's because, Kaihe'ekai says, these Hawaiian royals were largely altruistic, and their spirits remain so.

"In life they set the policy for the culture," he says. "In that sharing, in that always giving, in that always supporting the people, they knew they would get support from the people they supported. It was a give and take that was almost equal … There was a stewardship, and it continued from the ancient time down to the modern era."

Ghosts, spirits, whatever … "I'm never alone here," Kaihe'ekai says.

SPIRITS must have been out and about on the night of Oct. 30, 1865, when King Kamehameha V (Lot Kapuaiwa) in formal procession brought 18 members of the Kamehameha family to Mauna Ala from the original royal mausoleum on the grounds of Iolani Palace.

"The king is on foot and leads the procession, using all the rituals of the Kamehameha family," Kaihe'ekai says, "their feathered kahili, their puloulou, symbols of the high chiefs. And they lay wreaths and pili grass all along King Street and Nuuanu Avenue and onto the grounds of Mauna Ala."

Thus, the first public arrival of chiefly iwi at Mauna Ala. Others, on other nights, had secretly preceded them. More on that momentarily.

That first royal mausoleum was built in 1825 on the diamondhead-makai side of the palace grounds to hold the iwi of Kamehameha II (Liholiho) and his Queen Kamamalu, who in London contracted the measles and died in July 1824.

"England's King George IV had them placed in beautiful mahogany caskets with silver shields in which were etched names and birth and death dates," Kaihe'ekai recounts. "He chose Lord Byron, cousin of the poet, to escort the king and queen home on HMS Blonde."

Until Kamehameha I, the iwi of all royals were secreted, sometimes in caves on sheer lava cliffs. The kauna, hidden meaning, of Kaihe'ekai hints that Kamehameha's iwi were placed in an undersea cavern — probably in ka'ai, sennet cordage woven around the bones, "so you can make out the upper torso of the human form," Kaihe'ekai says. Mother of pearl was often inlaid for the eyes.

Seeing the British caskets changed the way Hawaiian royalty would choose to be buried. So was built the first mausoleum, a small cottage-like structure of coral blocks and adobe. You can see where it was — a plaque and a small mound surrounded by a hedge of ti and a small fence.

That structure was already full by the time Prince Albert, son of King Kamehameha IV (Alexander Liholiho) and Queen Emma, died at the age of 4 in August 1862.

"Mauna Ala was conceived in the hearts of King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma after the passing of their son, Ka Haku O Hawaii," Kaihe'ekai says. "So they chose to turn the royal lo'i (taro ponds) at Mauna Ala into the Royal Mausoleum."

They hired Theodore Heuk, a German, to build it in the shape of the Roman/Greek cross, each side equal in length, in Gothic style. Today it is a koa-lined chapel used for celebrations on the birthdays of the royals of Mauna Ala.

As that building, too, began to fill, three crypts were built.

"Charles Bishop had the Kamehameha crypt built after Princess Pauahi died in 1884," Kaihe'ekai says. "With the passing of Queen Emma in 1885, there were no more Kamehamehas directly linked to the throne of Hawaii. On Nov. 9, 1887, the iwi of all Kamehamehas except the first were moved in another nighttime ceremony.

"After Charles Bishop's death in San Francisco in 1915 (he'd left Hawaii shortly after the overthrow of the native monarchy in 1893), his ashes were returned to Hawaii. Prince Kuhio carried his urn into the crypt, placed it on the casket of his wife, Princess Pauahi, and the vault was forever sealed."

Theirs is one of the greatest love stories ever told — the childless inter-racial couple who established a trust for the education of Hawaiian children, who created the Bishop Museum to bring preservation and serious scientific study to a Hawaiian culture and history they saw being overwhelmed by foreign influences — and there is something wonderfully poetic in this conclusion to their noble romance.

Royal palms roughly trace the parameters of the Kamehameha crypt, but because many of Charles Bishop's papers were lost in the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906, it is a mystery where each inhabitant is located. Consider it, Kaihe'ekai says, the final Kamehameha kapu, taboo.

A TIDBIT related to nothing else, and to everything: When infestations of white flies began to whitewash entire neighborhoods on Oahu in the 1980s, it was discovered that their only known natural predator is the black ladybug. Turned out Mauna Ala was black ladybug central, one of the rare places they flourished. Boy Scouts from Kamehameha Schools collected the little bugs and gave them to neighborhoods hardest hit.

AMONG other good deeds performed by Princess Pauahi and Charles Bishop was to hanai, unofficially adopt, the orphaned and abandoned William Kaihe'ekai Taylor.

"My grandpa was born in 1882, and when his mom died when he was 5 he was hanai'd to the Bishops," Kaihe'ekai says. "They had wanted to adopt, but my great-grandmother didn't want that. There were symbolic kapus attached to Princess Pauahi (children she'd formally adopted sadly died young), but they became my grandfather's godparents and stood at his baptism. So when my great-grandma passes away at the age of 28, her husband moves to California and leaves the kids. Four girls live at St. Andrew's Priory, Grandpa was raised with the help of Mr. Bishop."

When Charles Bishop fulfilled his late wife's wish to establish the Kamehameha Schools, "Mr. Bishop walked him onto campus and he became the first student admitted at Kamehameha, in October 1887 … Later, Mr. Bishop helps my grandfather get his position with the Dillingham family. He was a railroad engineer with the OR&L, and served the Dillinghams his whole life … When he got throat cancer, Walter Dillingham paid for the medical bills."

William Kaihe'ekai Taylor, who for reasons unknown would graduate from Iolani, was a member of the early Kamehameha Lodge. Because he was descended from the non-ruling side of King Lunalilo's family, he was a trustee of the Lunalilo Estate. At Lunalilo Home, the Dillinghams named the elevator for him, where his picture still hangs. And though he could have been interred at Mauna Ala, his iwi rest at Kawaiahao Church with Lunalilo, the people's king.

"He had this essence about him," Kaihe'ekai says of his namesake. "He had this relationship with people — an amazing man. I adored him."

When he passed in 1956, his wife Emily Kekahaloa Namau'u Taylor of Ka'u lineage succeeded him. She was a genealogist, fluent in Hawaiian, and wrote several songs, including Kuu Lei Awapuhi, written for the Jeff Chandler film Bird of Paradise and later recorded by Hapa.

"My grandparents put a lot of themselves into me. They had this aloha and I was the receiver. This treasure that is our tradition … they really imbued me with it."

His grandmother stayed as kahu until 1961, retiring to Lunalilo Home.

At this point the family line at Mauna Ala is briefly broken. Iolani Luahine, the legendary kumu hula, she of the illuminated eyes who would fall into a trance while dancing, served at Mauna Ala until 1965, then moved to become kahu at Hulihe'e Palace in Hilo.

FATE, or something like it, brought the family of Kaihe'ekai back to Mauna Ala.

"We didn't take the newspaper," he says, "so one of my mom's friends calls her, there's an article about the position opening up."

Chief, so to speak, among qualifications was genealogy.

"They required a letter, and three people interviewed the finalists — Liliu'okalani Kawananakoa Morris, Prince David Kawananakoa's daughter from Princess Abigail, Monsignor Kekumanu and a public works official. When Liliu'okalani Morris saw my mom's genealogy, she said that's it."

On Jan. 3, 1966, Lydia Namahana Taylor Mai'oho was named kahu. Known to everyone as Auntie Namahana, she would serve 28 years, the longest tenure at Mauna Ala. She is legendary and beloved as much for her knowledge of the old ways as for her strong personality and sense of humor. "I wish you could have interviewed her," Kaihe'ekai says. "She was a great lady."

When she retired in December 1994, Gov. John Waihee appointed her son to continue the tradition.

DOWN a steep set of stairs, through an ornate gate opened with a solid brass key that weighs at least five pounds, is the white-marbled Kalakaua crypt, which opened in 1910. To stand in its center, to see in gold the names of King Kalakaua, his Queen Kapiolani, his sister Queen Liliu'okalani, his sister Princess Likelike, his niece Princess Kaiulani, Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaole and several of the Kawananakoa, and two ancient chiefs, to feel the mana gathered there, is both humbling and uplifting.

David Kalakaua Kawananakoa died in 1953 and filled the last space, the end of royalty as it was known in Hawaii for roughly 1,500 years.

Liliu'okalani, who suffered the overthrow of her kingdom by local sugar planters and businessmen, with American blue coats conveniently bivouacked nearby, conceived the idea of a separate Kalakaua crypt, and as she planned it, says Kaihe'ekai, "Her mana'o (intent or mind) was to convert the mausoleum into a chapel so the Hawaiian people can gather and celebrate the birthdays of our kings and queens and high chiefs and high chiefesses and their legacy of aloha to the Hawaiian people."

It is not open for weddings, baby luau or graduation parties.

Other landmarks at Mauna Ala include the Wyllie crypt. "Robert C. Wyllie, originally from Scotland, came to Hawaii in 1840 and served the Kamehameha dynasty for over 20 years," Kaihe'ekai says. "He was the foreign minister of Hawaii and helped Hawaii become recognized as an independent nation among the other nations of the world. For his 20 years of loyal and dedicated service to the nation and to the Kamehameha family, he was given the honor of being the third person placed inside the mausoleum. In 1904, friends of the Kamehamehas built what is now known as the Wyllie crypt. In it are members of Queen Emma's family — her mama, her hanai parents, her mother's sisters, they raised Queen Emma, and John Young II."

At the rear of the property is John Young the elder's grave. "John Young and Isaac Davis, the two kane kea, the two white men, helped Kamehameha create the nation of Hawaii," Kaihe'ekai says.

"John Young with his second marriage marries into the Kamehameha family, the daughter of Kealiimaikai, younger brother of Kamehameha, and John Young and Kaoena become the grandparents of Queen Emma."

The queen planted the centurion-like kamani tree that swoops low over the entrance gate and the two tall kamani at her grandfather's grave.

WHEN it's mentioned to Kaihe'ekai that he could have been born to an island ohana like the Beamers, known for their music, or the Guilds, known for their canoes, or a family of butchers, bakers or ukulele makers, he smiles, nods, seems on the verge of a tear. Admirable, all of those, but…

"I feel so blessed," he says. "I came here for the first time at 2, and the spirits fell in love with me, and I fell in love with them."

Even seven years bedridden in what should have been the most active years of life seem now, from the vantage of Mauna Ala, a blessing. "The way I look at it, I was on my way to juvenile delinquency when I took ill," he says.

In the summer of 1959, at age 14, he contracted pleurisy around the lungs. At the old Kaiser hospital in Waikiki, first he caught pneumonia, then a staph infection. Then osteomylitis grabbed hold of his right hip and ate away at the head of the femur and the socket. Joint-replacement surgery wasn't then what it is now. The result was "a lot of operations … It was a very disheartening time for me. I wanted to go to Kamehameha and play football, my uncles had gone there." He's a big guy, looks like he'd have made a rattle-your-teeth linebacker, but as a result of osteomylitis never suited up and walks with a limp.

"It was in that time my mom was taking me around to various kahuna lapa'au, Hawaiian healers, and ministers… Because Hawaiians, if you got ill there was a process to it, not only in the sense of being cursed, but maybe there was something the family wasn't doing right, or the person. So she was making this search, along with me. They told my mother that my grandfather was protecting me. My mom asked, from what? Just protecting him. There was no other explanation, just the word protection. I've always felt, the family name (Kaihe'ekai) kept me apart from total socialization, it removed me… And through the world of spirits and my ancestors, through my grandfather, it kept me away from this world. It put me in another place, in another realm… I feel a certain grace."

He'd always enjoyed hanging around the grownups as a child, quickly learning that once he "started to hanuhinu them, make trouble, get antsy, they would take you and place you in your room. If you're able to be behave yourself again, you can come out. So I was able to listen to the kupuna (elders), listen to my grandparents talk to different people who came."

He continued listening in the years he lay in bed. Today, the names of ancient kings and queens and long-ago dates roll off his tongue as easily and matter-of-factly as you talking about your sister's wedding or your cousin's graduation. The oral tradition of old Hawaii is alive and well at Mauna Ala.

"I believe it is genetic, in the oral tradition," he says.

MAUNA ALA's aforementioned mystery iwi were discovered by shocked workers when overdue restoration of the chapel began in 1976.

"Trenches were dug along walls, inside and outside, three feet wide, six to eight feet deep, reinforcing steel and cement to shore up the building," Kaihe'ekai says.

"And they find the remains of 19 individuals wrapped in kapa (fabric pounded from coconut bark). People on the inside, their heads faced out. People on the outside, their heads faced in towards the building. Artifacts found with them proclaimed their high lineage … We don't know how many more burials there might be in the middle of the building … In talking with my mom and other kupuna, because Kamehameha V was known as the last chief of the olden type, comparable to his grandpa Kamehameha the Great, we think he placed those individuals around the building to spiritually protect his family inside the building. It's just amazing, mysterious."

After renovation was complete, the mystery bones and artifacts were returned to where they were found.

The iwi of those ancient chiefs will continue their eternal guard when this Kaihe'ekai's son, Bill, also named Kaihe'ekai, 30, a cook at Michel's and an avid skateboarder, hands the family responsibilities to the as-yet unborn, but hoped and prayed for next generation of Kaihe'ekai. Thus will continue the tradition that began on that mysterious night in 1819.

May it always.

The Royal Mausoleum is located at 2261 Nuuanu Ave. It is open to the public 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Monday through Friday, closed on weekends and holidays, except those honoring Hawaiian royalty, such as the upcoming Kamehameha Day (June 11). To schedule a visit, call 587-2590.

---------------------

Here are some of the photographs that were published along with the article.

Top left: Caretaker William Kaihe'ekai Mai'oho

Top right: The Hawaiian flag flies alone at Mauna Ala, photographed with royal palm trees and Mr. Mai'oho. The angle of the photo is clearly intended to make the flag and its tall straight pole "fit in" or "belong" with the palm fronds and the tall straight royal palm trees.

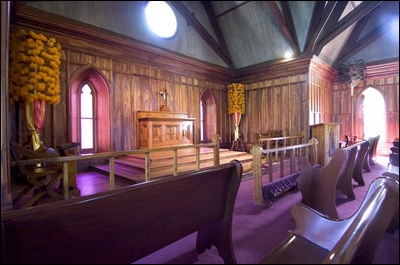

Center: The chapel at Mauna Ala (at first it was the mausoleum containing the bones of the Kings, until they were moved to the newer crypt)

Bottom left: Inside the underground crypt (it is not under the chapel, but is at the end of a staircase going down below bare ground); Mr. Mai'oho tells a group of children about the crypt, while two royal kahili and the Hawaiian flag are visible in the background.

Bottom right: The ceremonial old key to the crypt.

==================

ARTICLE FROM HONOLULU STAR-BULLETIN OF SUNDAY OCTOBER 30 2005 WHICH REPEATS THE CLAIM THAT MAUNA ALA REMAINS "ROYAL LAND UNDER THE HAWAIIAN FLAG" AND THAT WHEN ENTERING THE GATES OF MAUNA ALA "... THE WESTERN WORLD AND ITS LAWS AND CUSTOMS ARE LEFT BEHIND ON NUUANU AVENUE" (The main focus of this Star-Bulletin article is about the failure of the former head of Hui Malama to return a loan of two sacred kapu sticks borrowed under false pretenses several years previously).

http://starbulletin.com/2005/10/30/news/story01.html

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 30, 2005

Mausoleum fears theft of treasures

The caretaker says a Hawaiian group has reneged on a loan

By Sally Apgar

Two sacred staffs topped with golden orbs that for more than 113 years watched over the crypt of the royal line of Kamehameha are missing and believed stolen, according to the caretaker of the Royal Mausoleum known as Mauna 'Ala.

In interviews last week, William Kaihe'ekai Mai'oho, the "kahu," or caretaker, of the Royal Mausoleum in Nuuanu Valley, said he stood on sacred ground of the high chiefs, or, "ali'i," and looked straight into the eyes of another Hawaiian who asked to borrow the pair of "pulo'ulo'u." Mai'oho said he "made a good-faith loan."

That was five years ago and they have never been returned.

Mai'oho said that Kunani Nihipali, then po'o, or director, of Hui Malama I Na Kupuna 'O Hawaii Nei, a controversial group that repatriates native Hawaiian remains and burial objects from museums, wanted to borrow the pulo'ulo'u to guard over bones from Kamehameha lands that their group had reclaimed from the Bishop Museum for proper reburial.

Mai'oho said Nihipali promised to return the pulo'ulo'u to Mauna 'Ala after the bones were reinterred.

"I took his word that he would return them," said Mai'oho, the sixth generation of his family to serve as kahu at Mauna 'Ala. "I told him I wanted them returned because Mauna 'Ala is where they belong."

Mai'oho said he doesn't know if the bones were ever reburied but that he has never seen or heard from Nihipali despite repeated efforts to contact him. In late 2004, Nihipali left Hui Malama and Eddie Halealoha Ayau, a founding member and spokesman of the group, became po'o.

"It is my responsibility to bring the pulo'ulo'u home. I took them at their word. I accept my responsibility that I let them go from Mauna 'Ala. But I never thought they had any hidden agenda. I can see now they had an underlying agenda."

Ayau did not return calls to his Molokai home. Mai'oho and others said that Ayau was often present during visits concerning the restoration.

"This isn't a police matter. It would be very un-Hawaiian for me to go to the police," said Mai'oho, a soft-spoken man who was groomed from early childhood by his grandparents to assume the responsibility of kahu. He is descended from two chiefs hand-picked by Kamehameha I (who is not buried at Mauna 'Ala) to hide his bones after his death from enemies who would want to use the "mana," or spiritual power, from his bones.

"This is not just about stolen items," said Mai'oho, "This is on a much larger, spiritual scale. And I try, but I cannot understand why they did it."

Sitting outside of his small, one-story home on the grounds of Mauna 'Ala last week, Mai'oho said: "It is my responsibility to bring the pulo'ulo'u home. I took them at their word. I accept my responsibility that I let them go from Mauna 'Ala. But I never thought they had any hidden agenda. I can see now they had an underlying agenda."

Mai'oho said that each year he makes several inquiries after Nihipali, but has never heard from him. Even though the loan was made to Hui Malama as a group, Mai'oho said: "This is between Kunani and myself. I want to deal with him directly because it is who I handed the sacred objects to."

The Star-Bulletin has made repeated unsuccessful attempts to reach Nihipali in Hawaii and on the West Coast, where he is believed to be living or traveling. The Star-Bulletin has also tried reaching Nihipali and Ayau through the Native Hawaiian Legal Corp., which represents Hui Malama and was informed of the missing pulo'ulo'u.

Mai'oho said he decided to go public about the loan and alleged theft because in recent weeks he has heard that Hui Malama buried them in a cave.

"I am afraid to say that I don't think they ever intended to return them," said Mai'oho.

Mai'oho said that in 1999 or 2000, the Charles Reed Bishop Trust, which oversees Mauna 'Ala, agreed to restore the two deteriorating Kamehameha pulo'ulo'u, which were made from an iron staff and a copper orb covered in gold and placed with the crypt in 1887.

In ancient Hawaiian culture, pulo'ulo'u were a symbol that royalty was present, according to Mai'oho and other experts. They were carried at the front of royal processions. They were found in pairs outside of a royal house. And if royals decided to take a swim, pulo'ulo'u would be planted in the nearby sand to warn others away.

Typically, pulo'ulo'u contained in the staff or the orb the relics -- bones, teeth or hair -- of ancestral chiefs who watched over the living chiefs or chiefesses. The pulo'ulo'u are believed to hold strong mana. In front of a chief's house, they were sometimes crossed, which forbade entrance to others unless the person chanted their genealogy and business and was permitted entrance. If the pulo'ulo'u were upright, a person could pass through.

The pulo'ulo'u that stand, upright and uncrossed, before the crypts of the royal families at Mauna 'Ala are symbolic, and do not contain relics, but are believed to have strong mana, said Mai'oho.

Several appraisers contacted by the Star-Bulletin said it is almost impossible to estimate a commercial price for the pulo'ulo'u because few if any have ever been sold and they are such a rare, one-of-a-kind item.

In about 2000, Nihipali and George "Billy" Fields, a Big Island mason who often does work for Hui Malama, were hired for the restoration of the pulo'ulo'u, according to Mai'oho and Lurline Naone- Salvador, who worked for 29 years at Kamehameha Schools and has worked closely on restorations at Mauna 'Ala.

Naone-Salvador confirmed Mai'oho's statement that Nihipali and Fields said the originals were too badly deteriorated to be refurbished and a new pair should be made. The day they installed the new ones at the crypt, Nihipali asked to borrow the old ones.

Mai'oho said Nihipali explained how Hui Malama had taken possession of ancestral bones from the Bishop Museum and that they were stored at his Pupukea home until they could be properly reinterred. He said some of the bones were from Kamehameha lands and that he wanted the pulo'ulo'u to guard over them.

"I loaned them because there was a connection with Kamehameha," said Mai'oho. "But I told him I wanted them back because they belong here and I would either find someone to refurbish them or I would bury them behind the Kamehameha crypt."

Naone-Salvador agreed with Mai'oho, "It was definitely a loan."

"If they put the pulo'ulo'u in a cave, it is like blasphemy," she added.

Naone-Salvador said that in late 2000, she visited Nihipali at his Pupukea home. She said that behind his house he had built a wooden shed lined with shelves that held the bones repatriated from the Bishop Museum. When she opened the door of the shed, she said, "I saw the pulo'ulo'u with my own eyes.

"When I saw the pulo'ulo'u, I said: 'Why are they still here? Why are they not back at Mauna 'Ala?'

"It wasn't like a confrontational conversation with Kunani. It was casual. And Kunani said he had them until the iwi (bones) were buried."

Not long after, Naone-Salvador said she had a falling out with Hui Malama. "It has to come back because it is meant to be here. And if it can't be used, it should be buried here and not removed," she said.

Fields also told the Star-Bulletin that "Hui Malama borrowed (the pulo'ulo'u)."

"And it's like Kunani just vanished,' he added.

Fields noted that he is not a member of Hui Malama. "I am just a hired gun."

In a recent affidavit he filed in a federal lawsuit over the disposition of items from Forbes or Kawaihae cave, Fields testified that he has performed "various masonry, welding and construction work in conjunction with over 50 repatriations" that Hui Malama has conducted to rebury native Hawaiian remains and burial objects since 1990.

Mai'oho said the way Nihipali borrowed and never returned the pulo'ulo'u is similar to his understanding of how Ayau allegedly borrowed 83 sacred artifacts known as the "Forbes collection" from the Bishop Museum as a "one-year loan" in February 2000. The items, originally taken from the Kawaihae or Forbes Cave on the Big island, were not returned.

Ayau has said the items were resealed in Kawaihae. He has repeatedly defended Hui Malama's actions, saying that the items were originally stolen from the ancestors in 1905 by David Forbes and two others, and that the museum knew that it was buying stolen goods. Ayau has repeatedly said Hui Malama reburied the items to honor ancestors and right the wrongs of the 1905 theft.

Hui Malama also claims that the Kawaihae items were properly repatriated under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, a federal law that governs the reclamation of native Hawaiian and American Indian remains and artifacts from museums. Some of the other 13 claimants to the Forbes items say they did not get a fair voice in the disposition of the items when Hui Malama reburied them.

Last March, the NAGPRA Review Committee came to Honolulu to hear testimony on the case. When asked by the committee what he thought a loan meant, Ayau told them, "It was a vehicle for repatriation."

He also told the committee that neither Hui Malama nor the museum staff expected the items returned. The committee, which has only advisory power, ruled the repatriation was "seriously flawed."

Today, Kawaihae cave is at the center of a federal lawsuit that seeks the retrieval of the 83 items so that 14 native Hawaiian claimants may have a voice in their final disposition. The suit was bought by two claimants: La'akea Suganuma, a practitioner of lua, which is a form of ancient Hawaiian martial arts, and Abigail Kawananakoa, a Campbell Estate heiress and descendent of the royal Kalakaua line. The two argued that Hui Malama disregarded the rights of other claimants when they reburied the items.

Suganuma, who has long been at odds with Hui Malama, said that if the taking of the pulo'ulo'u is true, it "is the height of arrogance. This is total disrespect for the culture and the ali'i to just take these things. It is so disrespectful."

Mai'oho compared his loan to Hui Malama to the Bishop Museum's loan of the Forbes items: "It's what Hui Malama did at the Bishop Museum with the Forbes cave items. But to come and do the same thing at Mauna 'Ala, I just don't understand."

"This is far worse than taking from the Bishop Museum," he added.

Mai'oho said that when someone crosses the threshold of the gold-tipped gates of Mauna 'Ala, they come onto 3.5 acres of royal land under the Hawaiian flag. He said the Western world and its laws and customs are left behind on Nuuanu Avenue and that Hawaiians can relate to one another completely on Hawaiian terms.

"If you are Hawaiian, your word is life and death, especially here," said Mai'oho. "Here, on Mauna 'Ala, we can be completely Hawaiian with one another."

He noted that everything that is of Mauna 'Ala belongs there, including the pulo'ulo'u.

"Even the dirt is consecrated here," he said. "It is blessed and it isn't taken from here."

** Note from Ken Conklin: For extensive information about Hui Malama, its religious theory, its role in the theft of the ka'ai from Bishop Museum and its role in the Forbes Cave controversy, see:

https://www.angelfire.com/hi2/hawaiiansovereignty/nagprahawaii.html

For information about the lawsuit against Hui Malama regarding refusal to return artifacts from Forbes Cave "borrowed" by Hui Malama from Bishop Museum (lawsuit ongoing at the time the Star-Bulletin article about Mauna Ala was published), see:

https://www.angelfire.com/hi2/hawaiiansovereignty/nagprahawaii2005.html

==========================

ARTICLE FROM HONOLULU ADVERTISER OF FEBRUARY 22, 2006 REGARDING BILL IN STATE LEGISLATURE TO PROVIDE DEDICATED FUNDING FOR MAINTENANCE OF MAUNA ALA

http://honoluluadvertiser.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20060222/NEWS23/602220365

Honolulu Advertiser, Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Mauna 'Ala showing its age

By Gordon Y.K. Pang

The resting place for Hawaiian royalty would get a dedicated source of state revenues under a bill moving through the state Legislature.

A number of Hawaiian organizations and individuals are supporting the plan to designate a funding source for repair and maintenance at Mauna 'Ala, the Royal Mausoleum, in Nu'uanu. But officials with the state Department of Land and Natural Resources Parks Division, which operates the site, counter that the bill is unnecessary and could siphon funding from other upgrade efforts.

For many Hawaiians, Mauna 'Ala is hallowed ground. Initiated by Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma, the 3.5-acre site overlooking downtown Honolulu includes the tombs of every member of Hawaiian royalty with the exception of Kamehameha the Great and King William Charles Lunalilo.

The birthdays of royalty are still celebrated at Mauna 'Ala by Hawaiian civic clubs and other organizations. Civic club members and boarding students from Kamehameha Schools also go there on weekends to clean the chapel or clear fallen branches.

An annexation resolution adopted by Congress in 1899 stipulates that Mauna 'Ala must be kept as a mausoleum for Hawaiian royalty and never be considered "for sale, lease or other disposition."

[** Note from Ken Conklin: Gordon pang is mistaken. That resolution was dated May 31, 1900, a month after the Organic Act was passed by Congress on April 30, 1900 to implement the Annexation of August 1899]

"Mauna 'Ala's such a special place," said Stacy Rezentes, director for the Charles R. Bishop Foundation, a nonprofit organization that provides some support to the landmark site. "It's important to Hawaiian people, and to people that call Hawai'i home. The ali'i who left so much to us are buried there. We really need to take care of them."

Last summer, more than 10,000 people who gathered at 'Iolani Palace in support of Kamehameha Schools' admissions policies that offer preference to students of Hawaiian heritage marched two miles to the site to pay respects to the schools' founder, Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop.

DETERIORATING CHAPEL

Queen Lili'uokalani converted the original mausoleum building, completed in 1865, into a chapel after the caskets were moved into tombs and crypts below ground. Nearly 150 years later, despite a decade of extensive state-funded renovations that began in the mid-1970s, the chapel building is showing its age.

Among other things, there are cracks in both the interior and exterior plaster, and the drainage system on the chapel roof needs to be replaced.

There's also a public restroom facility, constructed during the 1950s, that needs upgrades to meet Americans with Disabilities Act standards.

Toni Lee, president of the Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs, compared the restroom area to an outhouse. "You would never put an ali'i in one of those restrooms," Lee said.

A March 2005 study funded by the Charles Reed Bishop Trust concluded about $1 million is needed for capital improvements, major repairs and landscaping over the next three years.

Among other major projects identified by consultant DLR Group: repaving of a circular road through the site, restoration of the perimeter rock wall, and replacement of the roof of the Kalakaua Crypt. Also, a large kamani tree that looms prominently over Mauna 'Ala that was planted by Queen Emma in honor of her husband is in need of a support system for its lower branches.

MORE LANDSCAPING CARE

William Mai'oho, Mauna 'Ala's curator since 1995, said the site's last full-time groundskeeper retired in 2000. The upkeep is now covered about three mornings a week by two groundskeepers based out of Kaka'ako Regional Park, he said.

Mai'oho is descended from a secession of Mauna 'Ala curators who trace their genealogy to one of the two keepers of Kamehameha the Great's secret burial site. He said while the regular state maintenance coupled with the volunteer work is keeping the site passable in appearance, it would be nice if Mauna 'Ala once again had a dedicated groundskeeper.

Mai'oho said he understands the state's ongoing budget constraints, but noted more attention and care must be given to landscaping — beyond sweeping and mowing — and he hopes additional funding can be tapped for those needs.

Sen. Colleen Hanabusa, D-21st (Nanakuli, Makaha), chairwoman of the Judiciary and Hawaiian Affairs Committee, said that's why she introduced Senate Bill 1294, which seeks to designate a percentage share of all ceded land revenues to repair and maintenance at Mauna 'Ala.

The bill specifies that the share is not to come from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs' portion of ceded land revenues, but from the overall amount received by the state.

Hanabusa said Mauna 'Ala supporters are tired of going before state lawmakers to ask for one-time capital improvement projects and competing with other DLNR funding priorities. If the bill gets the Legislature's backing, responsibility over Mauna 'Ala could be shifted to OHA or the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, Hanabusa said.

"The problem with it being under DLNR is it has to wait in line with everybody else," she said.

Hanabusa said she left the amount blank in the bill because DLNR has not responded to requests about operational costs for the site.

DLNR said annual expenses are about $90,000. The amount includes the salaries for Mai'oho and groundskeepers, utilities and related maintenance fees.

DLNR officials oppose the Senate bill, contending that it is unnecessary and could gobble up funding needed for other more pressing upgrades.

"Obviously, this is an important place that we need to make sure is protected and maintained," said DLNR Director and Land Board Chairman Peter Young. But, he added, "The process may not need the dedicated funding. It may need the continued effort on our part as well as our partners in making sure the area is protected."

Dan Quinn, DLNR parks administrator, defended the upkeep of the site.

"There's certainly work to be done, but it's not like it's been neglected," Quinn said.

In addition to the decade-long renovation to the chapel that wrapped up in the mid-1980s, the state replaced the curator's residence in 2000 and renovated the Kalakaua Crypt in 1992-93, according to DLNR information.

The Bishop trust, which is related to Kamehameha Schools but is funded by a separate endowment, restored the wrought-iron front gate in 1985 and paid for repairs to the chapel and three monuments in 1993. Four years later, the Queen Lili'uokalani Trust restored the John Young Crypt.

DLNR, Peter Young said, is now working with the Bishop trust, civic clubs and others to draft a priority list for the projects identified in the recent study.

$1.4M FUNDRAISING GOAL

A private fundraising effort called Malama Mauna'ala has started under the leadership of the Bishop trust; Kamehameha Schools; and Hawai'i Maoli, an arm of the Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs. Its goal is to raise $1.4 million, according to Rezentes of the Bishop trust.

Rezentes said the combination of dedicated state funding and private-source funding would help ensure the aging Mauna 'Ala is never in disrepair.

Hanabusa said she does not buy the argument that Mauna 'Ala is not in top condition because state officials are coping with budget constraints.

"It shouldn't be like that, not for who's resting in that place," she said. "It just seems like such a sacrilege for it not to have been kept in pristine condition. And it's not a Hawaiian issue, it's just an issue of respect for the history of this state."

ABOUT THE BILL

SB1294 would require the state to allocate a portion of ceded land revenues for the repair and maintenance of Mauna 'Ala, the Royal Mausoleum. The site's funding now comes from the Department of Land and Natural Resources' general operations budget. For now, the bill does not specify a percentage of ceded land revenues that would be dedicated to Mauna 'Ala. Currently, the state allocates about $90,000 annually for a curator, two part-time caretakers and related maintenance fees.

WHO'S INTERRED AT MAUNA 'ALA

Six of the eight monarchs of the Hawaiian Islands, from King Kamehameha II to Queen Lili'uokalani, as well as other members of the Kamehameha and Kalakaua families and several of their closest acquaintances, are interred at Mauna 'Ala, the Royal Mausoleum, at 2261 Nu'uanu Ave.

The grounds and chapel are open to the public, 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Monday through Friday. The grounds will also open on March 26 in honor of Prince Kuhio Day and June 11 for King Kamehameha Day.

The Kalakaua Crypt is closed except on the birthdays of those entombed there. There is no charge.

** The following were two of the photos published with the Honolulu Advertiser article of February 22, 2006:

The interior of the chapel at Mauna 'Ala, the Royal Mausoleum, in Nuuanu includes koa wood paneling and Douglas fir pews.

Map showing the layout of buildings and grounds:

==================================

NEWS REPORT ON KITV TELEVISION ON OCTOBER 21, 2015, REGARDING THE THE NEWLY CONFIRMED CURATOR OF MAUNA ALA, WHO IS THE SON OF THE RECENTLY DECEASED CURATOR AND THUS CONTINUES THE FAMILY'S TRADITION OF SEVERAL GENERATIONS AS CARETAKERS OF THE BONES OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM'S ROYALS

http://www.kitv.com/news/new-curator-of-the-royal-mausoleum-at-mauna/35973176

KITV News, Oct 21, 2015

New Curator of the Royal Mausoleum

HONOLULU -- William "Kai" Bishop Kaihe'ekai Maioho has been chosen as the new Curator of the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna 'Ala on Oahu. He starts October 21, 2015.

Kai will be the 15th curator of the Royal Mausoleum, established in 1865 as the final resting place for the ruling monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaii, their families, and close advisers. Kai replaces his father, William "Bill" Maioho, who passed away earlier this year while serving as Curator.

"The department greatly appreciates Kai Maioho's steadfast commitment to the Royal Mausoleum and his willingness to assume responsibility for maintaining the sanctity of the grounds," said DLNR First Deputy Kekoa Kaluhiwa. "He has demonstrated his detailed knowledge of the Mausoleum and its grounds and of the efforts needed to preserve the site and support people coming to Mauna 'Ala to honor the royal families."

==================================

Send comments or questions to:

Ken_Conklin@yahoo.com

GO BACK TO OTHER TOPICS ON THIS WEBSITE