The greatest female athlete in the world is about to spend the next eight and a half hours…getting a new hairdo. Hey, a diva’s gotta do what a diva’s gotta do. “I think I should go dark now,” Serena decides, dunking her head into the sink. “I don’t want to be blonde anymore. Blondes get taken advantage of.”

Serena Williams bursts out laughing. It’s the laugh of a woman who never gets taken advantage of—and is never unaware of the power of being Serena. “You notice how everyone went blonde after I went blonde?” she purrs.

She is sitting in her bathroom in Palm Beach, wearing a lavender robe and big fuzzy purple bedroom slippers with her hair full of goop, her face exfoliating—and 242 Harry Winston diamonds wrapped around her wrist. “They made this just for me,” she says, flashing from beneath her bathrobe the eye popping bracelet that got almost as much attention at the Australian Open as her history-making fourth consecutive Grand Slam title, a.k.a. the Serena Slam. She smiles serenely at her image in the mirror. “I love getting stuff for free,” says Serena. “I am the queen of free.”

She starts to sing. “ ‘Diamonds are a girl’s best friend….’ Marilyn,” she divulges, “is my role model.” She has recently been on a Marilyn Monroe binge, watching all her movies back-to-back. For inspiration. And not just because Serena has already decided what her second act will be—she is going to become an actress. “I love her style.” It seems a most, well, incongruous role model for the fiercest, baddest female athlete on the planet, but really it’s not so off the wall. Like Marilyn, underneath the in-your-face, world –by-the-balls façade, Serena—who, its easy to forget, is only 21—just wants to be a girl.

“Here, try this,” says Serena, spritzing Lolita Lempicka perfume on my one wrist and Chance by Chanel on the other. We will eventually sample every one of the two dozen or so scents displayed in her bathroom. “Most of these are my daywears,” explains Serena. You want the nighttime stuff, make yourself comfortable.

She is perched on a dainty velvet vanity stool, talking to her reflection in the enormous mirrors that line her favorite room: Serena’s Bathroom. This is the same woman who wrote in her official Women’s Tennis Association bio that her “favorite place to visit” was “the mirror in my house.” Serena’s Bathroom is an over-the-top affair of white marble, gold fixtures, a tub that could fit four, and more beauty products than the first floor of Bendel’s. “I’m addicted to hair products,” she says. And lotions and scrubs and perfumes and makeup and four drawers full of hair extensions. “I got so much stuff I could sell it on the street.”

“How dark do you want to go?” asks her pal and stylist, the lovely Linda Mayhand-Parish, who from 2:00PM until 10:30PM will twist, braid, unbraid, rebraid, relax, tie, dye, sew, and otherwise do things to Serena William’s head that you don’t even want to know about. “Everybody in Hollywood is doing it,” says Serena.

She has just returned from Melbourne, where she cemented her role as the queen of sports, kicked her sister’s butt in the finals, and generally freaked out Aussies. In other words, the usual. Now she just wants to exfoliate.

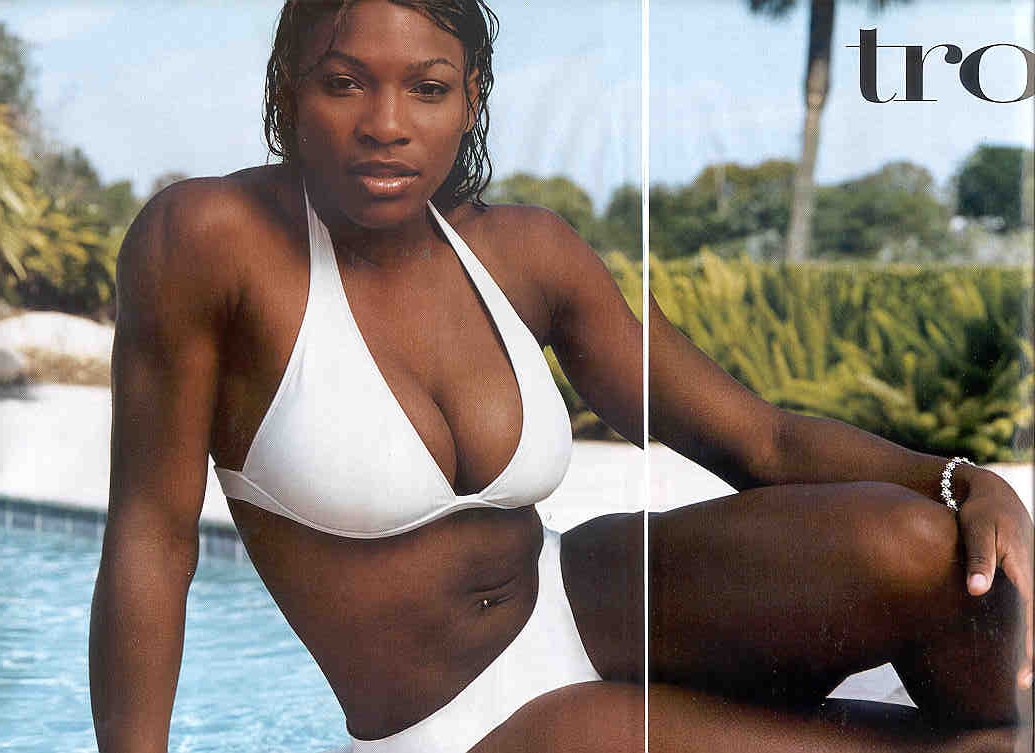

“This is the best stuff for your skin,” she says, reaching for a jar of Origins Ginger Body Scrub. “Once or twice a week,” she instructs. “You will be alarmed at how smooth it leaves you.” She offers as exhibit A her own world-renowned gams, which are in fact “like butter.” (Her other secret: “the Venus razor,” by Gillette.) “I love to take care of my body; I really do,” she coos. Serena loves Serena’s body. As she once announced to the press, in what was certainly a first in women’s tennis, “I’m really sexy.” Last month, in a typical display of her near-pathological self-confidence, bless her, she finagled her way into the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue by calling up and offering her services.

“Would I change anything?” she asks. She sizes herself up in the imposing mirror—the Marilyn breasts, the J.Lo butt, those thighs. Nope. “I think as a woman you have to be happy with what you have. The bottom line is, you can’t change it. Well, let me take that back. You can!” But this particular woman won’t. “Although,” she says, “if I had a A cup, I would get a boob job. But I would just enlarge them to, like, a B. I mean, I’m a D.” She considers this. “Yeah, it’s great. When you’re not playing.” Is it an issue on the court? “I’ve had some back problems.” But more important, “I just can’t wear the cute little..well, I guess I do wear the cute little outfits, but they can’t be as cute as I want them to be. I guess I wouldn’t mind being a C,” she allows. But enough about boobs.

“Here, take one of these,” she says, stuffing an Origins jar into my purse. “I have a friend who works there, so I get them for free.” She winks. “I have a friend that works everything. Why buy when you can get it for free?” It’s not her fault that people keep giving her stuff—to wear in public.

To illustrate, she takes a break from the Hair Project and shuffles down the marbled hall in her big fluffy purple slippers to her closet. Suffice it to say you have not lived until you have been in Serena Williams’s closet. The size of a studio apartment in New York, it is an explosion of color and fur, organized by Serena herself, who “hates mess” and therefore spends her downtime rearranging racks and racks of her on-and-off court wardrobe and accessories. There is the fur-coat section (featuring two new, delicious pieces that Venus bough for her on sale in Russia), the other coat section(“I got this one for free from Calvin Klein”), and the bag section. “I’m crazy about bags, but I haven’t bought one in three months. I was buying a bag a week. I had to stop. And every time I buy one, I must have the matching wallet. Here’s a Fendi that I never ever wore…” We move on to the sneaker section (the nice people at Puma, who pay her about $2.5 million a year to wear their shoes and togs on the tennis court, send her a new shipment every few months), the gowns (she designed many of them herself, after watching Joan Crawford movies), and an entire wall of shoes. “I’ve gotten really into shoes lately,” says Serena. “I recently went to the Bergdorf Goodman’s and got me some Marc Jacobs.” Though her feet are a muscular size 10, her taste runs toward the daintiest, strappiest, highest Manolos and Giuseppes. “I wore those to the Wimbledon Ball,” she says dreamily.

Hanging prominently by the door is her latest acquisition, which showed up in the mail today: a white mink coat. Serena slips it on, strikes a pose, and for a moment look like Marilyn on the grate, but warmer. She admits that this she actually paid for herself. “But then they gave me these!” she says excitedly, whipping out a pair of white mink “leg muffs” that the owner insisted she take—and was duly rewarded when she wore them straight into a flock of paparazzi, who love to chronicle her Madison Avenue purchases. “Alleged purchases,” she corrects. “Like, I never bought a half-million dollar necklace,” she gripes, referring to a recent news flash in the New York Post “That doesn’t even sound like me. I’d be out of my mind to do that!” She laughs. “Now, I did borrow a half-million dollar necklace…”

Serena admits that she used to have a bit of a shopping problem. Particularly when it came to the Internet. It was something of an occupational hazard for a barely 21-year-old who travels the world for tournaments and spends every night alone in a hotel room. With zillions in the bank. “I used to be an addict,” says Serena. “You’re in Paris with nothing else to do, and the next thing you know you’re on-line and the next thing you know you’re buying books.” Though books were the least of her problems. “I had to go to a twelve-step program to stop shopping,” she says, laughing. “Shoppers Anonymous.” She is joking, but only about the actual program. Serena’s twelve-steps were self-imposed—like everything else in her life. “I had to,” she says.

In fact, Serena—give or take a white mink coat now and then—is, as she puts it, “very frugal. Too frugal.” Especially considering she set a new record for prize money earned in single season: a few bucks short of $4 million in 2002 (and that’s not including endorsements); she and Venus combined bring in well over $20 million a year. But they don’t have hired help—save for a cleaning lady who comes in once a week “except when we’re away,” which is most of the time—in their 7,500-square-foot-house. In the several days I spent at home with Serena, there wasn’t a maid, a cook, a driver, not even a secretary to answer the phones. “I clean that house,” says Venus. “Oh, this child can clean up!” says their mother, Oracene, proudly. “I like mopping,” says Venus.

The house Serena and Venus share—each has her own wing—is an airy, palatial spread with 30-foot-celings and white marble floors that the sisters designed together. It is filled with things they have acquired on their travels; every time they play a tournament, they get something for the house.: chandeliers from Austria and Italy, oil paintings from Russia and Australia, candlesticks from Belgium.

The house is also on one of the more beautiful golf courses in Palm Beach. “My dad’s teaching me to play,” says Serena, which should probably scare the crap out of Tiger Woods. But so far the mythic Richard, the daddy that started it all, has had a lot less luck in teaching the girls golf. “I have a good drive,” says Serena. “It’s just doesn’t go in the right direction.” And besides, she has a beef with the club. “I would like to say,” says Serena grandly, “that they tried to charge me $8,500 to be a member. Uh-huh. Knowing I could bring in a lot of people if they give me a membership for free.” So did she join? Dumb question. “No. I didn’t. I told them I simply could not afford it.”

“I’m trying not to use the word cheap. She’s very conservative with her money,” says Diondria Thomas, Serena’s best friend since the fourth grade, who, conveniently, also manages an Origins store in L.A. From which regular “care packages” are shipped to the world champion. (On one of the days we visited , a big box from Origins was sitting at the front door.) “But when she comes to L.A. She likes to come to my job. She’ll hang out at the store for, like, hours, and sell products to the customers.” She’ll also wrap them and ring them up; she’ll even give them an autograph with purchase if that’s what it takes to make a sale. “Last time she was here, she had nothing to do, so she came in for like four hours and helped with inventory.”

Diondria says that one of their favorite things is to sneak off to Las Vegas, where they check into the Venetian and play a game called Flip-Flop. “It’s a nickel slot,” says Diondria. “We’’ sit there till like three in the morning, playing the nickel slots.” It’s the only place, she says, that Serena isn’t recognized.

Does she ever wonder why Serena is so frugal? “You know, I asked her that. I said, ‘Serena, why are you so cheap?’ And she said, ‘Because I guess I never had anything.’” Diondria pauses. “She doesn’t forget where she comes from, you know what I mean?”

That would be Compton, the poor neighborhood in south-central L.A. that is best known for the Williams sisters and for the race riots of 1992 that followed the Rodney King verdict. By now the tale of the two poor little black girls who rose from the “ghetto” to dominate the big bad white world of tennis has been told so many times it sounds like an urban fable. According to Serena, some of it is. “They try to make our story like we lived in the projects,” she says, rolling her eyes. “It was a really small house. But we didn’t live in ‘the projects’. Everything wasn’t easy. But at the same time, it’s not like I had to starve. We were taken care of, spiritually as well as physically. And both our parents worked.”

“Like Martina Hingis? She had to live in a car for a while, but they don’t ever talk about that!” she says, laughing. (Hingis’s people say it most definitely wasn’t her.) And that one Russian girl, “her mom, they had to sell their TV just to buy the girl a racket. We didn’t have to do nothing like that.”

The actual story is incredible enough. How her father, Richard, who had a security company that guarded strip malls at night, was watching TV one day and happened upon a women’s tennis match. He didn’t know a thing about tennis. But “he was watching this girl playing,” as Serena tells it, “and she won a tournament, and she won more than he made his whole year [$30,000], in just one tournament. And my dad was like, OK. You know, you want your kids to be better than you. So what he did was, he went out and got a bunch of tapes on how to play tennis and he taught himself, and he taught my mom,” who was a nurse. “And then they taught us.”

There are five sisters. All of them learned, on a public court in L.A.—where, legend has it, they played on broken glass with drug dealers lurking and the occasional gunshot ruining their serve. (“I’m sure that it was,” says Serena, clearly bored with this topic. “But when you’re a kid on a court, it’s like any court.”) In any event, Richard and Oracene, as they’ve said many times, knew pretty early on the youngest two, Venus and Serena, would become not only pros but the two best players in the world one day. As Serena Roberts in The New York Times put it, it was “a scenario as improbable as one set of parents raising Picasso and Monet.”

The parents also correctly predicted that Serena would emerge as the better player. What no one imagined was that the two of them would be so far ahead of the rest of the pack—no one even comes close in terms of raw power and speed, the secret to both their games. “So why Serena? Why now?” as Martina Navratilova wrote recently in Tennis. “The biggest reason, I think, is that she wanted it,” she says. “You could see it in her eyes and her demeanor…and take it from me, she’s the biggest hitter the game has ever seen.”

Serena downplays what it’s been like to conquer one the whitest, blondest sports in America. But Oracene will tell you like it was. “The tennis community,” she says pointedly, “didn’t really want them there. Then it was like, ‘OK, one we can accept, but two?’”

Oracene says the more her daughters had to earn their respect, the more she would remind them “how important sister love is.” It is one of the most pondered questions in sports how Venus and Serena can destroy each other on the court and still have sister love. This they find hilarious. “I am sooo sick of those questions,” says Serena, launching into a mocking imitation of the press: “ ‘What does it take to beat a Williams sister? How does it feel playing your sister?’” How does it feel? As Oracene always instilled in her girls, “This is just a game. You have a winner and you have a person that’s not going to win that day. There are other things.” Which is the best way to explain how they really feel about beating each other: A real crisis, says Serena, is not playing your sister. A real crisis is not playing your sister because she doesn’t make it to the finals, because then it would be somebody else. That they really hate.

The dynamic between the two is not much different from when they were little girls. Serena grew up not only idolizing Venus, “I wanted to be Venus. I did everything Venus did. Everything. And still to this day, I do what she does.” When they were children, says Serena, “it got so bad that when we’d be in a restaurant they’d make me order first.” But even that doesn’t work. “When she ordered, I’d change mine to whatever she had.”

They grew up as devout Jehovah’s Witnesses, and still are. Both of them go to the Kingdom Hall as often as three times a week for meetings. Oracene taught her girls to love the Lord—and not take any crap. She also taught them to never depend on a man. It was a curious lesson in a family where the father methodically determined their fates. “But I never believed in Santa Claus,” as Oracene puts it. “I’ve always been real about men with my girls. I never gave them this fantasy about marriage and having a white dress on.”

In February 1999, as reported by Sports Illustrated, Oracene “went to a hospital in Palm Beach…for treatment of three broken ribs.” She also reportedly told the police, “I know you know what happened, but I’m fearful for my daughters’ careers.” (Richard Williams denied the assault allegation.)

The famous Williams parents are now divorced. Oracene (now Oracene Price) managed to keep the news out of the press for nearly a year. Their parents are still their only coaches, and they both continue to travel with the girls to tournaments—though never together anymore. “In terms of the girls, we have a relationship,” says Oracene when asked if they have a good one. “He knows his part and I know mine.” But in terms of how the two of them get along now, she says, “once I’m done with it, I’m done with it; I don’t have anything to say to you. Because if you don’t know how to treat me or talk to me then, we don’t have anything to say now.”

Serena insists she’s “fine” with the divorce. “It’s not my marriage,” she says. As for her own dating situation, she is “off the market.” According to Diondria, this is a career move. “When she is on the market, she’s not as focused on her game.” Diondria also says Serena loves “tall, dark black men.” But Serena doesn’t want to talk about that. “I like what Venus says,” says Serena. Venus: “If he don’t got it, don’t let him take it from you.”

Five hours into the hair project, it’s getting dark in Palm Beach, and Serena’s back is killing her from sitting in the little velvet stool. She’s still on Australia time and doubly exhausted from the six-hour morning workout on the practice court with her father that preceded the onset of the 8 ½-hour hair extravaganza. But she has to be in Paris in two days to win another tournament, so the Entire Serena needs to be ready—including her hair. Linda suggests that they move to a more comfortable part of the house, and Serena, her eyelids heavy, nods and shuffles toward the TV room, with Jackie, who’s also getting tired, following at her fluffy heels.

On the way, she stops in the kitchen and peers into the refrigerator, lifting out a box of leftover Popeyes fried chicken. “Want some?” (“I don’t diet,” she says. “Last time I was on a diet, I gained five pounds.”) Usually, Venus makes dinner, says Serena. “Venus does everything. She cooks for me, she takes care of me.” But tonight they’re supposed to go out( an event that will never happen, because Serena’s hair won’t be completed in time.)

As she pops her Popeyes chicken into the microwave, Venus comes home, carrying an armload of fabrics and photographs of beds and coffee tables. “I found some you’ll really like,” she tells her sister. Venus—the world champion till her little sister beat her down to number two—has already lined up her post-tennis career, as an interior decorator. Her first project was the house they live in; her next is Serena’s new apartment in L.A., where the star plans to pursue her next career, the acting thing.

“Oh, this was all part of the plan,” says Oracene, who has just shown up at the house with her caffeinated Chihuahua, Rocky, in tow. “You know, you have, OK, maybe ten years of you’re blessed, if you stay healthy. Maybe more; depends on how you wanna do it. But what you gonna do afterward?” Her daughters, she says, well, “they are not gonna be on the TV announcing tennis games. Uh-uh. They will not do that. No, they’re gonna plan their life.”

Though at the moment, all they seem to want to do is watch SpongeBobSquarePants, their favorite show. Long, tall Venus, in tight black leather pants, drops into one of the enormous butterscotch-leather chairs in the TV room. Serena, still in her lavender robe, plops into the other—while Linda continues the work in progress that is Serena’s hair. “Everyone in Hollywood does this,” Venus notes. All around them, meticulously displayed on rows and rows of glass shelves, are the dozens and dozens of trophies they’ve earned, gleaming in silver and crystal. Well, most of them. They have so many they have run out of room and are using some as flowerpots in the dining room. “Everywhere I look, I see another one of these trophies,” says Serena. “I keep telling Venus, ‘This has gotta stop.’ We don’t have room for any more.”

For a while, the sisters toss the remote back and forth, waiting for SpongeBob to come on. But eventually, they both nod off. Even Jackie falls asleep. (Though Linda is still doing Serena’s hair.)

It’s close to midnight before Serena, who is now (finally) a brunette, with hair to her waist, pads down to her bedroom, at the very far end of her wing. She sleeps in a massive mahogany four-poster bed that Venus helped design for her, with just a few mementos scattered around the room. “This is my favorite,” says Serena, pointing to a black-and-white photograph of her with her mother and sisters, taken when she was five, that she keeps on the table closest to her pillow. “I used to love that purple dress,” she says softly. The other prominent thing in the room is her most recent silver cup from the U.S. Open. “Another one,” says Serena with a sigh. But she still goes to bed with her trophy.                    |