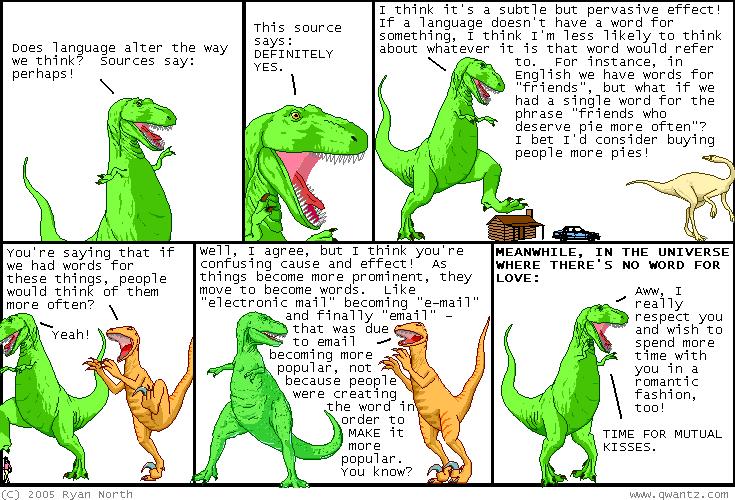

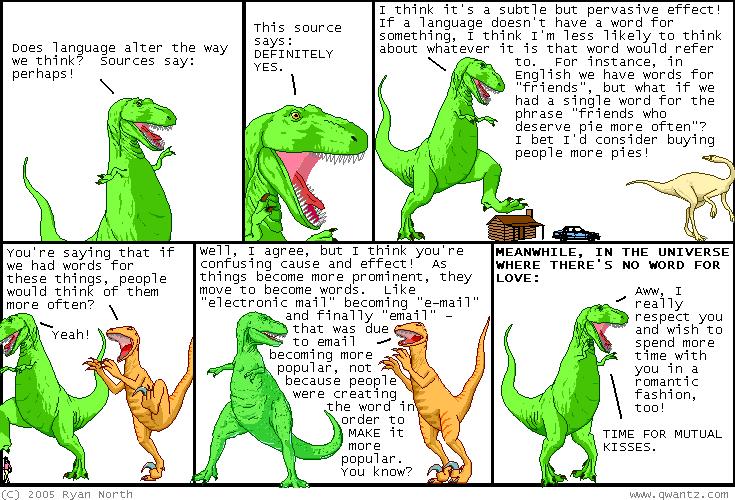

Figure 1: (Dinosaur Comics, 2005; North, 2014)

Introduction

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis established by anthropological linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin L. Whorf proposes that language inextricably shapes our world by determining the categories of our perceptions. What this means is that language projects itself on both reality and thought by either interpreting or influencing every day events and “social-cultural systems” (Lucy, 1997). The interpretations of our realities are thus not universal, as our language shapes our cognitive processes in establishing mental representations. Our language determines how we think, which is very much specific to our cultures. A more moderate stance is often taken called linguistic relativism, where language influences categories of thought, rather than completely determining it. For example, Indonesians conceive of human gender in five categories; comparatively, English categorizes human gender into two categories: male and female. This illustrates how language shapes how we perceive the world: concepts based out language categories manipulate the understanding of gender as being pentamerous in the Indonesian culture, while English shapes gender as a binary concept (Johnstone, 2008).

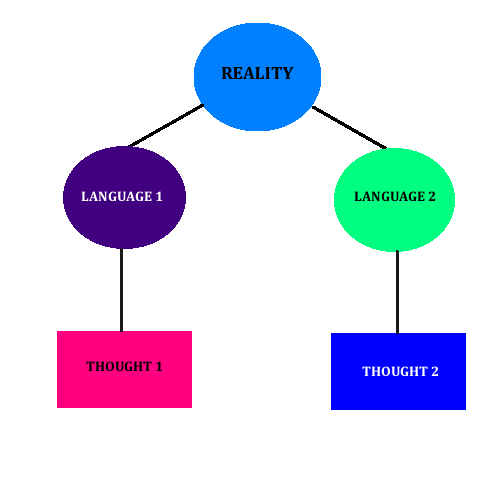

If an individual grows up speaking two or more languages, the way in which that person categorizes the world around them is highly variable depending on whether or not the categories of these languages overlap and differ in certain concepts. The speaker would thus have multiple perceptions of one concept, as each language’s categories would shape the perception of these concepts. For example English speakers “tend to analyze reality into objects, whereas Hopi speakers tend to talk about events” (Johnston, 2008). It would be hard for an English speaker to alter their cognitive process of representing reality as an object and instead talk about an object, such as tree, as a progressing botanical event.

Figure 2: Diagram of a bilingual’s interpretation of reality based on the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. (Ramsden, 2014)

A video by Heidi Arnold offers a clear and comprehensive view of this hypothesis, which can be found here.

Empirical Approaches

The theory of linguistic determinism is a highly controversial idea, lacking in empirical evidence. In John A. Lucy’s article “Linguistic Relativity” he delves further into the proposal of linguistic relativism, highlighting empirical approaches in contrast with more recent methodological approaches. Lucy explains that language can act as an influencer on three levels:

- On a semiotic level: “any natural language at all may influence thinking”; the symbols of the language directly project onto the speaker’s way of thinking;

- On the structural level: whether different language systems affect the speakers conception of reality;

- On the functional level: the way we use language may directly influence our cognition (Lucy, 1997).

A structured-centred approach focuses on the differences between specific languages by extrapolating on the structure of meaning in each individual language and the interpretations of reality embedded within them (Lucy, 1997). Whorf and Sapir used the structured-centred approach with respect to temporal markings in the English and Hopi language as mentioned in the example earlier (Lucy, 1997).

In Lucy’s recent approach, ethnographic observation coupled with thorough appraisal of individual thought has been used in order to overcome the difficulties of traditional structure-centred approaches. Lucy used these revised methods of the structure-centred approach to compare number markings patterns in American English and Yucatec Maya (Lucy, 1997). English has obligatory plural grammar system for a large group of lexical nouns; comparatively Yucatec speakers’ plural markers are highly optional (Lucy, 1997). Based on these typological patterns, Lucy conducted a non-verbal experiment requiring speakers to remember and sort types of objects. These experimental tasks yielded the same patterns in the respective languages (Lucy, 1997). In nonverbal tasks involving classifying objects in groups of three, English speakers showed a propensity toward shape-based classifications, while Yucatec speakers showed a propensity toward material-based classifications (Lucy, 1997). These results directly correspond with the lexical structures of the two languages: English numerals frequently modify nouns (e.g. one chair) and Yucatec speakers use of classifiers reveals that nouns of the language “are semantically unspecified as to essential unit”(“e.g. un-tz.íit kib : one long thin wax (i.e. one candle)”) (Lucy, 1997). These experimental tasks illustrate the power a language has over how an individual conceives of categories.

The New Wave in Linguistic Determinism and Linguistic Relativism

In Maya Hickmann’s book review Rethinking Linguistic Relativity she accounts and critiques the arguments of the book that are both for and against the theory of linguistic relativity.

In the first chapter, Slobin explains that the issue of linguistic determinism is reflected in how a speaker chooses and organizes language in discourse “thinking for speaking” (Hickmann, 2000). What this means is that an individual’s own experiences get filtered through the structure of his or her language in which he or she convert into verbalized events. Slobin proposes from a developmental view ‘‘[that] in acquiring a native language, the child learns particular ways of thinking for speaking’’ (Gumperz & Levinson, 1996, p. 76), “providing empirical support for this proposal through narratives produced by children and adults in an identical experimental situation (using a picture book without text) across several languages” (Hickmann, 2000). Different types of linguistic structures of the speakers yielded different types of discourse at early ages, depending on temporal or spatial properties of pictures (Hickmann, 2000). Despite the different language or word choices that adults and children may have, on the whole, adults and children produced certain types of discourses depending on the type of illustration.

Part four of the book discusses linguistic relativity in correlation with social context: a facet often neglected in historical research methods. This part of the book discusses Ochs’ “Linguistic resources for socializing humanity” which suggests three universals that motivate “how language practices encode information about culture and society during socialization”:

- “indexicality principle”: the individual constructs definitions as the interaction unfolds;

- ‘‘universal culture principle’’: commonalities across languages such as indexing and stance;

- “local culture principle’’: culture is made up of a myriad of situationally specific valences that link time, space, stances, acts, activities, and identities’’ (Gumperz & Levinson, 1996, p. 428) (Hickmann, 2000).

These principles highlight commonalities across languages, despite linguistic differences, in indexicallity, all of which might be expressed and sometimes perceived in different ways are foregrounded in socialization.

Conclusion

Language can be interpreted as a powerful manipulator of one’s own cognition. Without language we would be unable to perceive the world in the rich and diverse ways that we do. That being said, although it does seem evident that language shapes our worlds, it cannot be the only factor at play in shaping our thoughts. Just as in other areas of academia, an integrated theory, such as one that includes social context, better accounts for the wide variety of phenomena that may be exhibited. I have only begun to touch on the wealth of information and research involved in the hypothesis of linguistic relativism. I, being limited by the constraints of this web presentation, have not been able to completely discuss the topics in full detail and therefore impress upon you to follow up with the resources provided below.

References

Hickman, Maya. (2000). Linguistic relativity and linguistic determinism. Linguistics, 38 (2), 409-426.

Gumperz, J. J. & Levinson, S. C. (Eds.). (1996). Rethinking linguistic relativity. (Studies in the social and cultural foundations of language). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnstone, Barbra. (2008). Discourse analysis (2nd ed). Carlton, Victoria: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

LEZakel. (2011, February 24). Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis in Interpersonal Communication. Retrieved March 1, 2012 fromhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GRMNrEo7CRw

Lucy, John A. (1997) Linguistic relativity. Annual review of anthropology, 26 , 291-312.

North, Ryan. (2005). Qwantz. Retrieved from http://www.qwantz.com/index.php?comic=627

Further Reading

Ranjit Chatterjee. (1985) Reading Whorf through Wittgenstein: A solution to the linguistic relativity problem. Lingua, 6 (1), 37-63.

Hickman, Maya. (2000). Linguistic relativity and linguistic determinism. Linguistics,

38 (2), 409-426.

Gumperz, J. J. & Levinson, S. C. (Eds.). (1996). Rethinking linguistic relativity. (Studies in the social and cultural foundations of language). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnstone, Barbra. (2008). Discourse analysis (2nd ed). Carlton, Victoria: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Lucy, John A. (1997) Linguistic Relativity. Annual review of anthropology, 26, 291-312.

Lucy, John. A. (1992). Language diversity and thought: A reformulation of the linguistic relativity hypothesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wertsch, James V. (1987). In Social and functional approaches to language and thought. Maya Hickmann (Ed.). Vygotsky and whorf: a comparative analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.