God, the Father

Father Theodore Raines sat in the first row of pews in the Church of the Good Shepherd, staring up at the unadorned gold-plated crucifix above the altar. For more than twenty years he had unselfishly served as pastor at Good Shepherd, conducting Sunday and holiday services and officiating at weddings, baptisms and funerals. Father Raines was always a devoted father to his flock. Year in and year out, he tended to his parishioners' spiritual needs with unwavering faith and dedication. But, much to his dismay, the day finally arrived when he went to the church not to give guidance but to pray for help. For the first time in his life, Father Theodore Raines was experiencing a crisis of faith.

Earlier that week the small, tight-knit community of Essex Springs, Massachusetts, faced a horror that was becoming all too familiar in our society when young Kevin Nesmith brought a semiautomatic rifle to school and opened fire in the cafeteria, killing six students and injuring twenty-two others before turning the gun on himself. As one would imagine, the residents of Essex Springs were in shock. Kevin was the last person one would have expected to become a crazed killer. He had been a Boy Scout, an honor student and the first baseman on the middle school baseball team. He had never gotten into trouble either at school or at home.

Father Raines knew the Nesmith family personally. They, like the families of Kevin's victims, were members of his church. Both the boy's parents were active in church affairs. The minister could only imagine how much they were all suffering. What troubled Father Raines most was that on the following afternoon, a memorial service was to be held for the six slain students at the Church of the Good Shepherd, and he, as the congregation's spiritual father, was to officiate.

Throughout his ministry, Theodore had to perform hundreds of funerals. Furthermore, the deceased parishioners, sadly, were not always adults. There had been eleven-year-old Bobby Kingsley who died of leukemia, several teenagers who were killed in automobile accidents and even one sixteen-year-old girl who had committed suicide back in eighty-three. For the most part, however, the dearly departed were usually upper middle-aged or elderly people whose deaths, though sad, did not have the devastating impact that the death of a young person has.

Now the clergyman was faced with the senseless and brutal murder of six adolescents. Nothing Father Raines experienced, either in the seminary or in his years as a minister, had ever prepared him to face this slaughter of innocence by one of its own. It was a crime that left him demoralized and unsure of his own faith.

The minister had been so intent on his troubling thoughts and doubts that he failed to notice a bent, elderly man enter the church and take a seat in a nearby pew. The stranger watched silently as the minister struggled with his inner demons. Then he saw Father Raines lift a shaking hand to wipe a tear from his cheek.

"It's a terrible thing to bear, isn't it, Father?" the old man asked.

Father Raines turned around, startled.

"I'm sorry," he apologized. "I didn't know anyone else was here."

The minister started to get up, but the old man laid a hand on his shoulder.

"Sit down, Father," he said, slipping into the pew beside him. "Such a tragedy. One can't help wondering ...."

The minister nodded his head in agreement.

"I don't know how I can go through with it tomorrow."

He referred, of course, to the memorial service the following day, and the old man had no difficulty realizing this.

"The families and friends will need your strength more than ever."

"Strength?" the minister echoed. "I don't know if I have that strength."

Father Raines did not wonder why he was revealing his innermost feelings to a stranger. There was just something about the old man that invited confidence.

"Tomorrow afternoon every man, woman and child who walks through those doors will have one question on his or her mind and lips: why? What can I tell them? That it is not up to us as mere mortals to understand God's master plan? How can I face the parents of those murdered children and tell them that it was God's will that their sons and daughters were slaughtered?"

"And what makes you think their deaths were God's will?"

"Because all things serve the will of God," the father replied automatically as though answering a question in Sunday school.

The old man nodded heavily.

"You know," he said, appearing to change the subject, "I often like to stroll around town or sit on one of the benches in the mall and listen to what people are saying."

"And what are they saying now?" the minister asked.

"What people usually say when a child goes bad. They blame the Nesmiths, claiming they must have been bad parents. Some people accuse them of spoiling the boy, while others say they didn't give him enough love and attention. There is also some speculation as to whether there might have been something wrong in the household. They talk in whispers about the possibility of child abuse and inappropriate sexual behavior."

"How can people even think such things?" the minister asked. "The Nesmiths are decent, God-fearing people."

"Perhaps God isn't the one they need to fear," the old man said cryptically.

"I don't follow you," Father Raines said.

"Do you think the Nesmiths are to blame for their son's actions?"

"No!"

"Then what made the boy do such an abominable thing?"

"I don't know. He couldn't have been in his right mind."

"True. But the causes of mental illnesses and emotional problems are often traced back to the parents, are they not?"

The minister found himself beginning to lose patience with the old man.

"You seem quite intent on pinning the blame on the Nesmiths. I can tell you one thing. They are shattered by what has happened."

"Still, someone or something turned an innocent young boy into a murderer, and I don't believe it was God."

"Maybe it was the work of the devil," the minister suggested.

The old man laughed humorlessly.

"I'm sorry, Father. I don't mean to be rude, but I find it amusing that people still blame their shortcomings on Satan. I thought that practice went out with the Puritans."

"Okay, so if it's not God, the devil or the Nesmiths, what do you think caused that poor boy to kill his schoolmates and then himself?"

"Free will," the old man said simply. "For reasons we'll never know and probably wouldn't understand, little Kevin Nesmith chose to take a gun to school, to open fire on his classmates and then to end his own life."

"I don't see how any person can choose to be a killer."

"I think it's hard for most people to understand another's choices, whatever they may be. After all, there are quite a few men out there who would never understand why a man such as yourself would choose to give up more worldly pursuits to spend his life serving God."

"Now, wait a minute," the minister objected defensively.

The old man tried to soothe Father Raines' ruffled feathers.

"Don't get so upset. The point I have been trying to make is that after the worst of any disaster is over and the body count is tallied, people look to each other and to the church for answers. What made the boy do it? How could a child get hold of a gun? Why didn't the school take precautions? People always need someone to blame. And when they come to you tomorrow with these questions, Father, what will you tell them?"

"That it is not up to us to question God's will," Father Raines replied.

"Precisely!"

A disturbing grin broke out on the elderly man's face.

"All other things aside," the stranger continued. "God is the one who gets blamed."

"I didn't say that!"

"Yes, you did. You're telling me that God, the Heavenly Father, sent young Kevin Nesmith into the school cafeteria as part of some cosmic plan for mankind."

"That's not what I meant," Father Raines proclaimed lamely, not sure exactly what he meant by his statement.

"Just as James Nesmith, Kevin's biological father, is not to blame for his son's actions, neither is God, his spiritual father."

"You make an interesting point," the minister conceded, "but this is all just speculation."

"I know what I'm talking about because I am a father," the old man argued. "I want what is best for my children—all of my children. I don't favor one over the other. I stay out of their arguments and disagreements even when I believe one is clearly wrong and the other is right. And like Mr. and Mrs. Nesmith, my heart breaks when my children do wrong. No father wants to see one child kill another, to see one race war against another."

"We are but mortals," the minister said, "we cannot pretend to know God's plan."

"What possible plan could God have that would include an eleven-year-old boy killing other children? To have some crazed cult commit mass suicide? To entice a group of misguided religious fanatics to kill innocent men, women and children in the name of their faith? All these senseless acts of violence are committed by man without the hand of God leading the way."

"You are, of course, entitled to your personal opinion; however, I was taught that God is all-powerful."

"And weren't you also taught that he was all loving and merciful? If such is the case, then how could he ...?"

"... allow such things to happen?" the minister finished the question he'd heard hundreds of times and would probably hear countless more.

"Did you ask the Nesmiths why they allowed their son to do what he did?"

"Of course, not! You have no idea how those poor people are suffering. Not only did they lose a young son, but they are also tormented by guilt over what Kevin did. They blame themselves for their son's crime."

"I know exactly how they feel. I've felt it millions of times over, for thousands of years."

Father Raines stared at the old man. Was he suffering from dementia?

"My only master plan was that you all love one another. Everything else was up to you."

Tears welled up in the man's eyes and gradually spilled over and ran down his cheeks.

"I'm sure the Nesmiths are asking themselves where they went wrong," he continued.

The minister put his arms around the disturbed man, trying to comfort him, fearful he might become violent.

"It's not the Nesmiths' fault, and it's certainly not your fault."

"Do you really mean that?" the old man asked urgently. "Is that what you'll tell the mourners tomorrow when they ask you how such a thing could happen?"

"Yes, if that's what you want me to tell them," the minister said, trying to calm the distraught man.

"I never put men and women on this earth to kill each other."

"I know you didn't."

The old man looked Father Raines straight in the eye. He knew the minister was just humoring him, but he also knew that behind that twenty-first-century skepticism was a man who truly believed in God.

"When I came into the church a few minutes ago, you were having serious doubts."

"How do you know?" the father asked, perplexed. "Was it that obvious?"

"Only to me."

Suddenly, Father Raines heard the heavy church door slam shut. Startled, he turned and looked down the aisle.

"That was odd. I thought the door was closed. Did you leave it ...?"

The minister turned to question him, but the old man was gone.

Once again, Father Theodore Raines sat alone in the first row of pews, staring at the crucifix above the altar. He was no longer having a crisis of faith, however, for he, like Moses, had stood, or rather sat, in the presence of God.

* * *

The following afternoon when the grief-stricken citizens of Essex Springs filed into the Church of the Good Shepherd, their minister stood at the altar ready to spread God's word. His ministry would serve as a beacon, shining light and understanding into the darkness of ignorance.

A hush fell over the sobbing crowd as into the church walked James and Elizabeth Nesmith. Some of those seated in the pews cried even harder seeing the murderous child's parents. Others turned accusing eyes on the stricken couple's faces.

Father Raines walked up to the Nesmiths and embraced them. When he did, he heard a low mumbling of disapproval spread through the assembly. The minister then took his place at the lectern and faced the mourners.

"I know what brought you all here today," he began. "You all came to remember the fallen children. You came to seek what psychologists call 'closure.' You came to shed tears and begin the healing process. But most importantly, you came to ask why. Why. That's a question ministers, priests, rabbis and gurus have been asked for centuries. It's a question that usually doesn't have an answer.

"I'm not going to stand here in front of the Tyndalls, Dormans, Justisons, Carlsons, Petersons, Gillilands and Nesmiths, and the parents of the twenty-two injured children and tell you that I know why this tragedy occurred. I refuse to give you the textbook answer: that this was God's will. God is our father," the minister passionately declared, his tear-filled eyes looking up toward heaven. "And as our father, he only wants what is best for us. But I ask the parents in this room: do our children always listen to us even when we have their best interests at heart? And did we as children listen to everything our parents told us? No. We all have minds of our own, and we act according to our own will, not to some divine agenda of the Almighty."

The people looked at one another uncertainly. This was not what they had expected to hear. They wanted to be told that God had their best interests at heart, and although they will never be able to comprehend his will, everything would work out in the end.

"Let us rise and join hands," Father Raines said unexpectedly. "Seven young children are dead because of a senseless act of violence."

The Nesmiths lowered their heads in shame, as they felt the unrelenting eyes of their neighbors upon them.

"Let us not ask why, for it is a question to which there is no answer. Nor should we point the finger of blame at innocent people. It is not James' and Elizabeth's fault. It is not the school's fault. But most importantly, it is not God's fault. Rather than seek to know why and ferret out a scapegoat, let us simply grieve for those who are gone. Let us help heal those who have been hurt. Let us feel compassion for the families and friends of all seven victims."

Elizabeth Nesmith broke down in her husband's arms.

"Let us not hide behind the old catchphrase: 'It is not up to us to understand God's will.' Rather, we must understand that it is up to us to understand God's will. And what is it that God wants?"

Father Raines' voice softened.

"Only for us to love one another," he added. "Nothing more."

A silence fell over the crowded church, and after several moments of hesitation, the Ryersons hugged the Carlsons, the Gillilands embraced the Petersons, the Dormans cried on the shoulders of the Justisons, and then finally all twelve grieving parents took the Nesmiths into their arms, sharing the common bonds of loss and grief.

Father Theodore Raines looked down from the pulpit at his parishioners, his neighbors, his friends and his own wife and children. The minister felt compassion when he saw the upturned faces of the grieving parents, and he knew that also seated in the pews, invisible to those around him, was an old man who shared the grief of the congregation; for Kevin Nesmith and his six victims were ultimately God's children, too.

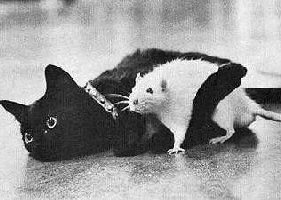

Salem took the theme of this story to heart: the world would be a better place if everyone could learn to love one another. (I'm not sure the mouse was too eager to be hugged by a cat though.)