A Game of Numbers

When Doug Shoemaker was a young boy, he had one passion: baseball. From the first day he played third base for a local Little League team, he fell in love with the feel of a rawhide ball, the scent of a new leather glove and the sound of a wooden bat making contact with a fastball.

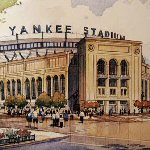

Born and raised in Pequannock, New Jersey, the birthplace of superstar shortstop Derek Jeter, it was no wonder Doug became a diehard Yankee fan. Many a time when he was a boy, he and his father crossed the George Washington Bridge and made the trek to the Bronx to catch a game at Yankee Stadium.

While Doug "Doc" Shoemaker was no Derek Jeter, he was a fairly talented infielder with a batting average consistently above .300. Naturally, his cherished dream was to someday sign with a major league team—hopefully, the New York Yankees. But he loved baseball so much that he would welcome the interest of any team, even—God forbid!—the Boston Red Sox.

Unfortunately, Doug's dream of a major league career was shattered when, at the age of fourteen, he crashed his ATV into a tree. The vehicle overturned, and the teenager's legs were crushed beneath its heavy weight. During his long periods of convalescence and rehabilitation, he sat in his bed with little to do but watch television, read comic books and mourn his lost future in the majors.

In an attempt to cheer their unhappy son, Doug's parents bought him a Dell laptop even though the only prior exposure he had to computers outside the classroom had been as a small child when he played a lemonade stand game on his mother's old Apple II. With his forced inactivity, Doug soon developed an interest in programming. Yet despite an awakening affinity for the cyber world, the young man's first love was still baseball; and although he had little hope of ever being a player himself, he still followed the Yankees religiously.

In his final two years of high school, unable to participate in varsity sports, Doug devoted all his energy to his studies. The former jock surprised both his parents and teachers by graduating at the top of his class. His grades, coupled with high SAT scores, paved the way for his acceptance to MIT. Doug secretly suspected that his being confined to a wheelchair at the time he applied had swayed the admissions officer in his favor—not that he minded. A lot of applicants would have welcomed an injury for a chance to attend the country's most prestigious technical school.

While he was at college, Doug sought to improve his physical condition as well as his mental one. When he wasn't in a lecture hall or the computer lab, he was in the gym. Being in a manually operated wheelchair had built up his arm muscles, and with the help of a physical therapist, he was able to build up his legs.

During his studies at MIT, the young man from New Jersey honed his computer skills. In his final year, he developed a program that could compile baseball statistics of every conceivable type. Within seconds after a user inputs a query, the "Johnny Jeter" program—named after two of Doug's favorite Yankees, Johnny Damon and Derek Jeter—could determine how many right-handed batters had gotten a home run on the second pitch in the bottom of the ninth inning at Fenway Park during a Saturday afternoon game. While this particular obscure statistic might seem too trivial to be of use, it is but one example of the infinite pieces of information Johnny Jeter could produce at a moment's notice.

Word of the program soon spread to the Red Sox organization. Deke Cottrell, former Boston outfielder and one of NESN's broadcasters, after seeing it in action, was interested in knowing if Doug offered a subscription service. Such a program, the broadcaster felt, could be of great value to the team's announcers (even if it had been developed by a Yankee fan). Other clubs in both the American and National Leagues soon showed similar interest. Thus, what began as a class project eventually turned into a multimillion-dollar business.

* * *

Completing the Johnny Jeter program and debugging it were not difficult tasks for an MIT man. On the contrary, not long after graduation, Doug had the test site up and running smoothly. The problem he faced—one equivalent to a weary pitcher facing Mark Teixeira in the batter's box with A-Rod on deck, bases loaded and no outs—was finding an expedient yet inexpensive method of inputting a virtual mountain of data.

"I've got more than a hundred years' worth of baseball statistics to include in my program, not to mention all the games being played now and in the future. We've got thirty teams and a 162-game season; that's a total of 2,430 games in one year, not counting post-season."

Furthermore, he didn't merely want the condensed statistics found in newspaper box scores. For his program to deliver all that he promised, Doug needed complete, detailed, pitch-by-pitch records. He was lucky in that he had the cooperation of all the Major League Baseball teams as well as the Baseball Hall of Fame Museum in Cooperstown, which also wanted to subscribe to the Johnny Jeter online service. Yet even with this vast information at his disposal, the programmer was still faced with the monumental effort of typing the information into a database. With so much work to be done, Doug feared his nascent company would flounder before it ever had the chance to float.

"I can't afford to hire all the people I need to complete the job. Why, the employee health insurance premiums alone cost more than my start-up investment."

It was a lowly business graduate of UMass who gave the MIT grad some sage advice.

"Start small. You don't need a fancy office staffed by full-time employees. Run the company out of your apartment and find a group of people who are willing to work on an as-needed, hourly or piece-rate basis. They, in turn, can work from their homes on their own computers. That way, you'll have minimal overhead. And if you hire them as independent contractors, they're responsible for paying their own taxes."

Doug followed the young man's advice. With a dedicated team of students, housewives and retirees, he was able, in a surprisingly short period of time, to record the history of baseball in bits and bytes on a collection of hard drives. Once the past was neatly filed away, Doug concentrated on the present and future games. He hired his fastest and most accurate data entry people to work for him on a permanent, full-time basis to continually update the database.

By the time spring training came to an end and opening day celebrations were scheduled at ballparks across North America, Johnny Jeter was online and ready to go.

* * *

Doug attended the opening day game at Yankee Stadium. The Bronx Bombers were playing their archrivals and his first customer, the Boston Red Sox. The first pitch was thrown out by the widow of former Yankee shortstop and longtime announcer, Phil Rizzuto. Seeing a picture of the Hall of Famer on the scoreboard brought back memories of Doug's childhood. He fondly remembered his father telling him about the days he had sat in front of his parents' old Zenith console television, watching the games on WPIX.

"I can still hear the Scooter's 'Holy cow!' whenever there's a great play in the field or a long ball hit into the stands," the elder Mr. Shoemaker often reminisced.

It suddenly occurred to Doug as he sat in his own Legends Suite—a perk he got from the Yankee organization for naming his program after two of their players—that since his senior year at MIT, when he first began development of Johnny Jeter, he had thought of little except programming and baseball statistics, yet he hadn't once taken the time to go to the ballpark. Now here he was in the new Yankee Stadium, feeling like Kevin Costner watching the ghost of Shoeless Joe Jackson play baseball in a cornfield in Iowa. For three hours and fourteen minutes, Doug forgot about his ever-expanding business interests and just enjoyed the game. In that brief period, baseball became more than a collection of numbers.

During the seventh-inning stretch, Doug glanced over to the next box where he spied a gorgeous brunette with a dazzling smile and the greatest legs he had ever seen. Once Ronan Tynan completed his moving rendition of "God Bless America," Doug leaned over and introduced himself. The young woman, it turned out, was the sister of one of the Yankees' relief pitchers, a young man who had only recently been called up from the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Triple-A affiliate team.

"This is the first time I've ever been to New York City," the young woman exclaimed with a pronounced Midwestern accent.

"And how do you like it so far, Miss ...?"

"Whitfield, but you can call me Mary Lou. I think this place is great. We don't have fancy ballparks like this back home in Nebraska."

Mary Lou Whitfield took a good look at the young man in the Legends Suite and liked what she saw. She admired the strong, muscular physique, the curly black hair that framed his face with soft ringlets, the hazel eyes that appeared green one moment and brown the next, the pronounced dimples in his cheeks and the slight cleft in his chin. She soon learned that not only did Doug Shoemaker have movie star looks and an athlete's body, but he also had an MIT education and a seven-digit annual income.

The two young people talked for the remainder of the game, which ended in a 7-3 victory for the Yankees. Afterward, Doug took Mary Lou and her brother out to dinner. The rest, as the old saying goes, is history. Mary Lou Whitfield never went back to Nebraska. Not long after the Yankees clinched the division title in late September, she became Mrs. Douglas Shoemaker.

* * *

In less than a decade, the Johnny Jeter program became an indispensable part of every baseball broadcasting booth. One day an announcer for the Seattle Mariners was wondering how many times Babe Ruth swung on the first pitch and got a home run. His partner responded with the line, "Let's ask Johnny Jeter." It was to become as popular a phrase with baseball fans as "If you build it, he will come." Soon "Let's ask Johnny Jeter" began appearing on tee shirts, bumper stickers and baseball caps. When Nintendo licensed the name Johnny Jeter for its newest baseball-themed Wii game, Doug formed a separate division in his company to deal with merchandising.

Soon the boy from Pequannock, New Jersey, and the girl from Silver Creek, Nebraska, were able to afford a high-rise apartment on Central Park West as well as a beach house in the Hamptons. Yet for all his great wealth, Doug didn't really enjoy his life. Since becoming a successful businessman, nearly every waking hour was spent trying to diversify his holdings and boost his profits.

On one of his increasingly rare evenings away from the office, he decided to take his wife out to dinner. After the maître d' seated them, Doug ordered a bottle of Dom Pérignon.

"What's the occasion?" Mary Lou asked, hoping her husband's behavior was motivated by a sudden resurgence of romantic interest.

"I'm about to close a deal with Disney," he replied, nearly bursting with self-satisfaction.

"What have you got to do with Disney?"

"They want the movie rights to Johnny Jeter."

"Why would they want movie rights to a computer program?"

"Not the program. They want to create a baseball-playing character. Remember Toy Story? Well, Pixar wants to make a full-length feature with Woody, Buzz Lightyear and Johnny Jeter. It's the deal of a lifetime. Not only will I be paid a fortune for the movie rights, but I'll also get a percentage of all merchandizing including DVD sales."

Mary Lou didn't share her husband's excitement about the offer from Disney. She was too disappointed that he had taken her out to dinner simply to celebrate a business deal.

"Once the contracts are signed and sealed," he said cajolingly, "you and I can have a second honeymoon, maybe fly to Paris or take one of those Caribbean cruises."

Mary Lou's spirits rose dramatically.

"Can we go to Greece instead? I've always wanted to see Greece."

"Greece it is, then. And maybe Rome, too, while we're at it."

As Doug was signaling the waiter to order a second bottle of champagne, he heard the familiar "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" ringtone of his cell phone.

"Excuse me, darling," he apologized to his wife before answering the call.

"We've got trouble."

Doug didn't need to read the name of the caller on the screen; he recognized the voice at once. It was Enrique Martinez, the young computer genius who oversaw the network from which customers accessed the Johnny Jeter program.

"What's wrong?" Doug asked.

"We're offline. Ballparks around the country are calling in."

"When can you have the network up and running again?"

"I don't know. That's why I'm calling you. I can't find the problem."

"I'll be right there."

Doug gave his wife a sheepish look and signaled for the waiter to bring him the check.

* * *

Enrique and his boss worked long into the night, desperately trying to avert a crisis.

"It has got to be a hardware problem," Doug stubbornly insisted. "There's nothing wrong with the program."

"It's not the hardware either," Enrique argued. "I've run every diagnostic check there is, and they all come up clean."

"Run them again."

"I could run them another hundred times, and I'll still get the same results. The hardware is working properly."

Doug lost his patience.

"No, it's not. Look, I don't care if you have to call Michael Dell himself," he screamed. "I want this hardware fixed before the start of the next major league game."

When the first rays of dawn came through the office windows, Doug was alone, still sitting at Johnny Jeter's main terminal. He and Enrique Martinez had painstakingly run through the complete series of diagnostics a second time, but still, they could find no problem with the hardware.

Doug typed in a simple question to see if the program responded from the main terminal: "What was Lou Gehrig's lifetime batting average?" The program accurately responded, ".340."

Doug asked another half a dozen statistical questions and got the correct answer every time. Then he asked a question that didn't have a numeric answer: "What player holds the record for the greatest number of RBIs?" Just as it had done on the previous evening, the answer came back, "Johnny Jeter."

Doug was perplexed. How could the program answer incorrectly? He typed in a second non-numeric question: "What player led the American League in home runs in 1928?" The answer again was "Johnny Jeter."

The program itself had no bugs, but perhaps someone had hacked into the system and altered the database. Turning the air blue with a stream of curses that would have gotten him ejected from any major league ballpark, Doug exited the query mode and typed in his personal password to enter the database. Once inside, he searched for "Johnny Jeter." Surprisingly, the result was negative.

"That's impossible!" he cried with frustration. "How can the program reply to a query with an answer that's not even in the database?"

The monitor flickered, momentarily flashing a blue screen. Then the data file closed and Doug was brought back to the query mode. He typed in another question: "What player holds the record for the greatest number of career home runs?" The screen turned black, and a DOS prompt appeared on the screen: C:\GREATEST_BASEBALL_PLAYER_OF_ALL_ TIME.EXE.

Doug's right hand momentarily hovered over the keyboard, uncertain of what would happen if he chose to execute the program.

"What the hell? It's not as though my whole future is riding on the success of this program," he said facetiously.

He held his breath as he extended his index finger and pressed the ENTER key.

* * *

It was opening day at Yankee Stadium. More than seventy thousand fans crowded outside the ballpark, hoping to get into the stadium to see the Yankees play the Boston Red Sox. Inside the park, a player in pinstripes walked into the empty Yankee dugout. He was young, barely twenty-two, with the strong, muscular body of a professional athlete. His curly black hair framed his face with soft ringlets, and his hazel eyes appeared green one moment and brown the next. He had pronounced dimples in his cheeks and a slight cleft in his chin.

As the young rookie stared out at the baseball diamond, a group of seasoned ballplayers walked into the dugout, including Waite Hoyt, Joe Dugan, Wally Pipp, Bob Meusel and Babe Ruth.

"Hey kid," the Bambino called when he saw the young man sitting on the bench, "are you the new shortstop Huggins told us about?"

The dark-haired young man stood and offered his hand to the Yankees' Sultan of Swat.

"Yes, I am, Mr. Ruth."

"You got a name?"

The young man smiled and replied, "Johnny. Johnny Jeter."

While it was a household name in the twenty-first century, it was unknown in April 1923. But it wouldn't remain unknown for long. Doug Shoemaker's well-maintained physique and natural athletic ability, coupled with the Johnny Jeter program's vast knowledge of more than a hundred years of baseball history, had given birth to a man who would rewrite the records he had stored in his memory and go on to become the greatest baseball player of all time.

This story is in loving memory of my father, the world's greatest Yankee fan. Incidentally, although the Old Wife is from Salem, Massachusetts, her creator grew up in Pequannock, New Jersey, the birthplace of Derek Jeter.

Salem is a lot like the New York Yankees: you either love him or you hate him. (Despite everything, I love him.)