The Orphan

Sophia Wingate was only eight years old when her parents died, and she had to leave her childhood home in Boston to live with a great-aunt in Sturbridge. Sadly, the young orphan found her new life a lonely one. Not only were her doting parents gone, but also her great-aunt was an old woman who suffered from several chronic ailments and thus had little time for the child.

Things might not have been so bad had Sophia been able to make friends with the local children, but the little girl had been taught by her proud mother to believe that people from Boston were a cut above those from the small towns. Her parents and their Beacon Hill neighbors had been well-bred, cultured intellectuals. Sturbridge—in the Wingates' opinion—was populated predominantly with semi-illiterate farmers, craftsmen and shopkeepers.

Of all Sophia's contemporaries, only one person was not put off by her haughty airs and condescending attitude. The son of the local physician, Lucas Garfield worked as a delivery boy for the town pharmacist and, as such, was the one to take the great-aunt's medicine to her house. It was a task he relished since Sophia always answered the door and conducted the purchase on her great-aunt's behalf. To the small-town boy, the Boston-bred beauty was like a goddess come down to earth from Mount Olympus, a muse to inspire mere mortal men, a young woman to be worshipped from afar.

Shortly after Sophia turned seventeen, her great-aunt finally succumbed to one of the multitude of maladies that had afflicted her. The loss did not adversely affect her great-niece emotionally since the two women never had the opportunity to become close, but the elderly invalid's death did have a severe impact on the younger woman's financial status. Her great-aunt, Sophia learned when the estate was settled, had spent her life's savings—not to mention the money her great-niece's parents had left for their daughter's care—on doctor's fees, medicines and day-to-day expenses. Without an inheritance, the girl was left destitute.

Word of the orphan's predicament spread rapidly through the small New England village. There was much speculation among the residents as to what would become of Sophia now that her great-aunt was gone. Most of the young women in Sturbridge, who were put off by the girl's arrogance, wanted to see her taken down a notch and be forced to seek employment as a shop girl or a housekeeper. One of the wealthier men in town briefly entertained the possibility of making her his mistress, a prospect the snobbish young woman abhorred.

It was Lucas Garfield—the former drug store delivery boy, now a medical school student—who volunteered to legally and morally devote his life to loving and caring for her. When Sophia readily accepted his proposal of marriage, Lucas could not believe his good fortune.

"It's astonishing! Of all the eligible bachelors in Sturbridge, she picked me!" he exclaimed with amazement.

Naturally, no one had the heart to point out that Lucas, greatly admired for his kind and generous nature, was the only man in the village foolish enough to seek the hand of such a conceited, unfeeling woman.

"Sophia Wingate is a cold one" seemed to be the consensus among his friends, family and neighbors. That she would make Lucas miserable one day few people doubted. Some even went so far as to predict that she would bring him to ruin should he dare marry her.

Yet despite the doomsayers' dire predictions, the marriage got off to a good start. Sophia seemed to be generally fond of her husband, although most people assumed she felt more gratitude than affection. Six months after they were wed, the happy couple learned they were to be parents. At first, Lucas was worried about how his wife would react to the situation. There were women, he knew, who had no desire to either give birth or raise children. Given Sophia's selfish nature, Lucas feared his wife would fall into that category. His concerns were unfounded, however, for Sophia was overjoyed at the prospect of becoming a mother.

"I never had any brothers or sisters," she explained. "And then I lost my parents at a young age and became an orphan. I always hoped I would have children of my own to love and care for. Now I will, and we can be a real family."

* * *

"The baby is not due for another three months," Lucas declared when his wife asked him to bring his old cradle down from the attic and set it up in the nursery.

"I don't care. I want everything ready for little James when he arrives."

Lucas smiled with love as he watched his pretty wife lovingly caress her bulging abdomen as though she could feel the child within her womb.

"James, is it? And how do you know our baby's going to be a boy?" he asked. "You might be carrying a girl."

"While I would certainly love our child no matter what its sex, I just know that this one is a boy. I can feel it."

Sophia's instinct proved to be correct. The child was indeed a boy. Unfortunately, he was born prematurely and died shortly after his birth.

As was to be expected, Lucas was heartbroken. Still, he took comfort in his faith and in the belief that in time he and his wife would conceive another child, one—God willing—Sophia would be able to carry to full term. Although he mourned the loss of his infant son, he was able to look forward to the day when his house would be filled with laughing, happy, healthy children.

But while dreaming of this idyllic future, he failed to take his wife's emotional state into account. Sophia was not merely heartbroken like her husband was, she was utterly devastated. As the weeks and then months passed, she slipped into a deep depression, eventually becoming so despondent that she tried to take her life. When Lucas suggested that they try to have another baby, his grieving wife tearfully confessed that the last thing she wanted was to take the risk of losing another child.

"I couldn't bear to go through it all again," she sobbed. "James was a part of me. My body nourished him; my heart beat for him. When he died, a part of me died, too."

The compassionate young doctor was more concerned with his wife's overwhelming grief than with his personal loss. He loved Sophia more than his own life and would do anything to make her happy. Yet how could he help ease her terrible pain?

"There is something you can do for me," she told him one evening.

"Anything at all. Whatever you want, I'll move heaven and hell to get it for you."

"Take me away from here. This house and this town are constant reminders of all that I've lost."

"All right, darling," he reluctantly conceded, not eager to move away from his home and family. "Where would you like to live? Do you want to return to Boston?"

"No. I was thinking we could go west and start a new life in California."

Lucas was taken aback by her unexpected request. Such a long trip through treacherous territory was extremely dangerous, and only desperate people with nothing to lose attempted it.

"We can travel by train as far as the Mississippi River," Sophia explained. "Then from there, we can purchase a wagon and oxen to take us through the Great Plains."

"Traveling all the way to California by wagon is an arduous journey," Lucas protested.

"I read that thousands of people are making the trip—more and more each day."

"Yes, I know. And it is estimated that one in every ten dies along the way."

"People die right here in Massachusetts," she reminded him. "You asked me what would make me happy. This is it."

Lucas sighed with resignation, knowing he could not refuse her retreaty. If he did, she might lose all faith in him.

"I'll go see my father tomorrow. I'm sure he'll lend us some money for the journey."

* * *

Given his wife's Boston manners and refined sensibilities, it amazed Lucas to see how well she adapted to pioneer life—much better than he did, in fact. He supposed that far from the confines of New England society, Sophia was free to be herself. Although the journey proved to be every bit as hard as Lucas had envisioned, it did not dampen her spirits. On the contrary, she seemed happier and more at ease in her homespun dress with her hair loosely pulled back beneath a simple sun bonnet than she had in all her Boston finery.

Lucas, on the other hand, was not holding up well. His muscles ached from hours of driving the uncomfortable prairie schooner over miles of bumpy trail; and his stomach reacted violently to the steady diet of bacon, bread, dried meats and rice, with only an occasional serving of fresh fruit and vegetables. Most of all, he missed the comforts of home that he had previously taken for granted: a warm, comfortable bed; cool, fresh drinking water from the well; his old chair in front of the hearth; and a seemingly endless supply of fresh food. He despised the hot sun, the drenching rains, the bone-chilling winds, the annoying insects and the dangerous wild animals on the prairie. Yet he stoically endured these discomforts in silence because he loved his wife.

From time to time, the Garfields joined other wagons along the Oregon Trail and enjoyed the company of their fellow settlers. Just as often they passed freshly dug graves, painful reminders to Lucas that he and his wife might not make it all the way to California. But even though they traveled through the shadow of death, Sophia did not show fear. Her husband wondered if perhaps the reason she remained so calm was that she did not care whether she lived or died.

Maybe this journey, he thought, is nothing more than another, slower attempt at killing herself.

* * *

The pioneers had just passed Chimney Rock, a well-known landmark on the trail, when they saw in the distance three wagons stopped beside a small stream.

"It's odd that someone would be at camp in the middle of the day," Lucas noted with misgiving.

When he saw the vultures circling the air above the wagons, his suspicions were confirmed. He pulled on the reins to steer the oxen clear of the camp.

"Where are you going?" Sophia demanded to know. "They may need our help."

"See those buzzards up there? Those people are beyond our help."

"You don't know that," she argued. "There may be survivors."

Lucas did not want to stop. Whatever danger had struck the people in those wagons could pose a serious threat to them as well. His wife, however, insisted that they offer their assistance if needed. Once again, against his better judgment, Lucas acceded to his wife's wishes.

As they drew nearer to the wagons, the putrid stench of death and decay became overpowering. Sophia put a handkerchief to her nose, and Lucas nearly vomited up his bacon and dried meat lunch. Although the odor of the dead bodies was appalling, the sight of the first victim was far worse. Sophia let out a startled cry and turned her head from the gruesome sight.

"What do you think happened to her?" she asked her husband, carefully keeping her eyes averted.

Lucas looked at the corpse, or rather what was left of it after the vultures and wild animals had fed on it. The body showed signs of dehydration, which, coupled with the sunken eyes, led him to believe the cause of death had been cholera.

"Stay in the wagon," he warned his wife.

"Is there anyone left alive?"

"I doubt it. If there were, surely someone would have buried this unfortunate woman, but I'll look and see."

Lucas walked toward the wagons, checking inside each one. There were nine more bodies, male and female, all in much the same state as the dead woman they had first encountered.

"Well?" his wife asked when he returned to his own wagon.

Lucas shook his head.

"They're all dead."

Anxious to put distance between them and the possible threat of cholera, he climbed up into the driver's seat, took the reins in his hands and nudged his team back toward the trail.

A sudden movement caught Sophia's eye.

"There's something there by the last wagon."

"Probably a wolf or a coyote," Lucas suggested; but upon closer examination, he was stunned to see a young boy, five or six years old, apparently alive and well.

Sophia jumped down from the wagon, ran to the child and took him in her arms.

"You poor thing," she cooed, hugging him to her breast. "You're an orphan, just like I am."

"Let me make sure he's all right," her husband declared.

He examined the boy closely. The child was pale and underweight, but although there was a good deal of blood on his shirt, he appeared well and completely unharmed.

"You take him to the wagon," Lucas instructed his wife. "I'll see if I can find any clue as to the identity of his parents."

"Why? What does it matter now?"

"We'll have to find the next of kin and tell him or her that the boy is safe."

Sophia, fearful that the relatives might claim the child, vetoed the idea.

"His parents are dead. Our son is dead. I believe it was God's will that we found him here and that we raise him ourselves."

Sophia's eyes glistened with tears and hope. Lucas knew it would break her heart to give up the boy.

"Who am I to argue with God?" he asked, touching the child lightly on his head.

Not long after the couple resumed their journey, the boy fell asleep on Sophia's lap.

"I think I'll call him James," she said, smiling wistfully. "After all, that's what I would have named our son had he lived."

Lucas looked down at the sleeping child. The fair hair falling gently over the closed eyes was a vision of pure innocence, yet he found something faintly disturbing there, too.

* * *

During the next several weeks, Lucas kept an eye on James. Thankfully, the boy exhibited no symptoms of serious illness. On the contrary, he seemed to be thriving on Sophia's loving care. There was definitely more meat on his bones and a robust, rosy color in his cheeks. Unfortunately, the same could not be said of Sophia, who looked on the verge of collapse.

"I'm fine," she assured her worried husband. "I'm just tired; that's all."

"Maybe taking care of the boy is too much for you. Are you sure it wouldn't be better to find his family?"

Sophia's eyes flashed with anger.

"James is mine! Do you hear me? Mine! I won't allow you or anyone else to take him from me."

Lucas tried to soothe her, but she pulled away from him and joined the child in the back of the wagon.

"Maybe she does just need some rest," he told himself optimistically, but he could not ignore the doubt that plagued him.

The following day when Sophia woke after a long night's sleep, she looked no better. Her eyes were lifeless and her face ashen.

"We're stopping at the next fort," Lucas vowed. "You need medicine."

"I told you I'm fine."

"You are not!"

A moment later the sickly woman proved her husband correct by fainting in his arms. When Lucas opened the top buttons of her blouse to give her fresh air, he gasped with horror. Beneath her homespun dress were bloodied bandages, which he gingerly removed to examine the wounds beneath.

"Good God!" he lamented when he saw the small teeth marks in his wife's flesh.

He immediately grasped their meaning. While James had been at the camp with ten dead adults and no one to care for him, he had apparently sunk to the level of the wild animals around him. Of necessity, he had become a scavenger. And once he had developed a taste for human flesh, he became a predator.

As one would destroy a rabid dog, Lucas was determined to slay the "animal" that was slowly cannibalizing his wife's body. He went to the back of the wagon where James was sitting, and the boy made no attempt to escape. It was as if the child had no fear of the man. His mind trying to banish the deep-rooted conviction that murder was an unforgivable sin, Lucas placed his hands on the child's neck and began to squeeze.

"God forgive me!" he prayed.

A sudden, loud crack rent the air. Sophia had regained her senses and stood near the opening of the wagon with her husband's smoking shotgun in her hand. Lucas lay on the side of the wagon where the deadly blast had thrown him. He fought for breath, trying to speak despite the agonizing pain in his chest.

"Why?" he managed to ask.

"I can't let you hurt my son," Sophia replied, feeling neither regret for her deed nor sympathy for her dying husband.

Resigned to his imminent demise, Lucas closed his eyes, and his head fell back. But even before the young man's heart beat for the final time, James leaned over him and began to feed.

* * *

A small group of Mormon converts was traveling from Illinois by wagon train to Utah along the Oregon Trail. As the pioneers neared Fort Bridger, a fur-trading outpost located in what is now the state of Wyoming, where the trail forked north toward Oregon or south toward California and Nevada, the driver of the lead wagon spied a lone prairie schooner sitting motionless beside the trail.

"It looks like they might be in trouble," he told his wife who was sitting beside him. "We will stop and see if we can be of any help."

Inside the covered wagon, sitting contentedly between the decomposing corpses of Sophia and Lucas Garfield, little James smiled with joy. He had seen the train of Conestoga wagons approaching, and he was hungry again.

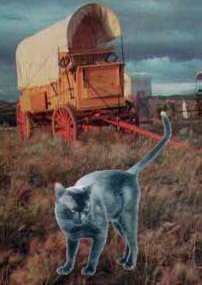

I've heard of a prairie dog but never of a prairie cat.