At the Crossroads

Curtis Blackmore rarely saw his mother when he was a boy. A live-in servant of a rich white family in the French Quarter, Mrs. Blackmore saw her son only on Thursdays, her day off. From the time the boy was in diapers, it was his maternal grandmother who raised him.

As a substitute parent, Grandma Marie was loving but strict. She taught her grandson to be honest, hardworking and respectful, but it was the lessons she inadvertently taught him that had the greatest impact on his life.

Although a devout church-going Christian woman, Grandma Marie put her grandson to sleep at night with tales of the voodoo queen Marie Laveau and the powerful loa, spiritual intermediaries between man and his creator. Of all the stories she told him, Curtis found the fable of the devil at the crossroads the most fascinating.

"Does the devil really have the power to grant you your heart's desire?" the young boy asked, wide-eyed with wonder.

"Chil', it be not the devil, the one they speak of in the Bible. It be a devil."

"But can it grant wishes?"

"That's what they say. The trouble is you can't always trust a loa. There be good spirits like Dhamballah Wedo, but there also be evil spirits like Marinette."

"So the spirit at the crossroads is evil?"

"It might be, if it exists at all. Who knows? I ain't never seen it."

After hearing his grandmother's bedtime stories, Curtis felt a sense of awe whenever he approached an intersection of two roads. Was there a devil nearby, he wondered every time he stood at a crossroads. Surely there were none in the crowded, paved streets of New Orleans where there were streetlights all year round and where brightly clad celebrants congregated during Mardi Gras.

But there were other, less travelled roads: roads that ended in swamps and roads where there were neither lights nor houses. The child could easily imagine a devil appearing there in the moonlight to offer unsuspecting humans wealth or success in exchange for their souls.

Eventually, however, Curtis lost his childish belief in his grandmother's somewhat macabre bedtime stories. There was a Great War raging in Europe, and with so many able-bodied men off fighting for their country, the teenager was able to get a job in the kitchen of a grand hotel on Canal Street. The work was hard and the hours were long, but even the meager pay was a help to his mother, whose health was beginning to fail.

Although he was forced to step into a man's shoes before his time, Curtis's life was not entirely bleak. On Saturday nights, when his shift in the kitchen was over, the young man would walk along Bourbon Street with coworker and friend, Clyde Shirley, and listen to the music that flowed out of the jazz clubs.

"I likes a good Scott Joplin rag myself," Clyde declared when Curtis praised a Jelly Roll Morton tune one evening.

As the two young men turned and headed back toward Canal Street, they passed a grizzled old man who was sitting on a doorstep playing a guitar. Curtis stopped and listened, mesmerized by the music the man created. It was not the toe-tapping beat of jazz or ragtime or the praise-the-lord hallelujah-ing of gospel music. Rather, the sound was melancholic and intensified the listener's feeling of loneliness.

"Come on," his friend urged. "It's getting late, and I gotta get home."

"You go ahead, Clyde. I wanna hear this man's music," Curtis replied, inching closer to the old guitar player.

"You like dis song?" the musician asked with a deep, raspy voice.

"Yeah. What is it?"

"It don't have a name. It just be called da blues."

"The blues," Curtis echoed, thinking it was an appropriate description of the poignant melody.

"Only t'ing I play is da blues."

As the young man watched, fascinated, the musician's agile fingers danced over the strings of the guitar.

"Can you play?" the old man asked.

Curtis shrugged his shoulders.

"Don't know. I ain't never tried."

The musician stopped playing and handed over his guitar.

"Go ahead."

The old man was a patient teacher, but it was clear that Curtis was no musician. The guitar that had emitted such sonorous notes for the blues man produced only discordant noise in the teenager's hands.

"I can't play!" he cried with frustration and handed the instrument back to its owner. "I have no talent."

"God gives each and every one of his children a talent," the old man declared, and then added with a good-natured chuckle, "but I s'pose guitar playin' ain't da one he gave you."

* * *

The music the grizzled old man referred to as "da blues" haunted the teenager from that night on. He just couldn't get it out of his head—not that he really wanted to.

His mother's health had been deteriorating rapidly, until finally, after years of faithful service, the poor woman was released by her employer and sent home to die. For the next several months, Curtis not only had to financially support himself, his mother and his grandmother, but he also had to help his frail, elderly grandparent take care of his dying mother. When the end finally came, he felt relief rather than loss. He knew he should grieve, but he couldn't. Maybe it was because his mother was a virtual stranger to him. Still, he was a dutiful son and made regular visits to her grave.

It was while he was walking home from the cemetery one dark, drizzling night that he heard the mournful sound of a blues guitar being carried to him on the wind. Like the fabled children of Hamlin, he followed the melody, unaware that it would lead him to a crossroads.

Through the darkness, Curtis could see the shadow of a man sitting atop a split rail fence.

"You know the blues?" he asked the mysterious man with the guitar.

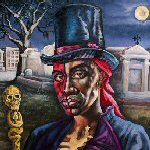

The top-hatted stranger laughed.

"Yeah, I knows da blues. Here," he said, offering Curtis the guitar, "play somet'ing for me, somet'ing sweet and sad."

"I can't play a note," the young man admitted, refusing the man's request.

But when the stranger thrust the instrument at him, he took it in his hands. As though the guitar were electrified, a tingling shock raced up Curtis's arm.

"Now you go ahead and play," the stranger commanded.

At first Curtis gingerly plucked the strings, but as the tingling in his arm subsided, his skill increased. After only a few songs, he could play as well as, if not better than, the grizzled old man he and Clyde had met on Bourbon Street. With an effort, the young man stopped playing and reluctantly handed the guitar back to the stranger.

"You want dis guitar?" the man asked.

Curtis laughed humorlessly.

"Hell, I won't ever be able to afford a guitar, 'specially one as nice as that one. I have to keep the roof over my grandma's head and put food on the table."

"Who said anyt'ing about money?"

All of a sudden the drizzling rain stopped, the clouds parted and the two men at the crossroads were bathed in moonlight. For the first time, Curtis realized the stranger was no mortal man but a loa.

"I s'pose it's my soul you want in exchange for this guitar."

"What would I do with your soul? If you want dis musical instrument here, you has to pay me with t'ings I like."

"And what's that?"

"Rum, tobacco and women," the spirit replied with a smile.

"Women?"

"Pictures will do."

"So you're sayin' if I give you rum, tobacco and pictures of women, you'll give me that guitar?"

"I give you da guitar right now, and every year on dis night, you come back to dese crossroads with my rum, tobacco and pictures."

"Every year? And what happens if I stop coming here?"

"Then dat fine guitar will be useless to you because you won't be able to play a note."

Curtis didn't need a lot of time to think the matter over since a man who has nothing to lose doesn't worry too much about being swindled.

* * *

Ten years went by, a decade during which Curtis made ten trips to the crossroads to leave his annual tribute of rum, tobacco and photographs of scantily clad beauties. The loa made good on his promise: Curtis became not only one of the greatest guitar players of his time but also one of the most renowned Delta Blues musicians.

His rise to fame had been a lonely journey, however. Within days of meeting the loa at the crossroads, he lost his Grandmother Marie to cancer. He buried her next to his mother and left New Orleans to pursue his music career. For the next few years, Curtis travelled throughout the South, with only his guitar and an occasional bottle of whiskey to keep him company. Until one night when he played a juke joint near Baton Rouge.

"Who is that?" Curtis asked a local piano player, when he saw Coretta carrying drinks to a group of railroad workers who were sitting at a table near the makeshift stage.

"You don't wanna go messin' around with her," the piano player warned. "Her daddy owns dis place, and he don't cotton to us musicians flirtin' with his little gal."

Curtis had no desire to dally with the beautiful waitress, however. His intentions were strictly honorable, so he showed up at Coretta's house Sunday after meeting and asked her father for permission to court his daughter. The juke joint owner was clearly impressed by the young man's good manners and eased up on his rule forbidding Coretta from socializing with musicians.

The couple dated for only six months before Curtis proposed marriage. Because of the amount of time the musician was on the road, their engagement lasted longer than most. Finally, at age twenty-eight, the blues guitar player wed the beautiful twenty-year-old waitress.

The two honeymooned in New Orleans, and while they were there, the groom showed his bride the sights from his childhood. They also made a brief visit to the cemetery where Curtis's mother and grandmother were buried.

While they were returning from the graveyard, they drove past the crossroads, and the musician was reminded of his deal with the loa. The anniversary of their meeting was quickly approaching, and he would have to pay the annual tribute soon. When that day came, he had to give an excuse to his bride for leaving her.

"I have to go see my uncle," he lied.

"You told me everyone in your family was dead," Coretta protested.

"I didn't tell you about my uncle because he was in jail, and I was afraid if I told you about him, you might think I was like him."

Coretta put her hands on her husband's face and gently kissed his lips.

"I would never think bad of you."

"I'll be home as soon as I can. I promise."

An hour later, Curtis pulled his car to the side of the deserted road, got out and stood in the center of the intersection. From a paper bag, he took out a bottle of rum and a can of tobacco and placed them on the ground. Then he reached into his jacket pocket for the photographs.

"Dat not what I want."

Curtis's pulse quickened. Although he had heard that eerie voice only once before, he remembered it clearly.

"We had a deal. I was to give you rum, tobacco and pictures of women in exchange for the guitar and the skill to play it."

The loa materialized. He was dressed like a poor field hand except for the worn dress coat and black top hat. Around his neck he wore a string of tiny bones. Curtis stifled a laugh. He had never expected his benefactor to look like a caricature of Baron Samedi.

"I grow tired of looking at pictures. I want a real woman."

"And what am I s'pose to do, go to Storyville and hire a hootchie-cootchie woman to come out here and visit you?"

"A living, breathing woman would be of no use to me; I'm a spirit, damn it!"

Curtis felt his stomach lurch. His grandmother had told him tales of voodoo worshippers sacrificing chickens to the spirits, but he had never heard of sacrificing humans.

"You can forget about me bringin' you a dead body. You'll just have to make do with the pictures like we agreed."

"I tol' you I want a real woman, like dat fine young t'ing you be married to."

"No way!" the musician said, shaking his head from side to side.

"Lessen you want to forget how to play da guitar, you'd better deliver Coretta here to me by midnight tomorrow."

"Go to hell," Curtis shouted before returning to his car and driving away.

* * *

When he returned from his honeymoon in New York City, Curtis Blackmore picked up his guitar and started to play—or at least he tried to play. Why couldn't he remember the chords? Why did his fingers fumble as he tried to find the right frets? The loa had threatened to take his talent away, but he didn't believe him. He had played the guitar flawlessly for so many years that he assumed it had become second nature to him.

"What's that you're playing?" Coretta asked, wrinkling her nose with distaste.

"Nothin'," he replied. "I was just seein' if the guitar needed tunin'."

"From the sound of it, I'd say yes," his wife laughed.

How was he going to play in front of an audience? He would be booed off the stage for the no-talent phony he actually was. But other people learned to play, why couldn't he?

For the next six months he turned down all job offers, regardless of the amount of money being offered, telling everyone he wanted to spend time with his new wife. During those months, however, he snuck off by himself and tried to regain some of his former mastery of the guitar. Sadly, he made no progress.

Coretta, who was expecting a child by that time, failed to notice her husband's despondency. All she could think about was the impending blessed event.

Finally, Curtis had to admit that he would never learn to play on his own. Without the help of the loa, his music career would be over.

The following morning, he woke early, left a note for Coretta on the kitchen table and returned to New Orleans.

* * *

Curtis stood at the crossroads in the moonlight, waiting for the loa to appear.

Finally, he called out into the darkness, "Where are you?"

There was no reply.

He had been standing in the middle of the intersection for more than an hour when he finally decided his visit was pointless. Then as he reached for the door handle of his Ford Model A, he heard the voice behind him.

"You come to strike another bargain?" the loa asked.

"I'll give you anything you ask—anything except my wife."

"Your pretty wife be with chil'."

"Yes."

"I t'ink it be a girl chil', and she will be as fine-looking as her mother."

"You want my baby? But it won't be born for several months yet."

"It don't matter to me. Like I tol' you last time we met, I'm a spirit. I got lots of time to wait. You swear to give me da baby when it comes, and I'll give you back your talent tonight."

With a heavy heart, Curtis nodded his head.

* * *

When his performance came to an end, Curtis hurried off stage and telephoned his mother-in-law to ask about his wife.

"The baby gonna be here soon," the woman told him. "You better get here as fast as you can."

He got into his car and sped to his in-laws' home where his wife lay on the bed, in labor.

"Is everything all right?" he asked the neighbor who had experience as a midwife.

"No problem so far."

Exactly eighteen minutes later, the old woman declared that she could see the top of the baby's head.

"It's coming."

Curtis sat in the living room with his father-in-law, preferring to let the women oversee the birth. As he waited for news of the delivery, the expectant father drank a glass of whiskey and silently prayed to his grandmother's all-powerful, all-merciful god that the child would be a boy.

He held his breath as he heard his wife's scream of pain, followed moments later by the wail of a newborn baby.

"It's a girl!" his mother-in-law cried, running into the room to make the announcement.

The child was healthy and beautiful, and it broke Curtis's heart that he would have to kill it. What choice did he have, however?

"Have another whiskey, Daddy," his father-in-law offered jovially.

Curtis eagerly accepted. He downed it quickly and then had not one but four more drinks. Bolstered by alcohol and a great love of his music, he crept to the wooden cradle in the middle of the night and suffocated his infant daughter with a down pillow.

* * *

Coretta was heartbroken by the death of her child. The tiny body was placed in a small coffin, and the parents drove it down to New Orleans to be buried near Curtis's mother and grandmother.

One night, after dinner, while the couple was still in the Big Easy, Curtis lovingly took his wife's hand.

"We're both young and healthy," he said gently. "We can have other children."

The grieving mother turned her head away.

"Why don't you play something for me?"

As her husband picked a song on his guitar, Coretta poured him a glass of whiskey. He swallowed it down and followed it with a second and a third.

Suddenly, she rose from her chair and put on her shawl.

"I want to go to the cemetery."

"Now? It must be close to midnight."

"Please! I want to visit her grave. I need to visit it."

"All right," he said, humoring her.

A mile from the crossroads, Curtis began to feel an ache in his stomach, a pain that intensified the closer he got to the intersection. He was able to drive another three-quarters of a mile before he was forced to pull the Ford off the road. He stumbled and then crawled the rest of the way. Behind him, his wife followed silently.

There was no need to summon the loa that night; the spirit was standing at the crossroads waiting for them. With the cramps gripping his stomach, Curtis could barely stand.

"We had a deal," he told the loa.

"Yes, and I kept the bargain I made with you. I gave you back your musical ability, didn't I? But now I got to keep my deal with your pretty wife."

Slowly dying from the poison Coretta had put in his whiskey, the musician barely summoned enough strength to turn toward her and ask, "Why?"

"You killed my child," the grieving mother replied with unconcealed hatred.

Once Curtis was dead, his widow stepped over his body and took the loa's hand.

"Come, my sweet," the spirit said to her. "We will journey to my realm, where you, me and da baby can be happy together for da rest of time."

This story was inspired by the legend of Robert Johnson, the great blues musician who some people say made a deal with the devil at the crossroads.

Honest, Salem! I don't know how that cat voodoo doll got in my drawer!