Darkness in the City of Light

For filmmaker Nate Radnor, the silver screen was tarnished. After fulfilling his childhood dream of making horror movies and becoming as renowned in that genre as Roger Corman and Wes Craven, the fire of ambition that had burned in him when he first arrived in Hollywood was extinguished. The motion picture industry made him a very wealthy man, but it did not give him a lasting sense of accomplishment.

As a child growing up in New Jersey, he loved to watch the old black-and-white thrillers on Chiller Theater and Creature Features. He enjoyed not only the classic monsters such as Frankenstein, Dracula and the Wolf Man but also the lesser known cast of characters: Godzilla, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, the Mummy and the Thing. While other kids his age were playing sports or listening to rock 'n' roll music, Nate was writing his own short stories about vampires, zombies, werewolves and mutant species intent on killing humans. Thanks to financial assistance from his parents, he was able to move to the West Coast after graduating college and pursue a career in writing, directing and eventually producing his own films.

Maybe it's time for me to go back east, he thought after signing the divorce papers his third wife's lawyer had FedExed to his home. There's nothing to keep me here now. God knows I don't have to work. I've got more money than I'll ever be able to spend.

The prospect of leaving the movie capital excited him, but he was only fifty-five and still in good health. He could reasonably expect to live another twenty years or so. What would he do with himself if he quit making films? He suddenly remembered the short stories he wrote as a child.

Could I tackle something as ambitious as a novel?

The idea appealed to him, and the more he considered it, the more tempting it became.

And even if it doesn't get published, who cares? The joy for me has always been in doing the work, not in taking credit for the finished product.

Nate kept busy the next six months, untangling himself from all the invisible ropes that bound him to Hollywood. After agreeing to a more-than-generous divorce settlement, he was a single man again. He sold his production company to a rich kid right out of UCLA film school and his house to a New York soap opera star who wanted to make the transition to feature films.

"So, you're going back to Jersey?" his former secretary asked as he took the last of his personal belongings out of what was once his office.

"Yeah. A local realtor has arranged for me to see a house in Morris County this weekend—that's where I grew up."

Yet before he had the opportunity to view the five-bedroom colonial located near the Ford Mansion, which served as George Washington's headquarters during the winter of 1779-80, Nate changed his plans. On the plane from LAX to Newark Airport, he watched the 1943 version of The Phantom of the Opera in which Claude Rains starred as the disfigured musician who haunted the Paris Opera House.

Nate had never been to Paris. In fact, in his fifty-five years, he had never left the United States, not even to visit its neighbors, Canada and Mexico. He knew from his literature classes in college that Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Oscar Wilde once resided in la Ville Lumière, the City of Lights. It had long been a city that inspired writers, poets and artists of all kinds.

With the same hopeful enthusiasm that had taken him to California more than thirty years earlier, he promptly decided to move not to New Jersey but to Paris, France.

* * *

For the first time in his life, Nate Radnor was able to do whatever he wanted, and he basked in the heady feeling that freedom gave him. Taking along only his laptop and what he could carry in a single suitcase, he left both his native country and the world of movie-making behind him and crossed the Atlantic Ocean, looking forward to the opportunities that awaited him as a novelist and expatriate.

I'll stay on in Paris until I finish my first book, and then I'll move to London and write a second one. And who knows where I'll go from there? Switzerland? Fiji? Timbuktu? In another ten or fifteen years, I may have nothing but a pile of unpublished manuscripts, but at least I'll have traveled the world.

Since he had no intention of putting down permanent roots, he leased a furnished apartment with an excellent view of both the Seine and the Eiffel Tower. Once he was moved in—a process which involved little more than unpacking his suitcase and going to the nearest store to buy a few grocery staples and personal hygiene items—he hired a guide fluent in English to show him the highlights of the city. For nearly two weeks, Etienne Girard, a handsome young man who earned a modest income conducting private tours of the city, gave the American a crash course in French history as they visited places such as the Louvre, the Panthéon, the tomb of Napoleon Bonaparte at Les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, La Conciergerie and the Place de la Concorde.

"So, this is where King Louis and Marie Antoinette lost their heads?" Nate asked, as the two men stood in the famous square near the three-thousand-year-old Luxor Obelisk, given to the French by the Egyptian government in 1833.

"Yes. This square was originally called Place Louis XV, but in 1789 it was renamed Place de la Révolution, for obvious reasons. The revolutionaries tore down the statue of Louis XV, and put up a guillotine. In addition to the king and queen, there were other notable people executed here: the convicted murderess Charlotte Corday, Madame du Barry, Georges Danton, Camille Desmoulins and Maximilien Robespierre."

"It's funny," Nate said, as the two men returned to the car to head toward their next destination, Notre-Dame Cathedral, which was nearly destroyed by a devastating fire in April 2019.

"What's funny?"

"I found fame and fortune in horror, and here I am in France, and what do I see? A mummy at the Louvre, skeletons in the catacombs and the site where thousands of people were beheaded by a guillotine. And don't forget all the graves we've visited—from the French kings and queens buried at the Basilica St. Denis and the tombs of France's honored dead at the Panthéon, to the burial sites of Oscar Wilde and Jim Morrison at Père Lachaise Cemetery."

"I see your point," Etienne laughed. "I suppose you have been seeing the darker side of the City of Lights. I'll tell you what. Let's put off seeing Notre-Dame for now. Frankly, it's depressing to see it in the condition it's in. I'll take you to Montmartre instead. You can see where some of the world's greatest artists used to congregate, not to mention the famous red windmill of the Moulin Rouge."

The two men had lunch at Le Chat Noir, a modern café named after the nineteenth century cabaret; toured the surrounding district; and then, having had enough of dodging tourists with French-English dictionaries, street maps and selfie sticks, Nate decided to call it day. On the drive back to the filmmaker's apartment, Etienne took a short detour and drove down Rue Chaptal.

"Are you going the right way?" the American asked.

"While we're in the Quartier Pigalle, there's one more sight I want to show you."

"Not another grave, I hope," the passenger laughed.

"Not exactly, but since you are a master in the world of horror, it should be a must-see on your list of places to visit in Paris."

When Etienne turned his car onto a narrow, dead-end street, Nate became apprehensive. He had found his guide's name on a flyer posted near his apartment and had not bothered to check his references. What if the personable young Frenchman was a criminal who planned on robbing him and leaving him for dead in some Paris alley? For a man who had always paid for taxis rather than put his trust in an Uber driver, it was a foolish action.

"See that building at the end of the cul-de-sac?" Etienne asked.

"You mean the one that appears to be abandoned?"

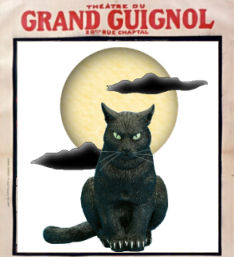

"That was once Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol."

The name meant nothing to Nate, a fact that surprised his guide.

"You've never heard of it? From the time it was opened in 1897, it was known for its controversial productions. They were often meant as social commentaries and featured the less desirable elements of Parisian society such as prostitutes, criminals and the poor. When a new owner took the theater over, he turned it into a house of horrors. The plays performed here were famous for their graphic, gruesome scenes."

"I assume from its appearance that the theater closed down?"

"Back in 1962. After the war, attendance steadily dropped. It seemed no play at the Grand Guignol could match the real-life horrors of Hitler and the Nazis."

"And the building has stood empty for more than fifty years?"

"No. There have been other theaters here since then including one for the hearing impaired."

"Thanks for showing me this place," Nate said. "I just might use it in my novel."

Rather than go out again, the filmmaker made himself a salad for dinner. While he was eating it at the small table in his apartment, he opened his laptop and searched the Internet for information on the Grand Guignol.

Seeing a play there must have been like watching an old "B" movie.

Memories of sitting in front of his parents' television with a bowl of Jiffy Pop popcorn and watching The Blob, House of Wax, Carnival of Souls and Castle of Blood came back to him.

Ah! Those were the days! he thought nostalgically. If only I could turn back ....

Nate's eyes suddenly widened, and the fork in his hand stopped on its journey from the salad plate to his open mouth.

I may not be able to turn back the hands of time, but I can resurrect a small part of the past.

Just as Le Chat Noir recreated some of the charm of its nineteenth-century namesake, he could revamp the old theater and bring back the Grand Guignol. It would take time—probably a good deal longer than it would take him to pen a novel—and it would no doubt be expensive. But what the hell? He had plenty of money to spend and nothing better to do with his time.

This will be a lot more fun that writing a book that more than likely will never appear in print.

* * *

When Etienne found a parking space near the apartment building, expecting to have to wait for Nate to come down, he was surprised to see the American waiting for him by the curb.

"You're early," the driver needlessly pointed out. "You must be eager to see the Palace of Versailles."

"Not today," Nate announced as he climbed into the passenger seat of the Citroën. "I've got something else in mind. But first, let me ask you. How would you like a full-time job?"

"How much sightseeing do you expect to do while in France?"

The filmmaker briefly outlined his plans to purchase the old theater and bring the Grand Guignol back to life.

"Since I don't speak a word of French, I'll need you to be my righthand man."

Etienne imagined his job would be little more than that of a glorified interpreter and gofer, but when Nate talked salary, he could not refuse the offer. Once he was on the American's payroll, the young Frenchman spent close to a year researching the original features of the theater and working with the architect and construction crew to replicate its neogothic design and recapture its eerie atmosphere.

While his assistant was seeing to the restoration of the building, Nate concentrated on what productions would be put on in the new Grand Guignol. To appeal to as many people as possible, he would offer a combination of authentic plays and new, performed in both French and English.

"On Saturday and Sunday evenings, the plays will be presented in French, and the Friday evening and Saturday matinee performances will feature English speaking actors," he told Etienne as the two men stood on the cul-de-sac, inspecting the exterior of the theater.

"What's the first play you plan to put into production?" his assistant asked.

"I haven't decided yet. I have seven decades of plays to choose from. Unlike Broadway theaters where they sometimes show the same one for months or even years, the Grand Guignol had a quick turnover, often more than two dozen different shows in a single year. Unfortunately for me, many of the scripts I've found haven't been translated into English."

Eventually, he chose Le Laboratoire des Hallucinations, written by André de Lorde, a play about a surgeon who performs radical brain surgery on his wife's lover, thus causing him to have hallucinations.

Opening night of the newly renovated theater proved to be a great success. All the research, planning and hard work paid off. To generations raised on movie franchises featuring Michael Myers, Freddy Krueger, Jason Voorhees and Jigsaw and television series about zombies and vampires, the introduction to live theater was a fresh medium to view the familiar genre. Word of the ghoulish entertainment being offered by the American film producer spread through Paris, and soon every show was sold out.

His own genius and hard work aside, Nate owed much of the success of the project to Etienne Girard. Without him, he most likely would never have learned about the history of Grand Guignol. The young Frenchman was so much more than an interpreter and gofer; he literally ran the day-to-day operations of the theater while the owner kept busy dealing with the actors and directing the performances. It was no surprise then when Nate appointed his former travel guide as manager of the theater.

Once Le Laboratoire entered the fourth week of its run, Nate turned his thoughts to future productions. He was ready to cast the second play, L'Horrible Passion, also written by André de Lorde, which told the tale of a nanny who strangles the children in her care. But in addition to the Grand Guignol classics, he also wanted to include at least two or three new plays a year. Thus, he put the word out through the theater grapevine that he was looking for a playwright.

Aimeé Marchand walked into the theater the following week, when he was auditioning a number of actresses, all hoping to be cast in the role of the murderous nanny. Nate's eyes were immediately drawn to her, as she was the most attractive woman in the room. She was not a glamor girl like the Hollywood actresses he was familiar with. Hers was a classier look: regal, cultured and refined.

Definitely not a nanny type, he decided. A queen or a countess, yes, but not a nanny.

"Let's start with you," he said, pointing to a middle-aged woman who looked like a servant right out of Downton Abbey.

"Excuse me," Aimeé said after the woman was done reading her lines. "Can I speak to you a moment?"

"I'm afraid you'll have to wait your turn. These other women were here before you."

"But I'm not an actress; I'm not here to audition."

"Just a moment, ladies," Nate told the others and took Aimeé aside.

"Can I help you with something?" he asked.

"I'm here to help you."

"How?"

"You wanted a playwright, didn't you?"

"And you know one?"

"I am one," she said as she reached into her oversized handbag and took out a script.

"Darkness," Nate said after glancing at the first page. "A good title."

"It's about a young girl, one of the filles du roi, the so-called 'daughters of the King,' who were sent to New France in the seventeenth century to marry the French settlers there."

"I'm sure your play is very entertaining, but the Grand Guignol is not the appropriate venue for love stories."

"This isn't a romance, Monsieur Radnor. It's a horror story involving multiple murders."

"All right. Why don't you leave your script here, and I'll take a look at it?"

"Thank you. My name and number are on the last page."

When Ms. Marchand left the theater, Nate returned to auditioning the actresses. But as he listened to the women recite their lines, the director could not stop thinking about the captivating playwright.

* * *

Having chosen a young and inexperienced, but talented, actress for the role of the psychopathic nanny, Nate left work for the day. After purchasing the old theater, he had taken up permanent residence in the city and frequently stopped at a nearby café to unwind after a busy day. He sat at his favorite table with a bottle of wine and began reading Aimeé Marchand's script. Before finishing his first glass, he was swept up by the story it told.

Yvette Beaulieu was born in Bordeaux, the youngest of ten children in a poor family. When her parents and siblings died of the plague, the two-year-old child was sent to a convent in Paris that cared for helpless orphans. Under the supervision of the nuns, she grew to be a genteel, educated young woman. Her intentions were to take her vows and live out her days with the sisters, but fate had its own plans for her.

In 1667, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French Finance Minister for Louis XIV, contacted the convent, asking for volunteers among the orphans to travel to New France to be wives of the settlers. Seeing it as her patriotic duty, Yvette became one of the King's Daughters, the filles du roi. After being given a trousseau and a dowry of fifty livres, she boarded a ship for the New World.

The pretty French orphan, still in her teens, found life in New France unbearable. The winters were long and extremely cold, and the colonists lived in constant fear of an attack by the natives. To make matters worse, her husband drank; and when he had imbibed too much, he became belligerent and abusive. For more than a decade, she endured verbal, mental and physical abuse. Then, after a beating which led to her fourth miscarriage, the desperate wife murdered her husband and fled her home.

For several years, she wandered through the wilderness, forced to feed on whatever animals she could find in order to survive. During the coldest months, she found shelter with the Algonquin and Iroquois, but come spring, she resumed her solitary trek, always heading south. Eventually, she made it as far as the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but she found no peace there. The Puritans were frightened by her wild appearance, believing she was no better than the savages who threatened their existence. And when they learned that she was a Catholic as well, they banished her from their community.

From New England, she journeyed further south to New York where she found a second husband, who was little better than her first. Although a drunken bully, he had one thing her first spouse lacked: money. The poor orphan girl who had previously led such a hard life was at last able to live in relative comfort. Unfortunately, it was at this point in her life that she fell in love—and not with the man to whom she was married.

Despite having been brought up in a convent with the intention of becoming a nun herself, Yvette had no qualms when it came to sinning.

Religion is for the privileged or the weak, she decided not long after arriving in North America. The strong who hope to survive the hardships of this untamed world cannot rely on God for help. I'll not die on my knees with my hands clasped in prayer. I will stand and fight instead.

Therefore, the concept of guilt did not deter her when she entered into an adulterous affair with the son of a French Huguenot who fled the religious persecution in France to live among the Dutch in what had once been New Amsterdam. Nor did it prevent her from brutally murdering her second husband when he discovered her infidelity and threatened her with divorce. Fearing for her own life, the two-time killer took as much of her husband's money as she could carry with her and sailed back to France with the intent of living out the rest of her days in obscurity in Bordeaux.

Nate drank the last of his bottle of wine and finished the dinner he ordered while reading the script.

"It's not the type of play usually presented at the Grand Guignol," he later told the playwright when he phoned her from his home. "But if you make the husbands' deaths more gruesome and maybe include a scene where the Indians scalp someone .... Or, better yet, you could change the ending and have the heroine escape to New England where she is found guilty of witchcraft and executed."

"If it's gore you want, maybe that play isn't right for you," Aimeé said, with no hint of disappointment in her voice. "I do have another one, though, that might be more to your liking. This one is similar to the first, but it involves vampires, too. Why don't we meet for lunch tomorrow, and I'll show it to you?"

* * *

The second play also went under the working title Darkness.

"I just finished writing the script," Aimeé explained, "and I haven't had the opportunity to think of a good title."

"Since your first play hasn't been produced yet, we can always keep the name for this one."

As the playwright sat quietly opposite him at his favorite table at the café, Nate read her script.

The year was 1728, and Emilia Faucheux was about to set out for New Orleans to marry one of the French colonists there.

"That seems to be a popular theme of yours: French women running off to the New World to marry colonists," Nate remarked.

"I was always told a writer should write about what he or she knows, so I looked to my family history for inspiration."

"One of your female ancestors went to Canada to find a husband?"

"Yes, but obviously she returned to France or else I would be living in Quebec."

Nate poured them both a glass of wine and continued reading the script.

When the ship docked in New Orleans, the passengers walked down the wooden plank, each carrying a small coffin-shaped chest, a cassette, that contained her belongings. The young women, having endured a six-month-long journey over rough seas, appeared thin and excessively pale.

Single men, who were eager to find wives, were at the dock to meet them. They looked at the filles à la cassette (as the potential brides became known) with suspicion. Who were these pale women, they wondered. Were they prostitutes, like the Baleine Brides sent to Bienville seven years earlier? What diseases did they carry that stole the rosy color from their cheeks?

Soon after their arrival, the women were taken to a convent on Chartres Street, to be looked after by the Ursuline nuns. Although a handful of them soon became wives, once word got out that several of the women suffered blistering to their pale complexions when exposed to Louisiana's hot tropical sun, other potential bridegrooms were reluctant to follow suit. With no hope of marriage, some of the women were forced into prostitution, and a few took their own lives. Eventually, the king learned of their plight and demanded they return to France. Emilia, alone, remained behind.

Once the Casket Girls—as their nickname eventually evolved—left New Orleans, strange tales began to circulate. Rumors worsened when a fur trapper was found dead, drained of his blood, along the banks of the Mississippi River. Not long after his body was discovered, all the windows on the third floor of the Chartres Street convent were boarded up with nails said to be blessed by a Catholic priest. The door to that floor was boarded up as well. Whatever was being held captive on the third floor, it was obvious the nuns would take all precautions to see that it did not escape.

Despite the sisters' best efforts, however, Emilia Faucheux, formerly known as Yvette Beaulieu, managed to escape her prison. After murdering her first husband, seeking refuge in the wilds of New France and existing on wild animals, she had developed a taste for blood. Years of this ghoulish diet transformed her into a vampire. To avoid suspicion in Massachusetts and New York, she avoided taking human victims. When she returned to France, however, she occasionally allowed herself to feast from the veins of a peasant.

Eventually, the people of Bordeaux discovered her secret. She was forced to return to the New World, this time to New Orleans—not to find a husband but to seek sanctuary. On the voyage, she existed by sparingly drinking the blood of her fellow Casket Girls; but after her arrival, she was able to feast on nomadic trappers who sometimes came to the city to sell their pelts. Emilia believed she had at last found a safe home in which to settle. As long as no one found the remains of her victims, she could live undetected among the humans.

But then the king demanded the unmarried Casket Girls return to France. Since she was not one of the few who had taken a husband, she was expected to go with them. Knowing what awaited her in her homeland, she disobeyed the nuns and remained in New Orleans.

When the Cajun's bloodless body was found, it was not difficult to figure out what had killed him. The nuns lured the vampire to the convent and locked her on the third floor until they could summon a vampire killer to rid the city of the vile monster. However, if Emilia had learned one thing in her long years, it was how to survive. Using an andiron from the fireplace, she repeatedly struck the wall until she broke through. Once free, she calmly descended the stairs, drained the blood from two nuns and disappeared into the Bayou.

"This play is much more suitable to the Grand Guignol than the previous one you gave me," Nate declared when he came to the end of the last scene.

"Does that mean you'll produce it?" Aimeé asked eagerly.

"Yes."

* * *

By the time Le Laboratoire des Hallucinations closed and L'Horrible Passion opened, Aimeé Marchand, working closely with Nate Radnor, put the finishing touches on her script. Before casting began on Darkness, the playwright became the filmmaker's fourth wife.

On their honeymoon cruise of the Baltic Sea, the bride began writing her third play. Like the previous two, it was never intended to be presented on stage but, instead, was written as the third chapter in her personal memoirs. Its plot centered on a nearly four-hundred-year-old French vampire who marries for the third time. After less than a month of marriage, her husband falls victim to a strange blood disease and dies. The widow then becomes the owner of the Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol.

Along with her handsome, longtime lover, Etienne Girard, her late husband’s theater manager—born the son of a French Huguenot in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam—who had followed his beloved from New York to Bordeaux more than three hundred years earlier and then from Bordeaux to New Orleans and eventually to Paris, Yvette/Emilia/Aimeé makes the theater a true house of horrors. The rumors about patrons dying during or shortly after attending performances or disappearing after entering the theater are considered nothing more than urban legends and only add to the Grand Guignol’s macabre appeal.

The Grand Guignol was an actual theater in Paris, known for its macabre productions. It closed in 1962, but the building in which it was located is not vacant. It is currently the home of the International Visual Theater.

Both the filles du roi and the filles à la cassette were groups of French women who were sent to North America to become the wives of French settlers. The Casket Girls, as the latter group became known, inspired legends of vampires in New Orleans.

Salem once auditioned to appear in a play at the Grand Guignol, but his only acting experience was in an amateur production of Cats.