The Lost Children

Known for the famous hiking trail that extends from Maine to Georgia, the Appalachian Mountains is a region in the eastern United States that is home to many families who earn their living by farming the land. Jonah Ludwell was the third generation to live on the property that his grandfather had cleared when Pennsylvania was still under the thumb of the British king. He lived in a two-story farmhouse, which he built with his own hands, along with his wife, two young sons and an infant daughter.

Five years before the start of the Civil War, there were already rumblings of discontent both in the slave-holding South and the free states of the North. Talk of politics rarely reached the mountain community, however. Small farmers like the Ludwells were too preoccupied with planting and harvesting crops, milking cows and feeding chickens to worry about the wider world around them. Jonah's life revolved around his farm and his family, until one day in April 1856 when his fragile universe came crashing down like a house of cards.

It had been a cold winter, and there was still a light dusting of snow on the frozen ground. The temperature, which hovered at the freezing point at midday, dipped below it once the sun set. With the baby sleeping peacefully in her cradle, Alvina Ludwell sat down to dinner with her husband and two sons.

"This food looks good," Jonah said, always one to express appreciation of his wife's efforts.

He had put in a long, hard day making much-needed repairs to the barn, and all he wanted was a hot meal and a good night's sleep.

The boys—Teddy, age seven, and Jon Jon, age five—were full of energy, as young children often were. They fidgeted in their seats, and their mother cautioned them not to wake their sister.

Halfway through his meal, Jonah heard the family dog barking at the door.

"Go let Willy out," he told his older boy.

Once the door was opened, the animal raced out into the yard and in the direction of the woods that bordered the farm to the north.

"Willy must be chasing something," the boy said when he returned to the table. "He took off as soon as I let him out."

"I hope it's not a skunk!" Alvina declared, remembering how long it took for the smell to fade the last time the dog was sprayed by one.

"If he comes back smelling like skunk, we'll have to shut him up in the cellar. It's too cold to leave him out all night."

Outside, the dog continued to bark at something or someone.

Jonah swallowed the last of his supper and announced, "Let me go see what all the commotion is about."

He then put on his warm jacket and got his shotgun. Although exhausted, he managed a smile.

"Just in case," he told his wife with a wink of his eye.

Alvina began scooping up dirty dishes from off the table and carrying them to the sink. When she returned to the dining room, she noticed the boys were no longer there. Since the house was quiet and still—a rarity with three children—she assumed Teddy and Jon Jon had gone with their father. She saw no cause for alarm. Jonah would risk his own life to protect his sons.

"I do hope it's not a skunk! I can't very well lock the boys in the cellar all night."

By the time the table was cleared, Willy had stopped barking. Alvina was standing over the sink, her hands and lower arms emerged in soapy water, when she heard the front door open. Hearing the dog's footsteps on the hardwood floor, she sniffed the air. There was no smell—thank God!

"Whatever it was must have run off when it heard Willy," Jonah announced.

"Would you see the boys get ready for bed while I finish washing these dishes?"

"Sure thing. Are they upstairs?"

Despite the hot dishwater, Alvina shivered from the chill that swept over her.

"Aren't they with you?"

"No."

Not even bothering to dry her wet, soapy hands, the worried mother was fast on her husband's heels as he took the stairs two at time to the second story of the farmhouse.

"Teddy! Jon Jon!" the father shouted, not caring if his raised voice woke his daughter.

"Come out here," his wife commanded. "This is no time for games. Do you hear me?"

The only reply was the sound of little Sara's cries at her peaceful slumber being disturbed.

"They must have gone out to look for you," Alvina told her husband.

Given the freezing temperature, it was urgent the boys be found as soon as possible.

"Come on, Willy," Jonah called to the dog. "We've got to go look for them."

"I'll get my coat and go with you," his wife offered.

"No. Someone has to stay here and take care of Sara."

Alvina was still rocking back and forth in the old wooden rocking chair, her daughter sleeping peacefully in her arms, when the first rays of the morning sun began lightening the night sky. It had been hours since the boys went missing, and her husband had yet to return.

Where can they be? she wondered, half out of her mind with worry.

Shortly after dawn, she heard a voice calling in the distance.

"Teddy! Jon Jon!"

Her heart seemed to fall like a boulder from her chest to her gut. The boys had not been found!

They were out in the freezing cold all night!

Jonah's faint voice, hoarse from repeatedly yelling his sons' names, grew louder as he neared the house. Finally, the door opened and he stepped inside. He knew from his wife's expression the boys were still not home.

"I'm gonna need help to find them," he announced. "The snow's not deep enough and the ground's too hard for anyone to leave footprints behind."

"Let me go get dressed, and I'll help you. I can bundle Sara up and bring her with me."

"No. This is men's work. I'm going into town to ask for volunteers. What I need you to do is see to the animals while I'm gone. They have to be fed, and the cows need to be milked."

Alvina nodded her head in agreement. Despite the turmoil the parents felt at their sons' disappearance, they could not shirk their responsibilities as farmers.

"Let me just feed Sara and put her down, and then I'll go out to the barn. Do you want me to make you something to eat first?"

"No. I don't have time. I want to get to town as quickly as possible so that I can get back here and continue searching."

Finding two little boys in those tree-covered mountains was not exactly as difficult as finding a needle in a haystack, but it was pretty damn close!

* * *

By the time the sun began to set at the end of the day, nearly a hundred people had joined in the search. Not a one of them found any sign of Teddy and Jon Jon. There were even more volunteers the second day, but the results were the same. A dowser offered his services, but all he could locate with his L-shaped divining rods were a few horseshoes and an Indian arrowhead.

When dawn broke on the third day, most people had little hope of finding the boys alive, but they still stubbornly trudged through those woods, calling their names. Long before psychologists talked of "closure" in relation to death and mourning, they knew the Ludwells would feel a whole lot better if they could give Teddy and Jon Jon a decent burial.

There were those, however, who still held on to the belief that the boys were alive. One of these optimists suggested they ask Aggie Goring for help. Mention of the old woman's name caused an immediate reaction from the volunteers. Many widened their eyes in horror; some shook their heads in stubborn refusal; others smiled in amusement that anyone would take the rumors of Aggie Goring's "powers" seriously. She was no witch, they believed, just an eccentric old hag, bilking gullible people out of hard-earned cash for her silly spells and worthless charms.

However, the Ludwells, desperate to try anything, paid the old woman a visit.

"I know why you've come," Aggie said in a raspy, unpleasant voice. "You want my help in finding your lost young'uns."

This was no indication of prophecy or clairvoyance on her part since word had spread throughout the area of the missing boys.

"We don't have much ...," Jonah began, but the old woman brushed his words aside.

"I don't want your money. I just want to help you find your babies."

Relying on her own form of folk magic, Aggie filled a basin with water and placed it on her kitchen table. Then, taking an egg from her pantry, she cracked the shell and spilled the contents into the water. The alleged witch then stared at the yolk floating on the surface.

"I can see them," she announced.

"Are they ....?"

Alvina could not bring herself to ask the question, fearing that she would receive confirmation that they were dead.

"They're alive, but they're cold, tired and hungry."

"Oh, thank God!" the two parents cried in unison.

"Where are they?" Jonah inquired.

"It looks to me like they're near the old Babson place."

"All this time I just assumed they followed me and Willy into the woods," the father said with surprise. "That's why we haven't found them yet. We're been looking in the opposite direction!"

On Aggie's advice, all the searchers reversed their course and headed south of the Ludwell farm. They went over every square foot of the abandoned Babson property and the surrounding areas but found nothing. The inevitable grumblings of discontent and frustration could be heard amongst the groups of volunteers.

"Why spend days looking in the woods and now completely abandon that area and look here?"

"Old Aggie had a vision in which she saw the boys near here."

"I wouldn't be surprised if that witch had something to do with their disappearance herself. Maybe she killed those boys and ground up their bones to use in her spells."

"Quit talking like a lunatic and keep searching."

"Whose idea was it to ask that crazy old woman for advice anyway?"

"The parents."

"Aren't they the ones who said the boys went into the woods? Seems to me they would at least know which direction they went off in."

"Maybe this has all been nothing more than a wild goose chase."

"How so?"

"Could be the children never wandered off at all."

"Then, where are they?"

"This last winter was a bad one. People have been known to go a little crazy when they're cooped up inside for months at a time."

"You think one of the Ludwells killed the children?"

"I just think it's mighty peculiar that we haven't found hide nor hair of them."

The volunteers were not the only ones to cast suspicious eyes on Aggie Goring and the Ludwells. The local lawmen had doubts of their own. They searched both the witch's cabin and the parents' farm but could find no evidence of any crime having been committed.

Teddy and Jon Jon seemed to have vanished into thin air.

* * *

Meanwhile, as the search continued and volunteers grew more disheartened and suspicious with each passing day, Caleb Hollander, a young farmer whose wife had taken ill with influenza, welcomed his brother-in-law, Enis, who came to pay his sister a visit.

"How's she doing?" Enis asked after his wife, Gladys, went to look after the sick woman's children.

"Much better. The doctor was here yesterday, and he said she ought to be up and about in another couple of days."

"That's great news. What about you? You look a little peaked. Don't tell me you're coming down with it now."

"No, I'm just tired; that's all."

"Taking care of a farm, a sick wife and three young'uns would tire any man out."

"That, and I've been having dreams," Caleb confided in his brother-in-law. "Last week two boys went missing."

"I heard something about that when I stopped in town on the way out here. Did you know them personally?"

"I know their parents, Jonah and Alvina Ludwell. We all go to the same church. Most of the men around here have been out looking for the missing boys, but I couldn't very well leave my sick wife and children to join them."

"Of course not."

"The night they went missing, I had the first dream; and I've had it every night since then."

"The same dream over and over again?"

"Yes. Nothing changes. I'm out in the woods, searching along a riverbank, and I stumble across the carcass of a dead deer. A little ways ahead I see a child's shoe lying on the ground. I keep walking. There's a birch tree down, and I have to climb over it and then down into a deep ravine. That's when I find them."

"Alive?"

Caleb shook his head.

"Their two little bodies are huddled at the base of a giant oak, clinging to each other as though trying to keep warm. I now it's only a dream, but I can't get that picture out of my head!"

"Maybe you've been having these nightmares because you feel guilty about not joining in the search," Enis suggested.

"I suppose that's possible."

"With Gladys here to help look after my sister and the kids, there's no reason you and me can't volunteer to help. If we go out and look for those missing children, you may stop having the dreams."

Caleb and his brother-in-law rose early the following morning, and after seeing to the farm animals, they headed toward the river that ran through the woods to the north of the Ludwell property. By midmorning, the two men, covering ground that had already been searched, found nothing.

"How old are these boys we're looking for?" Enis asked.

"Five and seven."

"You think they could have got this far on foot on a dark night when the temperature was below freezing?"

It was a good question; one the original searchers had asked themselves. The answer those volunteers arrived at was no, so they had turned back and searched closer to the farm. Caleb, however, spurred on by his dreams, would not give up.

"Let's follow the river a little while longer."

It was nearly noon when Enis, lagging well behind his sister's husband, heard his brother-in-law's cry.

"What is it?" he asked, out of breath from having to run to catch up with Caleb.

"Look up ahead. It's a dead deer just like in my dream."

"Well, I'll be damned! The boys did make it this far."

"Don't go jumping to conclusions. Finding the carcass could be a coincidence."

They walked further and came upon a child's shoe.

"That isn't a coincidence," Enis insisted. "What is it you saw next? A deep ravine?"

"No. First comes the fallen ...."

The young farmer fell silent, for blocking the path up ahead was a downed birch tree. Again, just like in the dream. Fearing what he would find on the other side, Caleb stopped in front of the rotting trunk.

"Come on," his brother-in-law urged. "It can't be too much farther."

Teddy and Jon Jon were about the same age as his own children. He did not want to see their lifeless little bodies with their arms clasped around each other in a frozen embrace. Still, he had come this far. He could not turn back now. As he approached the edge of the ravine, he saw the naked branches of an oak tree reaching for the sky.

"That's it," he muttered. "That's the one."

Teddy and Jon Jon Ludwell had been found.

As if discovering the children's bodies was not distressing enough, Caleb was also distraught by his prophetic dreams.

"I can't explain it. Nothing like this has ever happened to me!" he told his brother-in-law since he did not want to upset his wife while she was still recovering from the flu.

"As I see it, there's only one explanation," Enis replied. "You've been blessed with a gift. Maybe you had it all along and it took a tragedy like this to bring it out."

"I suppose so, but I sure hope I've seen the last of it."

* * *

The Ludwells received word of their sons' fate with mixed emotions, the foremost being grief. Guilt ranked high among them as well, especially for the mother, who blamed herself for not watching them more closely.

"It's not your fault," Jonah assured her. "The boys were safe inside the house. How could you know they would go out after me?"

Teddy was seven years old, he thought, he ought to have known better.

Lastly, there was a sense of relief. Not knowing whether the boys were alive or dead had been torture. The thoughts of Teddy and Jon Jon alone in the woods, cold, hungry and frightened could now be put to rest.

Despite the generally held belief that the children had simply gotten lost and died from exposure, suspicion still lingered in the minds of many of the people in the mountain community—suspicion that extended to Caleb Hollander, the man who found them.

"How did he know where they were?" people asked.

"We had more than a hundred men combing those woods and couldn't find anything. And he goes and finds them right off."

"I heard he was led to the spot by a dream."

"Who told you that?"

"Probably the same damn fool who suggested the parents ask Aggie Goring where their boys were."

"Maybe he's a witch, too. Can men be witches?"

"I don't know, but it's possible Old Aggie caused him to have those dreams."

Rumors aside, law enforcement officials concluded the boys' death was accidental.

People will be people, however; and once an idea gets into someone's head, it tends to remain there. For several years, Aggie Goring, previously regarded as little more than a colorful character, became a social pariah. The Ludwells fared little better. Only during Sunday services did their neighbors suffer to remain in their presence. As for Caleb Hollander, he stopped going into town altogether, even to attend church. The whispers and stares he had to endure were worse than the dreams that continued to plague his sleep.

For five long years, the fate of the Ludwell children remained at the forefront of people's minds. Then, on the fifth anniversary of the disappearance, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter, and the country, recently torn in half by secession, was plunged into war. Caleb told no one—not even his brother-in-law—of the dreams he had foretelling the carnage that was to come.

Why bother Enis with my visions of a great battle at Gettysburg and the eventual assassination of the president? he asked himself. If my dreams are right, which they all have been so far, he won't survive the fighting at Bull Run.

Of the hundred plus men who had searched for Teddy and Jon Jon Ludwell, more than half would be killed, and a third of those who survived would be maimed for life. Even Jonah, the father of the dead boys, would fall at Fredericksburg.

Caleb, who was one of the lucky ones to come out of the war unscathed, returned home in the summer of 1865 to an empty house. His wife, who was never a strong woman after recovering from influenza, took sick again and died while he was fighting the Rebels in Virginia. Their three children were sent to live with Gladys, their Uncle Enis's widow.

Despite his heroic deeds during the war, Caleb was still looked upon with lingering suspicion by many of the townspeople. Only Alvina Ludwell, who lived in the shadow of doubt herself, welcomed him home.

"This isn't much of a home anymore," he said, when the two met by accident in the church graveyard.

"I know what you mean. You and I both lost so much."

"How's your little girl?"

"Sara isn't so little anymore. She just turned nine. What about your children?"

"I haven't seen them yet. They're living with their aunt and her new husband in Pittsburgh. I thought about going there and getting them back—since Gladys is only their aunt by marriage, not by blood—but I don't know. At least they've got a good home there. What have I got to offer them?"

"Love."

A simple and obvious answer. And a true one. He did love his children, but rather than uproot them again, he moved to Pittsburgh to be near what remained of his family. From time to time, he received letters from Alvina Ludwell, who despite remarrying still lived on her late husband's farm. When her letters stopped coming—shortly after the nation lost a second president to an assassin's bullet—he did not have to wonder why. He had foreseen both her death and President Garfield's in his dreams.

Long before that time, Caleb ceased questioning his unusual gift and simply accepted it. For forty-five years, he experienced clairvoyant visions not only of major historical events but also of milestones in the lives of the people he knew. He had foreseen the Chicago fire and the marriages of his three children; the Johnstown flood and the births of his grandchildren; the assassination of a third president, William McKinley, and the passing of his sister-in-law, Gladys; the destruction of the USS Maine and the death of his oldest grandson in the resulting Spanish-American War. Except for the details of his first dream, which he had shared with Enis, he never told anyone about his visions.

I learned that lesson the hard way, he thought, remembering the reactions of his neighbors when he found the Ludwell boys' bodies. Besides, I don't want to be remembered as the Nostradamus of Pennsylvania.

* * *

Caleb Hollander's advanced years weighed heavy on him. Both his eyesight and his hearing were failing, and his body suffered from diverse aches and pains. While he had lost many of those he held dear, he still had two children and nine grandchildren. They were the reason he got up every morning.

"That was the best chicken dinner I ever ate!" he complimented his daughter on her cooking one evening.

"I'm glad you liked it, Dad. I hope you saved room for dessert. I made your favorite: apple pie."

"I'll just have a small piece."

After dinner, the family gathered in the parlor, where Caleb's son-in-law picked up a copy of Mark Twain's The Prince and the Pauper and began to read aloud. Although the elderly man enjoyed the tale of Tom Canty and Edward Tudor, he could not help nodding his head and dozing off now and again.

"I'm sorry, I just can't seem to stay awake," he apologized. "I think I'll go on up now and get some sleep."

When he crossed the threshold into his room, the bed looked inviting. The sheets were clean and pressed and the comforter seemed warm and cozy. Moments after his head hit the pillow, he was asleep.

He had not dreamt that dream in nearly fifty years, but every detail of it was still fresh in his mind. He could feel the frosty air of that cold April morning and hear the sound of the rushing river whose banks were nearly overrun by the thaw of the winter snow. It was all the same. But, no, it wasn't.

That's where the dead deer ought to be.

However, the carcass was long gone. Feeling like a young man in his twenties again, he continued walking.

No child's shoe either. I wonder what happened to it.

The birch tree was also gone. Only the giant oak remained. As he approached the edge of the ravine, he was uncertain what he would find there. Despite being in a dream, he knew the difference between past and present. The boys were no longer missing; their bodies were buried in the churchyard next to the graves of their mother and father.

They're still here! Caleb thought with amazement when he saw Teddy and Jon Jon near the base of the oak tree.

But they were not huddled together in death. They were both very much alive.

"We never had the chance to thank you for finding us," Teddy said.

"Thank you," Jon Jon echoed his older brother.

"Come on, boys," Caleb called to them. "Give me your hand, and I'll help you out of that ravine. Then I'll take both of you home. Your parents will be glad to see you. They've been worried sick about you."

It was the last dream the old man would ever have. His daughter would find him dead in his bed the following morning. In the years ahead, she would continue to grieve over her loss but would be comforted by the memory of the peaceful smile she had seen on her father's face when she found him.

Although the characters in this story are fictional, the tale was inspired by the true account of the April 1856 disappearance of Joseph and George Cox, ages 7 and 5, sons of Samuel and Susannah Cox who lived in the Allegheny Mountains (part of the Appalachian chain). A douser and a witch were called in to assist in the search, but it was Jacob Dibert (accompanied by his brother-in-law) who found the children after having several dreams that revealed the boys' location to him.

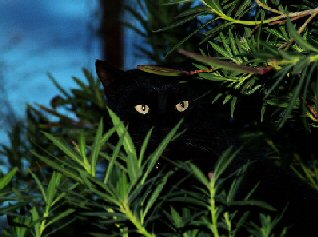

Salem was once lost in the woods. Unfortunately, he found his way back home!