The Radio

As the owner of the Days Gone By antique shop, Madge Strickland frequently attended rummage sales, flea markets, public auctions and estate sales in search of hard-to-find treasures as well as reasonably priced collectibles to sell in her Gloucester Street store. Many times she found it necessary to take along her widowed father, a man well into his eighties, who like many elderly people sometimes experienced an occasional loss of memory.

One Saturday afternoon in early October, Melvin Hardy accompanied his daughter to such an estate sale in Newburyport. A renowned, sixty-seven-year-old politician, a former Republican state senator, had died suddenly in his sleep, and the entire contents of his summer home were being auctioned off by his grieving spouse and children. Madge had already previewed the items that were to be put up for bid and made a list of the items she wanted to purchase—provided the prices did not go above what she was willing to pay for them.

During the first hour of the auction, she successfully bid on a gilt bronze bouillotte lamp, a Chippendale camelback sofa and a Seth Thomas mantel clock that needed some tender loving care, but she let a rare Hepplewhite highboy and a pristine Sheraton desk go to a higher bidder.

Madge was eagerly waiting for the auctioneer to bring out a Gorham 1865 silver tea service when her father raised a numbered paddle and bid on an antique radio.

"What are you doing, Dad?" she asked, grabbing his hand.

"That's a fine radio. I'm going to give it to your mother as an anniversary present."

"Mother has been dead for nearly ten years now," she reminded him.

The old man's eyes momentarily narrowed with confusion, but when another bargain-hunter outbid him, he quickly raised the paddle again.

"Keep your hand down," Madge cautioned her father. "You don't want to buy that old radio. It probably doesn't even work anymore."

"Don't worry. If it doesn't work, I'll just take it out to my workshop and fix it, the same as I fixed your old Victrola."

"That was more than forty years ago. You don't have a workshop anymore. You sold that house after Mom passed away, and you've been living in the small apartment Regis and I had built for you over our garage."

"I don't have a workshop?" Melvin asked with disappointment as the auctioneer prepared to wind up the bidding on the radio.

"I've got fifty dollars. Do I hear fifty-five? That's fifty, going once, going twice, going ...."

Melvin's bidding paddle went up a third and final time, much to his daughter's dismay.

"Sold for fifty-five dollars to the gentlemen in the third row."

* * *

After the auction came to an end, Madge paid the cashier and made arrangements for the items she purchased to be picked up the following day by her shop's delivery truck. Her father, however, insisted on bringing the radio home with him in the car. The exasperated woman frowned and shrugged her shoulders. Why had her father wasted good money on a piece of junk?

When Melvin and his daughter got home, the old man immediately carried his prize up the stairs to his apartment above the garage.

"Dinner will be ready in a little over an hour," Madge called up to him. "Be sure to stay awake until then."

The old man placed the radio on the dresser and plugged it into the wall. He fiddled with the dials for several minutes and was then able to tune in to a news broadcast:

"It's practically standing still now; they've dropped ropes out of the nose of the ship, and it's been taken a hold of down on the field by a number of men. It's starting to rain again. The rain had slacked up a little bit. The back motors of the ship are just holding it, just enough to keep it from ... It burst into flames! It's burning and it's crashing! It's crashing terrible! Oh my, get out of the way, please. It's burning, bursting into flames and it's—and it's falling on the mooring mast and all the folks agree that this is terrible. This is one of the worst catastrophes in the world. And oh, it's burning, oh, four or five hundred feet into the sky. It's a terrific crash, ladies and gentlemen. The smoke and the flames now and the frame is crashing to the ground, not quite to the mooring mast. Oh, the humanity and all the passengers screaming around here. I told you. It's ... I can't even talk to people whose friends were on there. It ... It's ... I ... I can't talk ladies and gentlemen." 1

* * *

Following the emotionally charged news broadcast, Melvin listened to music until his daughter informed him over the intercom that dinner was ready.

"I'm sorry I'm late," the old man apologized when he noticed his daughter and son-in-law already sitting at the dining room table, eating their salads.

"It's a good day for a nap," Regis opined. "I wouldn't mind getting some sleep myself."

"I wasn't sleeping. I was listening to my new radio."

"You mean it actually works?" Madge asked with surprise.

"Yes, I was listening to Benny Goodman when you buzzed me."

Madge glanced at her husband, a secret exchange that said her father was having another "senior moment."

"Where are the boys?" the old man asked, looking at the empty dining room chairs. "Aren't they coming down to eat?"

Regis smiled at his father-in-law and replied, "They're all grown up now. Haddon is living in Baltimore with his wife and children, and Kevin is practicing medicine in Boston."

A look of confusion clouded the old man's features. His daughter turned away, not wanting to see his helplessness, not wanting to admit his increasingly frequent memory lapses might be indicative of a serious condition.

"So, you have a new radio, do you?" Regis asked, hoping to help bring his father-in-law through the maze of the past and back to the present.

"Yes, yes," Melvin cried excitedly. "It's an RCA cathedral style table radio. I believe the auctioneer called it a Suprette. And it was only fifty-five dollars—a remarkable bargain. Don't you agree, Madge?"

His daughter nodded her head perfunctorily.

"The first thing I did when we got back from the auction," Melvin continued, "was plug the radio in to try it out."

"And you heard Benny Goodman?" Regis asked.

"No. At first it was a news broadcast. Apparently, there was a serious plane crash in New Jersey."

"Really?" His daughter was suddenly interested in his story.

"Yes. A German airship caught fire as it was attempting to land at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station."

"The Hindenburg," Regis muttered.

It was a statement, not a question.

"Yes, that's the one. Have you ever heard of it?"

"Everyone is familiar with the Hindenburg," Madge told him. "It went down more than seventy years ago."

"You must have been listening to a special broadcast of historical radio programs," Regis offered.

"Yes, I suppose so," the old man agreed.

But a pall had fallen over the family gathered around the dining table, and the three people finished their meal in silence.

After dinner, Melvin joined his daughter and son-in-law in the family room where the three watched a DVD of Tom Cruise in Steven Spielberg's adaptation of War of the Worlds.

"Aren't the boys going to watch television with us?" Melvin asked. "Kevin likes science fiction movies."

"Kevin is a doctor now, Dad. He's a surgeon at Mass General."

"Oh, that's right. I forgot."

When the movie ended, the old man said goodnight to his daughter and son-in-law and went to his apartment above the garage. After showering and putting on his pajamas, he turned on the RCA Suprette and listened to an episode of Mercury Theatre in which Orson Welles presented his own version of The War of the Worlds, one far different from that presented by Steven Spielberg.

* * *

At breakfast the next morning, Melvin recounted for his daughter and son-in-law Welles's tale of Martians landing in Grover's Mill, New Jersey.

"The broadcast sounded so real that had there not been a disclaimer before the program, I would have believed New Jersey was actually under attack by spaceships from Mars."

Neither Madge nor Regis bothered to tell Melvin that Welles's famous performance was broadcast in 1939.

"I think we should consider getting my father on medication," Madge whispered when the old man went to the kitchen to pour himself a second cup of coffee.

"Do you believe that's really necessary?" her husband asked.

"His memory is getting worse."

"Maybe he only dreamt of the old radio show after seeing the Tom Cruise movie last night."

"Still, if he can't distinguish between his dreams and reality, then there's obviously something wrong and we ...."

She immediately changed the subject when her father reentered the room.

"More pancakes, anyone?"

"No, thanks. Two is enough for me," her husband replied.

Then he rose from the table and announced that he had some errands to run and wanted to get them done before the afternoon.

"Why? Have you got anything planned for today?" his wife asked.

"I'm going to watch game four of the American League playoffs."

As one of the few Yankee fans living in Massachusetts, Regis was actually enjoying the postseason games. Madge, who did not care for sports, opted to spend the day shopping.

"Feel like going to the mall with me, Dad?" she asked her father after she finished her housework.

"No. I'd rather watch the game with Regis."

"Will you be okay here by yourself until he gets back?"

"Sure. Why wouldn't I be?"

Madge forced a smile but silently prayed her father would not set the house on fire or wander off while she was gone.

Left alone to his own devices, Melvin went to his small apartment where he took a can of cold Coca-Cola out of the small refrigerator, popped the top and turned on the RCA cathedral style radio. It was a broadcast from Yankee Stadium, a farewell speech by Lou Gehrig:

"Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about a bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the Earth ...." 2

When Melvin went down to the family room later that afternoon, his son-in-law was sitting in his recliner in front of the plasma TV. The game was already in the middle of the third inning.

"Any score yet?" the old man asked.

"Yeah. The Yankees are ahead three-nothing," Regis happily announced.

"Speaking of the Yankees, I heard Lou Gehrig on the radio this morning. Did you know he's quitting baseball?"

Regis realized his wife was right. His father-in-law most likely did need medication.

* * *

When Madge described her father's symptoms to the family physician, the doctor referred him to a neurologist who concluded that the elderly patient was in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Melvin took the news in stride. He had lived a long, full, happy life and had no fear of dying. He only hoped he would not become a burden on Madge and Regis, so he took his medication faithfully and spent many hours doing crossword puzzles and playing word games in an effort to keep his mind alert.

After retiring to his room every night, Melvin continued to play his radio. Initially, he failed to notice the chronology of the events described in the broadcasts. They began with the destruction of the Hindenburg in 1937 and continued through the end of the Thirties. With FDR's December 7 ("a date which will live in infamy") speech, they entered the Forties. The major events of World War II, the armistice and the postwar era were followed by Elvis Presley, the Korean Conflict, McCarthyism and the Rosenberg trial.

By the time Christmas arrived, Melvin's radio had entered the turbulent Sixties: the Cuban Missile Crisis; the John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., assassinations; the war in Vietnam; and Neil Armstrong's giant leap for mankind. With the New Year came the long-awaited peace in Southeast Asia, the Watergate scandal and Nixon's resignation. February brought with it more snow as well as the Iran Contra Affair, Reaganomics, the Gulf War and the breakup of the Soviet Union.

During the course of roughly four months, Melvin had heard presidents come and go, wars start and end, the economy rise and fall and people grow old and die. Finally, as March ushered in the spring, the RCA Suprette entered the new millennium: the September 11 attacks on the Pentagon and World Trade Center, the war on terrorism, Hurricane Katrina and the capture and execution of Saddam Hussein.

* * *

"I think the Aricept is helping my father," Madge optimistically told her husband one Sunday morning in early June.

Regis agreed with her.

"He's not mixing up the present and past nearly as much as he did."

Unfortunately, the couple's happiness at Melvin's improved mental state was short-lived. As spring turned to summer, the old man became increasingly silent and withdrawn. He no longer told his daughter and son-in-law about his radio broadcasts, for he did not want to upset them with the news.

During the first week of May, the radio had crossed the boundary between past and future with only a brief layover in the present. The events it foretold were devastating: genocidal wars, terrorist attacks, natural disasters brought about by global warming and epidemics of biblical proportion would, according to the broadcasts, reduce the Earth's population by nearly ninety percent. The people who were left alive would be plagued by a bankrupt economy, rampant disease and a severe shortage of food and natural resources.

Things came to a head in the Strickland household one day when Madge went into her father's apartment to give him his medicine and found him sitting on his bed, crying.

"What's wrong, Dad?" she asked with concern.

"The news ... on the radio ... it's all so terrible," he sobbed.

"Why do you listen then? If it's going to upset you like this, I'm going to get rid of that radio."

"It won't matter," the old man declared after he managed to get his emotions under control. "It's all going to come to an end."

"What are you talking about?"

"This radio," he explained. "It used to tell me things that happened in the past, but lately ...."

His voice trailed off.

"What, Dad?" his daughter prompted.

"It tells me things that will happen in the future. I didn't want to tell you this, but the world is going to come to an end. Mankind will be destroyed. The Earth will be devoid of all life: both plant and animal."

"That's it!" Madge exclaimed. "I've had enough."

She crossed the room, pulled the plug out of the wall and took the radio down to the garage where it would remain until Regis could take it out with the trash.

Upstairs in his apartment, Melvin swallowed his pills down with a glass of water and lie down on his bed, resigned to the horrible fate that awaited the world.

By morning, he was dead, his heart having given out during the night.

* * *

Madge Strickland wiped the tears from her face with a tissue as she sorted through her father's belongings, placing most of them in boxes to donate to the Salvation Army. Melvin Hardy's death had been bittersweet. While his daughter hated having lost a beloved parent, she took comfort in knowing he would be spared having to endure the mental disintegration of advanced Alzheimer's.

Regis, meanwhile, was carrying boxes down to the garage and placing them in the antique shop's delivery truck.

"What do you want to do with this?" he asked as he walked into the room, carrying the RCA cathedral style radio. "I found it in the garage."

"Just throw it away."

"Why? I plugged it in downstairs, and it works fine."

Madge stared with revulsion at the radio as though it were a poisonous snake about to strike.

"Get rid of it!" she cried. "Take a hammer and break it up."

Regis raised his eyebrows and sighed.

"All right. But you could probably get a hundred bucks for it in your shop."

"I want it destroyed—now!"

Regis took the Suprette down to his workbench, picked up a hammer and brought it down on the radio. The sound of splintering wood echoed through the garage. It took him several good swings to break the wooden case.

"Well, I'll be damned!" he exclaimed with awe.

"What?" his wife asked, suddenly appearing behind him.

"There are no tubes or anything inside this radio. It was basically nothing but an empty wooden box."

He scratched his head with consternation.

"How in hell did it ever work?"

Madge took the hammer from her husband's hand and gave the broken case a few good whacks herself.

"I don't care how it worked, as long as it never works again."

* * *

Curly Hickman jumped down from his perch when the sanitation truck slowed to a stop. He grabbed the handles of the first garbage can, lifted it over his head and emptied its contents into the truck. He then tossed the empty can onto the Stricklands' lawn and picked up the second.

As he raised the half-full can above his head, a vintage radio fell out onto the ground: an RCA Suprette cathedral style table model.

"Shame to throw something like this in the garbage. Even if it doesn't work now, I can probably tinker with it and get it working."

He placed the radio inside the cab of the truck, returned to his perch and signaled the driver to continue to the next house on the route.

1From Herb Morrison's coverage of the Hindenburg crash on May 6th, 1937.

2From Lou Gehrig's farewell speech at Yankee Stadium on July 4, 1939.

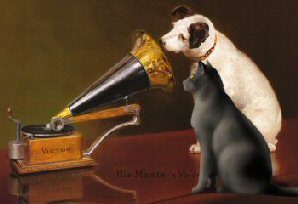

Salem insists both he and Nipper were in the original RCA logo until he became a victim of downsizing.