Awake

"I can't believe a man as wonderful as Bramwell Whitcomb wants me to be his bride!" Theodosia Piggott exclaimed as she prepared for her big day.

"You make it sound as though you're some poor waif of a girl with nothing to offer a man," Hermione said, helping her sister get into the voluminous wedding dress. "Our family is as aristocratic as his, and our home is as nice as theirs. And you, my dear baby sister, in case you hadn't noticed, are a beautiful girl with many accomplishments."

"I can paint a little," the bride said, grossly underestimating her talent. "Big deal! Bramwell is a genius! A doctor and a scientist who studied at the finest universities: Vienna, Prague, London, Paris. I don't know how he can bear to listen to my silly prattle without being bored to death."

"Frankly, I'd rather hear you talk about poetry, music and art than listen to him go on and on about anatomy and all those diseases he hopes to cure. Who wants to hear about lung ailments and tumors, anyway?"

"I find his work fascinating! In fact, I find everything about him fascinating. Honestly, if the world should end tomorrow and only Bramwell and I survived, I would still be happy. I adore him! I love him to the exclusion of everything else."

Hermione had never seen a woman so besotted with a man as her sister was Dr. Whitcomb. Despite the difference in their ages, she was head over heels in love with him. In a way, the older sibling envied the younger one. Her own husband, although a kind, amiable and dependable man, did not make her pulse race. Their marriage was a happy, comfortable one, but it lacked the grand passion so often found in love sonnets and romantic fiction.

I only hope for her sake my sister doesn't someday discover that the idol she holds on a pedestal is only human, Hermione thought as she carefully placed ribbons in her sister's curls. I would hate to see her heart broken and her spirit crushed.

Two years into the marriage, Hermione's fears seemed unfounded. Theodosia and Bramwell were every bit as happy as they were on the day they were wed. All that was lacking in her sister's life was a child.

"You're not yet twenty," the older sibling pointed out. "You have plenty of time for a family."

"That's easy for you to say. You've got three children already."

"That's to be expected. I've been married longer than you."

"There are women that can't have children," Theodosia said, revealing her innermost fear. "I would be content to wait if only I knew I wasn't one of them."

"Your husband is a brilliant doctor. If there is something medically wrong with you, I'm sure he will be able to fix it."

"He is a genius!" her sister agreed, gushing with pride for the man she married. "I have all the faith in the world in him."

That faith, born of love, nevertheless was misplaced. Even in our technologically advanced world of the twenty-first century, medicine can do just so much. People still die from diseases that are incurable. Given the comparatively limited medical knowledge of the nineteenth century, easily treatable illnesses in our time were death sentences then. Thus, no matter how brilliant Bramwell Whitcomb was, he was helpless in the face of the ovarian cancer that was to claim his young wife's life.

By the time the couple's third anniversary approached, Theodosia was confined to her bed, slowly wasting away. All her husband could do was give her something to ease the pain and help her sleep. Her family kept a vigil at her bedside, trying to project optimism and good cheer, but the young woman knew she was dying. Towards the end, she even looked forward to her death.

"I wish I could just die already," she moaned.

"That's enough of that talk!" Hermione chastised her. "You've got so much to live for. There's your husband, and you always wanted a child."

"You don't have to pretend for my sake. I know I don't have much time left. I've accepted my fate. I only wish I wasn't such a burden for everyone around me."

"Burden? Don't be silly. We love you, and we want to be with you for as long as possible."

"Dearest Hermione," Theodosia said, as the healthy woman bathed her brow with a cool cloth. "You have been a great comfort to me. No woman ever had such a wonderful sister."

Those were the last words Theodosia Whitcomb ever spoke. She slipped into a coma that evening and died three days later.

* * *

I awoke to a darkness so complete that I had to wonder if my eyes were open or closed. There were no shadows, no shades of gray, just complete blackness. I tried to move, but my limbs felt as though they were weighted down. Even turning my head proved too difficult a task.

"Wh—"

It was a barely audible sound, not even a full syllable much less a word. It was more like an exhale of breath.

A single question screamed in my head: "What's wrong with me?" At least my brain worked. I was capable of thought, if not speech or movement.

I lay there for several minutes before realizing there was no pain. It had been such a constant in my life as of late that it seemed part of me, like the beating of my heart. Whatever new medicine my beloved Bramwell was giving me was working. Could it also be causing my lethargy? Was it so strong an analgesic that it left me completely drained of energy? If so, was the cure worse than the cancer? Did I want to remain completely immobile for whatever time was left to me? Unable to move, unable to speak, unable to ....

That was the moment I realized there was no gentle rising and lowering of the chest, for I was no longer breathing!

There are moments in the happiest of lives when fear strikes. I had known more than a few myself. For instance, there was the time when, as a child, I wandered into the woods and could not find my way out. Distress caused two pronounced physical changes: I breathed faster and my heartbeat quickened. I was afraid now, yet there was no resulting change in my body. I already knew I was not breathing, and it also seemed my heart was not beating either.

How is that possible? No medicine—no matter how strong—was capable of causing such a death-like state in a living being.

As I lay in the dark, helpless, I felt my limbs slowly gain strength. After putting forth a great deal of effort, I was able to move the pinkie finger of my right hand. It moved barely an inch, but it was a start.

I tried speaking again.

"Wh—"

It was the same sound but louder this time.

Is the medicine wearing off? It might be. But there was still no pain. Quite the opposite. I felt nothing. I could not feel the bed beneath me—was it a bed?—or the clothes on my body. I was not even capable of sensing temperature. I was neither warm nor cold. Loss of tactile sensation was not my only problem. My auditory and olfactory senses seemed to have abandoned me as well.

Something must be terribly wrong! I can't see, hear, smell, feel or move. I wanted to cry, but, apparently, I was incapable of doing so. Instead, I waited. (What else could I do?) I waited and waited and waited. Gradually, my senses began to come back to me. My hearing was restored first. The first sound I recognized was my darling Bramwell's voice.

"Theodosia, dearest?" he asked anxiously. "Are you awake yet?"

I wanted to scream, "Yes! Yes, my love!" and hurl myself into his arms, but I was still incapable of speech and movement. I could not even see his handsome face.

"Dear God," my husband prayed aloud, "please let her open her eyes."

There was anguish in his voice. Clearly, he feared my time had come. Still, his prayer took me by surprise. As a man devoted to science and the pursuit of knowledge, he never expressed any faith or showed a leaning toward a specific religion.

My sense of smell—arguably the least useful of the senses—was restored next. I caught the scent of soap. The sound of footsteps. These were things I had always taken for granted. Now I realized how precious they were. When will I be able to see again? To feel? To move? To speak? Impatient as I was, I knew I could do nothing but wait. And wait I did!

Finally, after what seemed like days had passed, I found the strength to raise my eyelids. Oh, so slowly the darkness faded like an early morning fog dissipating in the sun. I was no longer in my room; I was in Bramwell's laboratory.

I was lying on the table, valiantly attempting to move my jaw and produce an identifiable sound, when the door opened and in walked my husband. He looked at me, and the expression on his face was instantly transformed from one of wretchedness to one of joy.

"Theodosia!" he cried and ran to my side. "My dearest love, you're awake!"

He put his lips on mine and kissed me, yet I felt none of the thrilling titillation his kisses had always elicited in the past.

There were tears in his eyes when he pulled away, tears not of sorrow but of happiness.

"You have no idea how glad I am to see your beautiful blue eyes looking up at me again," he declared, gingerly touching my hair as though he wanted to assure himself that I was no hallucination.

Despite the confused state I was in, I longed to return his words of affection and devotion. I wanted to tell him how much I loved him, but all I was capable of uttering was the pathetic "wh—" sound.

"Don't try to speak, darling," Bramwell cautioned. "You don't want to exert yourself. You need to take things slowly. In a few days, you'll be strong enough to get up on your feet. We'll talk then."

Get up on my feet? What was he talking about? Since cancer sent me to my bed, my family had tried to keep up my spirits and give me hope by talking of a future I would never have. But my husband had always been honest with me. Yet now he spoke as though I were on the road to recovery rather than an early grave.

"Close your eyes and go to sleep. You've been through so much, you deserve to rest. I'll stay here by your side."

He pulled a chair up next to me, sat down and took hold of my hand. I closed my eyes as he had suggested and promptly fell asleep.

I slept on and off for what must have been close to a period of three to four weeks. Every time I woke from my slumber, I was physically stronger and my senses more acute. At last, with Bramwell's help, I was able to get down from the table and walk across the room.

"That was wonderful!" my husband cried with encouragement. "You're doing so well, my love!"

Despite not having been out of bed for many months, I felt no strain in my muscles. My efforts had not even tired me.

"Are you hungry, dearest?"

It occurred to me then that no food or beverage had passed my lips since the day I awakened in my husband's laboratory. How was I receiving nourishment? My husband gave me medication four times daily. It must have also provided the nutrients my body needed.

"I know you can't speak yet, but if you want something to eat or drink, nod your head."

Since I wasn't the least bit hungry or thirsty, I moved my head from side to side to indicate a negative response.

"Maybe later your appetite will improve."

Bramwell then lowered his eyes, as though he were unwilling to let them meet mine.

"Why?" my brain asked itself. "What was wrong?"

"I think you had enough for today. Let's get you back on the table."

But I didn't want to lie down again. I had seen enough of the laboratory, and now that I was capable of walking, I wanted to return to the main section of the house. I tried to resist his efforts to lead me, but I was not quite as strong as I had imagined. Although I had a will of my own, my body would not go along with my desires.

When am I going to be fully recovered? I wondered. When will I get my voice back? When can I resume the life I left behind the day cancer knocked on my door? These questions and more tortured me, but I was unable to ask them.

I stopped resisting. Like a docile child, I was led back to the table. My husband instructed me to lie down, and I obeyed. Once in a recumbent position, I closed my eyes, not because I was tired but because I was bored. There was little else for me to do but sleep.

Another week would pass before I could finally force a word out of my mouth. It began with my now familiar "wh—" sound, but on my second attempt the "—at" followed.

"What?" I clearly asked.

Summoning every ounce of strength and will power I could muster, I uttered a second word.

"Wrong?"

"You can talk!" Bramwell cried with joy. "I prayed this day would come!"

I didn't want to hear about his prayers; I wanted an answer to my question.

"What?" I repeated with great difficulty.

"You want to know what's wrong?" he asked.

I nodded my head.

"Nothing is wrong. I'm fine. I'm beyond fine. I'm absolutely delighted."

I shook my head from side to side and forced out two more one-syllable words.

"With ... me."

"What's wrong with you? Nothing. You're perfect!"

Even though I was regaining my ability to talk, I was still unable to communicate my thoughts. I rolled my eyes in frustration. Bramwell sensed my vexation, and the smile vanished from his face.

"You must have questions."

I vigorously nodded my head.

"There was something wrong with you, my darling. You had cancer."

His use of the past tense verbs was and had confirmed my assumption that he had worked a miracle. My genius husband cured my cancer. I tried to add two more words to my expanding vocabulary—thank and you—but all I got out was the initial "th—" before my beloved revealed the shocking truth.

"You died."

What? Did I hear him correctly?

"I tried to save you, but all my efforts proved futile. The cancer finally won."

No! That can't be true. What was it the philosopher René Descartes said? "I think, therefore I am." I'm quite capable of thinking; therefore, I must be alive!

"We had a funeral for you," Bramwell continued, to my horror, "after which your body was laid in the family crypt. I quickly removed you from that place of death and put you in a chemical solution that I devised to keep your body from decaying. You remained in that vat for three months until I could perfect a serum to restore you to me. It's taken nearly a year for you to recover from the ordeal, but you are doing exceptionally well."

Once I was over the initial shock of my death, I attempted a two-syllable word.

"Can ... cer?"

"You don't have to worry about that anymore. It's hard to explain, but although you're no longer dead, you're not exactly alive either."

Not exactly alive? What the hell does that mean? I wondered.

"Your body is—for lack of a better word—frozen as it is. Your cells no longer reproduce. You probably already noticed that you don't breathe anymore. You have no heartbeat, and blood no longer flows through your veins. Apparently, that's why you have no appetite. There's no need for you to eat to sustain normal body functions."

So, basically, I'm like a puppet, a marionette capable of moving without strings. But, no, that's not true. I have a mind. Yes, Monsieur Descartes, I do think; therefore, I definitely am! Call it what you will, I'm alive! Or, at the very least, I am awake from that eternal sleep known as death.

From the day I learned the astounding truth about my death and rebirth, I embraced my new existence. There were advantages in being "awake" as opposed to being "alive." There was no need for me to eat or drink, nor did I require sleep. My husband's initial belief that rest would aid in my recovery had been wrong. Time alone was all that was required.

As the weeks passed, my power of speech improved to the point where I encountered no difficulty communicating my ideas. I also left the lab and had free range of Whitcomb Manor, my husband's ancestral home. However, no one had yet informed my family of my resurrection.

"We can't just spring this news on them," Bramwell said. "We have to wait for the right time."

"When will that be?"

"Once they're past the worst of their grief, they'll be more likely to listen to reason."

"I don't follow you."

"Your family are devoutly religious. They might believe my bringing you back is against God's will."

"That's ridiculous! If God really wanted me dead, why would he have given you the knowledge to wake me up?"

"You may feel that way, but I'm not so sure your family will. Let's just wait for a while before we tell them."

Although I missed my parents and sister terribly, I agreed to my husband's wishes. I had, after all, taken a vow to honor and obey him. As a loving wife, I was always obedient. He was the man; therefore, he knew best. Did Monsieur Descartes say that, too?

Since my former friends and family thought I was dead, other than my husband, the only people I saw were the servants at Whitcomb Manor. These were loyal family retainers, many of whom worked for Bramwell's parents when they were alive. As such, they swore to keep my existence a secret. But they were not company for me during those long hours that my dearest was kept busy in his laboratory. Even if it were considered socially acceptable for the mistress to associate with servants, none of the household staff wanted to be around me. Whenever I encountered one of them, he or she would look at me with fear and revulsion.

"They're all afraid of me," I complained to Bramwell.

"What did you expect, my dear? They're a superstitious bunch. They know nothing of science and medicine. They probably think a magic spell made you rise from the dead."

"So, they think I'm some kind of monster? Maybe they fear I'll drink their blood, like a vampire."

"Don't pay any attention to them."

"But I'm lonely. When you're shut away with your work, I have no one to talk to. Maybe we could tell my sister ...."

"No! It's too soon to tell your family."

"But ...."

"I'll decide when the time is right."

"I'm bored. I have nothing to do all day."

"Why don't you try reading a book. We have an excellent library here at the Manor. Why don't you take the opportunity to improve your mind?"

Was there a hint of dissatisfaction in my husband's suggestion? Was he getting tired of having an intellectually inferior wife? My old insecurities came back. Bramwell was a genius, capable of working medical miracles. What could he possibly see in me?

"That's a wonderful idea," I agreed. "There's so much I've always wanted to learn about."

"Good," he said dismissively, as he got up from the dining table and returned to his lab.

I was bereft. I had no family, no friends. People feared me and, worst of all, my husband seemed disappointed in me. If my body were capable of producing tears, I would lay my head down and have a good cry. However, I could no longer weep. It was but one item on a long list of things living people could do but I couldn't.

From that day on, my life became a series of books, which, at first, I read with a voracious appetite. Ultimately, however, my studies began to sadden me. Why read about exotic places that I could never visit? About adventures I would never have the opportunity to take, people I would never meet and experiences I would never enjoy. They say a man's home is his castle; my home became my prison. My family still believed me dead. The servants continued to avoid my presence, some even made religious gestures when they saw me as though to ward off evil.

Far worse, in my mind, was how my feelings for Bramwell changed. Roughly eight months after I "woke" from death, the first fleeting feelings of resentment stirred in my breast. The love I felt for him still took center stage in my heart; however, the gratitude I initially felt at being saved gradually faded. I tried to push those disloyal thoughts aside, but they kept sneaking back into my brain.

Then came the day my husband surprised me with a celebratory party. It was not a large celebration since there were just the two of us in attendance. However, he had an elegant meal prepared, opened a bottle of fine wine, decorated the room with fresh flowers and placed a gift on my dinner plate.

"Happy ... uh ...."

He stopped his toast, unsure of the proper word to use. His glass of wine remained midair as he considered his choices.

"It's not really your birthday, so I assume this is more of an anniversary. Yes. Happy anniversary, my dear."

"An anniversary of what?"

"It was one year ago today that you returned to me."

"Oh."

There was no hint of merriment in my voice, nor did I pick up my wineglass in acknowledgement of his toast.

"Why don't you open your present?"

I did as he suggested. Inside the small box was a pair of sapphire earrings.

"Thank you."

"You're more than welcome, my love. Now, let's celebrate!"

The food on my plate failed to tempt me. This was not surprising since I had hardly eaten anything the past year.

"Even if you're not hungry, you might enjoy the taste of the food."

I took a bite, just to please him.

Why must I do everything to please my husband? I suddenly wondered. He is not the one who suffered with the pain of cancer for months on end. His life had not ended at the young age of twenty-three. He was thirty-two years old and in good health. He might have many decades left to him. Furthermore, he could walk out the door and into the world without fear.

"Don't you like it? Would you prefer to have your dessert now instead? You always did have a fondness for sweets."

As I looked down at my plate, all that I had endured for twelve months seemed to gnaw at my brain. With a sense of shattering revelation, it occurred to me that Bramwell did not bring me back from the dead for my sake. His motives were purely selfish.

"Why did you do it?" I asked, not daring to lift my head and look at him.

"Do what, dearest? Arrange this celebration? Buy you the earrings?"

My anger grew, and I found the courage to stare him in the eye.

"Why did you bring me back?"

"Isn't it obvious? I brought you back because I love you."

"Didn't it ever occur to you that I might not like being in an existence that is neither alive nor dead?"

"Frankly, no. Why aren't you happy?"

"Figuratively speaking, I have nothing to live for. I have no friends, family. I can't go anywhere or do anything. I've even been denied what every woman wants most: a child."

"You have me. We have each other."

That's not enough, I thought.

That realization caused my world to tumble down upon me. For so long, Bramwell Whitcomb had been the center of my universe. Like a planet orbiting its sun, I planned and lived my life around him. All of a sudden, I felt as though my sun had disappeared and I was cast out in space, alone and adrift in an endless nothingness.

I must put a stop to it!

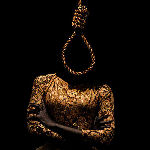

I first attempted to end to my painful and meaningless existence one week after the anniversary of my awakening. Hanging was my method of choice. With one end of a rope tied around my neck and the other end to a rafter in the ceiling, I kicked out a stool beneath me. The rope went taut, and my body hung suspended, six inches above the floor. For more than an hour, I waited to die, but nothing happened.

Foolish me! How could I hope to strangle myself, cutting off my air, when I was incapable of breathing? My second attempt was just as pointless, as were my third, fourth and fifth. Drowning, like hanging, can't kill a person who doesn't breathe. Throwing myself down a staircase did not even cause a bruise, much less death. The poison I swallowed would no doubt have killed me had my heart not already permanently stopped beating. And cutting my wrists and throat did not produce a single drop of blood, much less death.

With each failure, I became more determined to succeed, more eager to die.

My sixth and final attempt was made in desperation. After dousing my dress with lamp oil, I set myself on fire. As fate would have it, Bramwell entered the room just as I burst into flames. In attempt to pull the burning garment from my body, his own clothing caught fire.

In short, he died and I survived.

The servants called the authorities. My beloved's body was taken away, and I was accused of his murder. I offered no defense. On the contrary, I readily confessed to a crime I did not commit. I wanted to be convicted and sentenced to death, which I duly was. The penalty for murder was hanging, and I was forthwith sent to the gallows. The hangman, believing I was a mortal woman, put the noose around my neck and pulled the lever to release the trap door. I could have told him that particular method of execution would not work, but he had to find out for himself.

Three times he went through the motions, and all three times he failed to kill me.

"I ain't never seen anything like it!" he exclaimed. "I hate to keep putting you through this, but I'm going to have to try again."

"Go ahead and give it your best," I told him. "It won't do you any good though. You can't kill me; I'm already dead."

Only after the executioner and the jailers failed to find a heartbeat were they willing to believe my explanation.

"Your husband restored you to life and yet you killed him?" the magistrate asked, disgusted by my ingratitude.

"It was an accident, not murder. I wanted to kill myself. Bramwell caught fire trying to save me."

"Why are you telling us this now? Why didn't you say something at your trial?"

"Because I want to be executed. I'm unable to kill myself. I felt sure the law would find a way to put me out of my misery."

"I've never knowingly ordered an innocent person to be executed," the magistrate said.

"Please! I beg you! God intended me to die; that's why I was stricken with cancer. Bramwell had no right to go against his divine will and bring me back."

"I suppose, technically, it wouldn't be murder if we execute you since you're already dead."

"Yes! Please have mercy on me, your honor, and end this miserable existence."

"All right," he conceded after giving the matter careful thought. "But we'll have to find an alternative means of execution. Hanging obviously won't do the job."

The following day I was led out to the prison yard. The same clergyman who had attended my hanging was in attendance again, repeating the same prayers. His "amen" was the cue for me to kneel and place my head on the tree stump that had been brought in specifically for my execution. Rather than the hangman, a woodsman, skilled with an axe, was called in to perform the act. My hair was tied up and my collar loosened, to bare my neck and provide him with a good target.

"I'm sorry, ma'am," he apologized.

"There's no need to be. I want you to do this," I assured him.

He mumbled a prayer, asking his maker for forgiveness, and then raised the axe above his head. I closed my eyes. Thoughts of Ann Boleyn and Mary Queen of Scots flooded my brain as I waited for the weapon to fall.

It was a clean decapitation, taking only one blow to sever my head from my body.

* * *

The woodsman tossed the bloody axe aside, leaned over and vomited.

"I hope we never have to do anything like that again," the ashen-faced magistrate declared.

"Take comfort in knowing she's at peace now," the minister told those who witnessed the beheading.

A crude wooden coffin was brought to the prison yard. The two men who carried it were tasked with the unenviable task of disposing of the remains. After the body was placed in the box, one of the men leaned over to pick up the head. That was when Theodosia opened her eyes.

"Jesus Christ!" the poor man screamed in fright. "She's still alive!"

"Don't be afraid," the clergyman assured him. "It's just a reflex action. I assure you she's dead."

"That's right," the head spoke. "I am dead, and I have been since cancer took me nearly two years ago."

When the workman's helper saw the headless body rise from its coffin, he fainted dead away.

"The beheading didn't work. What are we going to do now?" the minister asked the magistrate.

"I don't know. I suppose we'll have to find another way to carry out the execution."

"And if that doesn't work either?"

"Then we'll keep on trying. Science brought her back. I'm sure, in time, it can find a way to correct that mistake."

"I hope so," the woodsman added, wiping his mouth with his sleeve. "It would be a damned shame to condemn anyone to such an existence."

Shame or not, more than two centuries later, the two parts of Theodosia Whitcomb—her body and head, both dead yet awake—still wait in desperation for a second medical miracle to happen and for a merciful end to her torment.

Alive or dead, asleep or awake, Salem will never lose his appetite!