Day at the Circus

Norris Goddard was determined not to make the same mistakes with his young grandson that he had with his own child. Overall, he had been a good father. He loved his son, Fordham, very much, taught him right from wrong and provided amply for all his needs. Unfortunately, Norris, like many other men of his generation, had devoted far too much time to his job and in doing so had missed out on a good portion of his son's childhood.

Coco, Norris's wife, had done more than her fair share in raising the boy. She had served as den mother for Fordham's scout troop, attended all his school functions, cheered at his Little League baseball games, helped him with his homework and counseled him about girls, dating and sex. There is little doubt she had been an exceptional mother and, in all likelihood, would have been a wonderful grandmother as well. Sadly, however, Fordham's son was only a year old when Coco died.

Shortly after the death of his wife, Norris retired from his job at the home office of New England Life and Casualty Company. No longer burdened with ten- and twelve-hour work days, he acutely felt the loss of his family. The old house—once filled with the sound of laughter—was quiet and empty. Norris felt like a ghost haunting the memories of his past, and he didn't like it one bit.

"This place is too big for you, Dad. Why don't you sell it and move in with Carol Anne and me?" Fordham suggested. "You can stay in the spare room over the garage; that way you'll have plenty of privacy."

"I wouldn't want to be an imposition on the two of you," Norris protested weakly although such a move was exactly what he hoped for.

"I think it would be the other way around," his son jokingly said. "You know if you do move in with us, we're going to be asking you to keep an eye on Nate quite a bit."

"That would be my pleasure! There's nothing I'd rather do than spend time with my grandson."

Being a full-time grandfather brought new meaning to Norris's life. Despite the difference in their ages, he and Nate became good friends. Once her father-in-law moved into the spare bedroom above the garage, Carol Anne Goddard went back to work. It was Norris who took the young boy to preschool each morning and picked him up afterward. On warm, sunny afternoons, the proud grandfather would take his grandson to the neighborhood playground after school.

One day, as Norris pushed the boy on the swing, Nate turned around and asked him, "Did your grandfather watch you when your mommy went to work?"

"No, my stepmother didn't have a job. She was what is now called a stay-at-home mom."

"What's a step-mother?"

"Although she was my father's wife, I wasn't her son. You see, I lost my real mother when I was a very young child—much younger than you are now, in fact."

"You lost your mother? Didn't you ever find her again?"

"I didn't lose her like you lost your father's baseball mitt last month. You're a little too young to understand this, Nate, but my mother—well, she ... passed away."

"You mean she died and went to heaven?"

Norris smiled and realized he had underestimated his grandson's intelligence.

"That's right. My mother died, and my father later remarried. That woman became my stepmother, and she helped my father raise me."

The playground was only one of many places Norris took his grandson. The two of them often spent time at the lake where the old man taught the boy to fish, swim and skip rocks across the water. They also made frequent visits to the local petting zoo, the baseball field, the children's museum and the movie theater.

It was while Norris and Nate were at Funland, a small family-oriented amusement park, that the boy saw an antique calliope.

"Look at that, Grandpa," he cried with excitement. "What is it?"

"It's a calliope," Norris replied.

"What does it do?"

"It's a musical instrument, a lot like an organ or a piano."

"Why is it on wheels?"

"So that it can be driven in a parade. Years ago, circuses often used parades to draw people to the show."

Nate's eyes lit up like a Christmas tree.

"Are there any circuses around here?"

"I don't really know. Ringling Brothers—that's the granddaddy of all circuses—most likely only goes to Boston, but there might be a couple of smaller, independent circuses that play somewhere around Rockingham County."

"Can we go see one?"

"Okay, but only if it comes close to here. If not, you'll have to ask your parents to take you to Boston. At my age, I don't like to drive that far."

* * *

The Gunther Brothers Traveling Circus was a small, family-run organization that toured small towns up and down the East Coast, giving performances on behalf of volunteer fire companies, children's hospitals and other worthy charities. Unfortunately, Gunther Brothers only played the eastern New Hampshire area in June.

"We'll have to wait until next year," Norris told his grandson.

Naturally, the boy was disappointed. To a young child, a year seemed an eternity. When the summer ended, however, the autumn brought with it all new delights: jumping into piles of raked leaves, trick-or-treating on Halloween, feasting on Thanksgiving and then, shortly afterward, celebrating the Christmas season. It wasn't until April that the subject of the circus came up again.

"It's hard to believe when you look out the window and see all the snow on the ground," Grandpa said, "but the circus comes to town in only two months."

Eventually, the warm spring sun melted the New England snow and ice. Shortly thereafter, the first hardy spring flowers emerged from the cold soil. May brought sunshine, rising temperatures and longer days. Finally, June arrived, and bright, colorful posters announcing the arrival of the Gunther Brothers Circus in nearby Madison began appearing all over Rockingham County.

* * *

On the northwestern side of Madison, seven miles from the center of town, was the abandoned Madison Drive-in Movie Theater. The drive-in, which had fallen victim to rising movie prices and the growing popularity of cable television and video rentals, closed during the early Nineties. The property on which it once stood was now overgrown with weeds and littered with trash. Each June, however, the Madison Volunteer Fire Department cleared the empty lot in preparation for the annual arrival of the Gunther Brothers Circus.

"Are you sure you two don't want to go?" Norris asked his son and daughter-in-law before purchasing advance tickets.

"We're sure," Fordham replied. "I don't care for circuses, and, frankly, Carol Anne and I would like a night out at a restaurant that doesn't ask us if we want fries with our meal."

"Then I'll just take the boy. I don't know if we'll have any fries or not, but we can eat hot dogs, cotton candy, peanuts, popcorn, snow cones ...."

"Hold on, Dad," Carol Anne said with a laugh. "Nate will be sick to his stomach if he eats too much junk food!"

"Okay," Norris laughingly conceded. "I'll limit his food intake to a hot dog and a cotton candy."

* * *

From the day he purchased the tickets, just three weeks before the arrival of the circus, Norris experienced disturbing dreams—nightmares actually. For the first time since he was a small boy, he dreamt of his mother. Norris had been too young to remember her, but his father had given him a handful of photographs, so he knew roughly what she looked like. The daughter of two Irish immigrants, Geraldine Goddard had carrot-red hair, green eyes and a fair, freckled complexion.

In those disturbing dreams, Norris was a small child again, crying for his mother. Despite her son's piteous wails, the woman did not respond. Norris would wake up from his sleep, his brow damp with perspiration and his heart racing wildly.

Why, after all this time, am I dreaming of my mother? he wondered.

True, he had been devastated by his parent's death, but she had died more than sixty years ago. Coco's death had affected him far more deeply and had been much more recent. In fact, he still had not gotten over losing her, yet he had no disturbing nightmares about his wife.

* * *

Fordham and Carol Anne stood on their front steps and waved goodbye as Norris and his grandson got into the car.

"Have fun, you two," Carol Anne called. "And watch that junk food."

"Off we go, buddy," Norris announced happily as he buckled his grandson into his car seat. "Our next stop is the circus."

Their home was only twelve miles from the defunct Madison Drive-in, but it took close to an hour to get there due to the heavy traffic on the one-lane road.

"Looks like everybody in town is going to the circus," Norris said as he pulled off the road onto a large grassy field.

A Madison volunteer fireman waved a fluorescent baton, indicating where the circus patrons were to park.

"You stay close by me, Nate, and hold on to my hand," the cautious grandfather warned when the two got out of the car. "I don't want to lose you in this crowd."

Norris and his grandson followed the other patrons across the field to the midway where vendors hawking their wares tried to be heard over the sound of loud rock music, noisy power generators and screaming children.

"I want to ride the ponies, Grandpa," Nate cried, tugging on the old man's hand when he saw several small children on horseback being led by animal handlers.

"Wait a minute, there, buddy; we have to get tickets for the rides."

It was while Norris was standing in line to purchase tickets for the pony ride that he saw for the first time the blue-and-white-striped circus tent: the big top. A strange sensation—not a true pain, but more like a dull ache—fluttered in his chest, and his respiration quickened. At first, he feared he was going to have a heart attack, but after a few moments, the symptoms passed.

Grandpa purchased the ride tickets and watched as Nate was led around the track on the back of a white pony. Norris took his camera out of his pocket and snapped a few shots of the happy youngster. Photographs made up the majority of his memories of Fordham's childhood, photographs Coco had taken while he was out selling life insurance. Now more than ever he wished he had spent less time at work and more time with his wife and son. He would have liked to have seen Fordham's face when he hit a game-winning homerun or when he first learned to ride a two-wheeler.

If I could only turn back the hands of time, he thought sadly.

When Nate finally got off the horse after two more rides, he and his grandfather dined on hot dogs—Nate's with cheese and ketchup and Norris's with chili sauce and onions. Then they washed them down with Cokes, and Norris bought them both an ice cream cone for dessert.

"I still owe you a cotton candy," he promised his grandson. "We'll get it later while we're watching the show."

They walked along the midway for another twenty minutes, and Norris bought the little boy a battery-operated flashing circus light. Then a whistle sounded, and people headed toward the opening in the large blue-and-white-striped tent. As Norris neared the big top, he again began to experience the peculiar fluttering in his chest.

Please, God, he prayed silently, don't let anything happen now. I don't want to spoil Nate's day at the circus.

Thankfully, the uncomfortable and disturbing sensation again passed. Norris and Nate entered the tent and found two empty seats in the fourth row, directly in front of the center ring.

"These look like good seats," Norris declared. "We ought to be able to see everything from here."

After everyone was seated, the overhead lights dimmed, and all the circus performers paraded around the oval track that encircled the three performance rings. Nate's eyes opened wide as he ogled the wondrous sights. There were men on stilts, jugglers, fire eaters, clowns, trained chimpanzees, circus horses, caged lions and tigers and—bringing up the rear—a pair of elephants.

When the parade came to an end, the ringmaster introduced the first acts of the evening: three troupes of acrobats and jugglers, one troupe performing in each of the rings.

"Why are there three different shows?" Nate complained. "I can't watch them all at one time."

"Then just pay attention to what's going on in the middle ring."

"But I don't want to miss anything."

"I don't blame you," his grandfather replied with a smile. "I guess life is too short to concentrate on the center ring and ignore what is happening in the other two."

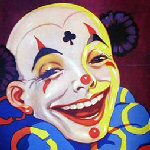

The acrobats and jugglers concluded their performance, bowed and ran toward the exit in the tent that led to their mobile dressing rooms. While the grounds crew set up the equipment for the next act, a dozen brightly clad clowns entered the center ring to entertain the audience with their hilarious antics. Nate clapped his hands to show appreciation of their zany humor.

Norris was laughing at an exceptionally short clown riding a ten-foot-high unicycle when he saw a very unusual clown standing silently and motionlessly near the main entrance. Unlike the other clowns whose costumes were decorated with garish stripes and polka dots in vibrant shades of red, yellow, blue, orange and green, the somber, motionless clown was dressed all in black. His face was white, but he had no bulbous red nose, no brightly colored wig and no exaggerated smile painted on his mouth.

Norris found the sight of the dark clown quite eerie. He predicted that more than one child would have bad dreams about killer clowns when they went to sleep that night. He wanted to look away, to watch the other clowns cavorting in the center ring, but he was unable to do so. Mesmerized by the gloomy clown, his gaze never faltered. Neither did the clown's. The black, emotionless eyes seemed to hold the old man's.

A vague image suddenly flickered in his memory, and Norris was frightened.

I've seen that clown somewhere before, he thought, but I don't know where because I've never been to a circus.

The ringmaster walked into the center ring, blew his whistle and announced the next acts, equestrians, as the frolicking clowns scampered out the exit—all, that is, except for the macabre clown dressed in black who stood still as a statue, silently staring at Norris Goddard.

While Nate watched the attractive young women in sequined leotards ride on the backs of trained horses, his grandfather sat speechless beside him, heart pounding with terror, as he slowly began to recall early childhood memories buried deep in his subconscious.

The blue-and-white-striped tent of the Gunther Brothers Circus seemed to drastically shrink in size, and the temperature within the tent rose to an unbearably high level. Norris began to perspire. There was a ringing in his ears, and he feared he might pass out. He closed his eyes to fight the nausea and loosened the top buttons of his shirt in an attempt to cool off.

When he opened his eyes again, his surroundings had changed. He saw with horror that he was still in a circus big top, but this one was much larger. The people in the audience—mostly mothers and children—seemed to be taken directly from a page of history. From their clothing and hairstyles, Norris assumed the time was the early 1940s. Was it all in his mind, or had he somehow managed to turn back the hands of time, as he had wished to do earlier that evening?

Feminine laughter from the seat beside him made Norris turn suddenly. In Nate's wooden chair sat a pretty young woman with red hair, green eyes and a fair, freckled complexion.

"Mother," he moaned quietly when he recognized his dead parent from the old photographs he had seen.

The excruciatingly painful memories his young mind had successfully suppressed more than sixty years earlier suddenly resurfaced to torture him. It had been July 6, 1944. His father had been at work in a nearby defense plant the afternoon the Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus performed in Hartford, Connecticut, so Norris was in attendance with only his mother.

Tears fell from Norris's eyes as he relived the tragic events of that awful day. There were nearly seven thousand people crowded under the circus big top, which had unfortunately been waterproofed—as was common practice at the time—with a highly combustible mixture of paraffin and gasoline. A fire broke out, and the flames rapidly climbed up the canvas walls of the tent and then quickly spread along the top. The frightened spectators in the audience ran for the main exit as the fire traveled above them, but in their panic to escape the menacing fire they ran directly toward the part of the tent that was being consumed by flames. The tragedy was further compounded by a wild animal chute that was blocking one of the other exits.

The big top was a virtual inferno. The tent poles soon collapsed, and the burning remnants of the roof caved in. In a matter of only six minutes, the tent had been completely destroyed. All that remained of the once colorful circus tent filled with happy faces were burned bodies and the smoldering ashes of the big top. One hundred and sixty-eight victims—mostly children—lost their lives in the fire, and hundreds of others were injured.

Yet Norris was ignorant of the exact details concerning the fire and was unaware of the body count. All he knew was that in the stampede for the exit, he had been separated from his parent. One of the high wire artists had grabbed him and heroically carried him to safety. The brave man then left the shaken boy with a group of survivors as he tried to give aid to the injured.

Young Norris, his face blackened and his eyes burning from the acrid smoke, cried for his mother. Yet despite his pitiful wails, Geraldine, the Irish woman with the red hair, green eyes and freckled face did not respond. Instead, it was a melancholy clown dressed all in black who comforted the child. The clown never spoke to him, but the man's white-painted face and dark piercing eyes held compassion and profound sympathy. Later, when Norris's father arrived at the scene to identify his wife's remains and take his son home, the clown quietly disappeared into the crowd.

Eventually, the images from the past faded, and the horrific memories subsided—although they would never completely desert him as they had in the past. Norris looked around. His beautiful mother and the other men, women and children from 1944 were gone. Beside him once again sat his grandson, watching with rapt attention three rings of trapeze artists. The grandfather smiled and tousled the boy's hair affectionately.

The fluttering in his chest—much sharper and stronger than before—temporarily took Norris Goddard's breath away. He was convinced he was going to die, and he wanted desperately to get in touch with his son before he did. The old man reached into his pocket and took out his cell phone, but he discovered that the battery was dead. He would have to use the pay phone in the gas station across the street.

"Come outside with me for a few minutes," he told his grandson.

"But I want to see the trapeze act."

"It's important, Nate. I have to call your father. I'm not feeling well, and I don't want to risk driving home—not with you in the car."

The child was reluctant to leave the circus, but he knew his grandfather would not make such a request lightly.

As Norris was crossing the street, protectively holding on to his grandson's hand, a small private airplane flew overhead at an elevation much lower than planes usually flew in that area. The engine sputtered and abruptly died.

"Oh, my God!" Norris cried as he picked up Nate and began to run for cover.

The two then watched in horror as the plane crashed into the big top of the Gunther Brothers Circus and exploded on impact.

* * *

Pandemonium reigned. Sirens blared, people screamed and children cried. The smell of smoke and death hung in the air. Norris stood outside the convenience store, watching events unfold that were so similar to those he'd lived through a lifetime ago.

An hour later, Fordham and his wife made their way through the crowd. The worried parents cried with relief when they saw that their son had not been killed or injured. Carol Anne sobbed with joy as she tightly hugged her little boy.

"When we heard about the crash, we were beside ourselves," she cried.

"We're okay," Norris assured his daughter-in-law. "We got out of the big top before the plane went down. We were crossing the street when it struck."

"I missed the end of the trapeze act," Nate told his mother. "Grandpa wasn't feeling good, so he wanted to come over here and make a phone call."

"What's wrong?" Fordham asked with concern.

"Nothing, I'm fine now. It must have been indigestion. You were right about the junk food. Those two chili dogs really did a number on me."

Norris didn't tell his son about the terrible recollections he'd had that night. Those memories—painful though they were—were his, and he would take them to his grave.

* * *

When the flames were extinguished and the fire engines left the scene, the surviving circus patrons were allowed to retrieve their cars from the field next to the old Madison Drive-in. Fordham and Carol Anne had long ago taken their son home, but Norris had insisted on waiting for his car.

The field was dark, and the old man, one of the few survivors of the inferno, was alone. As he took the keys out of his jacket pocket and unlocked the car door, he wondered sadly how many cars had lost their owners that night to the deadly blaze. He started the engine, drove down the field to the road and turned his head to the right to make sure no cars were coming from that direction.

Standing outside looking in through the vehicle's passenger window was the silent clown dressed in black. The dark eyes that stared at the old man seemed as though they had seen centuries of sorrow and tragedy, but Norris was no longer frightened by the mysterious apparition. Instinctively, he knew that he owed his life to it.

"Thank you," he mouthed through the glass of the closed window. "Again."

The dark clown smiled ever so slightly and then vanished into the night.

I always knew that underneath that haughty exterior Salem was nothing more than a clown!