Miracle at St. Boniface's

Almost two decades before author William Peter Blatty wrote his bestselling, controversial novel The Exorcist, a family in a small Pennsylvania community not far from Pittsburg nearly lost their thirteen-year-old son to the legions of hell.

Young Stephen Kirkpatrick was no different from other adolescent boys of his day. He attended the local Catholic school three seasons of the year; and in the summer, when he finished his chores, he played Little League baseball and watched Superman and The Lone Ranger on television. There was nothing in his childhood that would lead one to suspect the horror that was to come.

Then one afternoon, late in the month of September, Stephen came home from school and, as usual, went into his bedroom to do his homework. Twenty minutes later Verna Kirkpatrick heard a blood-curdling shriek coming from his bedroom. The terrified mother dropped her sewing and ran to check on her son.

The temperature in the boy's bedroom had fallen to below zero, and frost had formed on the inside of the window panes. When she saw her son, barely conscious, suspended in midair above his bed, Verna screamed. Annoyed by the disturbance, Stephen glared down at her, his eyes burning with hatred, and cursed his mother in a low, guttural voice that sounded more like an animal growl than human speech. Verna was so shocked by the foul language he used that she ran from the room, but even through the closed door, she could hear the boy's profane tirade continue. The filth that came from his mouth would have made a sailor blush. She could not imagine her son knowing such language, much less using it. Fighting back her tears, Verna ran downstairs to the kitchen where she telephoned both her husband and Father Kiernan O'Rourke, the family priest.

Randall Kirkpatrick, like most fathers of his generation, believed a good spanking would solve all discipline problems. When his hysterical wife phoned him at work and told him that Stephen was in his room swearing uncontrollably, Randall clocked out early and drove home. As he walked upstairs to the boy's room, he was prepared to administer a few sound smacks to his son's derrière, but when he opened the bedroom door and saw Stephen lying on the ceiling, foaming at the mouth, all his 1950s parenting skills vanished.

His son's sudden use of profanity shocked Randall more than it had shocked his wife, but he did not run from the room as Verna had. Instead, he bravely tried to get hold of the situation.

"Get down from there this instant!" he ordered sternly.

Stephen's eyeballs rolled back so that the irises were no longer visible. Seconds later the lamp on the dresser flew across the room toward Randall's head. The startled father ducked just in time.

* * *

The parents, faced with a situation beyond their control, stared at each other helplessly.

"How did he get on the ceiling?" Randall asked his wife, expecting her to explain their son's bizarre actions.

Even if the poor woman had an inkling of what was wrong with the boy, she was spared the need to answer when Father O'Rourke arrived at the house.

"Oh, Father!" Verna cried, eager to relinquish responsibility to the Holy Church. "Thank God you're here!"

"What's wrong?" the priest asked, aware only that the child was in need of his help. "Is Stephen sick?"

"We're not sure what's wrong with him," Randall admitted. "We're hoping you can tell us."

When Randall opened the door to his son's bedroom, the parents and family priest stood agape, stunned by the sight of a thirteen-year-old boy tap-dancing across the ceiling. At the sound of his mother's startled cry, Stephen turned and laughed heartily at the sight of the open-mouthed priest.

"Top of the mornin' to you, Father," the teenager said with a brogue as genuine as though he had just stepped off a boat from Dublin.

The priest had no words. He simply crossed himself with one hand and grabbed his rosary with the other.

"What's that you say, Father? Oh! You're praying, I see."

Stephen proceeded to recite the Lord's Prayer both forward and backward, first in Latin and then in Aramaic. The boy ended his recitation with several choice insults directed toward Father O'Rourke, including calling him a name that suggested the priest had carnal knowledge of his own mother.

Verna gasped.

"Oh, Father! I don't know where he learned such language—certainly not in this house!"

The priest, pale and shaking, told the parents he wanted to speak to them downstairs.

"Leaving so soon, are you, Father?" Stephen mercilessly taunted him. "Why don't you stay awhile? I was just about to serve communal wine on the rocks and Eucharist with peanut butter and jelly, but I suppose you have a date with an altar boy. Well, don't let me keep you."

* * *

"That's not your son upstairs," Father O'Rourke said solemnly.

The boy's mother and father stared at the priest, not comprehending his statement.

"What I mean to say is that your son is possessed."

"Is that serious?" Verna asked innocently.

"A demon has taken possession of his body. We will have to appeal to the Church to send an exorcist to help him."

In 1954 the word exorcism was not part of the average American's vocabulary. The parents assumed, therefore, that an exorcist was a type of doctor.

"I hope Blue Cross/Blue Shield covers his services," Randall whispered in his wife's ear.

During the next several days, a succession of priests, bishops and even a monsignor tread up the stairs of the Kirkpatrick's Pennsylvania home to see the boy and decide for themselves whether or not they were faced with an authentic case of possession. The verdict was that demonic forces were at work, and the diocese reluctantly granted its approval for an exorcism.

Father Anatole D'aubigne, an elderly, extremely devout priest, was one of the few men in the modern Catholic Church who knew the ritual of exorcism. Many of his fellow priests laughingly referred to him as a witch doctor behind his back; and when in his company, they often treated him with condescension. It was the twentieth century, they reasoned, and even an institution as steeped in medieval customs and beliefs as the Catholic Church viewed demonic possession as little more than superstition. Father Anatole not only believed in Satan, but he also believed that the Dark One and his unholy army walked among men, endangering mortal souls with their every step. When he arrived at the Kirkpatrick home, it was with a profound belief in the boy's possession and in his own ability—with God's help—to drive the demon from him.

For five days and nights, the old priest prayed over the afflicted child, taking only quick meals and short naps to maintain his strength. All the while he prayed over Stephen, Father D'aubigne was subjected to the foulest verbal insults and sometimes actual physical abuse at the hands of the thirteen-year-old. Still, the old man's faith prevailed. On the sixth day, Stephen was at last free of the hellish entity that had tortured him.

After the evil spirit was driven out, a weary Father D'aubigne went downstairs to share the good news with the boy's parents.

"The demon has finally fled your son's body," he announced with exhausted relief.

"God bless you, Father!" Verna cried.

"There's no need to thank me," Anatole assured the grateful mother. "I am but God's servant in all matters. If you want to express your gratitude, take your son to church and offer thanks to the Holy Father. But first, you might want to feed him. His soul is safe, now you must care for his body."

* * *

Stephen Kirkpatrick remembered little of what transpired in the preceding weeks, and what he could recall was hazy, like when the dentist had given him gas to pull his tooth.

"Don't worry about anything," his mother told him whenever he questioned her about the cause of his nightmare-like state. "You're all better now. Father Anatole exercised you."

It was not until many years later that the boy realized the old priest had not cured him by having run him through a regimen of calisthenics.

Two days after the expulsion of the demon, both Father D'aubigne and Father O'Rourke made a personal visit to the Kirkpatrick home, anxious to see if the boy suffered any residual effects of the possession.

"How are you feeling today?" Father D'aubigne asked.

"I'm really tired," Stephen replied. "Must be from all those exercises."

The old priest smiled. Then he reached into his pocket and took out a very old crucifix, one that had been smuggled out of England by an escaping nun during the time of the Reformation.

"I'd like you to have this," the exorcist said, as he fastened the chain around Stephen's neck.

"But men don't wear jewelry," the boy protested respectfully.

"I do," Father Anatole said with a saintly smile. "And so does Father Kiernan. A crucifix isn't a necklace worn for its beauty but rather a shield worn for its power."

"It has power?" the boy asked, his eyes wide with fascination.

"Yes, my son. The power of God."

From that day on, the Kirkpatricks noticed a marked change in their son. He was no longer interested in baseball or fishing, and he no longer idolized Superman and the Lone Ranger. Instead, Stephen's new heroes were the Father, Son and Holy Ghost.

* * *

The Sixties brought about great social change in America. The innocence of the Fifties disappeared along with the Superman and The Lone Ranger television programs. Yet while many of the country's young men and women were protesting the war in Vietnam, attending rock festivals, having sex or taking drugs, Stephen Kirkpatrick—now in his twenties—joined the priesthood.

After being ordained, young Father Stephen said goodbye to his parents, left Pennsylvania and went to Massachusetts where he was assigned by the Archdiocese of Boston to St. Boniface's Church. Although Catholics were in the minority in the small New England town of Canterbury, Father Stephen loved his new home nonetheless. There was peaceful simplicity in life beside the sea, and the people of Canterbury clung to their Colonial Era and Early American history and to the ideals and dreams of generations gone by.

St. Boniface's, although the only church built after the Civil War, was still over a hundred years old. When Father Stephen first walked through the solid oak double doors, he was captivated by the beauty of the interior, particularly by the life-size statues of Christ and the Virgin Mary that stood at opposite corners near the front of the building.

Father Stephen was so proud to be assigned to the wonderful old church that he knelt before the Holy Mother, lit a candle and fervently prayed that he would be a good shepherd to his new flock. After close to ten minutes on his knees with his head bent in prayer, the young priest lifted his eyes and looked into the plaster face of the Virgin Mary. In her eyes, he saw tears.

At first Father Stephen did not believe the miracle of the crying Virgin. He assumed there must be a logical reason for the water on the statue's face. However, that Sunday when the priest gave his first sermon, dozens of parishioners saw not only the Virgin Mary weep, but they also saw drops of blood fall from the crown of thorns on Christ's head.

The tale of the miracle spread through Canterbury, and the following Sunday when the tears and blood reappeared on the statues, the media got wind of the phenomena. Soon people around the world were reading about St. Boniface's. Many people viewed the miracle with skepticism, and those who did not derived various messages from it. Left-wingers claimed it was a sign from God that the U.S. should pull out of Southeast Asia; right-wingers saw it as a warning against the breakdown of family values and the deterioration of the morality of the youth of America. Catholics, of course, saw it as an affirmation of their faith. The official position of the Church, however, would not be announced until a full investigation was conducted. To accomplish this, the Archdiocese sought the advice of the Vatican.

* * *

"I'm Father Giovanni Benedetto from Rome," the Vatican representative introduced himself to Father Stephen. "I've come to investigate the reports of a miracle at your church."

The young priest warmly welcomed his esteemed visitor.

"I've never seen anything like it," Father Stephen confessed with excitement and barely concealed pride. "Canterbury is a predominantly Protestant community, as you've probably been told. In all the years that St. Boniface's has been here, the church has never been more than half full. Now we have people standing in the aisles at every service. Of course, I realize many are simply curious, but if I can reach just a handful of them and bring them to the Mother Church, then it will all be worth it."

Father Giovanni, who had been staring intently at his fellow priest, asked quietly, "What will be worth it? You must be honest with me. Have you done something to create this miracle?"

"Certainly not! This is no hoax."

"No, I don't believe you're a dishonest man," the Vatican's representative announced. "Why don't you and I go out and have a cup of coffee or perhaps something to eat? I passed by a diner a few blocks down the street."

"Don't you want to see the statues of Mary and Christ first?"

"I'll have a look at them later. What I want to do now is talk to you. Come on, let's take a walk, and I'll buy you a cup of coffee."

Father Stephen was perplexed. Why had Father Giovanni traveled all the way from Rome and not bothered to even look at the statues?

As the two men walked to the diner, Father Giovanni commented on the beautiful architecture of the small Massachusetts town.

"Were you born near here?" he asked the young priest.

This question led to a series of seemingly innocent inquiries about Father Stephen's childhood. It was while the two men were sitting near a window at the diner, looking at the blue Atlantic in the distance, that Father Giovanni's questions shifted to more personal subjects.

"Did you have a lot of friends when you were a boy?"

Father Stephen stopped sipping his coffee, his cup pausing midway between the table and his mouth.

Are all Italians this nosey? he wondered.

"Not a lot," he replied politely. "But I did have a few close friends."

"Do you stay in touch with any of them?"

"Not really."

Stephen began to feel uncomfortable.

"How was your flight from Rome?" he asked, wanting to change the subject.

The older priest gave a monosyllabic answer and continued to question him.

"Why haven't you kept in touch with these friends?"

"When I was thirteen, I was quite sick for several weeks, and my friends and I drifted apart."

Father Giovanni's eyes narrowed.

"You were sick? What was wrong with you?"

Father Stephen had reached the limit of his patience.

"Look, Father, I don't mean to be rude, but I don't see that my childhood illness is any of your concern. You're here to investigate the miracle, not me."

"All right. Let's go back to the church, and you can show me your miraculous statues."

* * *

"The first time I saw the tears on the Virgin Mary's face," Stephen explained, "was when I knelt here, lit a candle and prayed."

"That was your first day at this church, wasn't it?" Father Giovanni asked, making it sound like a police interrogation.

"Yes."

"And, quite naturally, you were anxious to be a good priest, were you not? I mean you were newly ordained and you wanted to be a success in your chosen field."

Father Stephen began to feel ill at ease again. What was the older man's obsession with asking personal questions?

"And here is our statue of Christ," he said, trying to distract the Italian.

As Father Stephen described in glowing detail the blood on the Savior's brow, Father Giovanni watched him intently.

"Don't you want to examine the statues or take some photographs to document the case for the Vatican?"

"That's not necessary."

The Vatican priest reached into his pocket, took out a pack of cigarettes and offered one to Father Stephen.

"No thanks. I don't smoke."

"Mind if I do?" Father Giovanni asked and lit one for himself.

But the Vatican priest did not inhale; in fact, he seemed to be quite content to simply hold the lit cigarette between his fingers, as though it was only something to occupy his hands.

"I quit smoking fifteen years ago," he confessed. "But every once and a while I like to light one up. It's the memories I guess. I suppose some of the younger priests feel the same way about women."

The Italian silently examined the statue, but it was a purely cursory examination.

Again, Father Giovanni turned his attention to the young priest from Pennsylvania and asked, "What about you? Do you miss women?"

"No, not particularly."

The Italian laughed.

"Oh, be honest. You must miss having sex. It's only natural."

A loud crash from the altar temporarily distracted Father Giovanni. A crucifix had fallen from its place of honor in a niche to the right of the altar. A faint smile appeared at the corner of the priest's mouth, and he continued asking questions.

"Didn't you like sex before you became a priest? Or were you not attracted to women?"

A large bible suddenly flew off the lectern. Father Stephen nervously spun toward the altar.

"What's going on?" he cried.

The older priest ignored the unusual disturbances around him.

"You never had sex, did you?"

"Why are you asking me all these questions? What has my personal life to do with anything?"

"Do you know what a poltergeist is, Stephen?"

"A ghost or maybe an evil spirit. I don't know."

"It's funny how in all documented cases of poltergeist activity there is always an adolescent involved."

"What are you talking about?"

When the young priest cried out in anger, one of St. Boniface's beautiful stained glass windows shattered into a thousand pieces.

"Poltergeists and demonic possession: the two have many things in common."

Father Stephen's eyes burned with fury.

"You think I'm causing all this, don't you? You believe I'm possessed again."

"I'm a psychiatrist, Father. I don't believe in possession," the Vatican's representative admitted. "But I do think a young boy entering puberty—especially one brought up in the strict environment of a Catholic school—has a great many repressed sexual desires to deal with."

Father Stephen shook his head, adamantly denying the other man's implied accusations. Meanwhile, the statue of the Holy Mother began to weep.

"You said you were sick when you were thirteen," Father Giovanni continued.

"Well, you obviously know the truth, so why should I deny it? I wasn't sick. I was possessed by a demon, but an exorcism saved me."

"No. You were correct the first time. You were sick, but the sickness ...."

A wind of hurricane force blew open the doors and down the aisle of the church, sending bibles and hymnals somersaulting in the air above the pews. Father Giovanni had to shout to be heard above the commotion.

"... but the sickness wasn't in your body. It ...."

Father Stephen erupted with a string of vile profanities that he had not uttered since he was thirteen years old.

"The only demon was in your mind," Father Giovanni shouted, bravely risking the anger of the younger man. "And it wasn't exorcised by an ancient rite. It was buried deeper into your subconscious. It came out again when you arrived here at St. Boniface's. Only now your illness has taken the form of miracles."

Father Stephen laughed.

"How could I have made a statue cry or bleed with my mind, or how could I have created these disturbances at the church today? Which of us is the crazy one, Father?"

"Neither of us is insane. Puberty brings great changes not only in a person's body but also in his emotions. It is a time when some young men and women discover they have extraordinary powers such as telepathy, clairvoyance and, in rare cases, telekinesis."

"Have you been reading Edgar Allan Poe? You really should stick to the scriptures rather than delve into the world of the supernatural."

"The Bible tells us of many strange events that, if they were to happen in our time, might be construed as supernatural in origin. Christ could walk on water, make the blind see, heal the sick and even raise the dead."

"Christ was the son of God," Father Stephen protested.

"As are you. Aren't we all God's children?"

"That's blasphemy!"

"When I was fourteen, I discovered I could see things others couldn't," Father Giovanni confessed. "I knew things others didn't."

"Maybe you're the cause of these miracles, then," Father Stephen said sarcastically.

"No. It wasn't a miracle. It was a gift. Some men are born with great intelligence, some with the ability to create beauty in art or music. We acknowledge these gifts; we understand them. But few people understand extrasensory perception or telekinesis, and the human race all too often fears what it doesn't understand."

Suddenly, all the extraordinary disturbances in the room ceased. The wind died down, and the Bibles and hymn books fell to the floor. The Virgin stopped weeping, and the blood ceased to flow from Christ's wounds.

"Does the Vatican know of your views on the subject of miracles?"

"The Vatican is not a single entity. It is an organization comprised of many men. Some men's minds are open; some remain closed. Do you want to know the difference between you and me, Stephen? I accepted my gift and gave thanks to God for bestowing it upon me. You obviously didn't see the hand of divine providence in your abilities. Your mind—already battling with hormonal changes, awakening sexual desires and ages-old taboos—could not deal with the added weight of a paranormal ability, so it invented a demon that could say or do anything it chose. It didn't have to live by the strict rules of your Catholic upbringing. Ironically, the so-called demon and the exorcism only served to reinforce the ideals you'd been taught. They were what drove you to the priesthood."

"And what about you? Why did you become a priest, given the fact that your beliefs are in stark contrast to the teachings of the Catholic faith?"

"In what way are they so different?"

"The Church teaches us that there are such things as miracles."

Father Stephen dramatically raised his hands, and in the center of his palms, there were bleeding lacerations.

"Stigmata," Father Giovanni said softly. "You share Christ's wounds. What an incredible mind you must have to go from demon to Savior in a few short years."

Suddenly Father Stephen's shoulders slumped, and he broke down under the emotional weight of his ordeal.

"I'm not a fake," he insisted. "I'm the real thing."

"Yes, you are. You are the miracle, not a couple of plaster statues that shed tears and drops of blood."

Father Giovanni let the young many cry. There were years of denial and repression that had to come to the surface. Finally, on the verge of complete mental and physical exhaustion, Father Stephen sat on the floor and looked up at the altar.

"You took away my faith," he announced with profound sadness.

"No, I didn't. Just look deeper. It's still there."

"I believed in the Church and its supremacy over the minions of hell. I believed that when Father Anatole cast the demon from me it was a sign from heaven."

"A sign of what?"

"That miracles happen and that God does exist."

"If you need a miracle to justify your faith in Him, then look here," Father Giovanni commanded as he held up the old crucifix Father D'aubigne had given Stephen after the exorcism.

The young priest looked at the thick gold cross but saw nothing except his own reflection in the gold.

"God created you," Father Giovanni said softly. "There's your miracle."

Father Stephen buried his head in his hands and wept.

"God help me," he cried. "I'm so confused. I don't know what to think, what to believe anymore!"

The quiet of the church was broken by the sound of the solid oak doors being opened and closed.

"Excuse me," a heavily accented voice spoke. "Are you Father Stephen Kirkpatrick?"

The young priest opened his eyes and saw an overweight, balding priest walking down the aisle toward him.

"Yes, I am," he replied. "Who are you?"

"I'm Father Giovanni Benedetto. I've come from Rome to investigate the alleged miracle at your church."

"What?" the young priest asked with confusion.

"The miracle. I want to see the statue that cries and the one that bleeds. I have been sent here by the Vatican to ascertain if the miracle is genuine. Didn't you get my telegram? I told you I'd be arriving today."

Father Stephen looked around the church. The man who had earlier claimed to be Father Giovanni was gone.

"Did you see someone leave as you came in?" he asked the portly priest.

"No. You were the only one here."

Father Stephen looked at the shattered stained glass window that had miraculously been restored. The angel it depicted looked amazingly like the young priest's recent visitor.

Meanwhile, the newly arrived Father Giovanni walked toward the statue of Mary in the corner of the church.

"Is this the statue that cries?"

He took a small camera out of his pocket, inserted a flash cube and photographed the Virgin from several angles.

"It looks like an ordinary statue to me. Are you sure that a miracle occurred here?"

"Yes, Father," Stephen replied with a smile, convinced his faith—like the stained glass window—had been fully restored. "There was most definitely a miracle here."

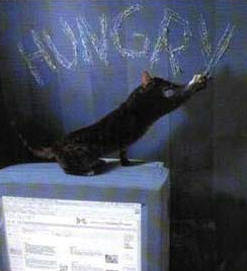

Miracles? It's a miracle I can get anything done around here with Salem as a pet!